Montana, mountainous or full of mountains 1 is a name, as herein used, no less beautiful than significant. From the summit of its loftiest peak – Mount Hayden – may be seen within a day’s ride of each other the sources of the three great arteries of the territory owned by the United States – the Missouri, the Colorado, and the Columbia. From the springs on either side of the range on whose flanks Montana lies flow the floods that mingle with the North Pacific Ocean, the Gulf of California, and the Gulf of Mexico. The Missouri is 4,600 miles in length, the Columbia over 1,200, and the Colorado a little short of 1,000; yet out of the springs that give them rise the Montana may drink the same day. Nay, more: there is a spot where, as the rainfalls, drops descending together, only an inch asunder perhaps, on striking the ground part company, one wending its long, adventurous way to the Atlantic, while the other bravely strikes out for the Pacific. These rivers, with their great and numerous branches, are to the land what the arteries and veins are to the animal organism, and whoso action is controlled by the heart; hence this spot may be aptly termed the heart of the continent. From New Orleans to the falls of the Missouri there is no obstacle to navigation. Wonderful river!

Could we stand on Mount Hayden, we should see at first nothing but a chaos of mountains, whose confused features are softened by vast undulating masses of forest; then would come out of the chaos stretches of grassy plains, a glint of a lake here and there, dark canons made by the many streams converging to form the monarch river, rocky pinnacles shooting up out of interminable forests, and rising above all, a silvery ridge of eternal snow, which imparts to the range its earliest name of Shining Mountains. The view, awe-inspiring and bewildering, teaches us little; we must come down from our lofty eminence before we can particularize, or realize that mountains, lakes, forests, and river-courses are not all of Montana, or that, impressive as the panorama may be, greater wonders await us in detail.

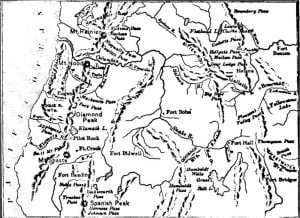

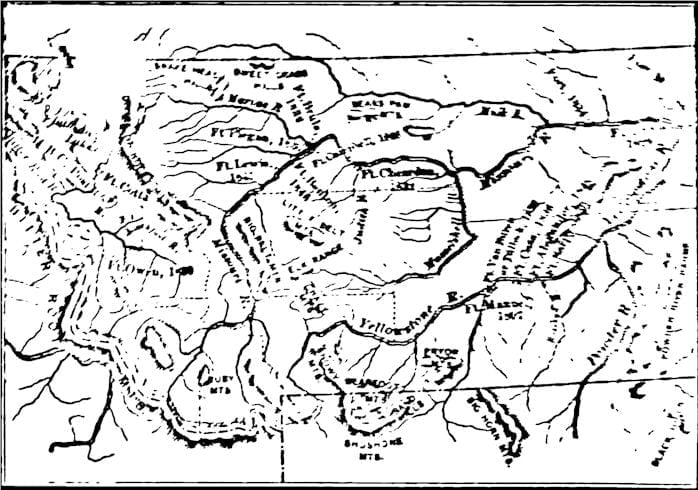

The real Montana with which I have to deal consists of a number of basins among these mountains, in which respect it is not unlike Idaho. Commencing at the westernmost of the series, lying between the Bitterroot and Rocky ranges, this one is drained by the Missoula and Flathead Rivers, and contains the beautiful Flathead Lake, which is at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, in latitude 48°. From the lake south for fifty miles is a gently undulating country, with wood, grass, and water in abundance, and a good soil. The small valley of the Jocko, which is reached by crossing a range of hills, is a garden of fertility and natural loveliness. But true to the character of this montane region, another and a higher range must be crossed before we can get a glimpse of the grander and not less lovely Hellgate 2 Valley, furnished also with good grass and abundance of fine timber. Branching off to the south is the valley of the Bitterroot, another fertile and picturesque region. The Hellgate and Bitterroot valleys are separated from Idaho on the west by the Bitterroot Range, on the lofty peaks of which the snow is from year to year. These mountains have a general trend southeast and northwest, and cover an area of seventy-five miles from west to east, forming that great mass of high, rough mineral country so often referred to in my description of Idaho, and which is covered with forest.

Passing out of the Bitterroot and Hellgate valleys to the east, we travel through the pass, which gives its name to the latter. This canon is forty miles in length, cutting through a range less lofty than those on the west. Through it flows the Hellgate River, receiving in its course several streams, the largest of which is the Big Blackfoot, which heads in the Rocky Mountains, near Lewis and Clarke’s pass of 1806. At the eastern end of this canon is Deer Lodge Valley, watered by the Deer Lodge River, rising in the Rocky Mountains south and east of this pass, and becoming the Hellgate River where it turns abruptly to the west after receiving the waters of the Little Blackfoot, and which still farther on becomes the Missoula. Other smaller streams and valleys of a similar character go to make up the northwestern basin, which is about 250 miles long by an average width of 75 miles. It is the best timbered portion of Montana, being drained toward the northwest, and open to the warm, moisture laden winds of the Pacific, which find an opening here extending to the Rocky Mountains.

The northeast portion of Montana, 3 bounded by the Rocky Mountains on the west, the divide between the Missouri and the river system of the British possessions on the north, and by a broken chain of mountains on the south, is drained toward the east by the Missouri River, and is a country essentially different from the grassy and well-wooded regions west of the great range. It constitutes a basin about 400 miles in length and 150 in breadth, the western portion being broken occasionally by mountain spurs, or short, isolated upheavals, such as the Little Rockies, the Bear Paw Mountains, or the Three Buttes, and taken up in the eastern portion partly by the Bad Lands. Its general elevation is much less than that of the basin just described, 4 yet its fertility is in general not equal to the higher region west of the Rocky Mountains. There is a belt of grassland from ten to twenty miles in width, extending along at the foot of the mountains for a hundred and fifty miles, backed by a belt of forest on the slopes of the higher foothills. The lower plains are for some distance along the Missouri a succession of clay terraces, entirely sterile, or covered with a scanty growth of grass of inferior nutritive quality. Through this clay the rivers have worn canons several hundred feet in depth, at the bottom of which they have made themselves narrow valleys of fertile soil washed down from the mountains, supporting some Cottonwood timber and grass. Higher, toward the south, about the heads of the tributaries of the Missouri, there is a region of good agricultural and grazing lands lying on both sides of the Little Belt and Snow Mountains. The scenery of the upper Missouri also presents, for a hundred or more miles, commencing below the mouth of the Jefferson fork, a panorama of grandeur and startling effects, the Gate of the Mountains, a canon five miles in length and a thousand feet deep, being one of the finest river passes in the world in point of beauty.

