On the 30th of June, 1846, the advance of the “Army of the West,” under Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, inarched from Fort Leavenworth for New Mexico. Two troops of dragoons followed in July, and overtook the first division at Bent’s Fort. The remainder of the army, consisting of a regiment of mounted volunteers from Missouri, under Colonel Price, and the Mormon battalion of 500 men, did not march until early autumn. None of the troops followed the regular Santa Fe trail, which led in an almost direct line from Independence to the Mexican settlements, but left it at the Arkansas, and followed up the river to Bent’s Fort. The first division, as it invaded New Mexico, numbered 1658 men, including six companies of dragoons, two batteries of light artillery with sixteen pieces, two companies of infantry, and a regiment of cavalry. The dragoons were regulars and the rest raw recruits. They straggled across the plains very much at will, and took possession of New Mexico without a struggle. The Mexican general, also governor and despot, Armijo, had collected something over 5000 men, and partly completed fortifications at Apache Cañon, the natural approach to Santa Fe. His position there was almost impregnable – a breastwork, thrown across the road where it hangs in midair, with a solid rock wall on one side and a precipice on the other, that could be taken only by a direct assault, under a flanking tire from both sides of the canon – but he and his army retired as the Americans advanced. This has been usually mentioned as an instance of Mexican cowardice, but there is a bit of secret history back of it. There accompanied the expedition a Mr. James Magoffin, an old Santa Fe trader, well acquainted all through the Mexicos, who went, with Lieutenant colonel Cooke, in advance of the army, from Bent’s Fort, on a little mission to Santa Fe. He “operated upon Governor Armijo,” and secured from him a promise to make no stand at the cañon. Armijo’s second in command, Colonel Diego Archuleta, was determined to fight, but Magoffin got rid of him by informing him that Kearny’s mission was only to occupy the country east of the Rio del Norte, and that the country west of the river might easily he seized by him, Archuleta, and held under an independent government. The original intention had been as Magoffin stated, and as he still believed it to be, but Kearny had subsequently received different orders. Kearny was notified that the coast was clear; he made a hurried march, and passed the point of danger in safety. Magoffin, for his services, received $30,000 from the government, which, be said, barely covered his “expenses” in this and a similar move attempted in behalf of Colonel Doniphan, in Chihuahua. The conquest of New Mexico might otherwise have been stopped at Apache Cañon, a place which was destined to be the scene of a decisive battle, but not yet – not until 1862, when the Southern Confederacy was stretching out a brawny arm to seize the mountains.

Armijo’s array was disbanded at Santa Fe, and he fled to the south, leaving the invaders to enter the New Mexican capital, the oldest city in the United States, in peaceful triumph, on August 18. Five weeks later, General Kearny (he had received his commission en route) marched with 300 dragoons to conquer California. On October 12 the Mormon battalion reached Santa Fe. They were undisciplined, poorly equipped, and much worn. They had received permission to bring their families with them, and were badly encumbered with women and children. About one hundred of the more in-efficient men, with all of the women except five of the officers’ wives, were sent to the pueblo on the Arkansas (present Pueblo, Colorado), where they remained all winter. The remainder, under Lieutenant colonel Cooke, marched for California on October 19, taking a route south of the Gila River. Cooke was instructed to report on the practicability of this route for a railroad. His report was favorable, so far as natural obstacles were concerned, and was largely the cause of the Gadsden Purchase. Southern interests prevailed in the administration of 1853, and a Southern Pacific railroad would, of course, have been a desirable institution, when slavery should be carried across the continent under the Southern theory of the Missouri Compromise. On December 14 and 16 Colonel Doniphan’s command, of 856 men, started on the conquest of Chihuahua. The advance, 500 strong, met and routed a force of 1220 Mexicans at Bracito, and this was the only battle fought on New Mexican soil during the conquest. The remainder of the army left in New Mexico, after these detachments had marched, was under command of Colonel Sterling Price, subsequently a noted leader of the Confederacy.

From a military standpoint, the expedition into New Mexico was in many respects remarkable. An “army” of less than 1700 men was sent to reduce, reorganize, and occupy a territory large enough for an empire – a long settled territory, protected by regular troops. It marched across a waste country, peopled only by hostile savages, hundreds of miles beyond its base of supplies, leaving no force to protect its communication. It was so poorly supplied that its rations from Bent’s Fort to Santa Fe were calculated barely to hold out by rapid and uninterrupted marches. Having readied its destination, the entire territory was “annexed,” and its people declared citizens of the conquering nation, thus taking from the invaders the conqueror’s right to levy supplies, although at that time the army was completely destitute of means. Having brushed away these trifling obstacles, the army divides into bands, each of which moves on to conquer equal empires beyond.

