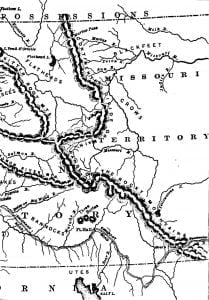

We will now leave New Mexico for a time and see what is being done in Oregon. As we make this change of position let as examine the country and its inhabitants, in a general way. Suppose we can rise in the air to a convenient height and take a bird’s-eye view of the entire region. We are now over the southeastern corner of the mountain country. Directly north from as runs the great continental divide, until it reaches about the 48th parallel of latitude, just west of the site of the future city of Cheyenne; there it turns to the left and trends northwest to our boundary. The foothills, which occupy only a narrow strip of country between the main range and the plains as far north as parallel 41, bear gradually to the east above that point, thus leaving a great triangular body of comparatively low mountain land, east of the continental divide, for the northeastern corner of our region. It will eventually form Western Dakota and nearly all of Wyoming and Montana. West of the divide the country is separated into four great natural divisions. The farthest from us is the immediate slope of the Pacific, cut off from the great central basins by the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountain ranges, which follow the general contour of the coastline. This division will hereafter make California and the western parts of Oregon and Washington Territory. At about parallel 42 of north latitude we see an immense, transverse watershed crossing the central mountain region from the Rockies to the Sierra Nevada. To the north of it the country is drained by the tributaries of the Columbia, a noble stream, which breaks its way through the Cascade Mountains and flows to the Pacific. Idaho, with the eastern parts of Oregon and Washington Territory, will be carved from this section. On the south side of the transverse watershed lie the great Utah basin and the valleys of the headwaters of the Rio Colorado, separated by the Wahsatch Mountains at about longitude 111° west of Greenwich (the western line of Wyoming) as far south as 37° of north latitude, where this watershed turns to the west at a right angle and continues to the Sierra Nevada. The Utah basin includes the future state of Nevada and western Utah. The land drained by the Colorado system will be known after some years as Eastern Utah, Western Colorado, and Arizona. The artificial divisions of the mountain country, as we look at it, are very simple. All the country east of the divide is embraced in Missouri Territory and New Mexico, which are separated by the Arkansas River. West of the divide likewise there are two sections, Oregon and Upper California, separated by parallel 42 of north latitude.

There are few whites in the country as yet. There is a little settlement at Pueblo, on the Arkansas, a considerable colony of Mormons southeast of the Great Salt Lake, and a few ranches in California. Aside from the scattered forts and trading posts, we see no more establishments of white men except in Oregon, where they are almost wholly west of the Cascade Range. The natives find their tribal boundaries to a large extent in the natural ones mentioned above. On the neighboring plains to the east of us are the Kiowas and Comanches. North of them, on the plains near the mountains, are the Cheyennes and Arapahoes, ranging from the Arkansas to the Platte. To the north again, along the border of the foothills, is the numerous Sioux or Dakota family, extending to our northern boundary and far to the east. Parts of the great northeastern triangle are inhabited by the Crows and the Assinaboines, who are of the Dakota family; the Blackfeet, who, like the Cheyennes, are a branch of the great Algonquin family of the East; and the confederated Minnetarees or Hidatsa, Ricarees (Arikaras, Rees) or Black Pawnees, and Mandans, the latter a strange tribe, believed by many to be descendants of Madoc’s Welsh colony of the twelfth century. The southeastern part of the triangle is a common battleground for the surrounding tribes, who, though nearly all related, are hostile – a veritable dark and bloody ground, over which the besom of destruction swept again and again both before and after the whites entered it. On the Pacific coast the principal families are the Chinooks and Nasquallas, of Oregon, and the California Indians. From the Rio Colorado to our point of observation, the Pima nation dwells, and the tribes of Apaches and Navahos, whose language identifies them with the extensive Athabascan family of British America. In the lapse of years they, as well as the Umpquas of western Oregon, have been separated from their northern brethren, and are also much changed in character, our New Mexican neighbors being very demons in their daring and fierceness, while the Tinné, or northern Athabascans, are mild and timid. Nearly all the remainder of the mountains is held by the great Shoshonee stock, which includes many tribes. Of these the Shoshonees proper, or Snakes, live on the Snake River, south of the Salmon Mountains; the Bannocks (Bonacks, Panocks) south of the Snakes, on the same stream; and the various tribes of the Utahs (Youtas, Ewtaws, or Utes) hold the Utah basin and the headwaters of the Colorado. The Modocs of Southwestern Oregon are related to them, as are also the Kiowas and Comanches. These latter tribes have separated from their relatives over the most natural roadway across the mountains, southeast from The Dalles of the Columbia to the South Pass. (It now forms the route of a proposed railway to connect Oregon with the Gulf of Mexico, the building of which is only a question of time.) It is the same road that Dr. Whitman followed with his emigrants. We will follow it into his missionary field of Eastern Oregon, the only part of the central region not occupied by the Shoshonees.