South of the vast region of the main Missouri are three separate basins; the first drained to the east by the Jefferson fork of that river, and by its branches, the Bighole 5 and Beaverhead, the latter heading in Horse Prairie, called Shoshone Cove by Lewis and Clarke, who at this place abandoned canoe travel, and purchased horses of the Indians for their journey over the mountains. They were fortunate in their choice of routes, this pass being the lowest in the Rocky range, and very gentle of ascent and descent. The Beaverhead-Bighole basin is about 150 miles by 100 in extent, containing eight valleys of considerable dimensions, all having more or less arable land, with grass and water.

East of this section is another basin, drained by the Madison and Gallatin forks of the Missouri, and. having an extent of 150 miles north and south, and 80 east and west. In it are five valleys, containing altogether a greater amount of agricultural land than the last named.

Last is the Yellowstone basin. It contains eight principal valleys, and is 400 miles long and 150 miles wide. The Yellowstone River is navigable for a distance of 340 miles; there is a large amount of agricultural and grazing lands along its course, and between it and the Missouri, with which it makes a junction on the eastern boundary of Montana. About the head of this river, named by early voyageurs from the sulphur tint of the rocks which constitute its banks in many places, cluster a world of the world’s wonders. The finger marks of the great planet making forces are oftener visible here than elsewhere. Hundreds of ages ago about these mountain peaks rolled an arctic sea, the wild winds sweeping over it, driving the glittering icebergs hither and thither. When the mountains were lifted out of the depths by volcanic forces they bore aloft immense glaciers, which lay for centuries in their folds and crevices, and slid and ground their way down the wrinkled slopes, tracing their history in indelible characters upon the rocks, while they gave rise and direction to the rivers, which in their turn have scooped out the valleys, and cut the immense canons which reveal to us the nature of the structure of the earth’s foundations.

Volcanic action is everywhere visible, and has been most vigorous. All the stratified rocks, the clays and slates in the Yellowstone range, have been subjected to fire. There are whole mountains of breccia. Great ravines are filled with ashes and scoria. Mountains of obsidian, of soda, and of sulphur, immense overflows of basalt, burnt out craters filled with water, making lakes of various sizes, everything everywhere points to the fiery origin, or the later volcanic history of the Yellowstone range.

The valley of the Yellowstone where it opens out presents a lovely landscape of bottom-lands dotted with groves, gradually elevated benches well grassed and prettily wooded, reaching to the foothills, and for a background the silver-crested summits of the Yellowstone range. As a whole, Montana presents a beautiful picture, its Bad Lands, volcanic features, and great altitudes only increasing the effect. In its forests, on its plains, and in its waters is an abundance of game, buffalo, moose, elk, bear, deer, antelope, mountain sheep, rabbits, squirrels, birds, water-fowl, fish, 6 not to mention the many wild creatures which civilized men disdain for food, such as the fox, panther, lynx, ground-hog, prairie-dog, badger, beaver, and marten. The natural history of Montana does not differ from that of the west side of the Rocky Mountains, except in the matter of abundance, the natural parks on the east side of the range containing almost a superfluity of animal life, a feature of the country which, taken in connection with the hardy and warlike indigenous tribes, promises well for the prosperity of the white race which unfolds therein.

As to the climate, despite the general elevation of the territory, it is not unpleasant. The winter camps of the fur companies were more often in the Yellowstone Valley than at the South Pass or Green River. Here, although the snow should fall to a considerable depth, their horses could subsist on the sweet cottonwood, of which they were fond. But the snow seldom fell to cover the grass for any length of time, or if it fell, the Chinook wind soon carried it off; and it is a remarkable trait of the country, that stock remains fat all winter, having no food or shelter other than that furnished by the plains and woods. 7 Occasional ‘cold waves’ affect the climate of Montana, along with the whole region east of the Rocky Mountains, sometimes accompanied with high winds and driving snow. 8 But the animals, both wild and tame, being well fed and intelligent, take care to escape the brief fury of the elements, and seldom perish. 9 This for the surface, beneath which, could the beholder look, what might he not see of mineral riches, of gold, silver, and precious stones, with all the baser metals I Montana is the native home of gold. Nowhere is it found in so great a diversity of positions; in the oldest igneous and metamorphic rocks, in the micacious slates, in alluvial drifts of boulders and gravel, sometimes in beds of ferruginous conglomerates, and infiltrated into quartz, granite, hornblende, lead, iron, clay, and every Kind of pseudomorphs. In Montana quartz is not always the ‘mother of gold,’ where iron and copper with their sulphurets and oxides are often a matrix for it. Even driftwood long embedded in the soil has its carbonaceous matter impregnated with it; and a solution of gold in the water is not rare. 10 The forms in which the precious metal exists in Montana are various. It is not always found in flattened, rounded, or oval grains, but often in crystalline and arborescent forms. 11 The cube, octahedron, and dodecahedron are not uncommon forms, the cube, however, being most rare. Cubes of iron pyrites are sometimes covered with crystals of gold. 12 Beautiful filaments of gold frequently occur in quartz lodes in Montana, and more rarely spongiform masses. 13 Curiously exemplifying the prodigality and eccentricity of the creative forces, cubes of galena, strung on wires of gold, and rare tellurium, are found in the same place in the earth.

