Inventor of the Cherokee Alphabet

In the year 1768 a German peddler, named George Gist, left the settlement of Ebenezer, on the lower Savannah, and entered the Cherokee Nation by the northern mountains of Georgia. He had two pack-horses laden with the petty merchandise known to the Indian trade. At that time Captain Stewart was the British Superintendent of the Indians in that region. Besides his other duties, he claimed the right to regulate and license such traffic. It was an old bone of contention. A few years before, the Governor and Council of the colony of Georgia claimed the sole power of such privilege and jurisdiction. Still earlier, the colonial authorities of South Carolina assumed it. Traders from Virginia, even, found it necessary to go round by Carolina and Georgia, and to procure licenses. Augusta was the great centre of this commerce, which in those days was more extensive than would be now believed. Flatboats, barges, and pirogues floated the bales of pelts to tide-water. Above Augusta, trains of pack-horses, sometimes numbering one hundred, gathered in the furs, and carried goods to and from remote regions. The trader immediately in connection with the Indian hunter expected to make one thousand per cent. The wholesale dealer made several hundred. The governors, councilors, and superintendents made all they could. It could scarcely be called legitimate commerce. It was a grab game.

Our Dutch friend Gist was, correctly speaking, a contrabandist. He had too little influence or money to procure a license, and too much enterprise to refrain because he lacked it. He belonged to a class more numerous than respectable, although it would be a good deal to say that there was any virtue in yielding to these petty exactions. It was a mere question of confiscation, or robbery, without redress, by the Indians. He risked it. With traders, at that time, it was customary to take an Indian wife. She was expected to furnish the eatables, as well as cook them. By the law of many Indian tribes property and the control of the family go with the mother. The husband never belongs to the same family connection, rarely to the same community or town even, and often not even to the tribe. He is a sort of barnacle, taken in on his wife’s account. To the adventurer, like a trader, this adoption gave a sort of legal status or protection. Gist either understood this before he started on his enterprise, or learned it very speedily after. Of the Cherokee tongue he knew positively nothing. He had a smattering of very broken English. Somehow or other he managed to induce a Cherokee girl to become his wife.

This woman belonged to a family long respectable in the Cherokee Nation. It is customary for those ignorant of the Indian social polity to speak of all prominent Indians as “chiefs.” Her family had no pretension to chieftaincy, but was prominent and influential; some of her brothers were afterward members of the Council. She could not speak English; but, in common with many Cherokees of even that early date, had a small proportion of English blood in her veins. The Cherokee woman, married or single, owns her property, consisting chiefly of cattle, in her own right. A wealthy Cherokee or Creek, when a son or daughter is born to him, marks so many young cattle in a new brand, and these become, with their increase, the child’s property. Whether her cattle constituted any portion of the temptation, I can not say. At any rate, the girl, who had much of the beauty of her race, became the wife of the German peddler.

Of George Gist’s married life we have little recorded. It was of very short duration. He converted his merchandise into furs, and did not make more than one or two trips. With him it had merely been cheap protection and board. We might denounce him as a low adventurer if we did not remember that he was the father of one of the most remarkable men who ever appeared on the continent. Long before that son was born he gathered together his effects, went the way of all peddlers, and never was heard of more.

He left behind him in the Cherokee Nation a woman of no common energy, who through a long life was true to him she still believed to be her husband. The deserted mother called her babe “Se-quo- yah,” in the poetical language of her race. His fellow-clansmen as he grew up gave him, as an English one, the name of his father, or something sounding like it. No truer mother ever lived and cared for her child. She reared him with the most watchful tenderness. With her own hands she cleared a little field and cultivated it, and carried her babe while she drove up her cows and milked them.

His early boyhood was laid in the troublous times of the war of the Revolution, yet its havoc cast no deeper shadows in the widow’s cabin.

As he grew older he showed a different temper from most Indian children. He lived alone with his mother, and had no old man to teach him the use of the bow, or indoctrinate him in the religion and morals of an ancient but perishing people. He would wander alone in the forest, and showed an early mechanical genius in carving with his knife many objects from pieces of wood. He employed his boyish leisure in building houses in the forest. As he grew older these mechanical pursuits took a more useful shape. The average native American is taught as a question of self- respect to despise female pursuits. To be made a “woman” is the greatest degradation of a warrior.