Before leaving Sante Fe, General Kearny, under authority of the Secretary of War, organized a provisional government, with Charles Bent as governor. This appointment was probably the best that could have been made. Mr. Bent was one of the pioneers of the Santa Fe trade, and had wide experience all along the frontier. He and his brothers had afforded a hospitable shelter to hundreds of weary wayfarers at their fort on the Arkansas. This structure, built in 1829, was one hundred feet square, with adobe walls thirty feet high. It had bastions at the northeast and southwest corners, armed with cannon. On the inside the apartments were built against the walls, in the Mexican fashion, and in the centre was the robe-press or storehouse for furs. In 1846 it justified Colonel Cooke’s assertion that it was “in reality the only fort at the West.” In 1880 it was “a rude and wild corral, deserted and decaying.” It may also be mentioned, in this connection, that Charles Bent introduced the custom of furnishing the draught oxen of the plains with iron shoes. Besides being a man of practical knowledge, Bent was a man of talent, energy, and patriotism. He had married a Spanish lady, and established his residence at Don Fernandez de Taos, where Kit Carson, Judge Beaubien, the St. Vrains, and other pioneers had also settled.1 The community over which Bent was called to rule was complex. The Americans were trifling in number, outside the military. The people generally may be classed as Mexicans, pueblos, and wild Indians, though there existed in abundance every imaginable gradation in blood and habits between these classes. The wild Indiana were treated with, to some extent, but were not under control. They were at first very friendly to the Americans because of their enmity to the Mexicans; but when the country passed under American rule, and the government was put under obligations to protect its Mexican citizens, their friendship went with the cause of it. The large majority of the Mexicans were then, as now, in the state of peonage, a sort of cross between slavery and service, owned and controlled by a few grandees, or ricos, as they are called. They were avaricious, revengeful, fickle, and treacherous. The Pueblos were the most interesting and, indeed, the most reliable class of the three.

They are not a nation or tribe, as is the too common impression, but include a number of tribes, speaking six distinct languages. They are, as the name signifies, Indians who live in permanent towns. Most of them were Christianized, after a fashion, at an early date, and they are sometimes, accordingly, spoken of as the Christian or Catholic Indians, Thc term is misleading, for a Catholic New Mexican Indian is not necessarily a Pueblo, nor is a Pueblo necessarily a convert. At the time of our conquest they inhabited the twenty-six villages which they still occupy. Of these the seven villages of the Moquis are separated from the rest, being situated in that northeastern portion of Arizona which is cut off by the Little Colorado River. The original name of the Moquis was Hapeka. They received the name Moqui, which means “death,” many years ago, at a time when smallpox was ravaging their villages. Zuñi is also within the bounds of Arizona, just on the edge of the Pacific slope. It is a well built town, covering some ten acres of land, and having a population of about 3000. The other villages are situated in the valley of the Rio Grande, extending over two hundred miles, interspersed with Mexican towns, from Taos, on the north, to Ysleta, on the south. Of the origin of these Indians nothing certain is known. They were there, and living in their pueblos, when Alvar Nuñez and his three companions, the sorry remnant of the Floridan expedition of Pamfilio Narvaez, passed through the land, from the Gulf of Mexico, seeking their way to the Spanish settlements. This was prior to 1538, and was the first time that white men had reached their country. They were then, as now, an agricultural people, raising grain and vegetables. They also manufactured pottery and cotton fabrics, but this latter art they now appear to have lost. There is no trace of even the rudest forms of poetry or music among them. Some have thought the Pueblos to be of the same stock as the Incas of Peru, a theory whose only support is that they are sun worshippers, and communicate to some extent by knotted cords. The opinion that they are the remains of a former Aztec settlement of the country has received much support. They have traditions of an early government by the Montezumas, and are said still to preserve the sacred fires instituted by them. On the other hand, these people were utterly unknown in Mexico at the time of the Spanish conquest, and many of the best authorities doubt that the Aztecs came from the North at all.

