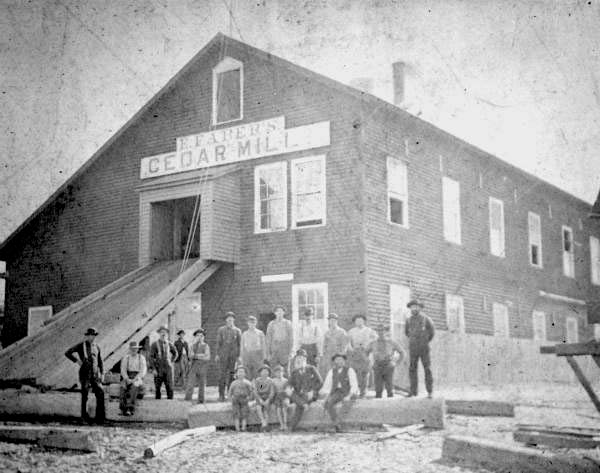

Levy County is located in north-central Florida. The county seat is Bronson. The county is named after David Levy Yulee, a planter and political leader in Florida during the 1800s. Levy County was created in 1845 by the Florida legislature from lands formerly occupied by the Seminole Indians. Levy County was a major center for pencil manufacturing in the United States from 1866 to the early 1900s, when all its coastal cedar trees had been sawed into pencil lumber.

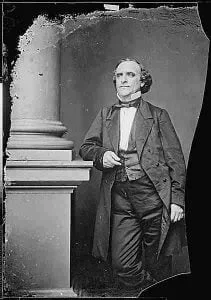

David Levy Yulee was one of the most prominent leaders of Florida after its ownership passed from Spain to the United States. In 1841 he was elected to represent the Territory of Florida in the United States House of Representatives. In 1845 he became the first person of Jewish ancestry to serve in the United States Senate. He continued in that position until 1861, when he was elected to serve in the Confederate States Senate. In 1842 Yulee began promotion, and was originally the majority owner, of the Florida Railroad, the state’s first railroad. At that time, the St. Johns River was impassible to sea craft. The railroad ran from Fernandina on Amelia Island to Cedar Key in Levy County on the Gulf of Mexico.

Evidence of an ancient indigenous culture that built shell mounds can be found along the Gulf Coast of Levy County. The shell mounds were concentrated between Cedar Key and the mouth of the Suwannee River. It is possible to canoe all the way to the Atlantic Coast from Cedar Key via the Suwannee River, Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River.

Cedar Key in Levy County was a major center of U. S. Army activity during the Second Seminole War. The headquarters of the Army of the South was on Atsena Otie Key, then known as Depot Key. There was also a prisoner of war camp on nearby Seahorse Key.

In the first week of January, 1923, the infamous Rosewood Massacre occurred in Levy County. Gangs of white supremacists attacked residents in the predominantly African-American community of Rosewood, after hearing rumors that a white woman in another town had been mugged by a drifter. Almost all of the houses in the community were burned. It is current estimated that at least 38 persons died at Rosewood. Approximately, 27 of those were innocent African-American men, women and children, while the Caucasian males were mostly killed while attacking the Carrier house in Rosewood.

Levy County is surrounded by five counties in Florida. Dixie County is located to the west. Gilchrist County forms its northern boundary, while Alachua County forms its northeastern boundary. Marion County is located to the east. The Suwannee River forms Levy County’s western boundary. Citrus County is located to the southeast.