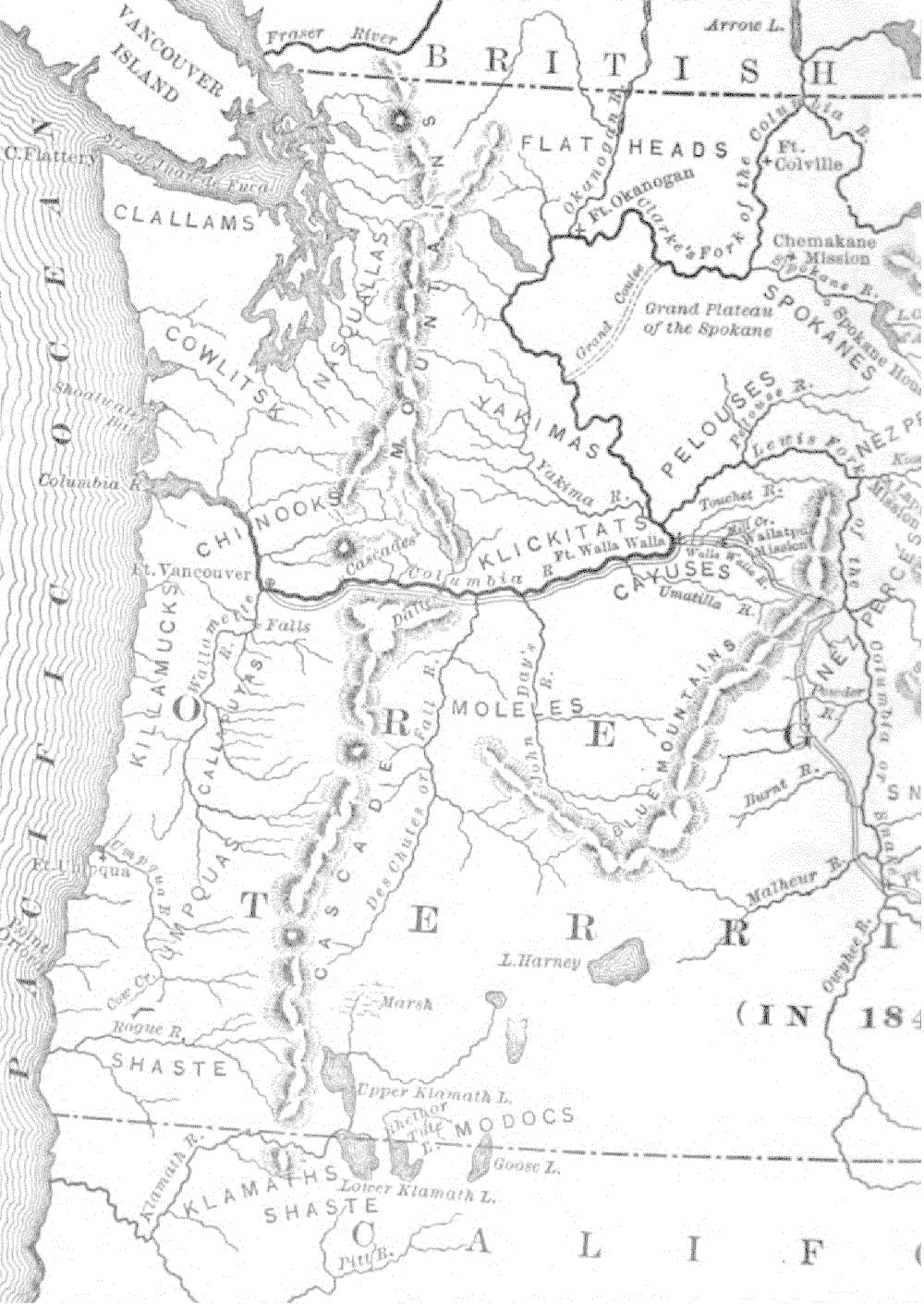

We find Eastern Oregon subdivided in two parts by the Blue and the Salmon Mountains, really one range, which is cut by the Lewis or Snake River. These mountains form the northern limits of the Shoshonees, except that the lower Nez Perce own the country as far south as the Powder River. At present, however, they are across the mountains, with their brethren, receiving “The Book” from Mr. Spalding. North and west of these mountains is the mission field, in which there are three principal Indian families. Nearest the British possessions is the Selish (Salish, Saalis) or Flathead family, including the Flatheads proper (to whom belong the Spokanes), the Coeur d’Alenes (Pointed Hearts or Skitsuish), the Kalispels (Pend d’Oreilles), and some small tribes grouped about forts Colville and Okanogan. None of these Indians practice flattening the head, as their name would imply; that is a custom confined to the tribes of the Lower Columbia and ‘ the coast, and by them allowed only to the higher classes.1

To the south of the Selish is the Sahaptin or Saptin family, including the Nez Perce and the WallaWallas, the latter embracing the Klickitats (Tlickitacks), Des Chutes, Yakimas, and Pelouse (Palus, Paloose). Still south, below the Columbia, is the Wailatpu family, including the Cayuses (Kayonse, Cailloux, Caagnas, Skyuse2) and the Moleles (Mollallas), a proud and insolent people, quite wealthy, especially in horses.3

We follow the emigrants’ road through the Grande Ronde, over the Blue Mountains and down Walla Walla Creek. The first white settlement we find is the mission at Wailatpu (the Place of Wild Rye), the home of Dr. Whitman, close by the village of the Cayuse chief Tilokaikt (Crawfish that Walks Forward). The establishment and its surroundings indicate peace and prosperity. It covers a triangular piece of ground of about four hundred feet to the side, in a bit of bottomland between Mill Creek and Walla Walla Creek. The wooden building at the southern apex is the mill. The rest of the buildings, along the northern