Silver is present here, also, in a variety of forms, as the native metal, in sulphides, chlorides of various colors, antimonial silver, ruby, and polybasite, with some rarer combinations. Gems, if not of the finest, are frequent in gulch soils where gold is found. By analogy, there should be diamonds where quartz pebbles, slate clay, brown iron ore, and iron sand are found. Sapphires, generally of little value because of a poor color, beryl, aquamarine, garnet, chrysoberyl, white topaz, amethyst, opal, agate, and moss-agate are common. Of these the amethyst and the moss-agate are the most perfect in points of fineness and color. Of the latter there are several varieties, white, red, black, and green, in which the delicate fronds of moss, or other arborescent forms, are defined by the thin crystals of iron oxides, manganese, or other mineral matter in the process of formation; crystals of epidote, dark red and pale green, form veins in the earth; calcite, of a beautiful light red color, marbles, tin ores, cinnabar, magnesia, gypsum, and fire clays, base metals, coal – these are what this Montana storehouse contains, waiting for the requirements of man.

There have been those who talked of catacombs in Montana, of underground apartments tenanted by dead warriors of a race as far back as one chooses to go. However this may be, it is certain that in the mauvaise terres, or bad lands of the early French explorers, are immense catacombs of extinct species of animals. These Bad Lands form one of the wonders of the world, which must be counted since the discovery of this region to be at least eight. The region is geologically remarkable. Under a thin gray alkaline alluvium, which supports only occasional pines and cedars on the banks of the streams, is a drab-colored clay or stone, which covers, in most places, beds of bituminous coal, or lignite. The soil is interspersed with seams of gypsum in the crystalline form, which sparkle in the sun like necklaces of diamonds upon the hills and river-bluffs. Other seams consist of spar iron, carbonates of magnesia, and deposits of many varieties of the spar family in beautiful forms of crystallization. In the alluvium are boulders of lime and sandstone, containing as a nucleus an ammonite, some of which are five feet in diameter, and glowing when discovered with all the colors of the rainbow. Fossil crustaceans also abound in the shales, their shining exposed edges making a brilliant mosaic. Beds of shells of great depth, and of beautiful species, are exposed in the walls of canons hundreds of feet beneath the surface. Balls of sandstone, in size from a birdshot to half a ton’s weight, are found on the Missouri River, the centre of each being a nucleus of iron. Bones of the mammoth elephant, of a height a third greater than the largest living elephants, and of twice their weight, are scattered through the land, together with other fossils. In some localities the country is sculptured into the likeness of a city, with narrow and crooked streets, white, shining, solitary, and utterly devoid of life – the most striking picture of desolation that could be imagined. Fancy fails in conjecturing the early developments of this region, now dead past all resurrection. 14

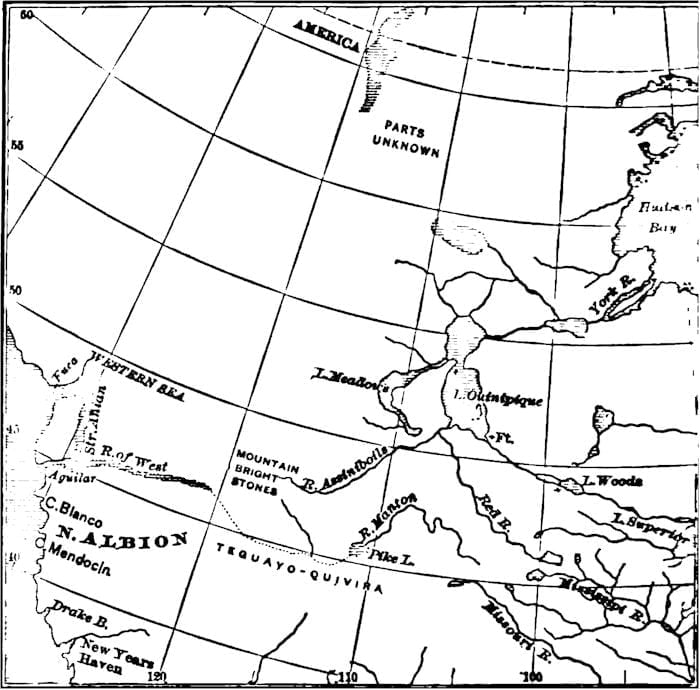

It is worthy of notice that the shining appearance of the Bad Lands, which the Indians of Montana described to the tribes farther east, and they to others in commercial relations with the French in Canada, and which became mingled with descriptions of the great mountain range, should lead to a journey of exploration in search of the Shining Mountains, where diamonds and gold abounded, by the Canadian French.

For the progress of these mercurial people since 1728 westward along the line of the Great Lakes, for the lies of Baron La Hontan, the adventures of Verendrye 15 the journey of Moncaht Apé, the explorations of Lewis and Clarke with the names of the first white men in Montana 16 and the doings of the fur hunters 17 and missionaries in these parts, the reader is referred to my History of the Northwest Coast, in this series. 18

The first actual settlers of Montana, not missionaries, were some servants of the Hudson’s Bay Company and all foreign-born except the half-breeds. These men seldom had any trouble with the Indians, with whom they traded and dwelt, and among when they took wives. 19 They were protected against the Blackfoot tribe by the Flatheads, whom they assisted, in their turn, to resist the common foe. But there was not the same security for other white residents. In 1853 John and Francis Owen, who bought the building of St Mary’s mission, and established themselves, as they believed, securely in the Bitterroot Valley, were unable to maintain themselves longer against the warlike and predatory nation from the east side of the Rocky Mountains, and set out with their herds to go to Oregon, leaving their other property at the mercy of the savages. They had not proceeded far when they were met by a detachment of soldiers under Lieutenant Arnold, of the Pacific division of the government exploring expedition in charge of I. I. Stevens, coming to establish a depot of supplies in the Bitterroot Valley for the use of the exploring parties which were to winter in the mountains. This fortunate circumstance enabled them to return and resume their settlement and occupations. 20