There is a general tendency to believe that they are a distinct people, having no connection with any of the other civilized aborigines of America. The best evidence of this is found in the hundreds of ruins, lying principally to the southwest of the present villages, similar to them in structure, and which cannot be identified with any other architecture. These ruins extend over a territory more than four hundred miles in length, from northeast to southwest, and varying in width from fifty to one hundred miles, besides some scattered once outside these limits. They are usually collected in groups, some of the cities having evidently contained thousands of inhabitants. The largest building yet discovered is three hundred and fifty feet by one hundred and fifty, surrounded with embankments, Monts, outer walls, and reservoirs. It stands in the centre of a city near Salt River, some twenty miles above the town of Phoenix, Arizona. There are also buildings which appear to have been joined, surrounding courts of such magnitude that no roof could have covered them. All through this country are the ruins of immense acequias (irrigating canals) – sometimes written zequia), some of which can yet be traced through lengths of fifty miles or more. Their grade is so perfect that modern engineers have been able to gain an inch of fall to the mile over theirs. Another fact showing a knowledge of engineering is that many of their towns and works are laid out with regard to the points of the compass. The ledges of rock in this country abound in hieroglyphs. Pottery and stone implements are found in quantities, but no implements of iron and no bones of large domestic animals have been discovered in these ruins. The people who built these towns must have had all this land under cultivation, and must have been more advanced in the arts and sciences than the Pueblos. This, however, does not show that the Pueblos are not their descendants, for they may have retrograded. As I have already mentioned, they have lost the art of manufacturing cotton fabrics since the whites knew them, and this is an art which the prehistoric race had, for cotton cloth has been found in the cliff dwellings, six feet below the present surface of the floors. It is also quite probable that they have had and lost the art of writing. In the Pueblo of Zuñi is said to be preserved a book of dressed skins, the pages of which are covered with figures and characters of all shapes, in red, blue, and green. They say it is a history of their tribe, which has moved fourteen times, this being their fifteenth settlement. The last man who could read it died many years ago, and it is now kept as a sacred relic. A more enticing field for some American Champollion could hardly be imagined.

The common characteristic of the ancient and modern races is the pueblo itself, which is a large building, of many rooms, capable of accommodating numerous families. Some of them are built of stone, some of adobes, and some are caves cut in the cliffs, with artificial structure added where necessary. They range from two to eight stories in height; the walls of each succeeding story set back from those of the one below, making a succession of terraces to the top of the building. There are no entrances through the lower walls. The interior is reached by mounting from terrace to terrace on ladders, and then descending through trapdoors. At night the ladders are pulled up, and the inmates rest out of reach of their enemies. Each story is divided into tiers of rooms, the outer ones lighted by narrow windows; the inner ones, which are used chiefly as storerooms, being dark. In each pueblo is a large room called the estufa, which serves as a council chamber, a place of worship, and a public hall. Some of these pueblos have furnished a habitation for hundreds of people for centuries. In general, the religion of this people is an odd mixture of Catholicism and paganism, but the different villages vary widely in their tenets. In government and laws the villages are entirely independent. They hold yearly elections of their officers, who are a governor or cacique, a judge or alcalde, a constable, and a war captain, the last having no authority in time of peace. They have also a council of wise men in each village who act as advisors to the governor.

The Pueblos are ignorant and superstitious, as compared with modern civilized peoples, but they are industrious, honest, sober, frugal, brave, and peaceable. When first conquered by the Spanish they were reduced to a grievous state of slavery, which they endured restlessly till 1680. In that year, roused by persistent attempts to force Catholicism on them, they rebelled and drove the Spanish out. They held their country for thirteen years before they could be re-conquered. Though then forced to accept the Spanish faith, they were treated more liberally, but several revolts occurred afterwards. At the time of the American conquest they were practically in harmony with the Mexican population, and accepted the new government with equal resignation.

Notwithstanding the good grace with which the people had submitted, many of them were sore over the cowardly manner in which the country had been surrendered, and were ready for the machinations of designing men. Such men were there, and, as the various bodies of troops left for other points, they began to plot. This was only natural. When a Mexican has nothing else to busy him he gets up an insurrection. Indeed, some of them would neglect a profitable business for this purpose. The leaders in this project were the disappointed Colonel Diego Archuleta and his friend Tomas Ortiz, men of talent and enterprise, made doubly desperate by intemperance and unlucky gambling. They were supported by a number of prominent ricos and priests, and had enlisted the aid of the Taosan Indians, as well as the Mexicans. The rising was to have been on the 19th of December, but, owing to defective organization, it was postponed to Christmas Eve. At dead of night the church bells were to be rung, and, at that signal, the conspirators were to sally forth, seize the artillery, and murder every American and friendly native in the province. Three days before the time of attack the plot was revealed to the Americans. An ex-officer of the Mexican army was arrested, and a list of the disbanded soldiers of Armijo was found on him. Several others supposed to be implicated were arrested, but Ortiz and Archuleta escaped to the south and reached Mexico. Early in January Governor Bent issued a proclamation calculated to quiet the people. The insurrection was believed to have been suppressed by these measures, but the leaderless organization remained like a giant blast in the midst of the social fabric, ready to explode at the touch of any spark. The explosion came on January 19, 1847.