line, are in order, at the east a story and a half house, called the mansion; eighty yards west, the blacksmith shop; at the end of the line, the doctor’s house, fronting west. This last is quite commodious. The main building is 18 X 62 feet, with adobe walls. At the south end is the library and bedroom; in the middle the dining and sitting room, 18 X 24; on the north end the Indian room, 18 x 26. Joining the house on the east is the kitchen, 18 x 26, with fireplace in the centre and bedroom in the rear. Joining the kitchen on the east is the schoolroom, 18 x 30. On the southeastern side of the mission are the millpond and Walla Walla Creek. Along the north side runs the wastewater ditch from the mill, which also serves for irrigating.

The mission has no immediate white neighbors. Twenty-five miles west, at the mouth of the creek, is Fort Walla Walla, a Hudson’s Bay Company’s post (present village of Wallula). It is a strong looking stockade, built of driftwood taken from the Columbia, with log bastions at the northeast and southwest corners, each provided with two light cannon and small arms. Down the Columbia, at the Dalles, is the nearest of the original Methodist missions, lately transferred to the American Board, and others are west of the Cascade range, especially in the Willamette or Wallamet Valley, where most of the pioneer settlers have established themselves. On the north side of the Columbia, just above the mouth of the Wallamet, is Fort Vancouver, headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company, a substantial stockade enclosing two acres of land, with hewn timber houses, well armed and manned. One hundred and twenty miles northeast of Wailatpu, where Lapwai Creek debouches into the Kooskoosky or Clearwater River, Mr. Spalding and wife are laboring successfully with the Nez Perce. Away to the north, near the Spokane River, sixty five miles south of Fort Colville, is Cimiakin (Chemakane, Ishimikane), another mission of the American Board, where Messrs. Walker and Eells, with their helpers, are making lasting conversions.

