Wood Working. The Yuchi men spend part of their time, when not engaged directly in procuring food, in manufacturing various useful articles out of wood. One form of knife, yanlibo’, ‘knife bent,’ used in whittling such objects, consists of a piece of iron curved at one after the fashion of a farrier’s knife (Fig. 15). The handle part of the metal is bound around with cloth or skin to soften it for the grasp. The wood worker draws the knife towards himself in carving. Thus are made ladles, spoons, and other objects that come in handy about the house. Larger objects of wood are shaped not only by whittling with knives, but by burning. For instance dugout canoes, tcu si’, were made of cypress trunks hollowed out in the center by means of fire. As the wood became charred it was scraped away so that the fire could attack a fresh surface, and so on until the necessary part was removed.

It sometimes falls to the lot of women to help in the manufacture of certain wooden objects. One such case is to be seen in the hollowing out of the cavity of the corn mortar. After the man has sectioned a hickory log of the proper length and diameter, about 30 by 14 inches, he turns the matter over to several women of his household. They start a fire on top of the log, which is stood up on end. The fire is intended to burn away the heart of the log, so, to control its advance and to keep it going, two women blow upon it through hollow canes. By pouring water on the edge the fire is kept within bounds and confined to the center. As the wood becomes charred it is scraped away, as usual, with the shells of fresh water mussels.

No decorative effects are produced in wood carving nor is it likely that any particular development in technique was reached by the carvers in former times.

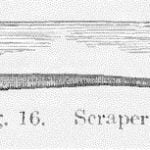

Preparing Hides and Sewing. – In preparing hides and skins for use the brains of animals are employed to soften and preserve them. Hides arc placed over a log, one end of which is held between the knees while the other rests on the ground, and are then scraped with a scraping implement to remove the hair. The scraper, tseame’satäné, for this purpose is a round piece of wood about twelve inches long with a piece of metal set in edgewise on one side, leaving room for a hand grip on each end (Fig. 16). This implement resembles the ordinary spokeshave more than anything else. A sharp edged stone is said to have taken the place of the iron blade in early times. Hides are finally thoroughly smoked until they are brown, and kneaded to make them soft and durable.

Sewing is done by piercing holes in the edges to be joined with an awl. Two methods of stitching are known, the simple running stitch and the overhand. The latter, on account of its strength, is, however, more commonly used. Sinew and deerskin thongs are employed for thread.

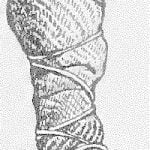

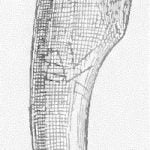

One specimen of awl, for sewing and basket making, consists of a piece of deer antler about six inches long into which a sharp pointed piece of metal is firmly inserted (Fig. 17). Bone is supposed to have been used for the point part before metal was obtainable. Several chevron-like scratches on the handle of this specimen are property marks.

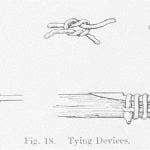

A few knots and tying devices observed in use and on specimens, are given in Fig. 18. Softened deerskin thongs were employed for tying and binding purposes.

Sheet Metal Work. The manufacture of German silver ornaments, such as finger rings, earrings, bracelets, arm bands, breast pendants, head bands and brooches, seems to have been, for a long time, one of the handicrafts practiced by the Yuchi men. This art has now almost passed away among them and fallen into the hands of their Shawnee neighbors. The objects mentioned in the list were made of what appears to be copper, brass and zinc alloy. The metal was obtained from the whites, and then fashioned into desired shapes by cutting, beating, bending, and punching in the cold state. The favorite method of ornamentation was to punch stars, circles, ovals, curves, scalloped lines, and crescents in the outer surface of the object. Sometimes the metal was punched completely through to produce an open-work effect. Several pieces of metal were sometimes fastened together by riveting. Ornamental effects were added to the edges of objects by trimming and scalloping. It is also common to see fluting near the borders of brace-lets and pendants. Judging from the technique in modern specimens, metal workers have shown considerable skill in working out their patterns. It is possible, moreover, that this art was practiced in prehistoric times with sheet copper for working material, in some cases possibly sheet gold, and that some of the ornaments, such as head bands, bracelets, arm bands and breast ornaments, were of native origin. Some of the ornamental metal objects will be described in connection with clothing.

Beadwork. Like many other Indian tribes the Yuchi adopted the practice of decorating parts of their clothing with glass beads which they obtained from the whites. Beadwork, however, never reached the development with them that it did in other regions. What there was of this practice was entirely in the hands of the women. There were two ways of using the beads for decoration. One of these was to sew them onto strips of cloth or leather, making embroidered designs in outline, or filling in the space enclosed by the outline to make a solidly covered surface. The other way was to string the beads on the warp threads while weaving a fabric, so that the design produced by arranging the colors would appear on both sides of the woven piece. For the warp and woof horse hair came to be much in use. Objects decorated in the first fashion were moccasins, legging flaps, breechcloth ends, garter bands, belt sashes and girdles, tobacco pouches and shoulder straps. The more complex woven beadwork was used chiefly for hair ornaments and neck-bands.

The designs which appear in beadwork upon these articles of clothing are mostly conventional and some are symbolical with various traditional interpretations. They will be described later. It should be observed here, however, that there is some reason to suspect that the beadwork of this tribe has been influenced by that of neighboring groups where beadwork is a matter of more prominence. The removal of the Yuchi and other southeastern tribes from their old homes in Georgia and Alabama to the West threw them into the range of foreign influence which must have modified some characteristics of their culture.

Stone Work. – Lastly we know, from the evidences of archeology, that at an early age the Yuchi, like the other Indians, were stone workers. All vestiges of this age, however, have passed beyond the recollection of the natives, so that nothing can be said first hand on the subject.