The southern end of Vera Cruz and all of Tabasco in Mexico are not significantly different in appearance than southeastern Georgia. Most of the region is level and humid, with many swamps and natural lakes. The coast of Tabasco is lined with tidal marshes almost identical to those of the coast of Georgia. Although most of the indigenous inhabitants of Tabasco are called Mayas, most are descended from ethnic groups that were not true Mayas, but absorbed varying degrees of Maya culture. One group, the Tamauli were originally refugees from Tamaulipas State in the northeastern corner of Mexico.

This is the land in which the Olmec Civilization rose. After all the major centers of this culture were abandoned around 400 BC, the population density declined and most people lived in relatively small agricultural or fishing villages. In most regions, however, agriculture productivity and diversity continued to increase. These villages would have appeared little different than those “Mississippian” societies in the Southeast that did not build large mounds. The people of Tabasco were apparently illiterate during this era and mainly produced utilitarian items.

Villages were established on islands in the Tabasco tidal marshes. Their occupants both farmed and fished. The Marsh People towns contained no stone structures. Their temples and houses of the elite were placed on earthen mounds, identical in appearance to those of the Muskogeans in the Southeastern United States. The ball courts of the Marsh People were horseshoe shaped earthworks, which were very similar to structures found in Swift Creek Culture towns in the Southeast, an later in Creek towns, up to the late 1700s. Through the centuries the Marsh People became increasingly skilled at the building of large canoes and navigation of coastal waters.

As Teotihuacan grew in power, the coastal people of Tabasco became increasingly involved with coastal trade. Most Mesoamerican societies were terrified of the ocean. However, lacking beasts of burden, shipping bulk goods via water transportation was far more efficient than porters. Apparently, the Marsh People responded by hauling goods up and down the Gulf Coast to the ports nearest major cities and land transportation routes.

Around 300 AD, the Mayas began spreading into Tabasco. They viewed the indigenous peoples of Tabasco as barbarians, but became increasingly dependent on the trade canoes of the Marsh People for transportation of bulk goods. The sudden acceleration of the culture of the Lake Okeechobee Region may reflect the expansion of Tabascan trade networks. (See a later section.) The first evidence of greater sophistication in southern Florida was the construction of canals and roads. Both activities were directly connected with commerce.

Over the centuries the Marsh People (now called Chontal Maya) gradually absorbed more and more cultural influences from neighboring civilizations. Their towns developed on islands. They built mounds and houses that differed little from those built by the Muskogeans in the Southeast. Those Marsh People who traded with areas dominated by the Totonacs developed a trade jargon which mixed Zoque, Totonac and Maya. Those who traded mainly with the Mayas and Arawaks of the Caribbean Basin developed a trade jargon which mixed Zoque, Maya and Arawak.

Chontal is derived from a Nahuatl word, meaning frontier. The Southern American English phrase “edge of towners” best translates the connotation intended by those first called the Marsh People by these names.

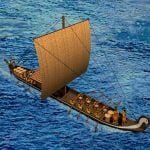

At some time during the Classic Period (200 AD – 900 AD) the Marsh People developed canoes, and then boats, which were constructed out of planks. Plank-built vessels had greater carrying capacity and were faster. The plank built boats eventually evolved into large sea craft propelled by sails and oars, which could traverse ocean waters. They were about the same size and construction as Viking longboats.

The ashes of a supervolcano eruption around 800 AD set the great city of Palenque on fire and caused the general abandonment of the Chiapas Highlands. Palenque was never significantly occupied afterward. The Chiapas and Guatemala Highlands had relatively few inhabitants for the next three centuries. The stone-walled agricultural terraces of the Itza Mayas played a major role in the rise of Classic Maya civilization.

Although (apparently) very few Classic Period Itza Mayas were literate, they were skilled farmers, who shipped their agricultural surpluses to Maya city states that had insufficient agricultural lands to support their high population densities. The sudden loss of these food sources was the first shock wave to stress Mayan society that was soon followed by a series of crop failures in the Maya Lowlands due to droughts.