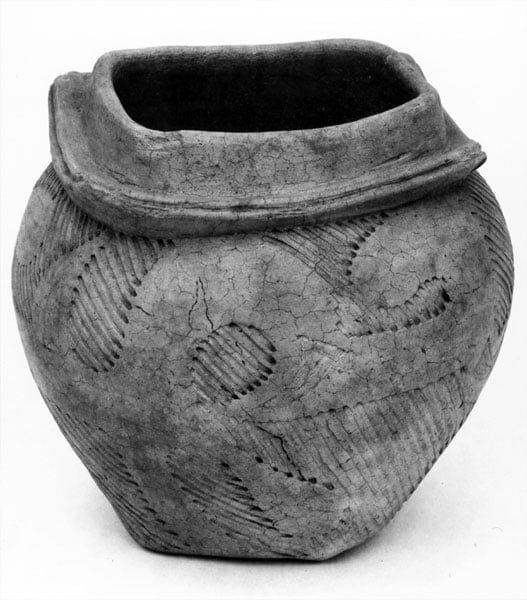

Cedar Key Mounds

Photo credit: Ebyabe

In 2012, a small portion of Cedar Key Mounds (Site 8LV42) was scientifically excavated by archaeologist, Kenneth Sassaman, 1 is a U-shaped ridge, composed mostly of oyster shells, measuring roughly 190 x 180 m (693 x 590 feet) in plan, and nearly 7 m (21 feet) tall. There is also an oval shell and sand mound at the mouth of the U, which is roughly 10 x 20 m (31 x 62 feet) in dimension.

In 1978 a section of the U-shaped shell mound was damaged by road construction. Not only did construction machinery cut across a section of the structure, but other shells were removed to use as paving. Poachers also have dug into the shells in search of artifacts. This archaeological zone is now within the Cedar Key National Wildlife Refuge and protected by the Federal government.

The remnant of a third mound, labeled 8LV41, is located about 600 feet to the northeast of the large U-shaped mound on a peninsula. It was severely damaged by archaeologist Clarence Moore at the turn of the century. Moore excavated hundreds of mounds in the Southeast, but was primarily interested in museum-quality Native American art and artifacts. The exceptional artifacts went into his private collection or were given to wealthy individuals, who helped fund Moore’s expeditions.

Most online and published references 2 see label this archaeological zone, the Cedar Creek Mound and state it was built by the “Timucua” Indians. There are multiple mounds and to date, no artifacts have been discovered that link the structure to a particular ethnicity. The various bands, who Florida anthropologists label Timucuans, probably arrived on the Atlantic Coast of Florida around 1150 AD. According to Sassaman, the site was abandoned no later than around 0 AD. The initial deposit of sand and shells occurred around 1500 BC. A large deposit occurred between 500-200 BC. Artifacts found in this layer were associated with the Deptford Culture. ((See section, this page, on Native American Cultural Periods.) The final deposit occurred around 200 BC-1000 AD.

Geology of Levy County Florida

Levy County is on the northern edge of the Mid-peninsula geological zone of Florida. The southern and western part of the county is in the Gulf Coast Lowlands. The eastern part of the county is in the Central Highlands Levy County is underlain by relatively young sedimentary rocks. Eocene limestone outcrops are common while Pleistocene Sand predominate the landscape.

All of Levy County drains into the Gulf of Mexico via the Suwannee, Wacassassa and Withlacoochee Rivers. Other major streams are the Wekiva River, Magee Branch, Tenmile Creek and Mule Creek. There several natural bodies of water in the county. They include Lake Rousseau, Long Pond, Chunky Pond, Rocky Hammock and Black Point Swamp. There is a band of tidal and freshwater marshes along the coast of Levy County.

- Withlacoochee is the Anglicization of the Muskogee Creek words ue rakkucce, which mean “river small.”

- Suwanee is the Anglicization of the Creek word for the Shawnee Indians, suwani.

- Waccasassa probably means “cattle range” in the Seminole dialect of the Creek language.

Native American Inhabitants

The land that is now Levy County was occupied by the Potano at the time of the Spanish conquest of Florida in the late 1500s and 1600s. It has been theorized that the Potano were part Maya, since Potan or Putan was a Maya ethnic group in the Yucatan Peninsula, that was heavily involved with trade in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Basin. The Spanish grouped all of the provinces in northeastern Florida and southwestern Georgia, speaking similar languages, into a province called Timucua.

No Native American people ever called themselves the Timucua. There was a province on Georgia’s Altamaha River named the Tamakoa – which is hybrid Totonac-Arawak for Trade People. The Spanish evidently derived Timucua from Tamakoa. However, the Tamakoa were hostile to Spanish domination and eventually moved to northeastern Georgia on the headwaters of the Oconee River. After 1785 they moved westward and merged with the Creek Confederacy.

