After the close of the Modoc War, General Davis ordered a march by the cavalry of 700 miles through the country threatened by dissatisfied tribes, in order to impress upon their minds the military force of the United States. But the reservation set apart for Joseph and his non-treaty followers remained unoccupied, and he continued to roam as before. The settlers on the Wallowa were impatient to know whether their indemnity money was to be paid, or what course the government would pursue, and wrote to their representative in congress, who replied that the commissioner of Indian affairs had assured him that the reservation order would be rescinded, and the settlers left undisturbed. 1 With this understanding, not only the settlers who were in the valley remained, but others joined them, and when the Indians overrun their land claims with imperious freedom, warned them off. It was not until June 10, 1875, that the president revoked his order, thereby formally releasing 1,425 square miles from any shadow of Indian title.

But Joseph regarded neither president nor people, and in 1876 another special commission was appointed by the Indian department at Washington to proceed to Idaho and inquire into the status of Joseph with regard to his tribe and the treaties. The commissioners were D. H. Jerome, O. O. Howard, William Stickney, A. C. Barstow, and H. Clay Wood. They arrived at Lapwai in November, where Joseph met them after a week of the customary delay, and proceeded to measure his intellectual strength with theirs.

When plied with questions, he had no grievances to state, and haughtily declared that he had not come to talk about land. When it was explained to him that his position in holding on to territory which had been ceded by the majority of the nation was not tenable according to the laws of other great nations; that the state of Oregon had extended its laws over this land; that the climate of the Wallowa Valley rendered it unfit for a reservation, as nothing could be raised there for the support of the Indians, with other objections for setting it apart for such a purpose, and a part of the Nez Percé reservation was offered instead, with aid in making farms, building houses, and instruction in various industries – he steadily replied that the maker of the earth had not partitioned it off, and men should not. The earth was his mother, and, sacred to his affections, too precious to be sold. He did not wish to learn farming, but to live upon such fruits as the earth produced for him without effort. Moreover, and this I think was the real motive, the earth carried chieftainship with it, and to part with it would be to degrade himself from his authority. As for a reservation, he did not wish for that, in the Wallowa or elsewhere, because that would subject him to the will of another, and to laws made by others. Such was substantially his answer, given hi a serious and earnest manner, for Joseph was a believer in the Smohollah doctrine, whose converts were called ‘dreamers’ an order of white man hating prophets which had arisen among the Indians. 2

The commissioners recommended that the teachers of the dreamer religion should not be permitted to visit other tribes, but should be confined to their respective agencies, as their influence on the non-treaty Indians was pernicious; secondly, a military station should be established at once in the Wallowa Valley, while the agent of the Nez Percé should still strive to settle all that would listen to him upon the reservation; thirdly, that unless in a reasonable time Joseph consented to be removed, he should be forcibly taken with his people and given lands on the reservation; fourthly, if they persisted in overrunning the lands of settlers and disturbing the peace by threats or other-wise, sufficient force should be used to bring them into subjection. And a similar policy was recommended toward all the non-treaty and roaming bands.

The government adopted the suggestions as offered, stationing two companies of cavalry in the Wallowa Valley, and using all diligence in persuading the Indians to go upon the reservation, to which at length, in May 1877, they consented, Joseph and White Bird for their own and other smaller bands agreeing to remove at a given time, and selecting their lands, not because they wished to, but because they must, they understanding perfectly the orders issued concerning them. Thirty days were allowed for removal. On the twenty-ninth day the war-whoop was sounded, and the tragedy of Lost River Valley in Oregon was reenacted along the Salmon River in Idaho.

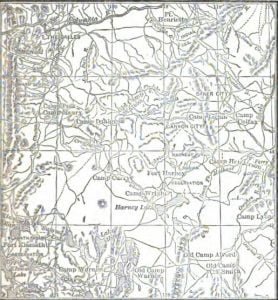

For two weeks Indians of the bands of Joseph, White Bird, and Looking-glass had been gathering on Cottonwood Creek, at the north end of Camas prairie, which lay at the foothills of the Florence Mountains, about sixty-five miles from Lewiston, with the ostensible purpose of removing to the reservation. The white settlements extended along the prairie for considerable distance, the principal one – Mount Idaho – being central. Other settlements on Salmon River were from fifteen to thirty miles distant from Mount Idaho, in a south and southwest direction.

