Since they were rather uniform in pattern, it will doubtless yield a clearer picture if the common points of the pioneer schools are given rather than giving short references to each one.

Nearly all of the first school houses were built of unhewed or round logs and had roofs made of clapboards that had been split from some convenient oak of large size. These boards were generally two feet or more long, about eight inches wide, and were often laid without the use of nails, poles being used on each course to hold them down. These weight poles were fastened by pegs or tied bark and withes. Altogether it was a serviceable and durable roof, even though one could “see daylight” through it.

Heat came from a large fireplace. Where stone was convenient, the fireplace might be built of it. More often it was built of logs with a clay or stone lining. The chimneys, generally “stick and clay”, were double walled pens thoroughly plastered, inside and out, with clay. Weathering often caused this clay to crumble away, exposing the sticks. It was not an unusual thing to see where this had occurred, and fire had burned holes in the chimney. Both fireplace and chimney were outside the building proper. These fireplaces were not in anywise puny affairs – – – they often accommodated cuts of wood four feet or more long. In many cases, the teacher agreed, as part of his work, to cut the necessary fire-wood. The hearth was of stone or filled-in earth.

When not of earth, the floors were generally of puncheon construction. In making a puncheon floor, slabs were split from a log, the edges straightened and the upper surface smoothed by use of broad axe or adze. This method of construction did not produce a very tight or smooth floor, though it was a substantial one.

The ceiling, when present, was generally made of boards split from some forest tree. They were laid upon ceiling joists, made of poles that might occasionally be somewhat smoothed by use of a broad axe. These ceilings were often not more than 7 feet high. Smoke from the fireplace soon gave it a brownish tint that gradually deepened as one moved nearer the fire. In numerous cases the ceilings would be omitted, and one gazed directly at the roof.

The inside walls were often left with only the “chink and daubing” finish. Coat racks were made by boring small holes in the logs and driving pegs into them. On these the shawls,’ coonskin caps, and homespun clothing were hung. Larger shelves were placed at convenient places about the room. On one of these shelves the wooden water bucket and drinking gourd would be found. Other shelves of proper size and heights were arranged for writing desks at which the pupils stood with quill pen and oak gall-copper as ink to do their writing on foolscap paper. The room would not be complete without two pegs above and behind the teacher’s desk. On these two pegs the switches and pointers reposed, for corporal punishment was the rule of the day.

The idea that the window area of a schoolroom should be one-fifth or more of the floor area had not been born. One or two were considered as sufficient. There are recorded in-stances of a log being omitted on one side of the building in lieu of a window. In winter the light of the fireplace helped some. Altogether the school room was dimly lit.

Thus far the forest immediately about the building has furnished the materials used. In the matter of seats this still held true, for the benches were generally from logs split in half. The flat side of the log was smoothed by axe of adze. With a large auger, holes were bored in the rounded side of the half logs, and large pegs were fitted to serve as legs for the bench. In the early school, desks for the pupils were seldom seen.

Writing paper was comparatively rare. Slates were used for “doing sums” and for some writing. Even at that they were not so common and ‘may I borrow a slate’ was frequently heard. From time to time it was necessary to clean the writing from these slates. In order to facilitate the process, a pupil would spit rather liberally upon the slate. Occasionally this saliva was removed with a rag. Generally the palm of the hand was used for rubbing, and any surplus moisture was mopped off with the sleeve. This is certainly not a very attractive description, but it really happened that way.

Lunch was generally brought to school in baskets. Boys and girls sat on different sides of the house. Some of the more careful teachers insisted upon pupils cleaning their boots and shoes before coming into the building. High top leather boots were standard for boys. Girls wore high top shoes. In summer most of the boys and girls went barefoot. Head lice and scabies were frequently to be found.

Bullpen, wolf on the ridge, stink base, hat-ball, old sow, cat, sling dutch, lap jacket, one and over, and move up, games almost unknown now, were the prevailing ones for boys. Girls were sometimes admitted to a gentle game of cat or wolf on the ridge, but more often they had to be content with games like ante over or as it was sometimes called ‘andy’ over, London Bridge, Lemonade, go in and out the window, drop the handkerchief, skipping rope or some adaptation of a singing game.

To lend a little variety to school life an occasional spelling bee was held, a debating club or literary society met, or a singing school was held at night. The pupil who could ‘spell the school down’ was much admired. The singing school offered a bit of culture and a chance for the young people to do a reasonable amount of courting.

Textbooks were rather scarce, but a spelling book was considered indispensable. There were some reading texts, but the opportunity for selection was generally limited. Bibles, such copies of the classics as were to be had, books of history, along with almost all printed matter that came to hand, were used. Arithmetic texts were not at all plentiful, and one still finds manuscript forms of such books used in the first schools. Many subjects, considered indispensable now, were then unknown. Art consisted of a few pictures slyly produced by pupils who were careful to avoid the teacher’s attention while doing this work. An occasional teacher with some ability to sing had singing lessons. Physiology and hygiene were practically unknown. When such texts as were then used are found, they call forth broad smiles by their statements. Grammar texts were very formal and were used only by the more advanced pupils. ‘Language’ was practically unknown. Geography was reduced to a little more than an outline. Civics was hardly known, while manual arts and handicrafts lay far ahead.

The grades as we think of them today had not come. One progressed in school determined almost solely by the individual. Technique for teaching had not been formulated. Then, as now, an occasional capable teacher with a vision became the inspiration of the youngsters. On the average the schoolmasters were a strict and domineering sect, adhering closely to limited knowledge that was theirs. Generally they were active practitioners of the ‘no licking, no larpin’ creed. Often the teacher was an itinerant, staying only a term or so while he boarded around and then moving on about as mysteriously as he had come. To know that the pupil was studying it was sometimes required that they study aloud. The teacher, like a trained choir leader, could select and listen to any voice among the babble.