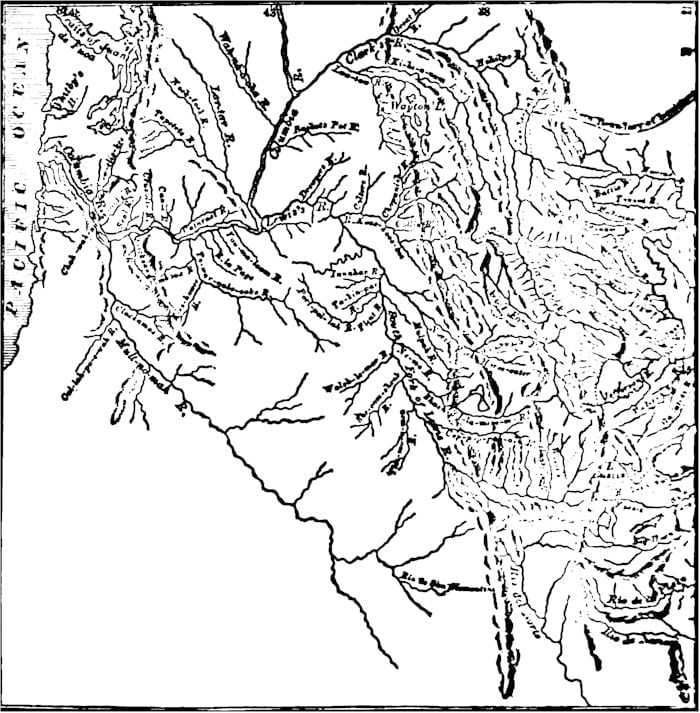

Since the explorations of Lewis and Clarke, no government expedition had followed the course of the Missouri in Montana, if we except some geological researches by Evans, until the railroad survey under Stevens was ordered; and to this expedition, more than to any other cause, may the gold discoveries in Idaho and Montana, and the ultimate rapid settlement of the country, be credited. 21 Stevens left at Fort Benton, and west of there along the line of exploration in Montana in the winter of 1853-4, one of his assistants, James Doty, to study under Alexander Culbertson the character and feelings of the Indian tribes of the mountains, preparatory to a council of treaty with the Blackfoot nation; Lieutenant Grover, to observe the different passes, with regard to snow, during the winter; and Lieutenant Mullan, to explore for routes in every direction. These officers and Mr Doty seemed to have failed in nothing. Mullan travelled nearly a thousand miles, crossing the divide of the Rocky Mountains six times from October to January, passing the remainder of the winter at Cantonment Stevens in the Bitterroot Valley. Grover on the 2d of January left Fort Benton, crossing the Rocky Mountains by Cadotte’s pass on the 12th, and finding the cold severe, the temperature by day being 21° below zero. On the 16th, being on very elevated ground, at sunrise the mercury stood at 38° below zero. In the Hellgate and Bitterroot valleys it was still from 10° to 20° below zero, which was cold weather even for the mountains. On the 30th he left Fort Owen for Walla Walla, having warmer weather, but finding more snow from Thompson prairie on Clarke fork to Lake Pend d’Oreille than in the Rocky Mountains, and arriving at Walla Walla on the 2d of March.

Meantime Stevens had gone to Washington City to advocate the building of the Northern Pacific railroad and the construction of a preliminary wagon-road from Fort Benton to Fort Walla Walla, On receiving the reports of Grover and Mullan the following spring, he directed Mullan and Doty to continue their explorations, and their efforts to promote peace among the natives, especially between the Blackfoot and Flathead tribes. Of the temporary failure of the scheme of a wagon-road, through the combination of the southern tribes for war in 1855, the narrative has been given. After the subjugation of the natives, Mullan was permitted to take charge of this highway, which played its part in the early history of the settlement of Montana, and its trade and travel. The road was first advocated as a military necessity to save time and money in moving troops across the continent, and shortening land travel for the annual immigrations. The rumored discovery of gold in some places 22 along the route, with the natural spreading out of the mining population, attracted first to the British Columbia and Colville mines, together with the requirements for the transportation of military stores during the Indian war, completed the chain of sequences which led up to actual immigration 23 and settlement.

One of the projects of Stevens and Mullan was to induce owners of steamboats in St Louis to send their boats, which had never run above Fort Union, 24 up the Missouri as far as Fort Benton. The Robert Campbell in which a part of Stevens’ expedition ascended the Missouri, advanced seventy miles above Fort Union in 1853, when her course was arrested by sand bars. 25

In 1858 and 1859 a steamer belonging to the firm of Chouteau & Company of St. Louis ascended to Fort Benton and Fort Brulé 26 to test the practicality of navigating the Missouri in connection with the military road, the construction of which was commenced in the latter year. In 1860 the further test was made of sending three hundred soldiers, under Major Blake, recruits to the army in eastern Washington and Oregon, to Fort Walla Walla by the River route and the Mullan road, which was so far completed that wagons passed over it in August of that year, conveying the troops from Fort Benton to their destination. 27 By the time the road was quite finished, which was not until September 1862, such changes had taken place with respect to the requirements of travel that a portion of it was relocated; but its existence was of great temporary benefit to the whole country. 28

The time had now approached when this montane region could no longer remain the common ground of Indian tribes and white traders, where a travelling party was a notable event, and a steamboat a surprise. The genii of the mountains could no longer hide their secrets, and their storehouses once invaded, all was turmoil.

Citations:

- Many infer that the word is of Spanish origin, a corruption, perhaps, of Montana a mountain, but it is purely Latin. It was a natural adoption, and the manner of it is given elsewhere.[

]

- The name of Hellgate Rood was given to a circular prairie at the mouth of a cañon, the passage of which was so dangerous, from Indian ambush, to the fur hunters and trappers, that in their nomenclature they could find no word so expressive as Hellgate. Virginia and Helena Post, Oct. 14, 1866; White’s Or, 289.[

]

- In Ingersoll’s Knocking around the Rockies 192-202, there are some bits of description touching Montana’s physical features worth reading, though taken together, no very clear notion of the country could be obtained from the book.[

]

- The following table shows the relative positions and climatic peculiarities of these two natural divisions of Montana:

Description Elevation Summit of Bitterroot range, near the pass 5,089 Junction of the Missoula and St Regis de Borgia Rivers 2,897 Bitterroot Valley, at Fort Owen 3,284 Big Blackfoot River, near mouth of Salmon Trout Fork 3,966 Deer Lodge, at Deer Lodge City 4,763 Prickly Pear Valley, near Helena 4,000 Mullan’s Pass of the Rocky Mountains 6,283 Lewis and Clarke’s Pass 6,519 Forks of Sun River 4,114 Fort Renton, Missouri River 2,780 Fort Union, mouth of Yellowstone 2,022 - This valley was formerly called by the French Canadian trappers, Le Grand Trou, which literally means big hole, from which the river took its name. The mountain men used this word frequently in reference to these elevated basins, as Jackson’s Hole, Pierre’s Hole, etc. McClure gives a different origin in his Three Thousand Miles, 309, but he is misinformed.[