General Howard was at Fort Lapwai, and cognizant of the fact that several hundred Indians, with a thousand horses, were on the border of the reservation without coming upon it. On the afternoon of the last day of grace he directed Captain Perry, whom we have met before in the Modoc country, to have ready a small detachment which should start early on the morning of the 15th to obtain news of the actions and purposes of the Indians. That same evening the general received a letter from a prominent citizen of Mount Idaho, giving expression to his fears that the Indians did not intend to keep faith with him, but took no measures to prevent the execution of their design should the settlers’ fears prove true. In the morning, at the time and in the manner before indicated, the detachment trotted out toward Cottonwood Creek to bring in a report. It returned at noon, having met two reservation Indians excitedly bearing the news that four white men had been killed on John Day Creek, and that White Bird was riding about declaring that the non-treaty Indians would not go on the reservation.

Howard hastened to the agency to consult with Montieth, taking with him the Indian witnesses, who, on being questioned, represented that the white men were killed in a private quarrel. This report necessitated sending other messengers to prove the truth of the Indian statement before the general commanding in Oregon would feel justified in displaying any military force. Late that afternoon they returned, and with them another messenger from Mount Idaho with letters giving a detailed account of a general massacre on Salmon River, 3 and the destruction of all the property of the settlers, including their stock, which, if not driven off, was killed.

There were at Fort Lapwai two companies of cavalry – Captain Perry’s troop F, and Captain Trimble’s troop H – numbering together 99 men. On the night of Friday, 15th, Perry set out with his command, and came upon the Indians in White Bird Canon early Sunday morning. Perry immediately attacked, but with the most disastrous results. In about an hour thirty-four of his men had been killed and two wounded, making a loss of forty per cent of his command. The volunteers, who were chiefly, employed holding the horses of the cavalrymen, sustained but a slight loss. A retreat of sixteen miles to Grangeville was affected, the dead being left upon the field.

In the mean time Howard was using all dispatch to concentrate a more considerable force at Lewiston and Lapwai; the governors of Oregon and Washington were forwarding munitions of war to volunteer companies in their respective commonwealths; and Governor Brayman of Idaho issued a proclamation for the formation of volunteer companies, to whom he could offer neither arms nor pay, but for whom a tele-graphic order from Washington soon provided the former. 4

Not until the 22d were there troops enough brought together, from Wallowa, Walla Walla, and other points, to enable Howard to take the field. At that date 225 men, cavalry, infantry, and artillery, were ready to march. 5 Such defensive measures as were possible were taken to secure the settlements, and the little army commenced a pursuit which lasted from the 23d of June to the 4th of October, with enough of interesting incidents to fill a volume. 6 The first skirmish took place on the 28th, when Howard, who had two days before arrived at White Bird canon to collect and bury Perry’s dead, and been reinforced with about 175 infantry and artillerymen, 7 discovered the Indians in force on the west side of Salmon River not far from opposite the mouth of White Bird Creek. They flaunted their blankets in defiance at the soldiers, dashed down the bare hillside to the river bank, discharged their rifles, and retreated toward Snake River, uninjured by the fire of the troops. Crossing the turbulent Salmon with no other aid than two small rowboats, the army took up the stern chase on the 2d of July. Before starting upon it, Whipple was sent on a march of forty miles toward Kamiah to check the reported preparations for war of the band of young Looking-glass, son of the old chief of that name; but having to rest his horses at Mount Idaho, the chief gave him the go by, and escaped to Joseph, with his people, leaving over 600 horses in the hands of the troops. Whipple then marched back to Cottonwood, where there was a stockade, and scouted to keep the road from Lapwai open for the supply train under Perry.

Meantime Howard was following Joseph through the mountainous region on the west side of the Salmon. When he arrived at Craig’s crossing of the river he learned that the Nez Percé had already recrossed at a lower point, and doubling on their track had re-turned to Camas prairie, and were keeping the cavalry at Cottonwood penned up in the stockade.