Early in the morning of that day a large number of Pueblos assembled at Don Fernandez and insisted on the release of three of their tribe, notorious thieves, who were confined in the calaboose. The sheriff, Stephen Lee, seeing no means of resistance at hand, was about to comply with their demand, when the Mexican prefect, Cornelio Vigil, appeared and forbade him, at the same time denouncing all the Indians as thieves and scoundrels. This was the needed spark. The Indians sprang on him with the fury of devils, killed him, cut off his limbs, cut him to pieces, and then released the prisoners. Lee escaped in the confusion, but was followed and killed. The blood of the Indians was now at fever heat, and the slumbering impulses of savagery came into control again, as they were incited to further action by the Padre Martinez and others of the original conspirators. They hastened to the house of Governor Bent, who had been in Fernandez for several days. He was yet in bed, but was aroused by his wife and warned of the imminent peril. He quickly realized the situation. Telling his wife it was useless to attempt fighting such a mob singlehanded, he sprang to a window which opened into an adjoining house and asked for assistance. The Mexicans there told him it was useless to hope for aid – that he must die. At the same time he was wounded by two arrows from Indians who had mounted the housetops. He withdrew into his room and the Indians began tearing up the roof. With all the calmness of a noble soul he stood awaiting his doom. His wife brought him his pistols and told him to fight, to avenge himself, even if he must die. The Indians were exposed to his aim, but he replied: ‘” No; I will not kill any one of them; for the sake of you, my wife, and you, my children. At present, my death is all these people wish.” As the savages poured into the room he appealed to their manhood and honor, but in vain. They laughed at his plea. They told him they were about to kill every American in New Mexico and would begin with him. An arrow followed the word – another, and another – but the mode was not swift enough. One, more impatient, sent a bullet through his heart. As he fell, Tomas, a chief, stepped forward, snatched one of his pistol, and shot him in the face. They took his scalp, stretched it on a board with brass nails, and carried it through the streets in triumph.

James W. Leal, a private in the La Clede Rangers, fared even worse. He was on furlough, and had been appointed prosecuting attorney for the northern district. They seized him at his house, stripped him naked, and marched him about the streets, pushing arrows into his flesh, inch by inch, as they dragged him along. They conducted him again to his house, where they made a target of him, and amused themselves by shooting at his eyes, his nose, and his mouth. They tore away his bleeding scalp, and left him writhing in agony while they went in search of other victims. Several hours after they began their fiendish work they returned and finished it by shooting him to death with arrows. His body was thrown out, and the hogs had eaten part of it, when Mrs. Beaubien, the Spanish wife of Judge Beaubien, learned of it, and had some men bury the remains. Meanwhile the Beaubiens were in deep affliction. There had been at their house another member of the La Clede Rangers, Robert Gary by name, but he had gone to Santa Fe on the day previous with Judge Beaubien. The Indians, supposing him to be there still, went to the house, where they were met by Narcissus Beaubien, the judge’s son, a promising youth of twenty, who had just finished his education in the States. They murdered him, probably mistaking him for Gary. They also murdered Pablo Harvimeah, a friendly Mexican. General Elliott Lee, of St. Louis, was in Fernandez at the time. He fled to the house of a friendly priest, who concealed him under some sacks of wheat. The Indians searched for him some time before they discovered his hiding place. They were then about to drag him forth and kill him, but the priest interceded and persuaded them to go away. They returned several times, with renewed determination to have his life, but the padre succeeded in saving him. The only other American who escaped from the place was Charles Towne. His father-in-law, a Mexican, mounted him on a swift mule, and he brought the news of the massacre to Santa Fe.

The insurrection was now under full headway. Messengers were sent in every direction to urge the people to rise against the Americans. The Rio Abajo (the lower river country, as distinguished from the Rio Arriba, or upper river country) was especially called on for aid. On the evening of the same day eight Americans were captured, robbed, and shot, by the insurgents, on the road near Mora, a town of some 2000 inhabitants situated about seventy five miles east of Santa Fe, near the road to the States. They were Romulus Culver, L. L. Waldo, Benjamin Praett, Louis Cabano, Mr. Noyes, and three others in company. On the same day also two Americans were killed on the Colorado, and shortly afterwards several grazing camps were attacked, the guards killed, and the cattle run off. These outrages were by Mexicans, and are not properly within our province. I will mention, however, that Captain Hendley, who was stationed near Mora, attacked the Mexicans there on January 24. He was killed and his force repulsed. On February 1, Captain Morin, with 200 men, attacked and destroyed the town, with everything in it; but Cortez, the Mexican leader there, escaped. Let us now return to our Indians.