]

- Buffalo used formerly to be numerous on the plains between the South Pass and the British possessions, the Nez Percé “going to buffalo” through the Flathead and Blackfoot country, and the fur companies wintering on the Yellowstone in preference to farther south, both on account of climate and game. The Montana buffalo is said to have been smaller, less humped, and with finer hair than the southern animal. In I865 a herd of them were seen on the headwaters of Hellgate River for the first time in many years. Idaho World, Aug. 28, 1865. The reader of Lewis and Clarke’s journal will remember their frequent encounters with the huge grizzly. See also the adventures of the fur hunters with these animals in Victoria River of the West. Besides the grizzly, black, brown, and cinnamon bears were abundant.[

]

- The yearly mean temperature of Deer Lodge City, the elevation being nearly 5,000 feet, is 40° 7′, and the mean of the seasons as follows: Spring 41° 6′, summer 69° 7′, autumn 43° T, winter 19° 9′. This temperature is much lower than that of the principal agricultural areas. The total yearly rainfall is 17 inches, and for the growing season, April to July, 9.15 inches, Norton’s Wonderland, 89. Observations made at Fort Benton from 1872 to 1877 gave a mean annual temperature of 40° and an average of 291 clear days each year. The average temperature for 1806 at Helena, which is 1,000 feet higher than many of the valleys of Montana, was 44° 5′. The snowfall varies from 4½ inches to 41½. The report of the U. S. signal officer at Virginia City gives the lowest temperature in 6 years, with one exception, at 19° below zero, and the highest at 94° above. Observations taken in the lower valleys of Montana for a number of years show the mean annual temperature to be 48°. Navigation opens on the Missouri a month earlier near Helena than at Omaha. The rainy season usually occurs in June. Omaha New West, Jan. 1879; Schott’s Distribution and Variations, 48-9; Montana Scraps, 54, 69-71.[

]

- These storms, which are indeed fearful on the elevated plateau and mountains, are expressively termed ‘blizzards’ in the nomenclature of the frontier. The winter of 1831-2 is mentioned as one of the most severe known, before or since.[

]

- Shoup, in his Idaho, MS., 4, speaking of stock raising, says: ‘Cattle of all kinds thrive in the hardest winters without stall-feeding, and we lost none through cold or snow. My loss in the hardest winter in 5,000 head was not more than one per cent.’[

]

- This statement I take from an article by W. J. Howard, in the Helena Rocky Mountain Gazette, Dec. 24, 1868. The author writes like a man acquainted with his subject. Might not this account for the presence of flour gold in certain alluvial deposits?[

]

- The same may be said of California, Oregon, and Idaho. I have seen a stem with leaves, like the leaf stalk of a rose, taken from a creek-bed in California, and the most elegant crystalline forms from the Santiam mines of Oregon.[

]

- The Venus lode, in Trout Creek district, Indian, Trinity, and Dry gulches in the vicinity of Helena, have produced some beautiful tree forms of crystallization. Also other crystalline forms of gold have been found near the head of Kingsbury gulch, on the east side of the Missouri River, in seams in clay slate overlying granite. Helena Rocky Mountain Gazette, Doc. 24, 1868.[

]

- The finest specimens of thread gold, says Howard, were found in the Uncle Sam lode, at the head of Tucker gulch. A sponge-shaped mass valued at $300 was taken from McClellan gulch, both in the vicinity of Mullan’s pass. See Virginia Montana Post, June 2, 1866; Deer Lodge Independent, Nov. 30, 1867; Deer Lodge New Northwest, Dec. 9, 1870.[

]

- It is not in the Bad Lands alone that we find interesting fossil remains in Montana. Teeth and bones of extinct fossil mammals have been exhumed at various points, as in Alder gulch, at Virginia City, where also an enormous tusk has been dug up, and shells, in state of almost perfect preservation. Forty feet from the surface in Lost Chance gulch a tooth, in good condition, corresponding to the 6th upper molar of the extinct elephasintormedius was found. A little lower two tusks, one measuring feet in length and 20 inches in circumference, were taken out, this being but a part of the whole. New York gulch produced a tooth 14 inches long and 5 inches across. Helena Rocky Mountain Gazette, Dec. 31, 1808. Many hints as to the geography and resources of Montana have been gathered from the Deer Lodge Independent; Helena Independent; Helena Herald; Helena Rocky Mountain Gazette; Deer Lodge New Northwest; Virginia City Post: and the local journals of Montana generally; also, from Steven’s Northwest; Daly’s Address Am. Geog. Soc., 1873; Smally’s Hist. N. Pac, R., and H. Ex. Doc, 326, 248-71, 42d cong. 2d sess.; Overland Monthly, ii. 379-80.[

]

- It was the 1st of Jan., 1743, when Verendrye reached the Shining Mountains. The point at which the ascent was made was near the present city of Helena, where the party discovered the Prickley Pear River, and learned of the Bitterroot. They described the Bear’s Tooth Mountain near Helena, and in other ways have left ample evidence of their visit.[

]

- The treaty of Ryswick, concluded in 1695, defined the boundaries of the English, French, and Spanish in America; but so crude were the notions of geography which prevailed at that period, that these boundaries were after all without intelligibility. The Spanish possessions were bounded on the north by the Carolinas of the English, but to the west their extent was indefinite, and conflicted with the French claim to all north of the mouth of the Mississippi and west of the Alleghanies, which was called Louisiana. France also claimed the region of the great lakes and river St Lawrence, under the title of Canada. The English colonies lay cast of the Alleghanies, from Maine to Georgia. During the latter part of the 17th century and early in the 18th the French explored, by the help of the Jesuit missionaries, the valley of the Mississippi, and established a chain of stations, one of which was St Louis, penetrating the great wilderness in the middle of the continent, well toward the great divide.[

]