One of two scouts sent out to reconnoiter in the direction of Lawyer Creek canon was captured. The other escaping to the quarters of the troops, Whipple despatched to the assistance of the captive ten men under S. M. Rains, guided by the survivor. Before the main command could mount and overtake this detachment, the whole twelve had been ambushed and slain. This was on the 3d of July. On the 4th Whipple marched to meet Perry, and escorted him to Cottonwood without encountering Indians; they were sur-rounding the station with the design of capturing the supplies. Rifle-pits and barricades were constructed, and Gatling guns placed in position. Skirmishing was kept up until nine o’clock that evening, but so inadequate was the force to the situation that the enemy was suffered to move off unmolested toward the Clearwater the following morning. A company of seven-teen volunteers, D. B. Randall captain, coming from Mount Idaho, encountered the enemy within a mile of Cottonwood, and escaped, after a severe engagement, only by the assistance of a company of cavalry from that place, which rescued them after half an hour of exposure to the Indian fire. 8

When Howard heard of the appearance of the Indians on Camas prairie he treated it as the rumor of a raid only, and ordered McConville’s and Hunter’s volunteers to re-enforce Perry, in command at Cottonwood. This force performed escort duty to the wagon conveying the wounded and dead of Randall’s command to Mount Idaho, and returned in time to meet the general when he arrived at Cottonwood via Craig’s ferry, sixteen miles distant from that camp. McConville then proposed to make a reconnaissance in force by uniting four volunteer companies in one battalion, and discover the whereabouts of the Indians. Accordingly, he soon reported them within ten miles of Kamiah, and that he with his battalion occupied a strong position six miles from Kamiah, which Howard requested him to hold until he could get his troops into position, which he did on the 11th, McConville withdrawing on that day 9 to within three miles of Mount Idaho to give protection to that place should the Indians be driven in that direction.

Joseph was at this time in the full flush of success. He had abundance of ammunition and booty. His return to Camas prairie and the reservation grounds had drawn to him about forty of the young warriors of the treaty bands, and twenty or more Coeur d’Alenes, thirsting for the excitement of war. He expected to be attacked, but from the direction of the volunteers, on which side of his camp he had erected fortifications. On the other he had prepared a trail leading up from the Clearwater as a means of escape in case of defeat, and made many caches of provisions and valuable property. The camp lay not far from the mouth of Cottonwood Creek, in a defile of the high hills, which bordered the Clearwater. A level valley of no great width was thus bounded on either side of the river. When Howard placed his guns in position for firing into the enemy’s camp he found that on account of the depth of the canon which protected the Indians he only alarmed instead of hitting them, and they ran their horses and cattle beyond range of the artillery up the stream, on both sides of the Clearwater, getting them out of danger in ten minutes.

Hurrying the guns to another position around the head of a ravine, a distance of a mile and a half, the Indians were found to have crossed the river, and thrown up breastworks ready for battle. Firing commenced here, and Howard’s whole command was posted up and down the river for two miles and a half, in a crescent shape, with supplies and horses in the centre. So active were the Indians that they had almost prevented the left from getting into position, and had captured a small train bringing ammunition, which the cavalry rescued after two packers were killed. Their sharpshooters were posted in every conceivable place, and sometimes joined together in a company and attacked the defenses thrown up by the troops. To these fierce charges the troops replied by counter-charges, the two lines advancing until they nearly met. In these encounters the Indians had the advantage of occupying the wooded skirts of the ravines, by which they ascended from the river bottom to the open country, while the soldiers could only avoid their fire by throwing themselves prone upon the earth in the dry grass, and firing in this position. All the time the voice of Joseph was heard loudly calling his orders as he ran from point to point of his line. And thus the day wore on, and night full, after which, instead of the noise of battle, there was the death-wail, and the scalp-song rising from the Nez Percé camp. The only spring of water was in the possession of the Indians, and was not taken until the morning of the 12th.

Howard then withdrew the artillery from the lines, leaving the cavalry and infantry to hold them, and Captain Miller was directed to make a movement with his battalion, piercing the enemy’s line near the centre, crossing his barricaded ravine, and facing about suddenly to strike him in reverse, using a howitzer. At the moment Miller was about to move to execute this order a supply train, under Captain Jackson, was discovered advancing, and Miller’s battalion was sent to escort it within the lines, which was done with a little skirmishing. This accomplished, he marched slowly past Howard’s front, and turning quickly and unexpectedly, charged the barricades, about two o’clock in the afternoon. After a few moments of furious fighting, the Indians gave way, their defenses were taken, and they fled in confusion, the whole army in pursuit, the Indians retreating to the Kamiah ferry and the trail to the buffalo country by the Lolo fork of the Clearwater.

