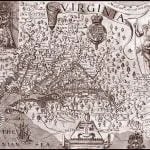

The most complete and veracious account of the manners, appearance, and history of the aboriginal inhabitants of Virginia, particularly those who dwelt in the eastern portion of that district, upon the rivers and the shores of Chesapeake Bay, is contained in the narrative of the re doubted Captain John Smith. This bold and energetic pioneer, after many “strange adventures, happened by land or sea;” still a young man, though a veteran in military service; and inured to danger and hardship, in battle and captivity among the Turks, joined his fortunes to those of Bartholomew Gosnoll and his party, who sailed from England on the 19th of December, 1606, (O. S.) to form a settlement on the Western Continent.

Former attempts to establish colonies in Virginia had terminated disastrously, from the gross incompetence, extravagant expectations, improvidence, and villainous conduct of those engaged in them.

Expedition Of Amidas and Barlow

In 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh and his associates, under a patent from Queen Elizabeth, had sent out two small vessels, commanded by Amidas and Barlow. By the circuitous route then usually adopted, the exploring party passed the “West Indies, coasted along the fragrant shores of Florida, and entered Ocrakoke Inlet in the month of July, enraptured with the rich and fruitful appearance of the country. Grapes grew to the very borders of the sea, overspreading the bushes and climbing to the tops of trees in luxurious abundance.

Their intercourse with the natives was friendly and peaceful; as they reported, “a more kind, loving people could not be.” They carried on trade and barter with Granganimeo, brother to Winginia, king of the country, and were royally entertained by his wife at the island of Roanoke.

Wingandacoa was the Indian name of the country, and, on the return of the expedition, in the ensuing September; it was called Virginia, in honor of the queen.

Of Sir Richard Grenville

Sir Richard Grenville, an associate of Raleigh, visited Virginia the next year, (1585,) and left over one hundred men to form a settlement at Roanoke. Being disappointed in their anticipations of profit, or unwilling to endure the privations attendant upon the settlement of a habitation in the wilderness, all returned within a year. A most unjustifiable outrage was committed by the English of this party, on one of their exploring expeditions. In the words of the old narrative, “At Aquascogoc the Indians stole a silver cup, wherefore we burnt the town and spoiled their corn; so returned to our fleet at Tocokon.” This act is but a fair specimen of the manner in which redress has been sought for injuries sustained at the hands of the natives, not only in early times, but too often at the present day.

It is not surprising that thereafter the Indians should have assumed a hostile attitude. Granganimeo was dead, and Winginia, who had now taken the name of Pemissapan, formed a plan to cut off these disorderly invaders of his dominions. This resulted only in some desultory skirmishing; and, a few days afterwards, the fleet of Sir Francis Drake appearing in the offing, the whole colony concluded to return to England.

Mr. Thomas Heriot, whose journal of this voyage and settlement is preserved, gives a brief account of the superstitions, customs, and manner of living which he observed among the savages. In enumerating the animals, which were used for food by the Indians, he mentions that “the savages sometimes killed a lion and ate him.” He concludes his narrative by very justly remarking, that some of the company ” showed themselves too furious in slaying some of the people in some towns upon causes that on our part might have been borne with more mildness.”

Grenville, in the following year, knowing nothing of the desertion of the settlement, took three ships over to America, well furnished for the support and relief of those whom he had left on the preceding voyage. Finding the place abandoned, he left fifty settlers to reoccupy it, and returned home. On the next arrival from England the village was again found deserted, the fort dismantled, and the plantations overgrown with weeds. The bones of one man were seen, but no other trace appeared to tell the fate of the colony. It afterwards appeared, from the narrations of the savages, that three hundred men from Aquascogoc and other Indian towns had made a descent upon the whites, and massacred the whole number.

The experiment of colonization was again tried, and again failed: of over one hundred persons, including some females, who landed, none were to be found by those who went in search of them in 1589, nor was their fate ever ascertained. It is recorded that, before the departure of the ships that brought over this colony, on the 18th of August (O. S.), the governor’s daughter, Ellinor Dare, gave birth to an infant, which was named Virginia, and was the first white child born in the country.