- A fort was built at the mouth of the Bighorn in 1807, by one Manuel. In 1808 the Missouri Co., under the leadership of Maj. Henry, penetrated to the Rocky Mountains, and was driven out of the Gallatin and Yellowstone country by the Blackfoot tribe, with a loss of 33 men and 50 horses. But in the following year he returned, and pursued his adventures westward as far as Snake River, naming Henry Lake after himself. In 1816 Burrell, a French trader, travelled from the mouth of the Yellowstone across the plains to the month of the Platte River. The St Louis and American Fur Company soon followed in his footsteps. In 1823 W. H. Ashley led a company to the Rocky Mountains, and was attacked on the Missouri below the mouth of the Yellowstone, losing 26 men. The Missouri Co. lost seven men the same year, and $15,000 worth of goods on the Yellowstone River, by the Indians. There was much blood, of red and white men, shed during the operations of the fur companies. Of 200 men led by Wyeth into the mountains in 1832, only 40 were alive at the end of 3 years. Victoria River of the West. The names of Henry, Ashley, Sublette, Jackson, Bridger, Fitzpatrick, Campbell, Bent, St Vrain, Gantt, Pattie, Pilcher, Blackwell, Wyeth, and Bonneville are a part of the history of Montana. Many of their employees, like Carson, Walker, Meek, Newell, Godin, Harris, and others, were men not to bo passed over in silence, to whom a different sphere of action might have brought a greater reputation. If not settlers, they made the trails which other men have found it to their interest to follow.

In 1829 there was established at the mouth of the Yellowstone, by Kenneth McKenzie of the American Fur Company, a fortified post called Fort Union, the first on the Missouri within the present limits of Montana. McKenzie was a native of Scotland, and served in the Hudson’s Bay Co., from which he retired in 1820, and two years afterward located himself on the upper Missouri as a trader, where he remained until 1829. From that date to 1839 he was in charge of the American company’s trade, but Alexander Culbertson being appointed to the position, he went to reside in St Louis. James Stuart, in Con. Hist. Soc. Montana, 88.

In 1830 the American Fur Co. made a treaty with the Piegans, a branch of the Blackfoot nation; and in 1831 Captain James Kipp erected another post named Fort Piegan, at the mouth of Maria River, in the country of the Piegans, which extended from Milk River to the Missouri, and from Fort Piegan to the Rocky Mountains. The situation, however, proved untenable, on account of the bad disposition of the Indians, and for other reasons, all of which led to its abandonment in the autumn of 1832, when Kipp removed to a point opposite the mouth of Judith River. But here again the situation was found to be unprofitable, and later in the season D. D. Mitchell of the same company erected Fort Brule at a place on the south side of the Missouri called Brulé Bottom, above the month of Maria River. The following year Alexander Culbertson took charge of this fort, remaining in command until 1841, when he went to Fort Laramie, and F. A. Cheardon assumed the charge.

Cheardon proved unworthy of the trust, becoming involved in a war with the Piegans, and losing their trade, in the following manner: A party of Piegans demanded admittance to the fort, which was refused, on which they killed a pig in malice, and rode away. Being pursued by a small party from the fort, among them was a Negro, they shot and killed him, after which the pursuing party returned to the fort. Cheardon then invited a large number of the Indians to visit the post, throwing open the gates as if intending the utmost hospitality. When the Indians were crowding in, he fired upon them with a howitzer, loaded to the muzzle with trade balls, killing about twenty men, women, and children. After this exploit he loaded the mackinaw boats with the goods of the establishment, burned the buildings of the fort, and descended to the post at the mouth of the Judith River, which he named Fort Cheardon.

Robert Campbell and William Sublette, of the Missouri Co., erected a fort five miles below Fort Union, in 1833; and in 1834 another sixty miles above, but sold out the same year to the American co., who destroyed these posts. In 1832 McKenzie of the latter company sent Tullock to build a post on the south side of the Yellowstone River, three miles below the Bighorn, to trade with the Mountain Crows. These Indians were insolent and exacting, lying and treacherous, but their trade was valuable to the fur companies. Tullock erected a large fort, which he named Van Buren. The Crows often wished the trading post removed to some other point, and to suit their whims. Fort Cass was built by Tullock, in 1836, on the Yellowstone below Van Buren; Fort Alexander by Lawender, still farther down, in 1848; and Fort Sarpy by Culbertson, at the mouth of the Rosebud, in 1850. This was the last trading post built on the Yellowstone, and was abandoned in 1853.

In l843 Culbertson returned from Fort Laramie to the Missouri, and built Fort Lewis, twenty-five miles above the mouth of Maria River, effecting a reconciliation with the Piegans, with whom he carried on a very profitable trade. Three years afterward this post was abandoned, and the timbers of which it was constructed rafted down the river eight miles, where Culbertson founded Fort Benton, in 1846. In the following year an adobe building was erected. In 1848 Fort Campbell was built a short distance above Fort Benton by the rival trailers Galpin, Labarge, & Co., of St Louis, who did not long occupy it, and successively a number of fortified stations on the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers have been built and occupied by traders who alternately courted and fought the warlike Montana tribes. They enriched themselves, but left no historical memoranda, and no enduring evidences of their occupation.[

]

- P. J. De Smet, missionary of the Society of Jesus, in the spring of 1840 left St Louis on a tour of exploration, to ascertain the practicability of establishing a mission among the Indians of the Rocky Mountains. Travelling with the American Fur Co. to their rendezvous on Green River, he there met a party of Flatheads, who conducted him to the Bitter Root Valley, where he remained teaching and baptizing from the 17th of July to the 29th of Aug., when he set out on his return, escorted as before by a company of Flathead warriors. His route was by the way of the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers to a fort of the American Fur Co., in the country of the Crows. From this point De Smet proceeded down the Yellowstone to Fort Union, with only a single companion, John de Velder, a native of Belgium, having several narrow escapes from meeting with parties of hostile Indians. From Fort Union they had the company of three men going to the Mandan village, whence De Smet proceeded, via forts Pierre and Vermilion, to Independence and St Louis.