Native American Cultural Periods

Earliest Inhabitants of Levy County Florida

Archaeologists believe that humans have lived in Levy County for at least 13,000 years, perhaps much longer. Clovis and Folsom points, associated with Late Ice age big game hunters have been found in the Apalachicola River Valley and the vicinity of Tallahassee. During the Ice Age, herds of giant mammals roamed the river bottom lands, swamps and coastal marshes. The mastodons, saber tooth tigers, giant sloths and other massive mammals died out about 8,000 years ago.

Archaic Period: 8,000 BC – 1000 BC

After the climate warmed, animals and plants typical of today soon predominated in this region. Humans adapted to the changes and gradually became more sophisticated. They adopted seasonal migratory patterns that maximized access to food resources. Archaic hunters probably moved to locations along major rivers during the winter, where they could eat fish and fresh water mussels, if game was not plentiful.

During the late Archaic Period, a major trade route developed along the Apalachicola River that the Gulf of Mexico with the Appalachian Mountains. The Suwannee River probably was also an important trade route to connect the Florida Gulf Coast with Georgia’s Atlantic Coast. During this time, Native Americans began traveling long distances to trade and socialize. The period 5000 BC through 2000 BC in northern Florida has been labeled the Mount Taylor Culture by anthropologists.

During the Early Archaic Period, bands of indigenous peoples, who survived by hunting, fishing, gathering edible nuts, fruits & roots, plus harvesting fresh water mussels, established seasonal villages in Levy County. The habitation sites were concentrated along the Apalachicola, St. Marks Rivers, Suwannee River, plus major streams. Villagers seasonally migrated between locations within fixed territorial boundaries to take advantage of maximum food availability from natural sources. For example, they might camp near stands of nut trees during the early autumn.

Beginning around 3,500 BC, Southeastern Native Americans began to intentionally cultivate wild plants near village sites. Over the centuries, selective cultivation resulted in domestic plants that were genetically different than their wild cousins. As the productivity of indigenous crops increased, the indigenous people were able to remain longer at village sites, and therefore had fewer habitation locations.

By the Late Archaic Period, c. 2000 BC, the knowledge of making pottery had spread from the Savannah River Basin to the Apalachicola and St. Marks River Basins. Large mounds of freshwater mussel shells developed along the Apalachicola at locations where villagers camped for generation after generation. More sedentary lifestyles made possible the development of pottery and grind stones. These items were impractical as long as people were migratory.

Woodland Period (1000 BC – 900 AD)

Beginning in the Woodland Period Native population began concentrating along mouth of the Apalachicola, Aucilla, St. Marks, Ecofina and Suwannee Rivers. A sedentary lifestyle was made possible by abundant natural food sources such as game, freshwater mussels and Live Oak acorns and the cultivation of gardens. Agriculture came very early here. Initially, the cultivated plants were of indigenous origin and included a native squash, native sweet potato, sunflowers, Jerusalem artichoke, amaranth, sumpweed, and chenopodium. This proto-agricultural society is known as the Deptford Culture.

The early villages were relatively small and dispersed. There was probably much socialization among these villages because of the need to find spouses that were not closely related. Houses were round and built out of saplings, river cane and thatch.

The Woodland Period peoples of the region built numerous, low mounds. Apparently, most mounds were primarily for burials, but may have also supported simple structures that were used for rituals or meetings. They were constructed accretionally. This means that the mounds grew in size over the generations by piling soil and detritus from the village over recent burials. Whereas Native American farmers generally held all mounds to be sacred, 19th century Florida farmers often plowed through the smaller ones or even intentionally leveled large mounds. As a result, few Woodland Period mounds are visible on the surface of Levy County, even though dozens or even hundreds once existed.

Native American villages in the region around Levy County were associated with the Swift Creek Culture and later, the Weeden Island Culture. In Levy County, the Middle Woodland village sites are typically located at the edge of the flood plain of rivers and major creeks. The Yon Mound Site in Bristol County was originally inhabited between around 0 – 350 AD. A large town with mounds was established there around 1200 AD that remained occupied till about 1550 AD.