Twelve miles above Don Fernandez the road through the Valle de Taos crosses the Arroyo Hondo (Deep Creek. Arroyo means a small river, but is commonly used in the West to indicate any land subject to overflow, from a dry gulch to a river bottom). At this place Simeon Turley, an American, had established a mill and a distillery. These buildings, with the stables and outhouses, were enclosed in a square corral. On one side, at a distance of about twenty yards, ran the stream; on the other the ground was broken, and rose abruptly, at a short distance, forming the bank of the ravine. At the rear was a little garden, to which a small gate opened from the corral. Turley was not apprehensive of danger, and, indeed, had personally little cause to be. He had married a Mexican woman. He was well known and generally liked. He was celebrated for his generosity and humanity; no needy man was turned unaided from his door. He had even been warned of the intended revolt, but had paid no attention to the warning. On the morning of the 19th one of his employees, named Otterbees, who had been to Santa Fe on an errand, rode up to the mill at full speed. He reined his panting horse only long enough to tell them that the Indians had risen and massacred Governor Bent and others, and then galloped on. Even then Turley did not anticipate any molestation, but there were eight white men, mostly American trappers, at the mill, and on their solicitation the gates of the corral were closed and preparations made for defense. In a few hours a large crowd of Pueblos and Mexicans, armed with guns, bows, and lances, made their appearance, and, advancing under a white flag, demanded the surrender of the place and the men. They told Turley that they would spare his life, but that the other Americans must die; that they had killed the governor and all the Americans at Fernandez, and not one was to be left alive in New Mexico. It was a hard choice for Turley. On one side was his life, his family, and his property. On the other were the lives of eight of his countrymen. He did not hesitate for an instant. His answer was: I will never surrender my house or my men. If you want them you must take them.” The enemy drew off, consulted for a few minutes, scattered, and began their attack. Under cover of the rocks and cedar bushes, which were abundant on all sides, they surrounded the corral and kept up an incessant but ineffectual fire on the mill. The defenders did better. They had blocked the windows, leaving only loopholes, and from one of these there sped a ball with unerring aim at every assailant who showed himself. During the day several were killed, and parties were kept busy bearing the wounded out of the cañon. Nightfall brought no material change in the condition of the besieged. They wasted no ammunition in the dark, but passed the night in running bullets, cutting patches, and completing the defenses of the place. It was the last night on earth for all but two of them.

The attacking party originally numbered about five hundred, and was constantly growing. They kept up a continual fire during the night at the upper part of the buildings, while a part of them affected a lodgment in the stables and outbuildings. One squad reached a shed which joined the main building and attempted to secure an entrance by breaking through the wall, but its combined strength of logs and adobes resisted all their efforts. When morning broke, this party still remained in the shed, which proved unavailable, however, as a point of attack. Finding that they could not injure the besieged from that position, they began running across the open space to the stables beyond, and several had done so in safety before the men in the mill noticed them. The next who attempted to cross was a Pueblo chief. He dropped dead in his tracks near the centre of the open space. An Indian at once dashed out and attempted to drag his body in. A rifle cracked, the Indian leaped into the air, and fell across the body of his chief, shot through the heart. A second followed, and a third, only to meet the same fate. Then three Indians rushed to the place together. They had laid hold of the chief’s corpse by the head and legs and lifted it up, when three puffs of blue smoke came from the loopholes, three rifles rang out, and three more bodies were added to the ghastly pile. Then a great shout of rage went up from the besiegers, and a rattling volley was poured into the mill. Until then no one in the mill had been injured, but from this volley two men fell mortally wounded. One was shot through the loins and suffered great agony. He was removed to the still house and placed on a pile of grain, which was the softest bed at hand. The conflict then lulled a little.

