In 2007, Architect Richard L. Thornton, a Creek scholar and member of the People of One Fire research alliance began sporadically looking online for the Migration Legend. 1 He had no success for the next seven years.

On December 21, 2012, Thornton was a key cast member on the premier of the hit History Channel Series, “America Unearthed.” 2 The program was about the evidence of Maya refugees settling in Georgia and becoming some of the ancestors of the Creek Indians. After the program was broadcast in the United Kingdom in early 2013, Thornton received a brief, congratulatory email from Clarence House, the official residence of HRH Prince Charles that wished him the best of success in future research.

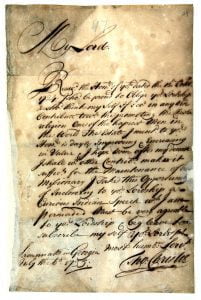

A few days later, Thornton mailed a formal letter directly to Prince Charles and the Clarence House Staff asking for their assistance in finding the lost Migration Legend of the Creek People. About a month later, he received an email from Dr. Grahame Davies, the famous Welsh poet, who had recently been hired as Assistant Private Secretary for Public Relations at Clarence House. Davies offered his assistance and asked for more details about the disappearance of the documents. Those were provided by Thornton.

About six months later, Thornton received an email from Davies stating that the Migration Legend documents had been forwarded by King George II to the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Wake. Their last known whereabouts were somewhere in the archives or warehouses of the Church of England.

At that time, there was no online record of the Church of England’s archives. Thornton sent a letter by conventional mail to the Church of England concerning the missing documents, but received no response. An email to the Church of England’s Archivist eventually got a response that he would have to come in person to the UK to look for the documents himself. Nothing further was done on the search.

In late January of 2015, Thornton was looking for copies of a treaty between Great Britain and the Creek Confederacy in the online web pages of the UK National Archives, when he spotted a notice that the UK National Archives had recently catalogued the archives of Lambeth Palace, the official residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. For the next week, he used various key words in the search tab in hope of finding the Migration Legend. Then on February 4, 2015, he tried the simple combination of Colony of Georgia – Creek Indians. There popped up a package of documents dated June 7, 1735 through July 6, 1735, which the citation said was a description of the political structure and history of the Creek Indians.

An email was immediately sent to the Lambeth Palace asking for digital copies of the documents. There was an automated response that the Lambeth Palace Library would be closed for renovations until August 2015. It could take up to two weeks for a response from staff.

Thornton waited for six weeks and there was still no response from Lambeth Palace. He contacted the British Consul in Atlanta and asked for assistance. There was no response. He contacted the UK Cultural Attaché’ in Washington, DC. There was no response. He called up the National Offices of the Anglican Church in the United States, located in Conyers, GA. Their staff was sympathetic, but explained that they were not on good terms with the Church of England, because of a difference of opinion concerning ordination of women. Their staff recommended that he contact the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta for help. Bingo . . . the Public Relations Director of the Diocese, Nancy Ross, knew two people at Lambeth Palace, who could walk down the hall and ask the library staff to answer their email.

T. F. Lotter, “A Map of the County of Savannah,” 1735

On April 29, 2015, Thornton received an email from the Church of England Archives. On the previous day, the box containing the English translation of the Migration Legend of the Creek People had been opened. The documents were in fairly good condition after 280 years, although unfortunately, Thomas Christie had written on both sides of the paper and the ink has saturated through. Because they had been so tardy in responding, the library would pay for high resolution photography of the original documents and would be sending digital copies within a month. The box containing the Migration Legend also contained several other documents about the Creeks Indians that were apparently written by Thomas Christie. They included an eyewitness account of a Creek Green Corn Festival. 3

The biggest surprise is that two previously lost colonial documents stated that the original People of One Fire or Creek Confederacy was composed of four tribes, the Alabamu, the Kaushete, the Apike and the Chickasaw. 4 No one had ever considered the Chickasaw to be part of the Creek Confederacy. No one had ever considered the possibility that the Koweta were once enemies of the original Creek confederacy. These documents made it clear that the Kausheta and Chickasaw had maintained a close relationship up to the present. However, the Chickasaw and Alabamu were not part of the confederacy formed by the town of Koweta in 1717.

Perhaps the next most remarkable aspect of the colonial documents, discovered in 2015, is that both Chikili and Tamachichi considered Yamacraw Bluff as being the original Creek town and stated that the Creek’s first emperor was buried there. 5 While chatting with James Oglethorpe, Tamachichi pointed to a conical burial mound near the new location of Savannah and told him that it was the burial site of an ancestral chief who had many years before entertained European visitors. The leader of the European explorers had a red beard. They traveled up the Savannah River in a barge.

This description sounds like Captain Jean Ribaut’s visit to Chikola in 1562. 6 Captain René de Laudonnière, commander of Fort Caroline, later wrote that Chicola (Chikola) was one and the same as the Province of Chicora, described by Spanish explorers in 1521.

Both Chikili and Tamachichi also referred to a large mound at the southeast edge of Savannah that was the burial place of the first “Creek Emperor.” 7 This large mound was labeled prominently on a map of Savannah County, produced in Germany in 1735.

- Introduction to the Migration Legend of the Creek People

- Gatschet’s Translation of the Migration Legend of the Creek People

- Thornton’s Translation of the Migration Legend of the Creek People

- Modern Translation of the Migration Legend of the Creek People (with annotations)

Citations:

- Thornton, Richard L.. “Original Migration Legend discovered.” http://peopleofonefire.com/news-flash-original-copy-of-the-migration-legend-of-the-creek-people-rediscovered.html June 1, 2015.[

]

- History Channel, “America Unearthed.” Season 1, Episode 1, “The Georgia-Mayan Connection.”[

]

- “An eyewitness account of the Green Corn Festival.” http://peopleofonefire.com/boosketau.html Aug.14, 2015.[

]

- Christie, Thomas (1735) The original Migration Legend of the Creek People.”[

]

- Jones Charles C. (1873) Antiquities of the Southern Indians, Particularly the Georgia Tribes. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press; p, 131.[

]

- Bennett, Charles. (2000) Three Voyages. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press; pp. 29-30.[

]

- Christie, Thomas (probably) “An eyewitness account of the Green Corn Festival.”[

]