The Swift Creek Culture evolved into the Weeden Island Culture around 300 AD. The Weeden Island Culture is distinguished by the construction of large ceremonial centers and the creation of sophisticated, sometimes exotic, ceramics. The two largest Weeden Island Culture sites near Levy County were Kolomoki in southwest Georgia and Letchworth Mounds near Montecello, FL. Inhabitants of Levy County tended to produce artifacts reflecting many ceramic traditions. Pottery shards from several distinct styles in the Gulf Coast s have been found in the vicinity of Levy County.

Coinciding with the disappearance of Swift Creek villages is the wide spread use of the bow and arrow.This next cultural phase is known as the Alachua and Suwannee Valley Cultures. Arrow points are easily distinguishable from atlatl (javelin) and spear points by their smaller size. It is not clear if the scarcity of Late Woodland settlement equates to a drop in total population. The efficiency of hunting with a bow may have made dispersed hamlets more desirable than concentrated villages.

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (900 AD – 1645 AD)

Stark cultural changes began appearing on the Apalachicola River around 800 AD. Within a century they also appeared on the Chattahoochee and Ocmulgee Rivers in Georgia, plus the Suwannee River in Georgia and Florida. The earliest mounds of this new cultural tradition in the river basin have been radiocarbon dated around 900 AD, but the initial cultural influences came a little earlier. During the late 800s and 900s AD, most Mayas cities collapsed due to an extended drought, famines and chronic warfare. Given that many Mesoamerican words and some Maya DNA can be found among contemporary Creek Indians, it is quite likely that the cultural change was sparked by the settlement of Maya commoner refugees along the Apalachicola. However, this theory has not been fully accepted by the archaeology profession.

In 1947, prior to the professional study of many Southeastern Native American sites, a congress of archaeologists, meeting at Harvard University, decided that the first mounds were built in Ohio and the first advance, agricultural society occurred at Cahokia Mounds, Illinois. The advanced culture was labeled the Mississippian Culture, because Cahokia was near the Mississippi River. It is now known that large ceremonial mounds were being constructed in the Southeast as early as 3500 BC (Watson Brake, LA) and that “Mississippian cultural traits” first appeared in southern Florida, then spread to the Apalachicola and Ocmulgee River Basins at least as early as 900 AD . . . 150 years before they appeared in full bloom at Cahokia. Therefore, the term, “Southeastern Ceremonial Complex” is a more accurate description of cultural history in eastern Florida.

Suwannee Valley Culture

The Okefenokee Swamp region of southern Georgia and northern Florida was territory of an advanced Native American culture about which little is known. There are 74 Native American mounds in the Okefenokee Swamp. The Oconee Creeks consider the Okefenokee Swamp to be their birthplace, but by the time of European Contact, most Oconee’s lived in northeastern Georgia. Their name means “born in water.” Native peoples with similar cultural traditions, during this period occupied villages along the Suwannee River from the Okefenokee Swamp, southwestward to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Native Peoples living in the region between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers were agricultural after around 1000 AD, but apparently did not build large towns or tall mounds as can be found farther north in Georgia. Florida anthropologists have identified evidence of a steady cultural development in the region between 900 AD and the 1500s when Spaniards arrived. However, the language of the indigenous peoples may have evolved due to influence from the Apalachee to the west and Arawaks to the east.

European Colonial Period

The archives from the earliest European expeditions and colonization efforts in Florida describe a very different ethnic landscape than observed by the waves of settlers who entered Florida in the early 1800s. The aboriginal peoples of Florida by that time had been brought to near extinction by diseases and Spanish oppression. The few survivors assimilated into the Muskogean culture of Native American immigrants from Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee.

There is archival and archaeological evidence that European diseases began to sweep through the Southeast as early as 1500 AD. A smallpox plague in the Yucatan spread across the Caribbean and then was carried to the Gulf Coast by Native American merchants.

In 1528 Spanish explorer, Panfilio Narvaez, passed through present day Levy County. Narvaez made no mention of any plagues in the interior of Florida, but did discuss abandonment of coastal villages in the Florida Panhandle.

In autumn of 1539, when the Hernando de Soto Expedition arrived in present day Leon County, the Native provinces were still thriving in the interior. Most seem to have not been affected by the diseases that were ravaging communities on the Gulf Coast. However, de Soto’s army left a path of feral pigs and human pathogens wherever it went. The Spaniards stayed in the town of Anhaica throughout the winter of 1539-1540. The impact of the pathogens they deposited among the Florida Apalachees was probably considerable.

