The events of which we shall now proceed to give a brief synopsis, were of more momentous interest, and fraught with more deadly peril to the New England colonies, than aught that had preceded them. The wild inhabitants of the forest had now become far more dangerous opponents than when they relied upon their rude flint-headed arrows, or heavy stone tomahawks, as the only efficient weapons of offense. Governor Bradford, many years before the breaking out of the hostilities which we are about to detail, had given a graphic description of the effect produced upon their deportment and self-confidence by the introduction of European weapons. We quote from Bradford s verse, as rendered in prose in the appendix to Davis edition of the New England Memorial.

“These fierce natives,” says he, “are now so furnished with guns and muskets, and are so skilled in them, that they keep the English in awe, and give the law to them when they please; and of powder and shot they have such abundance that sometimes they refuse to buy more. Flints, screw-plates, and moulds for all sorts of shot they have, and skill how to use them. They can mend and new stock their pieces as well, almost, as an Englishman.”

He describes the advantages which they thus obtained over the whites in the pursuit of game; their own consciousness of power, and boasts that they could, when they pleased, “drive away the English, or kill them;” and finally breaks out into bitter upbraiding against the folly and covetousness of the traders who had supplied them with arms. His forebodings were truly prophetic: “Many,” says he, “abhor this practice,” (the trade in arms and ammunition,) “whose innocence will not save them if, which God forbid, they should come to see, by this means, some sad tragedy, when these heathen, in their fury, shall cruelly shed our innocent blood.”

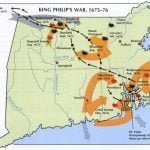

Situation Of The Colonists

The English settlements were small, ill defended, and widely scattered. Whoever is acquainted with the rough nature of the New England soil, must at once perceive how necessary it became for the first settlers to select the spots most favorable for cultivation, and what an inhospitable wilderness must have separated their small and ill-protected villages.

The whole number of the European inhabitants of New England, in 1675, when the memorable Indian war broke out, has been computed at about fifty thousand, which would give an effective force of not far from eight thousand men.

It were but wild conjecture to attempt a computation of the number and force of the native tribes who took part in the war. Old historians frequently speak positively, and in round numbers, when enumerating the aborigines; but, in many instances, we can perceive, with tolerable certainty, that they have been guilty of gross exaggeration, such as the whole circumstances of their intercourse with the savages would naturally lead to.

An enemy whose appearance was sudden and unexpected; who, in secret ambuscade or midnight assault, used every device to increase the terror and bewilderment of their victims, might well be over-estimated by those whose all was at stake, and who were waiting in fearful uncertainty as to where the danger lay, or when they should next be called to resist it.

Philip’s Accession

In 1662, Philip, Metacomet, or Pometacom, as we have already seen, succeeded his brother Alexander, within a few months of the death of their father, Massasoit. Upon the occasion of his assuming the dignity of sachem over the Wampanoags, there was a great collection of sachems and warriors from all parts of the country, to unite in a feast of rejoicing at Mount Hope, where he held his court.

Although the new chief renewed his treaty with the English, and for nine years after his accession made no open demonstrations of hostility, yet his mind appears from the first to have been aliened from the intruders. Whether from anger at the proceedings attendant on the death of his brother, or from sympathy with his injured allies, the Narragansetts, or that his natural sagacity suggested to him the ruin which must fall upon his people by the spread of the whites; certain it is that his feelings of enmity were nourished and brooded over, long before their final exhibition.

Like his father before him, he never inclined an ear to the teachings of the Christian religion. Mather mentions a signal instance of his contempt for this species of instruction. The celebrated preacher, Eliot, had expounded the doctrines of Christianity, and urged their acceptance upon Philip, with his usual zeal and sincerity; but the sachem, approaching him, and laying hold of a button on his coat, told him that he cared no more for his Gospel than for that button.

In the year 1671, Philip made grievous complaints of trespasses upon the planting-lands of his people: according to Hubbard, “the devil, who was a murderer from the be ginning, had so filled the heart of this savage miscreant with envy and malice against the English, that he was ready to break out into open war against the inhabitants of Plymouth, pretending some trifling injuries done him in his planting-land.”

This matter was for the time settled, the complaints not appearing to the colonial authorities to be satisfactorily substantiated. A meeting was brought about, in April, 1671, at Taunton, between Philip, accompanied by a party of his warriors, in war paint and hostile trappings, and commissioners from Massachusetts. The Indian chief, unable to account for the hostile preparations in which he was proved to have been engaged, became confused, and perhaps intimidated. He not only acknowledged himself in the wrong, and that the rebellion originated in the “naughtiness of his own heart,” but renewed his submission to the king of England, and agreed to surrender all his English arms to the government of New Plymouth, “to be kept as long as they should see reason.” In pursuance of this clause, the guns brought by himself and the party who were with him were delivered up.