In order to understand the real condition of affairs which exists under the seeming peaceful exterior of the country, we must go back a little. Whitman’s missionary party had been kindly received by the officials of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and, having been put on their guard as to its designs, they remained on friendly terms for some years. But a time came at length when they were forced to go in opposition to it, or throw away all patriotism, and they took the former course, as we have seen. The company realized that its control of the fur trade and of the country in general, depended on England’s retaining its sovereignty. It desired England to retain control, simply because it would make more money in that event. To maintain the immense profits which they reaped from the trade, its managers used every means, fair and foul. They gave the Indians rum, because it was a profitable commodity. They countenanced and maintained Indian slavery, because it gave control over the natives. They strenuously opposed agriculture, even by British missionaries, because agriculture spoiled good hunting grounds, and, if learned by the Indians, would giv6 them an easier mode of support than hunting. They paid the Indians very little for furs, and allowed no one to pay more than their established “tariff.” They sold the Indians guns and ammunition, because it made their hunting more successful. When it became evident that the Americans were forcing the settlement of the country, the company fought every step of their progress, and yet reaped the advantages of civilization as well as savagery. At first it owned nearly all the cattle in the country, and would let the settles have them only on terms that they and all their increase should belong to the company, subject to its recall at any time; and, if they died, to be paid for by the borrower. In order to obtain cattle of their own, the Methodist missionaries, with Mr. Ewing Young (one of the party brought into Oregon by Hall J. Kelly), organized the Wallamet Cattle Company, and brought in stock from California. As soon as they got their cattle in, the Hudson’s Bay Company organized the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, which was maintained out of the fund established by the corporation for the purpose of fighting hostile interests, and began selling cattle lower than the other company could. In 1842 the American settlers, with great difficulty, succeeded in getting a mill started at the falls of the Wallamet. The company at once put up an opposition saw and grist mill at the same place. Some parties settled at those falls, and forthwith Dr. McLaughlin, chief factor of the company, claimed the land as his, warned the trespassers off, and laid off the town site of Oregon City.

Dr. McLaughlin, however, had too much conscience for ‘ the company. He had, indeed, carried out their instructions up to this point, but they desired him to go further. They insisted that he must no longer furnish supplies on credit to needy American settlers, and he, after explaining to them that he could not, in common humanity, obey them, told the directors: ” If such is your order, gentlemen,! will serve you no longer.” He served them no longer, and his place was filled by James Douglass (afterwards Sir James), who was more complaisant. About the same time McKinley, their factor at Fort Walla Walla, who was a little friendly with the Americans, was removed, and his place filled by one McBean, who proved thoroughly reliable, from a company standpoint. By misrepresentations American immigrants were prevented from bringing their wagons farther than Fort Hall, until Dr. Whitman broke their blockade in 1843, and after that Captain Grant, the factor at that place, and others, used all their powers of persuasion to turn the immigration into California. Among those, it is claimed; whom they succeeded in turning into those then unknown deserts was the Donner party, whose frightful sufferings and enforced cannibalism have since furnished a theme of horror to many writers. At the same time Sir George Simpson, at Washington, and other emissaries elsewhere, were representing to our government the desert nature of the country and slandering our settlers. In short, they tried to do in Oregon what they had done in British America, where, by an English authority, they “hold a monopoly in commerce and exercise despotism in government; and have so used that monopoly and wielded that power as to shut up the earth from the knowledge of man, and man from the knowledge of God.” From these facts it is only a fair inference that the Jesuit priests, who came into Oregon in 1838, were brought there by the Hudson’s Bay Company to counteract the effect of the Protestant missions. Certain it is that the Jesuits came under their convoy, and from first to last, received such sympathy and assistance as no Protestant missionary, British or American, ever received at their hands.