Queen Anne’s War

In 1701, the War of Spanish Succession broke out in Europe. It pitted the Kingdom of France and the followers of Phillipe of Anjou against England/Scotland/Great Britain, the followers of Archduke Charles of the House of Hapsburg in Austria, the Netherlands, Austria, the Duchy of Savoy and Portugal. In 1702 the war spilled over into North America, where it was known as Queen Anne’s War.

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, commander of French forces in the Gulf of Mexico, urged the governor of Florida to arm the Apalachee in order to attack the British colonies. Spanish officials had always avoided the distribution of firearms to the Apalachee, fearing it would enhance the chances of an Apalachee revolt.

In 1701, the Spanish government in St. Augustine began planning an invasion of the British colony of Carolina through the lands of the Creek Indians in present day Georgia. The plan included giving some second-class weapons to Apalachee soldiers. In 1702 an Apalachicola-Creek army decisively defeated the Spanish near the confluence of the Chattahoochee and Flint Rivers. Approximately, ¾ of the Spanish soldiers were killed. This battle marked the end of any Spanish influence over the Apalachicola.

In 1702, the surviving Spanish soldiers began efforts to build a fort around the casa fuerte. Undoubtedly, as always, the Apalachee were forced to provide free labor for the construction. The fort was completed in 1703 despite a horrific epidemic, which killed many Apalachee people.

In 1704 and 1705 combined Apalachicola-Creek, Ochesee-Creek and British armies completely destroyed the mission system and forts of northern Florida. In 1704, the surviving Spanish soldiers had burned the fort at San Luis and retreated to St. Augustine. By 1707 Spanish occupation of northern Florida was pretty much limited to the fortified towns of St. Augustine and Pensacola.

Many surviving Apalachee fled northward into the future colony of Georgia and became associated with the embryonic Creek Confederacy. Maps of that era show a small Florida Apalachee province on the Upper Savannah River and a large Apalachee province in southeast Georgia. The province in southeast Georgia was probably also composed of refugees from Florida.

At the close of the Yamasee War (1715-1717) many towns that had been clustered around the Fall Line of the Ocmulgee River in central Georgia relocated to the Chattahoochee River. They were on both sides of the river, since no one told them that it would become the boundary between two states one day. Over time more Creek towns settled along this corridor. The Creeks gradually extended their territory southward along the Apalachicola River to the Gulf Coast. The Creek towns in southern Georgia began hunting in the Florida Panhandle. There was little that Spain could do since the area had essentially been abandoned. Shawnee towns that were allied with the Creeks, relocated to the Suwannee River Valley during this period.

After the American Revolution (1775-1783)

In the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolution, Spain re-acquired West and East Florida, which included the Florida Panhandle and all lands of present-day southern Alabama north to the 31st parallel. What is now Levy County returned to nominal Spanish sovereignty in East Florida, but Spain was too weak to have any significant influence over the Creek Confederacy, other than by bribery. The Creek Confederacy even built a fleet of gunboats for a navy to patrol the Apalachicola River and the coast.

The zenith of power for the Creek Confederacy was the period between 1783 and 1812. The Creeks controlled the largest territory of any Indian tribe in the United States. Unlike the Cherokees, they had not as a whole sided with the British. During these decades, Creek leaders successfully played the United States, the Spanish in West Florida and East Florida against each other.

Creek Indian followers of William (Billy) Augustus Bowles, self-declared “Director General of the State of Muskogee,” built a lighthouse or watchtower near Cedar Key in 1801. A unit of Spanish soldiers demolished the tower in 1802. At this time, the Creek Nation maintained its own gunboat navy. The Creek’s goal was to create a sovereign nation from their territories in Georgia, Alabama and Florida.

