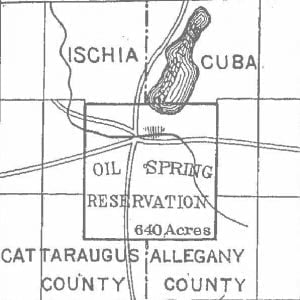

Wenrohronon Indians (Awěñro’roñ’non’, probably from a combination of the noun awěñ’rǎ’, the Huron form of the common Iroquoian vocable denoting ‘scum,’ ‘moss,’ ‘lather,’ with the verb stem –o’, ‘to float,’ ‘to be immersed or contained in liquid or in the earth,’ ‘to be in solution,’ ‘to be contained in,’ with the tribal appellative suffix –roñnon‘. Awěñ’ro’ (ouenro in the Jesuit Relations), the base of the term, signifies, as a geographic name, ‘where scum floats on the water’; hence Awenrohronon means ‘the people or tribe of the place of floating scum.’ The suggested meaning of the name would seem to indicate that the Wenrohronon may have lived in the vicinity of the famous oil spring of the town of Cuba, Allegany County, New York, described as a filthy, stagnant pool, about 20 ft in diameter, without an outlet. A yellowish-brown oil collects on its surface, and this was the source of the famous “Seneca oil,” formerly a popular local remedy for various ailments. The spring was so highly regarded by the Seneca that they always reserved it in their land-sale treaties). One of the tribes which, according to the Jesuit Relation for 1639, had been associated with the Neutral Nation and which had lived on the eastern borders of the Neutral Nation toward the Iroquois, the common enemy of all these tribes. As the territory of the Neutral Nation on the east side of Niagara river extended at this date south ward to the “end” of Lake Erie and eastward to the watershed of Genesee River, at least, the former habitat of the Wenrohronon must have been south of this territory.

So long as the Wenrohronon kept on good terms with the Neutral Nation they were able to withstand their enemies and to maintain themselves against the latter’s raids and incursions. But owing to some dissatisfaction, possibly fear of Iroquois displeasure, the Neutral Nation severed its relations with the devoted Wenrohronon, who were thus left a prey to their enemies. Deciding therefore to seek asylum and protection from some other tribe, they sent an embassy to the Hurons, who received them kindly and accepted their proposal, offering to assist them and to escort them with warriors in their migration. Nevertheless, the fatigue and hardships of the long retreat of more than 80 leagues by a body exceeding 600 persons, largely women and children, caused many to die on the way, and nearly all the remainder arrived at Ossossane and other Huron towns ill from the epidemic which was primarily the occasion of their flight. The Jesuit Relation cited says: “Wherever they were received, the best places in the cabins were assigned them, the granaries or caches of corn were opened, and they were given liberty to make such use of it as their needs required.”

It is stated 1 that the southern shores of Lake Erie were formerly inhabited “by certain tribes whom we call the Nation of the Cat (or Panther); they have been compelled to retire far inland to escape their enemies, who are farther to the west,” and that this Nation of the Panther has a number of fixed towns, as it cultivates the soil. This shows that the appellation “Nation du Chat” was a generic name for “certain tribes” dwelling south and south east of Lake Erie, whose enemies farther westward had forced at least some of them to migrate eastward. From the list of names of tribes cited by Brebeuf in the Jesuit Relation for 1635 2 the names of four tribes of the Iroquois tongue dwellings of Lake Erie and of the domain of the Five Iroquois tribes occur in the order:

- Andastoerrhonons (Conestoga)

- Scahentoarrhonons (People of Wyoming valley)

- Rhiierrhonons (the Erie)

- Ahouenrochrhonons (Wenrohronon)

But this last name is omitted from the list of tribal names cited from Father Ragueneau’s “Carte Huronne,” recorded by Father LeJeune in his Relation for 1640 3 , because this tribe, in 1639, becoming too weak to resist the Iroquois, having lost the support of an alliance with the Neutral Nation, and being afflicted with an epidemic, probably smallpox, had taken flight, part seeking refuge among the Hurons and part among the Neutral Nation, with which peoples they became incorporated. The Jesuit Relation for 1641 4 says that in the town of Khioetoa, surnamed St Michel, of the Neutral Nation, a certain foreign nation, named A8enrehronon, which formerly dwelt beyond “the Erie or the Nation du Chat (or the Panther Nation),” had for some years past taken refuge.