The motives of the Jesuits need not be questioned. Father De Smet probably states them truly in a letter written to their Belgian friends for further assistance. He says: “Time passes; already the sectaries of various shades are preparing to penetrate more deeply into the desert, and will wrest from those degraded and unhappy tribes their last hope – that of knowing and practicing the sole and true faith.” Aside from this apprehension of heresy, there was no need of their concentrating on Oregon. If they were merely solicitous for the eternal welfare of Indians, there were thousands of them elsewhere to whom no missionary had yet spoken. The fact cannot be evaded that they made their war on Protestantism, not heathenism. The results of their labors might reasonably have been anticipated. In a short time the simple natives were involved in the same sectarian controversy that had deluged all Europe in blood. The priests told the Indians that if they followed the teachings of the Protestants they would go to hell. The Protestants extended the same cheering information in regard to Catholicism. The priests used, in teaching, a colored design of a tree surmounted by a cross, and called “the Catholic tree.” It showed the Protestants continually going out on the limbs and falling from their ends into tires, which were fed with Protestant books by the priests, while the Catholics were safely climbing the trunk to the emblem of salvation above. Mr. Spalding was equal to the emergency. He had his wife paint a series of Bible pictures in watercolors, the last and crowning one of which showed the ” broad way that leadeth to destruction,” crowded with priests, who were tumbling into hell at the terminus, while the Protestants ascended the narrow path to glory. The Indians became divided among themselves, and bitter controversies became common. The priests gained steadily. Churches, nunneries, and schools sprang up at French Prairie, Oregon City, Vancouver, The Dalles, Umatilla, Pend d’Oreille, Colville, and Ste. Marie. They had potent allies in the French Canadian interpreters and other employees of the company. When the Indians appealed to these to know which was the true religion, they were informed that the priests had the genuine article. So it went on until the Indians were in a fit state of mind for the crime which followed. They became restless and turbulent. Some of the Protestant missionaries left the country. Even the indomitable Dr. Whitman called his Cayuses together several times, and told them he would leave whenever a majority of them said he should, but the majority remained with him.

In the summer of 1847 the newly appointed Jesuit Bishop of Oregon, F. N. Blanchet, returned with a reinforcement of thirteen clergymen, of different ranks, and seven nuns; eight priests and two nuns also arrived overland the same season. The bishop proceeded up the river, and on September 5 reached Fort WallaWalla, accompanied by the superior of Oblates and two other clergymen. On September 23 he was met there by Dr. Whitman, who, according to Father Brouillet, showed that he was agitated and wounded by the bishops’ arrival. He said: “I know very well for what purpose you have come.” The bishop replied: “All is known. I come to labor for the conversion of the Indians, and even of the Americans, if they are willing to listen to me.” The bishop and his party remained at the fort enjoying the hospitality of the company. On October 26, Ta-wai-tau (Young Chief), a Catholic Cayuse chief, arrived and held a conference with the bishop. On November 4 a general council was held, at which Tilokaikt, who owned the land on which Whitman’s mission stood was present. The Protestants say the Indians were given to understand that the priests would like to have Whitman’s place; the Jesuits say it was offered to them and they refused to take it. On November 27 the bishop and party left for the Umatilla, a few miles below, to occupy a house offered them by Young Chief at his and Five Crows’ village, which was twenty-five miles southwest of Wailatpu.