During the War of 1812, American armies invaded Spanish West Florida at will, in order to pursue bands of Red Stick Creeks. The Treaty of Fort Jackson that ended the Creek Civil War (Redstick War) severely punished non-Muskogee Creek towns in southwest Georgia, who had always been staunch allies of the United States. They were stripped of their lands. Rather than moving to Alabama, many Itsate (Hitchiti) Creek towns moved down into the Florida Panhandle. There were very few people of Spanish ancestry living in Western Florida at this time. Spanish officials seemed glad to have agricultural Indians in their midst, who were no longer allied with the United States.

First Seminole War (1814-1819)

Intermittent hostilities began in southwest Georgia around 1814 when settlers began to force out Itstate Creek towns, who were not members of the Muskogee-Creek Confederacy.. During the late 1700s and early 1800s the Creek towns in southern Georgia that were not members of the Creek Confederacy were labeled “Seminoles” on American maps. They did not at this time consider themselves anything but Creek Indians within a particular independent province. These towns did not sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, since at the time, they were allies of the United States, not defeated belligerents. They did not feel bound by the terms of the treaty.

The first round involved the garrison at Fort Scott in extreme southeast Georgia and a nearby Miccosukee village named Fowltown. American soldiers began using lands near the fort that had not been sold to the United States. This resulted in the Miccosukee successfully attacking a cargo boat headed for Fort Scott. Combined regular army and militia forces eventually defeated the Miccosukee. They moved southward into Spanish territory that would eventually include Levy County. Most Creek families almost immediately established prosperous farms, but some insisted on attempting live off of small gardens, hunting and fishing. These more conservative families generally did not thrive.

During the next three years, small bands of former Red Stick Creeks and Independent (Seminole) Creeks staged raids from bases in Gadsden and Liberty Counties into Georgia and Alabama. These guerilla actions were targeted at settlers who were in lands that the raiders felt had been stolen from them by the Treaty of Fort Jackson. It was not uncommon for African slaves to return back to Florida with the raiders. Georgia plantation owners were terrified that the Florida Creeks would eventually encourage a slave rebellion, because all Creeks had a long history of giving sanctuary to escaped slaves.

In 1818 an American army under General Andrew Jackson illegally invaded Spanish Florida to attack the Independent Creek towns and villages. Over half his army were Creek Indians from Georgia, who had been promised that they could stay in Georgia forever, if they volunteered to fight their Seminole brothers in Florida. A battle was fought near a natural bridge on the Ecofina River on April 14, 1818 in Taylor County. Jackson’s army then moved southwestward to Old Town on the Suwannee River. Many of the occupants fled after the initial assault. However, an Oconee mikko, Billy Bowlegs stood his ground for awhile with about 200 Oconee soldiers. They were soon driven back by the overwhelming force of Jackson’s army. Bowlegs then attempted to make another stand at place soon called Bowlegs point, but now is called the Jena community. Bowlegs and his surviving soldiers were captured later on at Big Rocky Creek.

Many Seminole-Creek farmsteads and villages were burned, but the Florida Creeks did not suffer severe casualties. The Florida Creeks were forced into forming a more permanent political alliance that became the Seminole Indians. Most Creek villages also shifted southeastward to be farther from U.S. Army forts. The army could not remain permanently in Spanish Florida, but its presence pressured Spain into negotiations for selling West Florida.

In 1818 negotiations were begun between Spain and the United States concerning the future of Florida. In 1821 Spain ceded what is now southern Alabama, plus Florida to the United States in return for the United States renouncing its claims on Texas.

Treaty of Moultrie Creek (1823)

In 1823 the United States negotiated with the Florida Creeks as a separate political entity that Americans called the Seminole Indians. Creek farmers in the region between the Apalachicola and Suwannee Rivers had become affluent from selling produce and livestock to South Georgia towns. The impoverished Georgia farmers on small tracts were jealous. They dreamed of becoming planters on the already improved Creek farmsteads.

The non-belligerent Creek farmers near the Georgia border were forced south along with the trouble-makers into a large reserve in central Florida. The Apalachicola Creeks were treated as a political entity separate from the other Creeks in Alabama and Florida. Henceforth, all other Creeks in Florida were known as Seminoles. Over the decades that followed, Americans elsewhere increasingly viewed them as an ethnic group separate from the Creek Indians. By the early 1900s, Seminoles were typically viewed as being indigenous to Florida.