We now return to Gosnoll and his companions, numbering a little over one hundred, who, as we before mentioned, visited the country in 1606. They sailed from England with sealed orders, which were not to be opened until their arrival in America. Landing on Cape Henry, at the entrance of the Chesapeake, the hostile feelings of the Indians were soon made manifest; “thirty of the company recreating themselves on shore were assaulted by five savages, who hurt two of the English very dangerously.” The box containing the orders from the authorities in England being opened, Smith was found to be one of the number appointed as a council to govern the colony; but he was, at that time, in close custody, in consequence of sundry absurd and jealous suspicions which had been excited against him on the voyage, and he was therefore refused all share in the direction of the public affairs. Before the return of the ships, however, which took place in June, the weak and ill-assorted colony were glad to avail themselves of the services and counsel of the bold and persevering captain. His enemies were disgraced, and his authority was formally acknowledged. Meantime, the settlement was commenced at Jamestown, forty miles up the Powhatan, now James River. The Indians appeared friendly, and all hands fell to work at the innumerable occupations which their situation required. A few ruins, and the picturesque remains of the old brick church-tower still standing, utterly deserted amid the growth of shrubs and willows, are all that remains of the intended city.

Visit to Powhatan

Newport and Smith, with a company of twenty men, were sent to explore the upper portion of the river, and made their way to the town of Powhatan, situated upon a bluff just below the falls, and at the head of navigation the same spot afterwards chosen for the site of the capital of the state. The natives were peaceable and kind to the adventurers, receiving them with every demonstration of interest and pleasure, and rejoiced at the opportunity for traffic in beads and ornaments. As they approached Jamestown, on their return, they perceived some hostile demonstrations; and arriving there, found that seventeen men had been wounded, and that one boy had been killed by the Indians during their absence.

Wingfield, the president of the colony, had injudiciously neglected to make any secure fortifications, and the people, leaving their arms stored apart, set to work without a guard; thus giving to the lurking foe convenient opportunity for an assault.

After Captain Newport had sailed for England, the colonists, left to their own resources, were reduced to great straits and privation. Most of them were men utterly unfitted for the situation they had chosen, and unable to endure labor and hardship. Feeding upon damaged wheat, with such fish and crabs as they could catch; worn out by unaccustomed toil; unused to the climate, and ignorant of its diseases; it is matter of little wonder that fifty of the company died before the month of October.

Smith, to whom all now looked for advice, and who was virtually at the head of affairs, undertook an expedition down the river for purposes of trade. Finding that the natives “scorned him as a famished man,” derisively offering a morsel of food as the price of his arms, he adopted a very common expedient of the time, using force where courtesy availed not. After a harmless discharge of muskets, he landed and marched up to a village where much corn was stored. He would not allow his men to plunder, but awaited the expected attack of the natives. A party of sixty or seventy presently appeared, ” with a most hideous noise some black, some red, some white, some parti-colored, they came in a square order, singing and dancing out of the woods, with their Okee (which was an idol made of skins stuffed with moss, all painted and hung with chains and copper,) borne before them.” A discharge of pistol shot from the guns scattered them, and they fled, leaving their Okee. Being now ready to treat, their image was restored, and beads, copper, and hatchets were given by Smith to their full satisfaction, in return for provisions.

Improvidence and Difficulties of the Colonists

The improvident colonists, by waste and inactivity, counteracted the efforts of Smith: and Wingfield, the former president, with a number of others, formed a plan to seize the pinnace and return to England. This conspiracy was not checked without some violence and bloodshed. As the weather grew colder with the change of season, game became fat and plenty, and the Indians on Chickahamania River were found eager to trade their corn for English articles of use or ornament; so that affairs began to look more prosperous.

During the ensuing winter, Smith, with a barge and boat s crew, undertook an exploration of the sources of the Chickahamania, (Chickahominy,) which empties into James River, a few miles above Jamestown. After making his way for about fifty miles up the stream, his progress was so impeded by fallen trees and the narrowness of the channel, that he left the boat and crew in a sort of bay, and proceeded in a canoe, accompanied only by two Englishmen, and two Indian guides. The men left in charge of the boat, disregarding his orders to stay on board till his return, were set upon by a great body of the natives, and one of their number, George Cassen, was taken prisoner. Having compelled their captive to disclose the intentions and position of the captain, these savages proceeded to put him to death in a most barbarous manner, severing his limbs at the joints with shells, and burning them before his face. As they dared not attack the armed company in the boat, all hands then set out in hot pursuit of Smith, led by Opechancanough, king of Pamaunkee.