Two days have passed. It is half-past one o’clock of Monday, November 29. Nothing appears to mar the usual quiet which prevails at the Wailatpu mission. The only sounds distinguishable are the rumbling of the mill, where Mr. Marsh is grinding, and the tapping of a hammer in one of the rooms of the doctor’s house, where Mr. Hall is laying a floor. There is, too, the low hum of the school, which Mr. Sanders has just called for the afternoon. Between the buildings, near the ditch, Kimball, Hoffman, and Canfield are dressing an ox. Gillan, the tailor, is on his bench in the mansion. Mr. Rogers is in the garden. In the blacksmith’s shop, where Canfield’s family lives, young Amos Sales is lying sick. Crockett Bewley, another young man, is sick at the doctor’s house. The Sager boys, orphans of some unfortunate emigrants, who with their younger sisters had been adopted by the doctor, arc scattered about the place. John, who is just recovering from the measles, is in the kitchen, Francis in the schoolroom, and Edward outside. In the dining room are Dr. Whitman, Mrs. Whitman, three of the little Sager girls – all sick – Mrs. Osborne, and her sick child. As the doctor reads from the Bible several Indians open the door from the kitchen and ask him to come out. He goes, Bible in hand, closes the door after him, sits down, and Tilokaikt begins talking to him. As they converse, Tamsaky (Tumsuckee) steps carelessly behind the doctor and the other Indians gather about, seeming much interested. Suddenly Tamsaky draws a pipe tomahawk from beneath his blanket, and strikes the doctor on the head. His head sinks on his breast, and another blow, quickly following, stretches him senseless on the floor. John Sager jumps up and draws a pistol. The Indians in front of him crowd back in terror to the door, crying, “He will shoot us,” but those behind seize him and throw him to the floor. At the same time knives, tomahawks, pistols, and short Hudson’s Bay Company muskets flash from beneath their blankets, and John is shot and gashed until he is senseless. His throat is cut, and a woollen tippet is stuffed in the wound. With demoniac yells the Indians rush outside to join in the work there. The sounds of the deadly struggle are heard in the dining room. Mrs. Whitman starts up and wrings her hands in agony, crying, “Oh, the Indians, the Indians! That Joe (meaning Joe Lewis) has done it all.” Mrs. Osborne runs into the Indian room with her child, and they, with Mr. Osborne, are soon secreted under the floor. Mrs. Hall comes screaming into the dining room, from the mansion. With her help, Mrs. Whitman draws the doctor into that room, places his head on a pillow, and tries to revive him. In vain! he is unconscious, and past all help. To every loving word and sympathetic question he faintly whispers,” No.”

Outside is a scene of wild confusion. At the agreed signal all the members of the mission had been attacked. Gillan was shot on his bench; Marsh was shot at the mill; he ran a few yards towards the house and fell. Sanders had hurried to the door of the schoolroom, where he was seized by a crowd of Indians, thrown to the ground, shot, and wounded with tomahawks. Being a powerful man, he threw off his assailants, regained his feet, and tried to run away, but was overtaken and cut down. Hall snatched a loaded gun from an Indian and escaped to the bushes. The men working at the ox received a volley from pistols and guns, which wounded them all, but not mortally. Kimball fled to the doctor’s house, with a broken arm. Canfield escaped to the mansion, where he hid until night. Hoffman lunged desperately among the Indians with his butcher knife, but was soon cut down; his body was ripped open and his vitals torn out. Rogers was shot in the arm, and wounded on the head with a tomahawk, but managed to get into the doctor’s house. Several women and children have fled in the same direction. To this place, the Indians, who have been running to and fro, howling wildly as they pursued their prey, now assemble, led by Joe Lewis and Nicholas Finlay, French half-breeds, Tamsaky and his son Waiecat, Tilokaikt and his sons Edward and Clark. Joe Lewis enters the schoolroom and brings into the kitchen the children, who had hid in the loft. Among them is Francis Sager, who, as he passes his brother John, kneels and takes the bloody tippet from his throat. John attempts to speak, but in the effort only gasps and dies. The trembling children remain huddled together, surrounded by the savages, who point their guns at them and constantly cry, “Shall we shoot?” On the other side of the house an Indian approaches the window, and shoots Mrs. Whitman in the breast. She falls, but creeps to the sofa, and her voice rises in prayer for her adopted children and her aged father and mother. The fugitives upstairs hear her and help her up to them. There are now gathered in that upper chamber Mrs. Hays, Mrs. Whitman, Miss Bewley, Catharine Sager and her three sick sisters, three half-breed girls, also sick, Mr. Kimball, and Mr. Rogers. Hardly have they closed and fastened the doors, when the war whoop sounds below; the Indians break in the lower doors and windows and begin plundering, while Tilokaikt goes to the doctor, who still breathes, and chops his face to shreds with his tomahawk.