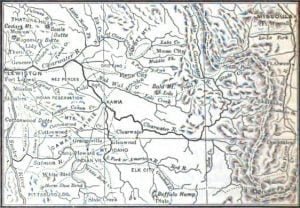

Joseph was not in a condition to leave Idaho at once. He therefore encamped four miles beyond Kamiah, over a range of hills, and sent word to Howard that he wished to surrender. The general had spent the 14th in reconnoitering, and had started on the 15th to march with a column of cavalry twenty miles down the Clearwater and cross at Dunwell’s ferry, hoping the Indians would believe he had gone to Lapwai. But Joseph had been once taken by a strategic movement of that kind, and had no fear of another. He rose equal to the occasion, and by another ruse de guerre induced Howard to hasten to Kamiah to listen to his proposal of surrender. At Kamiah he met, not Joseph, but a headman from his staff, who entertained him with a talk about his chiefs, while one of his people fired on the general from an ambush. This put an end to negotiations; the messenger surrendered with his family, and a few recruits from the neighboring tribes whom the battle of Clearwater had satisfied with war, and Howard again prepared to follow Joseph. 10

It was not until the 17th that the pursuit commenced. On that day Colonel Mason, with the cavalry, the Indian scouts, and McConville’s volunteers, were ordered to make a two days’ march to discover the nature of the trail, and whether the Indians were keeping on toward the buffalo country. They found the trail loading over wooded mountains, where masses of fallen timber furnished frequent opportunities for ambuscades, and on the 18th, when within three miles of Oro Fino Creek, the scouts and volunteers ran into the enemy’s rearguard. Only the tactics of the scouts, by drawing the attention of the attacking party, saved the volunteers from severe loss. Three of the scouts were disarmed, one wounded, and one killed. The enemy sustained a loss of one warrior killed, and two pack animals. After this involuntary skirmish, the troops hastily retreated to Kamiah, where they arrived that night.

The retreat of the cavalry was followed by the return of a small force of the hostile Nez Percé, who, scattering themselves over the country in search of plunder, caused great alarm to the white inhabitants and the reservation Indians. They pillaged and burned some houses on the north fork of the Clearwater, captured 400 horses from the Kamiah, and rejoined their main army. This raid was the last one made by Joseph’s people in Idaho. From this time they pushed on upon their extraordinary exodus, whose objective point became the British possessions.

By the battle of the Clearwater, Joseph’s plans were disarranged. Had he been as successful here as up to this time he had been, all the ill disposed reservation and non-treaty Indians would have gathered to his camp and the war would have been much more disastrous than it was. His loss in battle was twenty-three killed, and between forty and fifty wounded, a large Percéntage out of 300 fighting men. Taken together with the loss of camp equipage and provisions, he had sustained a severe blow, among the severest of which was the desertion of his temporary recruits. Henceforth, he could not hope to increase the number of his followers in his own country. Howard’s loss was thirteen killed, and two officers and twenty-two men wounded.

The last raid of Joseph had also interfered with the plans of Howard, by compelling him to remain in the vicinity of the places threatened until troops then on the way should arrive to protect them. It was his first intention to march his whole command to Missoula City in Montana, by the Mullan road, where he hoped to intercept Joseph as he emerged from the Lolo canon in that vicinity. He had already telegraphed Sherman, then in Montana, and the commanders of posts east of the Bitter Root Mountains, information of Joseph’s exodus by the Lolo trail, and asked for cooperation in intercepting him. On the 30th, two weeks after the Nez Percé started from their camps beyond Kamiah, Howard set out to over take them with a battalion of cavalry, one of infantry, and one of artillery, in all about 700 men, another column having taken the Mullan road a few days earlier.

Captain Rawn of Fort Missoula, on hearing that Joseph was expected to emerge from the Lolo trail into the Bitter Root Valley, erected barricades at the mouth of the canon to prevent it, and hold him for Howard. He had twenty-five regular troops, and 200 volunteers to garrison the stone fort. He committed the error of placing the fortifications too near the exit of the trail, outside of two lateral ravines, of one of which Joseph made use to pass around him and escape, having first consumed four days in pretended negotiations, during which time he made himself master of the topography of the country.

Once in the Bitter Boot Valley, they bartered such things as they had, chiefly horses, with the inhabitants, who dared not refuse, 11 and supplied themselves with what they most needed. 12