Se-quo-yah first exercised his genius in making an improved kind of wooden milk-pans and skimmers for his mother. Then he built her a milk-house, with all suitable conveniences, on one of those grand springs that gurgle from the mountains of the old Cherokee Nation. As a climax, he even helped her to milk her cows; and he cleared additions to her fields, and worked on them with her. She contrived to get a petty stock of goods, and traded with her countrymen. She taught Se-quo-yah to be a good judge of furs. He would go on expeditions with the hunters, and would select such skins as he wanted for his mother before they returned. In his boyish days the buffalo still lingered in the valleys of the Ohio and Tennessee. On the one side the French sought them. On the other were the English and Spaniards. These he visited with small pack-horse trains for his mother.

For the first hundred years the European colonies were of traders rather than agriculturists. Besides the fur trade, rearing horses and cattle occupied their attention. The Indians east of the Mississippi, and lying between the Appalachian Mountains and the Gulf, had been agriculturists and fishermen. Buccaneers, pirates, and even the regular navies or merchant ships of Europe, drove the natives from the haunted coast. As they fell back, fur traders and merchants followed them with professions of regard and extortionate prices. Articles of European manufacture–knives, hatchets, needles, bright cloths, paints, guns, powder–could only be bought with furs. The Indian mother sighed in her hut for the beautiful things brought by the Europeans. The warrior of the Southwest saw with terror the conquering Iroquois, armed with the dreaded fire-arms of the stranger. When the bow was laid aside, or handed to the boys of the tribe, the warriors became the abject slaves of traders. Guns meant gunpowder and lead. These could only come from the white man. His avarice guarded the steps alike to bear-meat and beaver-skins. Thus the Indian became a wandering hunter, helpless and dependent. These hunters traveled great distances, sometimes with a pack on their backs weighing from thirty to fifty pounds. Until the middle of the eighteenth century horses had not become very common among them, and the old Indian used to laugh at the white man, so lazy that he could not walk. A consuming fire was preying on the vitals of an ancient simple people. Unscrupulous traders, who boasted that they made a thousand per cent, held them in the most abject thrall. It has been carefully computed that these hunters worked, on an average, for ten cents a day. The power of their old village chiefs grow weaker. No longer the old men taught the boys their traditions, morals, or religion. They had ceased to be pagans, without becoming Christians.

The wearied hunter had fire-water given him as an excitement to drown the cares common to white and red. Slowly the polity, customs, industries, morals, religion, and character of the red race were consumed in this terrible furnace of avarice. The foundations of our early aristocracies were laid. Byrd, in his “History of the Dividing Line,” tells us that a school of seventy- seven Indian children existed in 1720, and that they could all read and write English; but adds, that the jealousy of traders and land speculators, who feared it would interfere with their business, caused it to be closed. Alas! this people had encountered the iron nerve of Christianity, without reaping the fruit of its intelligence or mercy.

Silver, although occasionally found among the North American Indians, was very rare previous to the European conquest. Afterward, among the commodities offered, were the broad silver pieces of the Spaniards, and the old French and English silver coins. With the most mobile spirit the Indian at once took them. He used them as he used his shell-beads, for money and ornament. Native artificers were common in all the tribes. The silver was beaten into rings, and broad ornamented silver bands for the head. Handsome breast-plates were made of it; necklaces, bells for the ankles, and rings for the toes.

It is not wonderful that Se-quo-yah’s mechanical genius led him into the highest branch of art known to his people, and that he became their greatest silversmith. His articles of silverware excelled all similar manufactures among his countrymen.

He next conceived the idea of becoming a blacksmith. He visited the shops of white men from time to time. He never asked to be taught the trade. He had eyes in his head, and hands; and when he bought the necessary material and went to work, it is characteristic that his first performance was to make his bellows and his tools; and those who afterward saw them told me they were very well made.

Se-quo-yah was now in comparatively easy circumstances. Besides his cattle, his store, and his farm, he was a blacksmith and a silversmith. In spite of all that has been alleged about Indian stupidity and barbarity, his countrymen were proud of him. He was in danger of shipwrecking on that fatal sunken reef to American character, popularity. Hospitality is the ornament, and has been the ruin, of the aborigine. His home, his store, or his shop, became the resort of his countrymen; there they smoked and talked, and learned to drink together. Among the Cherokees those who have are expected to be liberal to those who have not; and whatever weaknesses he might possess, niggardliness or meanness was not among them.