The Treaties of Cusseta and Paynes Landing (1832)

In March of 1832, their situation had so weakened that Creek leaders in Alabama agreed to sign a treaty to relinquish their remaining lands. Federal, state and Creek officials met at the Creek town of Kawshite, (Cusseta in English) on the Georgia side of the Apalachicola, to force the Creeks to renounce sovereignty over their territory. Any Creek families wishing to stay in Alabama (but not Georgia) were granted 320 acres fee simple of land of their choosing. Those that agreed to migrate to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) were to be provided travel costs and sufficient supplies to survive the first year in their new home. The Federal government also paid the Creek Confederacy $350,000 to support Creek orphans.

Most Creek families did not know the boundaries of their farms, nor their values. Almost immediately after the Treaty of Cusseta was signed, real estate speculators began buying Creek farms for pittances. The Creek unfortunately assumed that they could just move somewhere else, as in the past. An even worse situation was caused by squatters, who merely seized Creek farmsteads by force. As before, the Alabama state government did nothing to protect Creek families, who were now state citizens. After becoming homeless, many Creek families drifted southward into Florida to find land that nobody claimed. These Creeks became the ancestors of most of the families, who now claim Creek heritage in northern Florida.

In May of 1832, shortly after the Treaty of Cusseta, Seminole leaders were summoned to a treaty conference where they were pressured to relocate from Florida to the new Creek Nation in the Indian Territory. A select group of leaders were transported to the Indian Territory to view their prospective new home. Government officials reported that all of the leaders had signed an agreement to relocate. However, when the Seminole leaders returned, most claimed that they did not sign the treaty or were forced to sign the treaty. In either case, all claimed that they only had authority to commit their own town to removal, not all towns and ethnic groups in the Seminole Reservation.

Billy Bowlegs signed the Treaty of Paynes Landing, but then refused to travel to the Indian Territory. He and his followers retreated into the heart of the Florida Peninsula.

Second Seminole War (1835-1842)

The Second Seminole War broke out in late 1835, when the United States began using troops to force Seminole villages into relocating to the Indian Territory. During the first year of the war, the U. S. Army suffered several horrific defeats. Small bands of Seminoles attacked remote farms and military units throughout much of Florida. They even destroyed the Cape Florida lighthouse near present day Miami.

In 1838, General Zachary Taylor took command of United States troops in Florida. His troops built five forts on the Econfina, Frenaholloway and Steinhatchee Rivers as a barrier to Seminole raiding parties entering the Florida Panhandle. They then built Fort No. 4 on Depot Key. This became the headquarters of the Army of the South. The facility included a dock, warehouse, fortification, civilian houses and hospital. On nearby Seahorse Key a prisoner-of-war camp and detention facility for Seminoles, who voluntarily submitted to being deported west, was established. This facility was named Catonment Morgan.

Colonel William J. Worth had declared that the Seminole War was over in August 1842. On October 4, 1842, a massive hurricane, producing a 27 feet high storm surge, struck Cedar Key and Seahorse Key. Cantonment Morgan was destroyed, while the Army headquarters complex suffered severe damage. Several Seminole leaders were at Depot Key to negotiate a surrender treaty, when the hurricane struck. After experiencing the hurricane, they refused to return there and returned to the Everglades. Those holdouts became the core of the Seminole Tribe of Florida. U.S. Army facilities on Depot and Seahorse Keys were abandoned after the hurricane.

Third Seminole War

The Third Seminole War was fought entirely in central Florida. Federal soldiers and surveying teams intentionally vandalized the orchards and villages of Billy Bowlegs followers. Bowlegs soldiers initiated a guerilla war against isolated white farmsteads. Eventually, Bowlegs and his men were bribed with large sums of money to relocate to the Indian Territory. Bowlegs carried $100,000 in hard cash and owned 50 African slaves, when he arrived in the Seminole Reserve in what is now Oklahoma. He soon became a wealthy cotton planter, whose lifestyle was little different than his white counterparts.

Citations:

- Director of the Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology, University of Florida[↩]

- See “McCarthy, Kevin M. Cedar Key, Florida: A History, p. 10. The History Press, 2007″ for an example.[↩]