Coming upon the little party among the marshes, far up the river, they shot the two Englishmen as they were sleeping by the canoe; and, to the number of over two hundred, surrounded the gallant captain, who, accompanied by one of his guides, was out with his gun in search of game. Binding the Indian fast to his arm, with a garter, as a protection from the shafts of the enemy, Smith made such good use of his gun that he killed three of his assailants and wounded several others. The whole body stood at some distance, stricken with terror at the unwonted execution of his weapon, while he slowly retired towards the canoe. Unfortunately, attempting to cross a creek with a miry bottom, he stuck fast, together with his guide, and, becoming benumbed with cold, for the season was unusually severe, he threw away his arms, and surrendered himself prisoner.

Smith Taken Prisoner his Treatment by the Indians

Delighted with their acquisition, the savages took him to the fire, and restored animation to his limbs by warmth and friction. He immediately set himself to conciliate the king, and presenting him with an ivory pocket compass, proceeded to explain its use, together with many other scientific matters greatly beyond the comprehension of the wild creatures who gathered around him in eager and astonished admiration. Perhaps with a view of trying his courage, they presently bound him to a tree, and all made ready to let fly their arrows at him, but were stayed by a sign from the chief. They then carried him to Orapaks, where he was well fed, and treated with kindness.

When they reached the town, a strange savage dance was performed around Opechancanough and his captive, by the whole body of warriors, armed and painted; while the women and children looked on with wonder and curiosity. The gaudy color of the oil and pocones with which their bodies were covered, “made an exceeding handsome show,” and each had “his bow in his hand, and the skin of a bird with her wings abroad, dried, tied on his head, a piece of copper, a white shell, a long feather, with a small rattle growing at the tails of their snakes tied to it, or some such like toy.”

Although the Indians would not, as yet, eat with their prisoner, he was so feasted that a suspicion arose in his mind that they “would fat him to eat him. Yet, in this desperate estate, to defend him from the cold, one Mocassater brought him his gown, in requital of some beads and toys Smith had given him at his first arrival in Virginia.” One of the old warriors, whose son had been wounded at the time of the capture, was with difficulty restrained from killing him. The young Indian was at his last gasp, but Smith, wishing to send information to Jamestown, said that he had there a medicine of potent effect. The messengers sent on this errand made their way to Jamestown, “in as bitter weather as could be of frost and snow,” carrying a note from Smith, written upon “part of a table book.” They returned, bringing with them the articles requested in the letter, “to the wonder of all that heard it, that he could either divine, or the paper could speak.”

A plan was at that time on foot to make an attack upon the colony, and such rewards as were in their power to bestow “life, liberty, land, and women” were proffered to Smith by the Indians, if he would lend his assistance.

They now made a triumphal progress with their illustrious captive, among the tribes on the Rappahanock and Potomac Rivers, and elsewhere; exhibiting him to the Youthtanunds, the Mattapamients, the Payankatanks, the Nantaughtacunds, and Onawmanients. Returning to Pamaunkee, a solemn incantation was performed, with a view to ascertain his real feelings towards them.

Having seated him upon a mat before a fire, in one of the larger cabins, all retired, ” and presently came skip ping in a great grim fellow, all painted over with coal mingled with oil; and many snakes and weasels skins stuffed with moss, and all their tails tied together, so as they met on the crown of his head in a tassel; and round about the tassel was a coronet of feathers, the skins hanging round about his head, back, and shoulders, and in a manner covered his face; with a hellish, voice and a rattle in his hand.” He sprinkled a circle of meal about the fire, and commenced his conjuration. Six more “such like devils,” then entered, fantastically bedaubed with red “Mutchatos ” (Mustaches) marked upon their faces, and having danced about him for a time, sat down and sang a wild song to the accompaniment of their rattles.

The chief conjurer next laid down five kernels of corn, and proceeded to make an extravagant oration with such violence of gesture that his veins swelled and the perspiration started from his body. “At the conclusion they all gave a short groan, and then laid down three grains more.” The operation was continued “till they had twice encircled the fire,” and was then varied by using sticks instead of corn. All these performances had some mystic signification, which was in part explained to the captain.

Three days were spent in these wearisome barbarities, each day being passed in fasting, and the nights being as regularly ushered in with feasts. Smith was, after this, entertained with the best of cheer at the house of Opitchapam, brother to the king. He still observed that not one of the men would eat with him, but the remains of the feast were given him to be distributed among the women and children.

He was here shown a bag of gunpowder, carefully preserved as seed against the next planting season.