The colonists, now thoroughly alarmed, made efforts during the succeeding summer to deprive the neighboring tribes of arms and ammunition, making further prohibitory enactments as to the trade in these articles. Philip having failed to carry out his agreement to surrender his weapons, the Plymouth government referred the matter to the authorities of Massachusetts; but Philip, repairing himself to Boston, excited some feeling in his favor, and the claims of Plymouth were not fully assented to. Another treaty was concluded in the ensuing September, whereby Philip agreed to pay certain stipulated costs; to consider himself subject to the king of England; to consult the governor of Plymouth in the disposal of his lands, as also in the making of war; to render, if practicable, five wolves heads yearly; and to refer all differences and causes of quarrel to the decision of the governor. The arms put in possession of the English at the time of the meeting in April, were declared forfeit, and confiscated by the Plymouth government.

His True Plans

There can be but little doubt as to Philip’s motive for signing these articles. Feelings of enmity and revenge towards the whites had obtained complete possession of him, and he evidently wished merely to quiet suspicion and avert inquiry. It is almost universally allowed that he had long formed a deep and settled plan to exterminate the white settlers, and, in pursuance of it, had made use of all his powers of artful persuasion in his intercourse with the surrounding tribes. The time for a general uprising was said to have been fixed a year later than the period when hostilities actually commenced, and the premature development of the conspiracy, brought about in a manner to which we shall presently advert, has been considered the salvation of the colonies.

Hubbard, indeed, who is ever unwilling to allow that the Indians were possessed of any good or desirable qualities, and who can see no wrong in any of the outrages of the whites, suggests that Philip s heart would have failed him, had he not been pressed on to the undertaking by force of circumstances. He tells us that, when the great sachem succumbed to the English demands, in the spring previous, “one of his captains, of far better courage and resolution than himself, when he saw his cowardly temper and disposition, flung down his arms, calling him a white livered cur, or to that purpose, and saying that he would never own him again or fight under him; and, from that time, hath turned to the English, and hath continued, to this day, a faithful and resolute soldier in their quarrel.”

Philip had mingled much with the whites, and was well acquainted with their habits, dispositions, and force. For fifty years there had been comparative peace between the colonists and their savage neighbors, who, although slow to adopt the customs and refinements now brought to their notice, were apt enough, as we have seen, in availing them selves of the weapons which put the contending nations so nearly upon terms of equality.

To rouse a widely-scattered people to such a desperate struggle; to reconcile clannish animosities, and to point out the danger of allowing the colonies to continue their spread, required a master-spirit. The Wampanoag sachem proved himself qualified for the undertaking: he gained the concurrence and cooperation of the Narragansetts, a nation always more favorably disposed towards the English than most others of the Indian tribes; he extended his league far to the westward, among the tribes on the Connecticut and elsewhere; and sent diplomatic embassies in every direction.

Emissaries Sent To Sogkonate

Six of his warriors, in the spring of 1675, were dispatched to Sogkonate, now Little Compton, upon the eastern shores of Narragansett bay, and extending along the sea-coast, to treat with Awoshonks, squaw sachem of the tribe, concerning the proposed uprising. The queen appointed a great dance, calling together all her people, but, at the same time, took the precaution to send intelligence of the proceeding, by two Indians, named Sassamon and George, who understood English, to her friend, Captain Benjamin Church, the only white settler then residing in that part of the country.

This remarkable man, whose name occupies so prominent a place in the list of our early military heroes, had moved from Duxbury into the unsettled country of the Sogkonates only the year before, and was busily and laboriously engaged, at this time, in building, and in the numerous cares attendant upon a new settlement. He was a man of courage and fortitude unsurpassed: bold and energetic; but with all the rough qualities of a soldier, possessing a heart so open to kindly emotions and the gentler feelings of humanity as to excite our surprise, when we consider the stern age in which he lived, and the scenes of savage conflict in which he bore so conspicuous a part.

True courage is generally combined with generosity and magnanimity. The brave man seldom oppresses a fallen foe; a fact strikingly exemplified in Church’s treatment of his prisoners. He seems to have harbored none of those feelings of bitterness and revenge, which led the colonists to acts of perfidy and cruelty hardly surpassed by the savages themselves. The manner in which he was able to conciliate the good will of the Indians, known as he was among them for their most dangerous foe, is truly astonishing. It was his custom to select from his captives such as took his fancy, and attach them to himself, and never was officer attended by a more enthusiastic and faithful guard than they proved. His son tells us that “if he perceived they looked surly, and his Indian soldiers called them treacherous dogs, as some of them would sometimes do, all the notice he would take of it would only be to clap them on the back, and tell them, Come, come, you look wild and surly, and mutter, but that signifies nothing; these, my best soldiers, were, a little while ago, as wild and surly as you are now; by the time you have been but one day with me, you will love me too, and be as brisk as any of them. And it proved so, for there was none of them but, after they had been a little while with him, and seen his behavior and how cheerful and successful his men were, would be as ready to pilot him to any place where the Indians dwelt or haunted, though their own fathers or nearest relations should be among them, or to fight for him, as any of his own men.”

Captain Church was in high favor and confidence with Awoshonks and her tribe; he therefore accepted her invitation to attend at the dance, and started for the camp, accompanied by a son of his tenant, who spoke the Indian language.