Articles and books on Native American peoples of the past tend to focus on arrowheads and pottery, presenting an incomplete image of their day to day lives. The ancestors of the Creek Indians began living in permanent villages as early as 400 BC. By 0 AD they were building large villages and even larger ceremonial centers. Beginning around 900 AD at Ocmulgee National Monument near Macon, GA, their ancestors began construction of the first large town in the Southeast. It eventually consisted of a central complex of temples, warehouses and homes of the leaders, surrounded by seven neighborhoods with their own plazas and temples. There were at least 18 farming villages scattered over a 12 mile long core of the Ocmulgee River. Living in close contact with their neighbors for over 2000 years, the Creek Indians developed many customs that enhanced the quality of urban living.

Articles and books on Native American peoples of the past tend to focus on arrowheads and pottery, presenting an incomplete image of their day to day lives. The ancestors of the Creek Indians began living in permanent villages as early as 400 BC. By 0 AD they were building large villages and even larger ceremonial centers. Beginning around 900 AD at Ocmulgee National Monument near Macon, GA, their ancestors began construction of the first large town in the Southeast. It eventually consisted of a central complex of temples, warehouses and homes of the leaders, surrounded by seven neighborhoods with their own plazas and temples. There were at least 18 farming villages scattered over a 12 mile long core of the Ocmulgee River. Living in close contact with their neighbors for over 2000 years, the Creek Indians developed many customs that enhanced the quality of urban living.

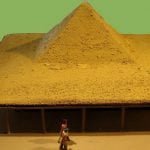

Archaeologists working at town sites in the Carolinas, eastern Tennessee, Georgia, eastern Alabama and Florida have frequently uncovered the footprints of structures that seem to be neither houses nor temples. The first such structure was discovered at Ocmulgee National Monument in the late 1930s and labeled “terrace houses.” They are typified by wrap around verandas and little evidence of domestic occupation other than a large cooking hearth. Usually, archaeologists find many animal bones in the soil around these “terrace houses.”

The mysterious sheds are at least the size of a house (15 ft. x 15’ ~ 5m x 5m,) but sometimes much larger. They are generally located near the central plaza of a village or of a neighborhood in a large town. They seem to be structures where meals were prepared for groups. Archaeologists couldn’t understand why there would be a need for public kitchens, so often just continued to call them “terrace houses.”

For decades, archaeologists were puzzled by these “terrace houses” until communications opened up between Creek scholars and archaeologists. Creeks immediately knew what the structures were. They were topah-sofkees. The word topah-sofkee means “hospitality board-grits.” However, grits was just one of the hot, nutritious dishes that might be bubbling in a pot 24 hours a day. Another common dish was what is now called Brunswick stew. Under the shed were usually found baskets of flat corn cakes, hush puppies fortified with vegetables, and fried corn bread that had been sweetened with bits of dried fruit.

For decades, archaeologists were puzzled by these “terrace houses” until communications opened up between Creek scholars and archaeologists. Creeks immediately knew what the structures were. They were topah-sofkees. The word topah-sofkee means “hospitality board-grits.” However, grits was just one of the hot, nutritious dishes that might be bubbling in a pot 24 hours a day. Another common dish was what is now called Brunswick stew. Under the shed were usually found baskets of flat corn cakes, hush puppies fortified with vegetables, and fried corn bread that had been sweetened with bits of dried fruit.

The topah-sofkee was really was much more than a kitchen for banquets. It was an always-open-for-business that served free, hot food to the needy, travelers and hunters arriving home late at night.

In addition, they were kitchens for clan festivities, a location where women would be fed while on their mandatory abstinence from domestic chores during their monthly period, or perhaps communal dining halls for the elite, who generally had their meals prepared by others. Any person invited into the village or town could eat till full at a topah-sofkee. One of the primary duties of the high leaders of a Creek province was to make sure that no person within their jurisdiction ever went hungry.