In the following spring he set out again for the mountains, accompanied by two other priests, Nicolas Point, a Vendeean, and Gregory Mengarini, an Italian, and three lay brethren. Falling in at Westport with a party from New Orleans going to the mountains for a summer’s sport, and another party bound for Oregon and California, they travelled together to Fort Hall, where the Flatheads again met the missionaries to escort them to their country. In all this journeying De Smet evinced the utmost courage, believing that because he was upon an errand of mercy to benighted man the Lord of mercy would interpose between him and harm. I am impressed with his piety, but I do not fail to observe the egoism of his Christianity when he writes about other religious teachers, inspired, no doubt, by an equal philanthropy.

As far as Fort Hall the fathers had travelled with wagons, which there they seem to have transformed into carts, and to have travelled with these, by the help of the Indians, to Bitterroot Valley, going north from Fort Hall to the mouth of the Henry branch of Snake River, at the crossing of which they lost three mules and some bags of provisions, and came near losing one of the lay brethren, who was driving, but when the Indians rescued, and assisted to get his cart over. As De Smet nowhere mentions the abandonment of the carts, and as he had before proved himself a good road maker, I take it for granted that they arrived at the Bitterroot with their contents, among which was an organ. The route pursued was through the pass of the Utah and Northern Railroad, which was named The Fathers’ Defile, thence north, on the east side of the Rocky Mountains, and through a pass at the head of Deer Lodge River, and by the Hellgate cañon, to the Bitterroot Valley, where, on one of the last days of September 1841, the cross was set up among the Flatheads, and a mission founded, which was called St Mary’s Mission, and dedicated to the blessed virgin. A long account is given by the father, in his writings, of a journey to Fort Colville, and subsequent doings, which are unimportant.

In 1843 the Jesuit College sent out two priests- Peter De Vos and Adrian Hoeken – to assist Point and Mengarini, while De Smet was dispatched on a mission to Europe to secure both men and women for the mission. He was eminently successful, returning with both, and giving much assistance to the missions of western Oregon. De Vos and Hoeken arrived at St Mary in Sept. with three lay brothers. In 1844 Hoeken founded the mission of St Ignatius a short distance north of the Clarke branch of the Columbia, east and south of Fort Colville, in what was later Washington. Here De Smut found him on his return from Europe, and here again he visited him in 1845, having been down to the Willamette Valley and loaded a train of eleven horses with ploughs, spades, pickaxes, scythes, and carpenters ‘implements,’ brought by ship to the Columbia River. Not until these arrived could Hoeken commence any improvements, nor was much progress made until 1846. During these two years the father lived as Point had done, roaming about with the Indians and subsisting on camas-root and dried berries. After the first year Father Anthony Ravelli was associated with Hoeken. The first wheat raised was boiled in the husks for fear of waste. But in 1853-4 the mission of St Ignatius had a farm of 160 acres under improvement, a good mission-house of squared logs, with storeroom and shops attached, a large chapel tastefully decorated, barns and out-buildings, a windmill, and a grindstone hewn out of native rock with a chisel made by the mission blacksmith. Brick, tin ware, tobacco-pipes turned out of wood with a lathe and lined with tin, soap, candles, vinegar, butter, cheese, and other domestic articles were manufactured by the missionaries and their assistants, who were often the Indians. On the farm grew wheat, barley, onions, cabbages, parsnips, pease, beets, potatoes, and carrots. In the fields were cattle, hogs, and poultry. See Stevens’ N. P. R. B, Rept, in De Smet’s Missions, 282-4; Shea’s Missions, 146; Shea’s Indian Sketches, passim.

At the same time the Coeur d’Alene mission was equally prosperous. It was situated on the Coeur d’Alene River, ten miles above Coeur d’ Alene Lake. Here about 200 acres were enclosed and under cultivation; mission buildings, a church, a flourmill run by horse-power, 20 cows, 8 yokes of oxen, 100 pigs, horses, and mules, constituted a prosperous settlement. About both of these establishments the Indians were gathered in villages, enjoying with the missionaries the abundance, which was the reward of their labors. The mission of St Mary in 1846 consisted of 12 houses, neatly built of logs, a church, a small mill, and other buildings for farm use; 7,000 bushels of wheat, between 4,000 and 5,000 bushels of potatoes, and vegetables of various kinds were produced on the farm, which was irrigated by two small streams running through it. The stock of the establishment consisted of 40 head of cattle, some horses, and other animals. Then comes the old story. The condition of the Indians was said to be greatly ameliorated. They no longer suffered from famine, their children were taught, the women were shielded from the barbarous treatment of their husbands, who now assumed some of the labor formerly forced upon their wives and daughters, and the latter were no longer sold by their parents. But alas for human schemes of happiness or philanthropy! When the Flatheads took up the cross and the ploughshare they fell victims to the diseases of the white race. When they no longer made war on their enemies, the Blackfoot nation, these implacable foes gave them no peace. They stole the horses of the Flatheads until they had none left with which to hunt buffalo, and in pure malice shot their beef cattle to prevent their feeding themselves at home, not refraining from shooting the owners whenever an opportunity offered. By this system of persecution they finally broke up the establishment of St Mary in 1850, the priests finding it impossible to keep the Indians settled in their village under these circumstances. They resumed their migratory habits, and the fathers having no protection in their isolation, the mission buildings were sold to John Owen, who, with his brother Francis, converted them into a trading post and fort, and put the establishment in a state of defense against the Blackfoot marauders.

In 1853-4 the only missions in operation were these of the Sacred Heart at Coeur d’Alene, of St Ignatius at Kalispel Lake, and of St Paul at Colville-through certain visiting stations were kept up, where baptisms were performed periodically. In 1854, after the Stevens exploring expedition had made the country somewhat more habitable by treaty talks with the Blackfoot and other tribes, Hoeken, who seems nearly as indefatigable as De Smet, selected a site for a new mission, ‘not far from Flathead Lake, and about fifty miles from the old mission of St Mary.’ Here he erected during the summer several frame buildings, a chapel, shops, and dwellings, and gathered about him a camp of Kootenais, Flatbows, Pend d’Oreilles, Flatheads, and Kalispels. Rails for fencing were cut to the number of 18,000, a large field put under cultivation, and the mission of St Ignatius in the Flathead country became the successor of St Mary. In the new ‘reduction,’ the fathers were assisted by the officers of the exploring expedition, and especially by Lieutenant Mullan, who wintered in the Bitterroot Valley in 1854-5. In return, the fathers assisted Gov. Stevens at the treaty-grounds, and endeavored to control the Coeur D’Alenes and Spokanes in the troubles that immediately followed the treaties of 1855, of which I have given an account elsewhere. Subsequently the mission in the Bitterroot Valley was revived, and the Flatheads were taught there until their removal to the reservation at Flathead Lake, which, reserve included St Ignatius mission, where a school was first opened in 1863 by Father Urbanus Grassi. In 1858 the missionaries at the Flathead missions had 300 more barrels of flour than they could consume, which they sold to the forts of the American Fur Co. on the Missouri and the Indians cultivated fifty farms, averaging five acres each. In their neighborhood were also two sawmills. In 1871 the mission church of St Ignatius was pronounced the ‘finest in Montana,’ well furnished, and capable of holding 500 persons, while the mission farm produced good crops and was kept in good order. In addition to the former school, the Sisters of Notre Dame had two houses at this mission. At St Peter’s mission on the Missouri, in 1808, farming had been carried on with much success.