In the middle of the day the assailants, growing more furious at their baffled attempts, renewed the attack more fiercely than ever. The little garrison stood to their defense as coolly and bravely as before, and their rifles spoke death to every Indian or Mexican who exposed himself. But their ammunition was failing, and, what was worse, the enemy had succeeded in firing the mill. It blazed up fiercely and threatened destruction, but the inmates succeeded in quenching the flames. While they were thus occupied the assailants entered the corral and vented their rage by spearing the hogs and sheep, which had been gathered there for protection. As fast as the flames were extinguished in one place they broke out in another. The assailants were constantly increasing in numbers. It was evident that a successful defense was hopeless. The besieged therefore determined to fight until night, and then each one make his escape as best he could. Just at dusk two of the men ran to the wicket gate that opened into the garden, in which were a number of armed Mexicans. They rushed out at the same time and discharged their rifles full in the faces of the crowd. In the confusion that ensued one of them threw himself under the fence, and from there he saw his companion shot down and heard his cries for mercy, mingled with shrieks of pain, as the assassins pierced him with their knives and lances. He lay motionless under the fence until it was quite dark, and then escaped to the mountains. After travelling day and night, with scarcely an hour’s rest, he finally succeeded in reaching a trader’s fort, half dead with hunger and fatigue. Turley also succeeded in reaching the mountains unseen. There he met a Mexican with whom he had been on intimate terms for years. He was mounted. Turley offered him his watch for the use of the horse, the animal itself not being worth one third as much, but was refused. Still the inhuman hypocrite affected compassion for him and promised to bring him assistance if he would remain at a certain rendezvous. He then proceeded to the mill and informed the Indians of Turley’s whereabouts. A large party of them hurried to the place and shot him to death. One other man made his escape and reached Santa Fe in safety. The others, Albert Turbush, William Hatfield, Louis Tolque, Peter Roberts, Joseph Marshall, and William Austin, perished at the mill. Everything about the place that the victorious party desired they carried off, and the rest was burned. On the morning of the 21st all that remained of Turley’s mill was a smoldering ruin – the smoking ashes of a bloody funeral pyre.

The news of the murders at Don Fernandez was brought to Colonel Price on the 20th, and on the same day he intercepted some of the messengers sent by the insurgents to the Kio Abajo, on whom were found letters which showed their plans in full. All the Americans in Santa Fe were thrown into a fury of excitement and indignation when they heard of the horrible treatment of their universally beloved governor, Colonel Price reviewed the troops, and announced to them that he would inflict summary punishment on the guilty He at once sent orders to Major Edmonson to come up from Albuquerque with hie regiment of mounted Missouri volunteers and garrison Santa Fe. Captain Burgwin, who was at the same place with two companies of dragoons, was instructed to leave one company at Santa Fe and join Price in the field with the other. Felix St. Vrain, Bent’s partner, organized a company of mounted volunteer “avengere,” which was joined by merchants, clerks, teamsters, and mountaineers, to the number of fifty. Without waiting for the troops from Albuquerque, Price marched for Taos on the 23d, with 353 infantry, four 12-pound howitzers, and St, Vrain’s company. On the next day they met the insurgents near La Cañada, about l,500 strong, seemingly anxious for a fight, but a brief cannonade and a gallant charge put them to flight. A detachment of them undertook to destroy the wagon train, but Captain St, Vrain’s force beat them off. Our loss was two killed and seven wounded; the insurgents left thirty-six dead on the field. On the 28th the command reached Luceros, and was there joined by Captain Burgwin with two companies, one mounted, and Lieutenant Wilson of the 1st dragoons, with a 6pounder, increasing the command, rank and file, to 479 men.

The succeeding day it was learned that the enemy, 650 strong, were posted in the cañon leading to the town of Embudo. As the road through the cañon was impassable for artillery and wagons, a detachment of 180 men, under Captain Burgwin, including St. Train’s volunteers, was sent to dislodge them. This detachment reached the enemy’s position and found them posted on both sides of the narrow gorge, screened by forests and masses of rock. The Americans dismounted and charged up both sides of the cañon, in open order, firing rapidly. The enemy broke at once and fled towards Embudo, with a speed which made pursuit vain. The detachment occupied Embudo that night, and rejoined the main body at Trampas on the 31st. Their loss at Embudo was one killed and one – Dick, the colored servant of the late governor – severely wounded; the insurgents lost twenty killed and sixty wounded. The march from Trampas was one of great hardship, the road being up Taos mountain and down into the valley beyond. The troops had to wade through deep snow, two and three feet of it at the summit, and break a road for the wagons. They had no tents, and their blankets were carried on their backs. They bore their trials with the uncomplaining patience of veterans, although many were frostbitten, and all were jaded. The exposure of this march proved to be as fatal as the arms of the enemy, for numbers contracted fevers which resulted in death; among these were Lieutenants Lackland and Mansfield.