After he had grown to man’s estate he learned to draw. His sketches, at first rude, at last acquired considerable merit. He had been taught no rules of perspective; but while his perspective differed from that of a European, he did not ignore it, like the Chinese. He had now a very comfortable hewed-log residence, well furnished with such articles as were common with the better class of white settlers at that time, many of them, however, made by himself.

Before he reached his thirty-fifth year he became addicted to convivial habits to an extent that injured his business, and began to cripple his resources. Unlike most of his race, however, he did not become wildly excited when under the influence of liquor.

Se-quo-yah, who never saw his father, and never could utter a word of the German tongue, still carried, deep in his nature, an odd compound of Indian and German transcendentalism; essentially Indian in opinion and prejudice, but German in instinct and thought. A little liquor only mellowed him–it thawed away the last remnant of Indian reticence. He talked with his associates upon all the knotty questions of law, art, and religion. Indian Theism and Pantheism were measured against the Gospel as taught by the land-seeking, fur-buying adventurers. A good class of missionaries had, indeed, entered the Cherokee Nation; but the shrewd Se-quo-yah, and the disciples this stoic taught among his mountains, had just sense enough to weigh the good and the bad together, and strike an impartial balance as the footing up for this new proselyting race.

It has been erroneously alleged that Se-quo-yah was a believer in, or practiced, the old Indian religious rites. Christianity had, indeed, done little more for him than to unsettle the pagan idea, but it had done that.

It was some years after Se-quo-yah had learned to present the bottle to his friends before he degenerated into a toper. His natural industry shielded him, and would have saved him altogether but for the vicious hospitality by which he was surrounded. With the acuteness that came of his foreign stock, he learned to buy his liquor by the keg. This species of economy is as dangerous to the red as to the white race. The auditors who flocked to see and hear him were not likely to diminish while the philosopher furnished both the dogmas and the whisky. Long and deep debauches were often the consequence. Still it was not in the nature of George Gist to be a wild, shouting drunkard. His mild, philosophic face was kindled to deeper thought and warmer enthusiasm as they talked about the problem of their race. All the great social questions were closely analyzed by men who were fast becoming insensible to them. When he was too far gone to play the mild, sedate philosopher, he began that monotonous singing whose music carried him back to the days when the shadow of the white man never darkened the forests, and the Indian canoe alone rippled the tranquil waters.

Should this man be thus lost? He was aroused to his danger by the relative to whom he owed so much. His temper was eminently philosophic. He was, as he proved, capable of great effort and great endurance. By an effort which few red or white men can or do make, he shook off the habit, and his old nerve and old prosperity came back to him. It was during the first few years of this century that he applied to Charles Hicks, a half-breed, afterward principal chief of the nation, to write his English name. Hicks, although educated after a fashion, made a mistake in a very natural way. The real name of Se-quo-yah’s father was George Gist. It is now written by the family as it has long been pronounced in the tribe when his English name is used–“Guest.” Hicks, remembering a word that sounded like it, wrote it–George Guess. It was a “rough guess,” but answered the purpose. The silversmith was as ignorant of English as he was of any written language. Being a fine workman, he made a steel die, a facsimile of the name written by Hicks. With this he put his “trade mark” on his silver-ware, and it is borne to this day on many of these ancient pieces in the Cherokee nation.

Between 1809 and 1821, which latter was his fifty-second year, the great work of his life was accomplished. The die, which was cut before the former date, probably turned his active mind in the proper direction. Schools and missions were being established. The power by which the white man could talk on paper had been carefully noted and wondered at by many savages, and was far too important a matter to have been overlooked by such a man as Se- quo-yah. The rude hieroglyphics or pictoriographs of the Indians were essentially different from all written language. These were rude representations of events, the symbols being chiefly the totemic devices of the tribes. A few general signs for war, death, travel, or other common incidents, and strokes for numerals, represented days or events as they were perpendicular or horizontal. Even the wampum belts were little more than helps to memory, for while they undoubtedly tied up the knots for years, like the ancient inhabitants of China and Japan, still the meager record could only be read by the initiated, for the Indians only intrusted their history and religion to their best and ablest men. The general theory with many Indians was, that the written speech of the white man was one of the mysterious gifts of the Great Spirit. Se-quo-yah boldly avowed it to be a mere ingenious contrivance that the red man could master, if he would try.