It cannot be said, although no high degree of civilization among the savages followed their efforts, that De Smet and his associates were not fearless explorers and worthy pioneers, who at least prepared the way for civilization, and the first to test the capability of the soil and climate of Montana fur sustaining a civilized population. The last mention I have made of the superior of the Flathead mission left him at St Ignatius in the summer of 1843. He travelled thereafter for several years more among the northern tribes, and visited Idaho and Montana, finally returning to his college at St Louis, where he ended his industrious life in May 1873, after the ground he had trod first as a settler was occupied by men of a different faith with far different motives.[

]

- Louis Brown, still living in Missoula co. in 1872, was one of these. He identified himself with the Flatheads, and made his home among them. Deer Lodge New Northwest, March 9, 187e. See also H. Misc. Voc, 59, 33d cong. 1st sess.[

]

- Ballou’s Adventures, MS., 13; Pac. R. R. Rept, i. 257.[

]

- Stevens’ party charged with the scientific object of the expedition consisted of Captain J. W. T. Gardiner, 1sr drag.; Leut. A. J. Donelson, Corps of Engineers, with ten sappers and miners; Leut. Beckman du Barry, 3d art; Leut Cuvier Grover, 4th art,; Leut John Mullan, 2d art; Isaac F Osgood disbursing agent; J, M. Stanley, artist; George Suckley, surgeon and naturalist; F.W. Lander and A. W. Tinkham, assist eng.; John Lambert topographer; George W. Stevens, William M. Graham, and A. Remenyi, in charge of astronomical and magnetic observations; Joseph F. Moffett, meteorologist; John Evans, geologist; Thomas Adams, Max Strobel, Elwood Evans, F. H. Burr and A. Jeklfaluzy, aids; and T. S. Everett quartermaster and commissary’s clerk. Pac. R.R. Rept. xii. 33.[

]

- Gold Creek was named by Mullan, because Lander, it is said, found gold there. Mullan’s Mil. Road Rept, 133.[

]

- There was an expedition by Sir George Gore, of Sligo in Ireland, to Montana, in 1854-6, simply for adventure. Gore had a retinue of 40 men, with 112 horses, 14 dogs, 6 wagons, and 21 carts. The party left St Louis in 1854, wintering at Laramie. Securing the services of James Bridger as guide, the following year was spent on the Powder River, the winter being passed in a fort, which was built by Sir George, eight miles above the mouth of the river. At this place he lost one of his men by illness – the only one of the party who died during the three years of wandering life. In the spring of 1856 Gore sent his wagons overland to Fort Union, and himself, with a portion of his command, descended the Yellowstone to Fort Union in two flatboats. At the fort he contracted for the construction of two mackinaw boats, the fur company to take payment in wagons, horses, etc., at a stipulated price. But a quarrel arose on the completion of the boats. Sir George insisting that the company were disposed to take advantage of his remoteness from civilization to overcharge him, and in his wrath he refused to accept the mackinaws, burning his wagons and goods in front of the fort, and selling or giving away his horses and cattle to Indians and vagabond white men rather than have any dealings with the fur company. Having satisfied his choler, his party broke up, and he, with a portion of his followers, proceeded on his flatboats to Fort Berthold, where he remained until the spring of 1857, when he returned to St Louis by steamer. Among these of the party remaining in the country was Henry Bostwick, from whom this sketch was obtained by F. George Heldt, who contributed it to the archives of the Hist. Soc. Montana, 144-8[

]

- The first steamboat to arrive at Fort Union was the Yellowstone, which reached there in 1832. After that, each spring a steamer brought a cargo of the American Fur Co.’s goods to the fort; but the peltries were still shipped to St Louis by the mackinaw boats of the company. Stuart, Con. Hist, Soc, Montana, 84.[

]

- The Robert Campbell had a double engine, was 300 tons burden, drew about 5 feet of water. She had been a first class packet on the Missouri and was too deep for navigation above Fort Union. Pac. R.R. Rept, xiii. 80, 82. Lieutenant Saxton, in his report, describes the keel boat (mackinaw) in which he descended the Missouri from Fort Benton to Leavenworth as 80 feet long, 12 feet wide, with 12 oars, and drawing 18 inches of water. In this he travelled over 2,000 miles between the 22d of September and the 9th of November,1853, his duty being to return to St. Louis the 17 dragoons and employees of the quartermaster’s department, who had escorted the Stevens expedition to Fort Benton.[

]

- It is usually stated that the first steamer to reach Fort Benton was the Chippewa in 1859. Or. Argus, Sept. 17, 1859; Con. Hist. Soc. Montana, 317; but Mullan in his Military Road Rept, 21 says that the steamboats arrived at Fort Benton in 1858 and 1859.[

]

- The Chippewa and the Key West brought the soldiers to Fort Benton.[

]

- After Gov. Stevens and Leut Mullan, the persons most intimately connected with the building of a wagon-road through the mountain ranges of Montana, then eastern Washington, were W. W. De Lacy and Conway R. Howard, civil engineers; Sohen and Engle, topographers; Weisner and Koleeki, astronomers; W. W. Johnson, James A. Mullan, and Leut J. L. White, H. B. Lyon, and James Howard, of the 3d U. S. art.[

]