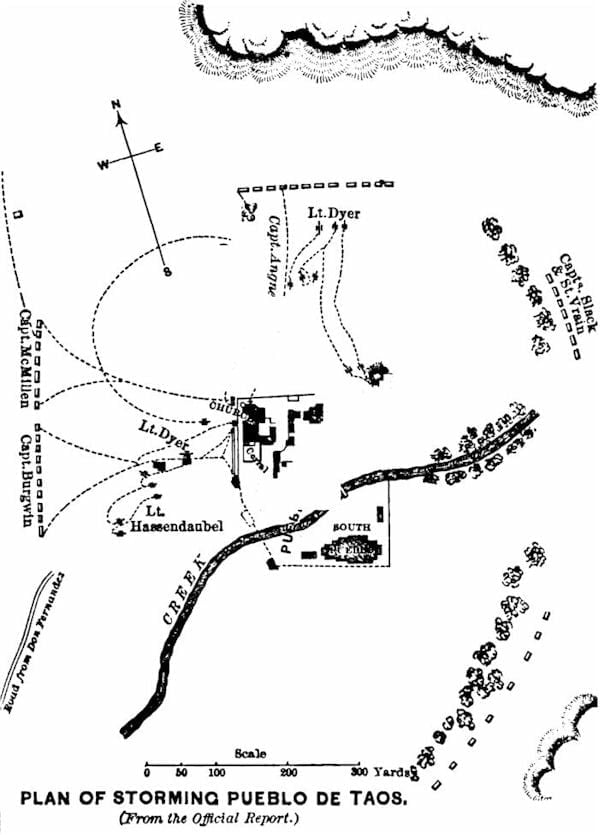

The command marched up the valley, passing through Don Fernandez de Taos without any opposition, until, on the afternoon of February 3, they reached the pueblo where the enemy were strongly fortified. The village was entirely surrounded by adobe walls and strong pickets, the enclosure being almost a rectangle in shape, about 250 yards long and 200 yards wide. In the northeast and southeast corners were the two large houses, or pueblos proper, rising like pyramids to heights of seven and eight stories, and capable of sheltering 800 men each. In the northwestern corner was the large adobe church, opening to the south in a corral. Between each of these buildings and the walls was an open passageway. There were also a number of small buildings within the enclosure, mostly to the north of the small stream which enters near the southwest corner and passes out on the east side. The exterior wall and those of the buildings were pierced for rifles, and every point of the exterior wall was flanked by projecting buildings at the angles.

The little army halted before this stronghold of the ancient time. Its inhabitants hurled their jeering defiance from their housetops, or peered with curious eyes through their narrow windows at the deluded foe who had expected to injure them. They were face to face; the oldest civilization of the United States and its newest; the one confident in its numbers and its massy walls, the other in its engines of war, its discipline, and its valor. There they fought their battle out, and settled their differences forever. The artillery was unlimbered, and played on the west side of the church for two hours and a half, but with no perceptible effect. At the end of that time, as the men were suffering from the cold, and the ammunition wagon had not come up, the Americans retired to Fernandez for the night. Colonel Price, in the meantime, had thoroughly reconnoitered the village, and decided on his plan of attack. The Indians on the housetops mistook the withdrawal for a retreat, and, with insulting gestures and epithets, told the Americans to come on if they wanted to be killed. The invitation was accepted early on the following morning, the village being surrounded and work begun in earnest. Captain Burgwin, with the dragoons and two howitzers, was stationed on the west side, opposite the church. Captains Slack and St. Vrain, with the mounted men, were placed on the east side, to prevent the escape of fugitives to the mountains. The balance of the command was on the north side, with the remaining two howitzers and the 6poundcr. The batteries opened upon the village at nine o’clock, and continued firing till eleven. Finding it impossible to breach the walls with the cannon, the troops charged on the north and west sides. They gained the shelter of the church walls, and some began their attack on the thick clay barrier, while others mounted a rude ladder and fired the roof. The artillery meanwhile plied the village with grape and shell. The battle was becoming more exciting. The soldiers cut holes through the church walls and threw in lighted shells with their hands. The Indians and their allies maintained a rambling fire on them from the church and the bastions. Captain Burgwin, with Lieutenants McIlvaine, Royall, and Lackland, climbed over into the corral at the front of the church, and tried to force the door.