Repeated discussion on this point at length fully turned his thoughts in this new channel. He seems to have disdained the acquirement of the English language. Perhaps he suspected first what he was bound to know before he completed his task, that the Cherokee language has certain necessities and peculiarities of its own. It is almost impossible to write Indian words and names correctly in English. The English alphabet has not capacity for its expression. If ten white men sat down to write the word an Indian uttered, the probabilities are that one half of them would write them differently from the other half. It is this which has led to such endless confusion in Indian dictionaries. For instance, we write the word for the tribe Cherokee, and the letter R, or its sound, is scarcely used in their language. Today a Cherokee always pronounces it Chalaque, the pronunciation being between that and Shalakke. On these peculiarities it is not the purpose of this article to enter, but hasten to George Gist, brooding over a written language for his people.

His first essay was natural enough. He tried to invent symbols to represent words. These he sometimes cut out of bark with his knife, but generally wrote, or rather drew. With these symbols he would carry on a conversation with a person in another apartment. As may be supposed, his symbols multiplied fearfully and wonderfully. The Indian languages are rich in their creative power. By using pieces of well-known words that contain the prominent idea, double or compound words are freely made. This has been called by writers treating this subject, the polysynthetic. It is, in fact, a jumbling of sentences into words, by abbreviation, the omitted parts of words being implied or understood. There is one important fact which I will merely note here that is generally overlooked. These compounded words, to a large extent, represent the intrusive or European idea. The names the Indians gave many of the European things were mere DEFINITIONS. Such as “Big Knives,” etc. Occasionally they made a dash at the French or English sounds, as in the word “Yengees” for English, which has finally been corrupted in our language to Yankees.

Of course an attempt at fixed symbols for words was an unhappy experiment in a language one prominent element of which is, the facility of making words out of pieces of words, or compounded words. Besides this difficulty, no language can be taught successfully by means of a dictionary, until the human memory acquires more power. Three years of hopeless struggle with the mighty debris of his symbols left him, although in the main reticent, a mighty man of words. But his labors were not lost. Through that heroic, unaided struggle he gained the first true glimpses into the elements of language. It is a startling fact, that an uneducated man, of a race we are pleased to call barbarians, attained in a few years, without books or tutors, what was developed through several ages of Phoenician, Egyptian, and Greek wisdom.

Se-quo-yah discovered that the language possessed certain musical sounds, such as we call vowels, and dividing sounds, styled by us consonants. In determining his vowels he varied during the progress of his discoveries, but finally settled on the six–A, E, I, O, U, and a guttural vowel sounding like U in UNG.

These had long and short sounds, with the exception of the guttural. He next considered his consonant, or dividing sounds, and estimated the number of combinations of these that would give all the sounds required to make words in their language. He first adopted fifteen for the dividing sounds, but settled on twelve primary, the G and K being one, and sounding more like K than G, and D like T. These may be represented in English as G, H, L, M, N, QU, T, DL or TL, TS, W, Y, Z.

It will be seen that if these twelve be multiplied by the six vowels, the number of possible combinations or syllables would be seventy-two, and by adding the vowel sounds, which maybe syllables, the number would be seventy-eight. However, the guttural V, or sound of U in UNG, does not appear as among the combinations, which make seventy-seven.

Still his work was not complete. The hissing sound of S entered into the ramifications of so many sounds, as in STA, STU, SPA, SPE, that it would have required a large addition to his alphabet to meet this demand. This he simplified by using a distinct character for the S (OO), to be used in such combinations. To provide for the varying sound G, K, he added a symbol which has been written in English KA. As the syllable NA is liable to be aspirated, he added symbols written NAH, and KNA. To have distinct representatives for the combinations rising out of the different sounds of D and T, he added symbols for TA, TE, TI, and another for DLA, thus TLA. These completed the eighty-five characters of his alphabet, which was thus an alphabet of syllables, and not of letters.

It was a subject of astonishment to scientific men that a language so copious only embraced eighty-five syllables. This is chiefly accounted for by the fact that every Cherokee syllable ends in a vocal or nasal sound, and that there are no double consonants but those provided for the TL or DL, and TS, and combinations of the hissing S, with a few consonants.