Father Jean de Brebeuf and Father Joseph Marie Chaumonot started from Ste Marie of the Hurons on Nov. 2, 1640, on a mission to the Neutral Nation; but owing to several causes, chiefly false reports spread among them by Huron spies concerning the nature of this mission, they were coldly received by the Neutrals as a whole, and were subjected to much abuse and contumely. But the Wenrohronon dwelling at Khioetoa lent willing ears to the gospel, and an old woman who had lost her hearing was the first adult person among them to be baptized. Bressani’s Relation for 1653 5 , however, says that among the Hurons the Oenronronnons, whether by true or false report, added weight to the charges against the Jesuits of being the cause of the epidemic and other misfortunes of the people. The foregoing quotation definitely declares that this tribe of the Wenrohronon dwelt before their migration “beyond the Erie” or the Panther Nation. It is therefore probable that this tribe lived on the upper waters of the Allegheny, possibly on the west branch of the Susquehanna, and that it was one of the tribes generically called the Black Minquaas. Writing to his brother on Apr. 27, 1639, Father DuPeron 6 , in reference to the Wenrohronon, says: “We have a foreign nation which has taken refuge here, both on account of the Iroquois, their enemies, and on account of the epidemic, which is still causing them to die here in large numbers; they are nearly all baptized before death.”

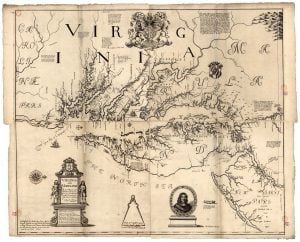

Of the Wenrohronon, Father Bressani, writing in 1653 7 , says that they had then only recently come into the Huron country, and that they “had formerly traded with the English, Dutch, and other heretical Europeans.” Nothing is known of the numbers of the refugee Wenrohronon who fled to the Neutral Nation, but these were in addition to the “more than 600” who arrived in the Huron country in 1639. From Herrmann’s map of Virginia and Maryland in 1670 (published in 1673) much information is derived in regard to the valley of the Juniata River, the west branch of the Susquehanna, and the Wyoming or Scahentowanen Valley. As the Wenrohronon were on hostile terms with the Iroquois tribes, and as they were known to have traded with the English, the Dutch, and other Europeans, it would appear that they must have followed the routes to the trading places on the Delaware and the lower Hudson customarily followed by the Black Minquaas, with whom they seem to have been allied. From Herrman’s map it is learned also that the Black Minquaas lived west of the Alleghany Mountains, on the Ohio or Black Minquaas River, and that these Indians reached Delaware River by means of the Conemaugh, a branch of the Ohio or Black Minquaas river, and the Juniata, a branch of the Susquehanna, and that prior to 1670 the Black Minquaas came over the Alleghany mountains along these branches as far as the Delaware to trade. These Wenrohronon were probably closely allied in interests with the Black Minquaas, and so came along the same route to trade on the Delaware. Diverging eastward from the Wyoming valley were three trails, one through Wind gap to Easton, Pa., the second by way of the Lackawanna at Capouse meadows through Cobb’s gap and the Lackawaxen to the Delaware and Hudson, and the third, sometimes called the “Warrior’s path,” by way of Ft Allen and along the Lehigh to the Delaware Watergap at Easton.

From the journal of Rev. William Rogers with Sullivan’s expedition against the Iroquois in 1779, it is learned that in the Great Swamp is Locust Hill, where evident marks of a destroyed Indian village were discovered; that the Tobyhanna and Middle creeks flow into Tunkhannock, which flows into the head branch of the Lehigh, which in turn joins the Delaware at Easton; that Moosick mountains, through a gap of which Sullivan passed into the Great Swamp, is on the dividing line or ridge between the Delaware and the Susquehanna. This indicates the routes by which the Wenrohronon could readily have reached the Delaware river for trading purposes at a very early date.

LeJeune 8 states that the Wenrohronon, “those strangers who recently arrived in this country,” excel in drawing out an arrow from the body and in curing the wound, but that the efficacy of the prescription avails only in the presence of a pregnant woman. In the same Relation 9 he says that “the number of the faithful who make profession of Christianity in this village amounts to nearly 60, of whom many are Wenrohronons from among those poor strangers taking refuge in this country.” According to the Jesuit Relation for 1672-73 10 there were Wenrohronon captives among the Seneca, along with others from the Neutral Nation, the Onnontioga, and the Hurons; the three nations or tribes last named, according to Father Frémin (1669-70), composed the Seneca town of Kanagaro, the Neutrals and the Onnontioga being described as having seen scarcely any Europeans or having heard of the true God.

The historical references above given indicate that the Wenrohronon, before their wars with the Iroquois and before they were stricken with smallpox, must have been a tribe of considerable importance, numbering at least 1,200 or 1,500, and possibly 2,000 persons.

Citations:

- Jes. Rel. 1647-48, xxxiii, 63, 1898[

]

- Jes. Rel. 1635, 33, 1858[

]

- Jes. Rel. 1640, 35, 1858[

]

- Jes. Rel. 1641, 80, 1858[

]

- Thwaites ed., xxxix, 141, 1899[

]

- Jes. Rel. 1639, xv, 159, 1898[

]

- ibid., xxxix, 141, 1899[

]

- Jes. Rel. 1639, xvii, 213,1898[

]

- Jes. Rel. 1639, xvii, 37,1898[

]

- Jes. Rel. 1672-1673, lvii, 197, 1899[

]