There was but a single regiment in western Montana when Howard made his demand for aid. This was the 7th infantry, under Colonel John Gibbon. With drawing all he could from forts Benton, Baker, and Missoula, Gibbon started in pursuit of Joseph soon after he passed the latter post, July 27th. He had seventeen officers, 132 men, and thirty-four citizen volunteers. On the night of the 8th of August he succeeded in creeping close to Joseph’s camp, which was situated on a piece of bottomland on Ruby Creek, a small stream forming one of the head waters of Wisdom River. At daylight on the 9th he attacked, and the Indians being surprised, their camp fell into the hands of the infantry in less than half an hour. But while the soldiers were firing the lodges, the Indians, who had at first run to cover, began pouring upon them in return a leaden shower, which quickly drove them to hiding places in the woods. Fighting continued all day without abatement, the Indians capturing a howitzer and a pack mule laden with ammunition. During the night the Nez Percé escaped, leaving 89 dead on the field, of whom some were women and children. Gibbon had 29 killed and 40 wounded, himself being one of the latter. 13

On the second morning after this battle, Howard came up with a picked escort, and Mason with the remainder of the cavalry arrived late on the 12th. On the 13th Howard took up the pursuit again with the addition to his battalion of fifty of Gibbon’s command. Proceeding southward he was met by the report of eight men killed near the head of Horse prairie the previous night, and 200 horses captured. 14

But on the 15th he received a message from Colonel George L. Shoup, of the Idaho volunteers, informing him that the Indians had recrossed the mountains into Idaho, and surrounded the temporary fortifications at Junction, in Lemhi Valley, containing only forty citizens. Shoup with sixty volunteers had reconnoitered their camp west of Junction, finding them too strong to attack, and called for help. Before Howard could decide to send assistance, another courier informed him that Joseph had made a sudden movement toward the east, leaving the fortified settlers of Lemhi unharmed. Other couriers from the stage company intercepted him on the 16th, and reported the Indians on the road beyond Dry Creek station, in Montana, interrupting travel, and cutting off telegraphic communication, although a guard had been set upon every pass known to the commander of the pursuing army. It was not until the 18th that their camp was discovered near that place.

The following day was Sunday, and Howard, who had religious scruples, went into camp early in the afternoon, about eighteen miles from the encampment of the Nez Percé. The opportunity was a good one for Joseph, who commenced a movement on his own rear a little before sunset, cautiously approaching Howard’s camp, and sending a few skilled horse thieves into it, undertook to divert the attention of the troops by a sudden advance on the pickets, while they stampeded the pack animals. At daylight three companies started in pursuit, and a skirmish ensued, which by continuance became a battle, the remainder of the force joining in. The result was one man killed, six wounded, and the loss of the pack train, which was not recovered. Thus the chase was kept up as far as Henry Lake, where Howard awaited supplies, and rested his men and horses.

As for Joseph, he and his people seemed made all of endurance. They passed on into Wyoming and the national park by the way of the Madison branch of the Missouri. In the lower geyser basin they captured a party of tourists, resting but a short time near Yellowstone Lake. Although a large number of troops were put into the field, namely, six companies of the 7th cavalry under Colonel Sturgis, five of the fifth cavalry under Major Hart, and ten other cavalry companies under Colonel Merritt, to scout in every direction, Joseph again evaded them, and crossed the Yellowstone at the mouth of Clark Fork, September 10th, leaving both Sturgis and Howard in the rear. Sturgis, being re-enforced and sent in fast pursuit, over took the Indians below Clark Fork, and skirmishing with them, killed and wounded several, and captured a large number of horses. Nevertheless, they again escaped, crossing the Musselshell and Missouri Rivers, the latter at Cow Island, the low water steamboat landing for Fort Benton, where they burned the warehouses and stores, and skirmished with a detachment of the 7th infantry engaged in improving the river near Cow Island. On the 23d of September they moved north again toward the British possessions.

When Howard found that the Nez Percé had escaped from Sturgis and himself at Clark Fork, he sent word to Colonel Miles, stationed at the mouth of Tongue River, who immediately organized a force to intercept them. This command left Tongue River barracks on the 18th, reaching the Missouri at the mouth of the Musselshell on the 23d, learning the direction taken by the fugitives on the 25th, and coming up with their camp on Snake Creek, near the north end of Bear Paw Mountains, on the 29th. An attack was made the next morning by three several battalions, the Indians taking refuge, as usual, in the mountain defiles. 15

The first charge cut off from camp all the horses, which were captured, and half the warriors. In the second charge, on the rifle-pits, Captain Hale and Lieutenant Biddle were killed. As soon as the infantry came up, the camp was entirely surrounded, but as it was evident the fortifications could not be taken without heavy loss, Miles contented himself with keeping the enemy under fire until he should surrender. For four days and nights the Indians and the troops kept their positions. A white flag was several times displayed in the Nez Percé camp, but when required to lay down their arms they refused. At length, on the 5th of October, after three and a half months of war, meanwhile being ten weeks hunted from place to place, the Nez Percé were forced to surrender, and General Howard, who had arrived just in time to be present at the ceremony, directed Joseph to give up his arms to Colonel Miles. In the last action Joseph had lost his brother Onicut, a young brave resembling himself in military talent, Looking-glass, another prominent chief, and two head-men, besides twenty-five warriors killed and forty-six wounded. Miles lost, beside the two officers named, twenty-one killed and forty-four wounded. The number of persons killed outside of battle by Joseph’s people was about fifty; volunteers killed in war, thirteen; officers and men of the regular army, 105. The wounded were not less than 120.