In this exposed position the gallant captain received a bullet wound which disabled him, and from which he died on the 9th. The fatal shot is supposed to have been fired by a Delaware Indian desperado, well known on the frontier as “Big Negro,” who had joined the insurgents, and afterwards made his escape to the Cheyennes and Comanches. He claimed to have killed five Americans at the pueblo. The officers who followed Burgwin found their efforts fruitless, and retired behind the wall. At half past three in the afternoon the 6pounder was run up within sixty yards of the church, and in ten rounds made a practicable breach of one of the holes cut by the axe men. The gun was brought within ten yards, and three charges of grape and a shell were thrown in. Then the storming party poured in, under cover of the dense smoke which tilled the church. They occupied it without opposition, no Indians being seen except a few who were hurrying out of the gallery, where an open door admitted the air. Another charge was made at once on the north side, and the enemy then abandoned the western part of the town altogether. Some took refuge in the two large houses, while others tried to escape to the mountains on the cast. They might better have tried any other place, for here were the “avengers,” who were only desirous of an opportunity to earn their title. Fifty-one of the fugitives fell by their hands, and only two or three escaped. Among those killed was Jesus de Tafoya, one of the leaders, who was wearing Governor Bent’s coat and shirt. He was shot by Captain St.Vrain. When night fell, the troops moved quietly forward and occupied the deserted buildings of the Indians. In the morning the Indians, men and women, bearing white flags, crucifixes, and images, came to Colonel Price, and on their knees begged for mercy. They had lost about 150 killed, besides the wounded, out of a force of some 650, and the colonel thought that their punishment was almost enough. He granted their prayer, on condition that they surrendered a number of the leading offenders, especially their chief Tomas, who has been mentioned in connection with Governor Bent’s murder, and who had taken an active part throughout.

The principal Mexican leaders of the insurrection were Tafpoa, Pablo Chaves, Pablo Montoya, and Cortez, the leader at Mora. Chaves was killed at Embudo, and Tafoya at the pueblo. Montoya, a man of considerable influence, who styled himself the Santa Anna of the North, was tried by court-martial and hanged in the presence of the army, at Fernandez, on February 7. Tomas was shot by a sentinel while trying to escape from the guardhouse at the same place. Fourteen of the insurrectionists were indicted for the murder of Governor Bent, and tried at Taos. They were all convicted and executed. Antonio Trujillo and several others were sentenced to be hanged on convictions of treason, but were pardoned by the President on the ground that Mexican citizens could not commit treason against the United States while actual war existed between the two countries. The army returned to Santa Fe, and there, on the 13th, the bodies of Governor Bent and Prosecuting attorney Leal were buried with civic, masonic, and military honors. After a third interment, the remains of Governor Bent now lie in the Masonic Cemetery at the New Mexican capital, beneath a handsome monument and honorable epitaph.

On no other occasion have the Pueblos proven hostile to the Americans, and in this instance the Taosans only were guilty. Even in the insurrectionary troubles of the succeeding summer the Pueblos took no part. For what they did they were not really very blameworthy, except for their savage cruelty. What feelings of patriotism they had attached them to the Mexicans, and their M(3xican leaders had persuaded them that they could easily drive out the Americans, capture Santa Fe, and repossess the country. Insurrection was an everyday affair with the entire community, and assassination was the popular method of warfare. Fiendish as their crime was, it was little worse than was perpetrated on soldiers of our army by Mexicans in the course of the war; and the recollection of it, even as an historical fact, has been almost blotted out by their faithful and trustworthy conduct in the years that followed. At the time of our conquest the number of the Pueblos was between ten and eleven thousand, but they have now declined to about nine thousand, besides having degenerated somewhat physically. The cause of their decadence is probably their continuous intermarriage in the same pueblo, the young men very rarely seeking wives from other villages. They have been judicially recognized as citizens of the United States, but they have not exercised the right of suffrage, under the laws of New Mexico.2 The old Spanish grants were confirmed to them in 1858 by Congress, and on these they pursue in peace their quiet agricultural life. The only troubles that have ruffled their quietude in late years were some slight religious dissensions, for which they were not much to be blamed. In 1868 a new policy was inaugurated for the control of the Indians, and under it the various tribes were assigned to the different churches for missionary work. This was done with the best of intentions, but the military impartiality with which the allotment was made seemed to indicate a desire to give each denomination a fair show at the heathen, rather than to gratify any sectarian preferences of the Indians themselves. In the distribution the Pueblos fell to the Campbellites, and afterwards, on their failure to act, to the Presbyterians. Calvinism would not hinge with even the crude Catholicism of the Pueblos, and a period of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion” ensued. In 1872 the caciques of fifteen pueblos protested against their established church, and in 1874 appealed to the government. The matter was satisfactorily adjusted and peace has since reigned supreme.