Despite the limited equipment, the teacher’s cultural attainments were above those of most of the other young men of the community, hence, some young lady, often a pupil, selected him as a likely prospect for a husband. Being human, he was generally a willing victim, and ‘itinerant’ days were ended.

Most teachers were men. An occasional girl or woman, endowed with unusual tact or daring, became a successful teacher, but they were exceptions. The overgrown and often rude boys generally required the brawn of a man to ‘teach’ them.

Since an organized free school system was not in general operation, these early ones were often ‘subscription’ schools, the teacher being paid by the parents of the pupils attending.

It is interesting to note that formal Education in the true sense of the word, for the area of Illinois actually began in the area of Prairie du Roc her, by the later village of St. Anne when in June 16, 1659, the first Catholic Bishop of Quebec arrived in the person of Francois de Montmorency de Lavel, with the title of Bishop of Petraea. Quebec numbered hardly 500 inhabitants, and the whole of Canada perhaps 2200 souls. Lavel organized a complete system of education: primary, technical, and classical. His seminary and preparatory seminary trained young men for the priest hood. In 1678 he founded an industrial school near later St. Anne to provide the colony with skilled farmers and artisans. His seminary developed in the course of centuries into the now famous Laval University. He was a man of undoubted patriotism, and threw the full weight of his powerful personality into the balance whenever there was question of proper administration, progress of the colony and its defense against the marauding savage.

At an early date in history, Illinois was assured of strong support for the education of its youth. In 1785, only two years after the thirteen states had signed a treaty of peace with Great Britain, Congress passed a law for the great unorganized territory west of New York and north of the Ohio River, of which Illinois was a part. This established support for the public schools.

The law divided the land into townships of thirty-six sections each, each section to comprise 640 acres. Everything earned on one section out of the thirty-six was to pay for the public schools. Two years later this became part of the Northwest Ordinance, which also declared for freedom of religion and excluded slavery from this territory.

When the new settlers arrived, they built one-room schoolhouses. Some were on the open prairie, and children had to walk miles to attend school. Besides, they had to help feed pigs and get the cows into pasture before they left for school in the mornings, and after school had to bring the cows back to the barn. Yet the farm children went to school as long as they could, for they wished to get an education.

According to publication #8 of the Illinois Historical Library, education in Prairie du Rocher was first recorded as early as August 1816 when Benjamin Sturgess gives notice “That he has opened a school at Prairie du Rocher, where he will teach the usual branches of English Education, viz: Writing, Reading and Common Arithmetic, also English Grammar, Geography, Surveying, Astronomy, Latin and Greek languages. He thinks Prairie du Rocher is as healthy as any place in the American Bottom,” which may have been understood at the time as not a very improbable statement. He declares that “good board can be obtained at moderate terms and so forth.”

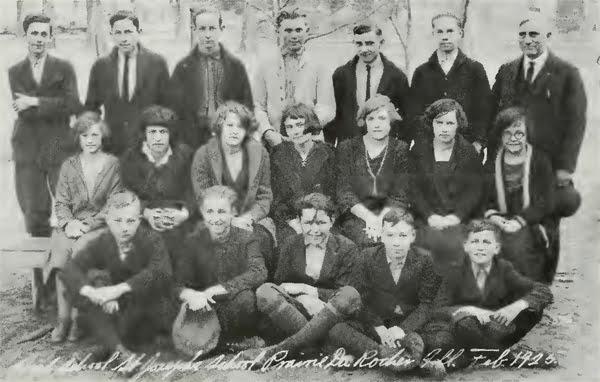

It cannot be exactly determined who many of the early teachers were, or where they held these classes. By 1820 Charles McNabb of one of the first Americans to settle in Prairie du Rocher, was teaching school in English. (During the pastorate of Father Charles Krewet two-thirds of the population of four hundred were French, German and English). In the 1850’s a small frame school of one room was built almost directly opposite the present church. An additional room was added to it in 1931. The parochial school was opened in the early sixties of the last century in this building. Under the supervision of Father Krewet and at a cost of $5000 the large brick building which took the place of the smaller frame school was erected in 1885 directly across the street from the rectory. It accommodated 175 children. In 1885 two lay teachers and three Sisters of the Most Precious Blood constituted the faculty. In 1893 a tornado damaged the school building to the extent of $1,300.

Peter Gregory Ehresmann was born January 22, 1872, to Peter Ehresmann and Catherine Ruegemer of Richmond Minnesota. He attended the College of St. Francis in Wisconsin and graduated from St. John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota. He taught school in Vincennes, Indiana, about two years before coming to Prairie du Rocher. He arrived here by boat in September, 1900 and taught here until his retirement as teacher in 1935. He continued as organist in St. Joseph’s Catholic Church until 1942. He served the community as City Clerk from 1937 to 1957. He died July 17, 1959.

Mr. Ehresmann was succeeded by Mr. Albin Schrage from Clinton County.

Following Mr. Schrage‘s resignation, Mr. Harry Dearworth, a former teacher of the local school, was persuaded to return to ‘Rocher and “head” the school in 1946.

In 1959 Sister Eustacia Goeckner was appointed principal; followed by Albert F. Hennrich in 1961.

In 1951, a school building was erected by the church at a reported cost of $275,000. In 1959 two temporary class rooms were added.

The cornerstone was laid at the present school in early 1971. The new building has a present capacity of 125. Cost was reported at 8140,000. A canopy connects this school with the church-owned building.