To capture 300 warriors, encumbered with their families and stock, required at various times the services of between thirty and forty companies of United States troops, supplemented by volunteers and Indian scouts. The distance marched by Howard’s army from Kamiah to Bear Paw Mountains was over 1,500 miles, a march the severity of which has rarely been equaled, as its length on the warpath has never been surpassed.

The fame of Joseph became wide spread by reason of this enormous outlay of money and effort in his capture, and from the military skill displayed in avoiding it for such a length of time. It only shows that war may be maintained as well by the barbarian as by the civilized man, the best arms and the greatest numbers deciding the contest. When the Nez Percé surrendered, they were promised permission to return to Idaho, and were given in charge of Colonel Miles, to be kept until spring, it then being too late to make the journey. But General Sheridan, in whose department they were, ordered them to Fort Leavenworth, and afterward to the Indian Territory, near the Ponca agency, where they subsequently lived quietly and enjoyed health and comfort. That this was a judicious course to pursue under the circumstances, the behavior of a part of White Bird’s band, who fled to the British possessions after surrendering, and returned to Idaho the following summer, satisfactorily demonstrated. 16

Scarcely was the Percé war over, and Joseph’s people banished, before the territory was again agitated

“The number of Nez Percé, exclusive of Joseph’s followers, still off the reservation in 1878, was 500. The progress of the Percé who remained on tho reservation was rather assisted than retarded by the separation from their fellowship of the non-treaty Indians. Four of the young men from Kamiah were examined by the presbytery of Oregon in 1877, and licensed to preach and teach among their tribe. The membership of the Kamiah and Lapwai churches in 1879 was over 300. They were presided over by one white minister, and one Nez Percé minister named Robert Williams, and contributed of their own means toward tho support of their teachers. That a good deal of their Christianity was vanity, was shown on tho 4th of July, 1879, which day was celebrated by the Kamiah division of the tribe. As the procession formed to march from camp to the place selected for the exercises, those wearing blankets and adhering to aboriginal customs were excluded by the chief and headmen with a contemptuous ‘no Indians allowed.’ Such is the inexorable law of progress – no Indians allowed. In 1880 there were nearly 4,000 acres under cultivation by 170 Nez Percé farmers. Of the 1,200 who lived on the reserve, nearly 900 wore citizens’ dress. In educational matters they were less forward. Notwithstanding the grant by treaty of $6,000 annually for educational purposes, for thirteen years, and notwithstanding missionary efforts, the number who could read in 1880 was 110. The number of children of school age on the reservation was 250, about one fifth of whom attended school. On the 1st of July, 1880, the Stevens treaty expired by limitation, and with it chieftainships and annuities were abolished. In most cases chieftainship has been a source of jealousy to the Indians and danger to the white people, as in the instances of Joseph, White Bird, and others; but tho influence of Lawyer and his successor was probably worth much more than the salary he received, in preserving the peace. When it finally passed away, it was no longer need for that purpose, by the threatening attitude of the Shoshone and allied tribes. The origin of the outbreak was their dissatisfaction as wards of the government. For a few years after their subjugation by generals Crook and Conner the people of Idaho enjoyed a period of freedom from alarms, but in 1871 there was a general restlessness among the tribes of southern Idaho, from the eastern to the western boundary, that boded no good. 17