The fact is, that many of our combinations of consonants in the English written language are artificial, and worse than worthless. To indicate by a familiar illustration the syllabic character of the alphabet of Se-quo-yah, I will take the name of William H. Seward, which was appended to the Emancipation Proclamation of Mr. Lincoln, printed in Cherokee. It was written thus: “O [wi] P[li] 4 [se] G [wa] 6 [te],” and might be anglicized Will Sewate. As has been observed, there is no R in the Cherokee language, written or spoken, and as for the middle initial of Mr. Seward’s name, H., there being, of course, no initial in a syllabic alphabet, the translator, who probably did not know what it stood for, was compelled to omit it. It was in the year 1821 that the American Cadmus completed his alphabet.

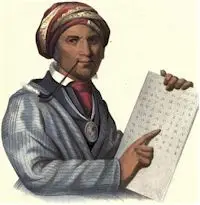

As will be observed by examining the alphabet, which is on the table in the engraving, he used many of the letters of the English alphabet, also numerals. The fact was, that he came across an old English spelling-book during his labors, and borrowed a great many of the symbols. Some he reversed, or placed upside down; others he modified, or added to. He had no idea of either their meaning or sound, in English, which is abundantly evident from the use he made of them. As was eminently fitting, the first scholar taught in the language was the daughter of Se-quo-yah. She, like all the other Cherokees who tried it, learned it immediately. Having completed it without the white man’s hints or aid, he visited the agent, Colonel Lowry, a gentleman of some intelligence, who only lived three miles from him, and informed that gentleman of his invention. It is not wonderful that the agent was skeptical, and suggested that the whole was a mere act of memory, and that the symbols bore no relation to the language, or its necessities. Like all other benefactors of the race, he had to encounter a little of the ridicule of those who, being too ignorant to comprehend, maintain their credit by sneering. The rapid progress of the language among the people settled the matter, however. The astonishing rapidity with which it is acquired has always been a wonder, and was the first thing about it that struck the writer of this article. In my own observation, Indian children will take one or two, at times several, years to master the English printed and written language, but in a few days can read and write in Cherokee. They do the latter, in fact, as soon as they learn to shape letters. As soon as they master the alphabet they have got rid of all the perplexing questions in orthography that puzzle the brains of our children. Is it not too much to say that a child will learn in a month, by the same effort, as thoroughly, in the language of Se-quo-yah, that which in ours consumes the time of our children for at least two years.

There has been a great clamor for a universal language. We once had it, in our learned world, in the Latin, in which books were locked up for the scholars and dead to the world. Language is the handmaiden of thought, and to be useful must be obedient to its changes as well as its elemental characteristics. For the English of three hundred years ago we need a glossary, and to carry down his immortal thoughts in their pristine vigor, must have, every two hundred years, a Johnson to modernize a Shakspeare. To probe the causes of the change of language, to ascertain why even a WRITTEN language is mutable, to pick up this garment of thought and run its threads back through all their vagaries to their origin and points of divergence, is one of the grand tasks for the intellectual historian. He, indeed, must give us the history of ideas, of which all art, including language, is but the fructification. To say, therefore, that the alphabet of Se-quo-yah is better adapted for his language than our alphabet is for the English, would be to pay it a very wretched compliment.

George Gist received all honor from his countrymen. A short time after his invention written communication was opened up by means of it with that portion of the Cherokee Nation then in their new home west of the Arkansas. Zealous in his work, he traveled many hundred miles to teach it to them; and it is no reproach to their intellect to say that they received it readily.

It has been said the Indians are besotted against all improvements. The cordiality with which this was received is worthy of attention.

In 1823 the General Council of the Cherokee Nation voted a large silver medal to George Gist as a mark of distinction for his discovery. On one side were two pipes, the ancient symbol of Indian religion and law; on the other a man’s head. The medal had the following inscription in English, also in, Cherokee in his own

alphabet:

“Presented to George Gist, by the General Council of the Cherokee Nation, for his ingenuity in the invention of the Cherokee alphabet.”

John Ross, acting as principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, sent it West to Se-quo-yah, together with an elaborate address, the latter being at that time in the new nation.