The people upstairs have found an old gun, and the Indians, as they start to go up, find it pointed in their faces. They retire in great alarm. A parley is held, and Tamsaky goes up. He assures the fugitives that he is sorry for what has been done, and advises them to come down, as the young men are about to burn the house. He promises them safety. They do not know of his part in the tragedy, and follow him. As they enter the dining room Mrs. Whitman catches sight of the doctor’s mangled face. She becomes faint, and is placed on the sofa. They pass on through the kitchen, Mrs. Whitman being carried on the sofa by Joe Lewis and Mr. Rogers. As they reach the outside Lewis drops his end of the sofa and the Indians fire their guns. Mr. Rogers throws up his hands, cries, “Oh, my God, save me!” and falls groaning to the earth. Mrs. Whitman receives two balls and expires. The Indians spring forward, strike her in the face, and roll her body into the mud. They heighten the terror of the wretched survivors by their terrible yelling, and the brandishing of their weapons. Miss Bewley runs away, but is overtaken and led over to the mansion. Mr. Kimball and the Sager girls run back through the house and regain the chamber, where they remain all night. Darkness has now come on, and the Indians, having finished their plundering, and perpetrated their customary indignities on the dead, retire to Finlay’s and Tilokaikt’s lodges to consult on their future action. The first and great day of blood is ended.

It may easily be imagined that the night was one of gloom and horror to the unfortunate captives, and yet it afforded security to some of those who were in peril. Under its friendly cover Mr. Canfield escaped and made some progress towards Lapwai, which he eventually reached in safety. Mr. Osborne, with his family, stole forth from their place of concealment under the doctor’s house, and reached Fort WallaWalla on the following day. Mr. Hall reached the same place early in the morning, nearly naked, wounded, and exhausted. He was put across the river by McBean, the factor, and was never heard of afterwards. It is probable that information of the massacre was sent that night to the other Cayuse villages, Camaspelo’s and the one on the Umatilla. The other chiefs were consulted before the affair occurred, and Five Crows (called by the whites Hezekiah, which Brouillet mistakes for Achekaia) was then head chief of the tribe. On the next day Mr. Kimball was shot as he went from his concealment in the chamber for water for himself and the sick children. The young Indian who shot him afterwards claimed his eldest daughter for a wife, as a recompense for this murder. On the same day they killed Mr. Young, a young man who had come up from the saw mill, twenty miles away. In the evening Vicar-general Brouillet arrived. On Wednesday Brouillet and Joseph Stanfield buried the victims. This Stanfield was a French Catholic who had been employed at the mission, and was without doubt deeply implicated in the massacre, though he escaped conviction. Later in the day, Brouillet, having made a sympathetic call on the widows and orphans, returned to the Umatilla. On the way he met Mr. Spalding and notified him of the massacre. Spalding struck off into the woods and reached Lapwai, after six days of terrible exposure and suffering, without shoes, blanket, or horse. On Saturday night, and repeatedly afterwards, the three oldest of the girls were dragged out and outraged. On the Monday following, young Bewley and Sales were murdered. On Thursday Miss Bewley was taken to the Umatilla and turned over to the tender mercies of Five Crows. At the same time the other two of the older girls were taken as wives by the sons of Tilokaikt (called Edward and Clark Tilokaikt by the whites), in pursuance of an agreement which had been made at the Umatilla. One of these young braves, whose Indian name was Shumahiccie (Painted Shirt), became very much attached to his enforced bride, a beautiful girl of fourteen, and wanted her to remain with him when the other captives were surrendered. He said he was a great brave and owned many cattle and horses; he would give them all to her, or, if she did not like his people, he would forsake them and live with the pale faces. But he pleaded in a hopeless cause. His hands were stained with the blood of her elder brother, and she had lived with him until that time only because he had threatened to kill her younger sisters if she did not.