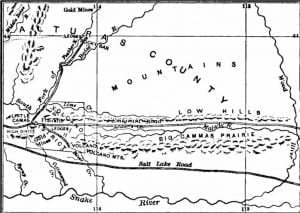

In 1867, while the Shoshone war was yet in progress, Governor Ballard, in his capacity of ex-officio superintendent of Indian Affairs, made an informal treaty (Treaty of 1 June 1868) with the Bannack branch of the Shoshone nation in the eastern part of Idaho, by which they agreed to go upon the Fort Hall reservation before the 1st of June, 1868, provided the land should be set apart forever to them, and that they should be taught husbandry, mechanics, and given schools for their children. The Boise and Bruneau Shoshones were also gathered under an agent and fed through the winter. In 1868 all these Indians were located on the reservation at Fort Hall, some of them straying back to their former homes. A formal treaty was this year made with the Bannacks, by which 1,568,000 acres were set apart for their use and that of kindred tribes. But the ardor with which some of these Indians set to work to learn farming was quenched by the results of the first year’s effort, the grasshoppers destroying a large portion of their crop, in addition to which the government was, as so often happened, behind with its annuities. By the terms of the treaty the Indians were permitted to go to the buffalo grounds, and to dig camas on Big Camas prairie, a part of which was agreed to be set aside for their use whenever they should desire it. 18 Affairs progressed favorably until the death of the principal chief, Tygee, in 1871, when the Indians began to present a hostile front. In 1872 an Indian from the Fort Hall reservation attempted to shoot a farmer at work making hay on the South Boise River. He was seized, but finally liberated by the white man who took him, rather than incur the danger of bringing on a conflict with the tribe. Several similar affairs happened during the summer, and some murders were committed. In 1873 the government ordered the special commission before referred to, of which Shanks was chairman, to investigate causes of trouble in the district of Idaho. These commissioners made a modification of the former treaty with the Bannacks and Shoshones, by which they relinquished their right to hunt on the unoccupied lands of the United States without a written permit from the agent. But no reference was made in the amendments to Camas prairie privileges. Once at Camas prairie, the Indians proceeded under their different chiefs, in detachments, to the Weiser Valley, now being occupied by settlers, where they were met by the Umatillas from Oregon, and where they held a grand fair, horse-races, and exchange of property in the ancient manner. When thus assembled, they numbered, with the Umatillas, about 2,000, and the settlers felt unsafe from their proximity. The superintendency having been taken away from the governor, there was no appeal within the territory, except to the agent at Fort Hall, who justified the giving of passes on account of the meagerness of the commissary department at the agency.

Further trouble was caused in 1874 by an order from the Indian department for the removal of about a thousand Indians – among whom was a band known as the Sheep Eaters, who, five years previous, had been settled in the Lemhi Valley under an agent – to the Fort Hall reservation, these Indians refusing to bo removed. In the following year the order was withdrawn, and a reservation set apart for them containing 100 square miles. In this year, also, an addition was made to the Malheur reservation in Oregon, which was still further enlarged, with new boundaries, in 1876.

But meantime the Modoc war and Joseph’s attitude concerning the Wallowa Valley had their effect in disturbing the minds of the Indians, particularly those of the Oregon Shoshones and the Piutes associated with them. Three or four years of deceitful quiet followed the banishment of the Modocs. When the Nez Percé outbreak occurred, great alarm was felt by the white inhabitants lest the Shoshones and Piutes should join in the revolt. Winnemucca, chief of the Piutes, appeared on the Owyhee with all his warriors; but finding the people watchful, and the military active, they remained quiescent, and Joseph was permitted to do his own fighting. Yet the wide spread consternation which this one band was able to create, and the injury it succeeded in inflicting, encouraged the Indians–many of whom were believers in the Smohallah doctrine of the conquest of the country by the red men – to think that a more combined attack would be successful.

In the summer and autumn of 1877 the Bannacks on the Fort Hall reservation became so turbulent as to require a considerable military force at the agency.

When spring came there was not enough food to keep them all on the reservation, 19 would they have stayed; and being off, in May they commenced shooting white people on Camas prairie, to which, under the treaty, they laid claim equally with the United States. As the settlers kept swine, the camas root was destroyed by them in a wholesale manner very irritating to the Indians.

Their first demonstration, after threatening for some time, was to fire upon two herders, wounding them severely. They next captured King Hill stage station, destroying property and driving off the horses, the men in charge barely escaping. About the same time they appeared on Jordan Creek, demanding arms and ammunition, and captured two freight wagons near Glen’s ferry on Snake River, driving off 100 horses, cutting loose the ferry-boat, and destroying several farm houses from which the families had fled. The settlers of this region fortified themselves at Payne’s ferry, and formed a volunteer company. All over the territory again, an in the preceding summer, business was prostrated, farms were deserted, and citizens under arms.