In 1828 Gist went to Washington city as a delegate from the Western Cherokees. He was then in his fifty-ninth year. At that time the portrait was taken, an engraving from which we present to our readers. He is represented with a table containing his alphabet. The missionaries were not slow to employ it. It was arranged with the Cherokee, and English sounds and definitions. Rev. S.A. Worcester endeavored to get the outlines of its grammar, and both he and Mr. Boudinot prepared vocabularies of it, as did many others. In this way, by having more and better observers, we know more of this language than many others, and affinities have been traced between it and some others, supposed to be radically different, which would have appeared in the case of some others, had they been as fully or correctly written.

Besides the Scriptures, a very considerable number of books were printed in it, and parts of several different newspapers existing from time to time; also almanacs, songs, and psalms.

During the closing portion of his life, the home of Se-quo-yah was near Brainerd, a mission station in the new nation. Like his countrymen, he was driven an exile from his old home, from his fields, work-shops, and orchards by the clear streams flowing from the mountains of Georgia. Is it wonderful if such treatment should throw a sadder tinge on a disposition otherwise mild, hopeful, and philosophic?

One of his sons is a very fair artist, using promiscuously pencil, pen, chalk, or charcoal. He served, as a private soldier, in the Union army in the late war, and there, in his quarters, made many sketches. His power of caricaturing was very considerable. If a humorous picture of some officer who had rendered himself obnoxious was found, chalked in unmistakable but grotesque lineaments, on the commissary door, it was said, “It must have been by the son of Se-quo-yah.”

In his mature years, at Brainerd, although approaching seventy, the nerve or fire of the old man was not dead. Some narrow-minded ecclesiastics, because Gist would not go through the routine of a Christian profession after the fashion they prescribed, have not scrupled to intimate that he was a pagan, and grieved that the Bible was printed in the language he gave. This arose simply from not comprehending him. They persisted in considering him an ignorant savage, while he comprehended himself and measured them.

In his old days a new and deeper ambition seized him. He was not in the habit of asking advice or assistance in his projects. In his journey to the West, as well as to Washington, he had an opportunity of examining different languages, of which, as far as lay in his power, he carefully availed himself. His health had been somewhat affected by rheumatism, one of the few inheritances he got from the old fur peddler of Ebenezer; but the strong spirit was slow to break.

He formed a theory of certain relations in the language of the Indian tribes, and conceived the idea of writing a book on the points of similarity and divergence. Books were, to a great extent, closed to him; but as of old, when he began his career as a blacksmith by making his bellows, so he now fell back on his own resources. This brave Indian philosopher of ours was not the man to be stopped by obstacles. He procured some articles for the Indian trade he had learned in his boyhood, and putting these and his provisions and camping equipage in an ox-cart, he took a Cherokee boy with him as driver and companion, and started out among the wild Indians of the plain and mountain, on a philological crusade such as the world never saw.

One of the most remarkable features of his experience was the uniform peace and kindness with which his brethren of the prairie received him. They furnished him means, too, to prosecute his inquiries in each tribe or clan. That they should be more sullen and reticent to white men is not wonderful when we reflect that they have a suspicion that all these pretended inquirers in science or religion have a lurking eye to real estate. Several journeys were made. The task was so vast it might have discouraged him. He started on his longest and his last journey. There was among the Cherokees a tradition that part of their nation was somewhere in New Mexico, separated from them before the advent of the whites. Se-quo-yah knew this, and expected in his rambles to meet them. He had camped on the spurs of the Rocky Mountains; he had threaded the valleys of New Mexico; looked at the adobe villages of the Pueblos, and among the race, neither Indian nor Spaniard, with swarthy face and unkempt hair. He had occasion to moralize over those who had voluntarily become the slaves of others even meaner than themselves, who spoke a jargon neither Indian nor Spanish. Catholics in name, who ate red pepper pies, gambled like the fashionable frequenters of Baden, and swore like troopers.

It was late in the year 1842 that the wanderer, sick of a fever, worn and weary, halted his ox-cart near San Fernandino, in Northern Mexico. Fate had willed that his work should die with him. But little of his labor was saved, and that not enough to aid any one to develop his idea. Bad nursing, exposure, and lack of proper medical attendance finished the work. He sleeps, not far from the Rio Grande, the greatest of his race.

At one time Congress contemplated having his remains removed and a monument erected over them; it was postponed, however.

The Legislature of the Little Cherokee Nation every year includes in its general appropriations a pension of three hundred dollars to his widow–the only literary pension paid in the United States.