The news of the massacre reached the settlements west of the mountains on December 7, by a messenger of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Mr. Ogden, of the company, at once started for Fort Walla Walla, and on December 23, by his efforts, an arrangement was effected for the surrender of all the captives, in exchange for a considerable amount of goods, including guns and ammunition. On December 29 the captives at Wailatpu, forty-six in number, arrived at the fort. On January 1, Mr. Spalding and wife, with the other whites from Lapwai, came in. The Nez Perces offered to protect them and the mission, if they would remain, but affairs were so unsettled, and Mr. and Mrs. Spalding were in such anxiety for their daughter that they decided to leave. All of these, together with the live fugitives already at the fort, started down the river on January 2, and arrived in safety below.

On December 8, Governor Abernethy had convened the provisional legislature at Oregon City and prepared at once for a levy of troops. A company of forty-two men was organized, and started within twenty four hours, and Captain Lee with ten of the men reached The Dalles on the 21st. This being the last settlement on the river, below the missions, and the families having gone below, the volunteers remained for a time to protect the houses. When the captives were brought down the river there was no further call for their immediate presence above, so they remained there until the last of the reinforcements, under Colonel Gilliam, arrived, on February 23. Captain Lee was then sent on a scouting expedition among the Des Chutes, who were the nearest hostiles. He found them on the 28th, and a skirmish ensued in which half a dozen Indians were killed, with no loss to the whites. The main body, 160 men, then moved towards Wailatpu. On the 30th they were attacked by an equal number of Indians, who were driven back with a loss of twenty men, forty horses, and a large amount of goods. A few days later an attempt was made, under pretence of treating for peace, to entrap them on the prairie between Mud Spring and Umatilla, by about 500 Indians, under Nicholas Finlay, the Wailatpu murderer, but the troops formed a hollow square and continued their march, very little damage being done on either side. They reached Wailatpu, established Fort Waters at that point, and held a talk with the friendly Indians who came in, mostly Nez Perce, including Camaspelo, of the Cayuses. Their words were all to the effect that they were not implicated in the massacre and would not protect the murderers. One of the speeches was by Joseph, chief of the lower Nez Perces and half-brother to Five Crows. We shall have occasion to speak of him hereafter. He said: “Now I show my heart. When I left my home I took the Book (a Testament given him by Mr. Spalding) in my hand and brought it with me; it is my light. I heard the Americans were coming to kill me. Still I held my Book before me and came on. I have heard the words of your chief. I speak for all the Cayuses present and all my people. I do not wish my children engaged in this war, although my brother (Five Crows) is wounded. You speak of the murderers; I shall not meddle with them; I bow my head; this much I speak.’*

As the troops advanced into their country, part of the hostile Cayuses retired into the neighboring mountains; the remainder fell back on the country of the Nez Perces. The troops, after several skirmishes, succeeded in driving them across the divide, and capturing their horses and cattle to the number of 500 or more, but the Indians escaped. Small garrisons were kept at Fort Waters and The Dalles until September, 1848, and the tribes of the murderers, not daring to return to their old homes, were forced to pursue a wandering life among the mountains. In the spring of 1850 they purchased peace by surrendering five of the leading offenders, including Tilokaikt and Tamsaky, all of whom were tried, convicted, and, on June 3 of the same year, hung at Oregon City. They all embraced the Catholic faith, and were baptized by Bishop Blanchet a few hours before their death.

The buildings at Wailatpu were all burned by the Indians, and today their places are marked by mounds of earth, into which the adobe walls sank as the elements wore upon them, except that on the site of the doctor’s house a residence was afterwards erected by an old friend and co-laborer of his. A few rods away, on a hillside, is the common grave of the victims. The visitor who runs over to the site of the mission, from the little town of Walla Walla, finds still, as living remembrances of those Christian pioneers, two or three weather beaten apple trees and a rank growth of scarlet poppies, which have run wild from the old garden.

- See Further: No Catholics were Injured during Massacre