By 1756 Colonel George Washington, commander of His Majesty’s Virginia Militia, was in a tough row to hoe. In 1754, a series of incompetent decisions that he made while on the journey back from delivering a diplomatic message to French-built Fort Duquesne, had triggered the French & Indian War in North America and the Seven Years War in Europe.

Beginning in 1754, at the start of this first global war, bands of Natives from the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes region devastated the frontier farmsteads in the Shenandoah Valley. If the war parties were led by Frenchmen, all adult males were killed, while generally women and children were marched west to be hostages, slaves or concubines. If no Frenchmen were around, all, regardless of age or gender, were usually killed. It was quite common for young adult captives to be burned alive. Toddlers either had their heads bashed against boulders or were hung from tree limbs, then shot with arrows. These acts strongly suggest a link to earlier practices of human sacrifice.

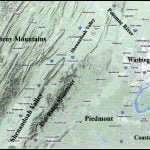

In 1755 Washington proposed that a large fort be constructed as a command center in the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley next to the crossroads hamlet of Winchester. It would link the British Army’s Fort Cumberland, MD with a chain of smaller forts farther south. Great Britain’s new commander in North America, John Campbell, Earl of Loudon, endorsed the idea. He never visited the fort, but it was named after him.

Virginia’s General Assembly and the House of Burgesses appropriated 1,000 British pounds for Fort Loudon’s construction. The fort was situated on a five-acre tract about 200 yards north of Winchester. Washington laid out a 204-square-foot fortification with bastions at each corner. Inside, he designed barracks for 450 men, a powder magazine, an officer’s guard house, a grand house and kitchen, and a drinking well drilled 103 feet through limestone. He designed a double timber palisade filled with dirt and stone. The bases of the fortification walls were 18 feet thick. Fort William Henry in upstate New York (of “Last of the Mohicans” fame) was very similar in size and construction.

As soon as excavation had begun on Fort Loudon’s buildings, what appeared to be a Native American cemetery was discovered. The burials were accompanied by artifacts that the English interpreted as being made by Indians. Washington reported to officials in Williamsburg that all the adult skeletons were much taller than those of Europeans, or the Indians in Virginia. Several were measured to be seven feet long, when a typical European male was 5’-6” at that time. There is no known record as to what became of the skeletons and artifacts in the cemetery.

In the 2 ½ centuries since that discovery of the 7 feet skeletons, Virginia’s historians have generally scoffed at the story. You will only hear it if you visit the Fort Loudon Museum in downtown Winchester. However, as most of the readers know, seven foot skeletons have been found in several ancestral Creek towns. It is quite common for Upper Creek males in the Southeast to be 6’-6” or taller. Male descendants of Eastern Muskogee and Itsate Creeks are typically around 6’-3”or taller. Early European explorers repeatedly recorded that the Muskogean men living in the Appalachians or Piedmont averaged about a foot taller than Europeans. The Fort Loudon skeletons are just one example among many of the enigmas associated with the Shenandoah Valley’s pre-European past.