Again it required time to concentrate troops and find where to strike the Indians. Their movement seemed to be from Fort Hall west along Snake River to the Owyhee. The leader of the hostile Bannacks was Buffalo Horn, one of the Bannack scouts employed in the Nez Percé war, but who was said to have deserted Howard at Henry Lake because he would not be advised by him, and push on to Joseph’s camp, which he insisted could be taken at that time. Evidently he had a taste for fighting which was not satisfied with Howard’s tactics. The chiefs of the Piutes, Winnemucca and Natchez, maintained an appearance of friendship, while Eagan and Oits led the Indians of southwestern Oregon and northern Nevada, Piutes and Malheurs, in their murderous raids. The Umatilla Indians were divided, many of them joining the war-making bands, and others volunteering to fight with the troops. There seemed imminent danger that the uprising would become general, from Utah and Nevada to British Columbia.

The first actual conflict between armed parties was on the 8th of June, when a company of thirty-five volunteers, under J. B. Harper of Silver City, encountered sixty Bannacks seven miles east of South Mountain in Owyhee County. The volunteers wore compelled to retreat, with four white men and two Indian scouts killed, one man wounded, and one missing. 20 On the 11th the stage was attacked between Camp McDermitt and Owyhee, the driver killed, mail destroyed, and some arms and ammunition intended for citizens captured. The Indians on the Malheur reservation in Oregon had left the agency about one week previous, after destroying a large amount of property, going in the direction of Boise. On the 15th Howard, who was near Cedar Mountain in Oregon, announced the main body of the enemy, 600 strong, to be congregated in the valley between Cedar and Steen mountains, and that he was about to move upon them 21 with sixteen companies of cavalry, infantry, and artillery. This movement was commenced on the 23d, the advance, under Bernard, surprising himself and the Indians by running into their rear near Camp Curry the next morning at nine o’clock. The cavalry, four companies, charged the Indians, who rallied and forced Bernard to send for assistance. Not much loss numerically was sustained on either side, the Bannacks, however, losing their leader, Buffalo Horn, which was to them in moral force equivalent to a partial defeat. Before Howard came up, on the 25th, the Indians had disappeared, and left their course to be conjectured by the general. He believed that they would proceed north by Silver Creek and the south branch of John Day River, then up Granite Creek to Bridge Creek, to join the discontented Cayuses and other Indians in that vicinity, when they would make a demonstration still farther north. To provide for this, he sent Colonel Grover to Walla Walla to take command of five companies of cavalry, numbering 240 men, to intercept them, while he remained in their rear with 480 with whom to follow.

Being thus driven, the Indians moved rapidly north. On the 29th they poured into the valley of the south branch of John Day River, surrounding a little company of fifteen home guards, killing one and wounding several. Wherever they went they pillaged and destroyed. Cattle were butchered by the hundreds and left to rot; valuable horses were killed or maimed, and whole herds of sheep mutilated and left to die. The appeals for military aid from beleaguered outlying settlements were as vain as they were piteous. Soldiers could not be spared for guard duty while employed in driving the Indians upon the citizens. Appeals to the governor of Oregon were equally fruitless, as he was not permitted to call for volunteers, and was without arms to distribute to the unarmed settlers, or citizen companies.

On the 2d of July the loyal Umatillas, under their agent, Connoyer, met the enemy 400 strong fighting them all day, killing thirty, with a loss of only two. This prevented a raid, but alarmed the thousand or more of helpless women and children gathered at Pendleton, and a petition for troops was sent to Walla Walla, where General Wheaton had a small force. Wheaton had been advised of the probable approach to the Columbia River of the raiders, and not yet having been joined by Grover, had moved his whole available force of fifty-four men to Wallula, where they were to take a steamboat and patrol the river to observe if any Indians were crossing. But on receiving the call for help from Pendleton, he directed this company to proceed to that place.

All at once calls came from everywhere along the line of settlements, from Des Chutes to the head waters of John Day, showing hostile Indians all along between these points. At Bake Oven, fifty miles from The Dalles, on the 2d of July, they captured a wagon laden with arms and ammunition for the state militia, burned a house, killed one man, and wounded two others. At the same date they were fighting in the vicinity of Canon City and raiding at other points. On the 5th of July Wheaton managed to get possession of a steamer, which he manned with ten ordnance soldiers and ten others, under Captain Kress, who, furnished with a howitzer and Gatling gun, started to patrol the Columbia in the vicinity of Wallula.

On the 6th General Howard was near Granite City, fifty miles south of Pendleton. Halfway between him and that place, at Willow Springs, a company of citizens was attacked, and Captain Sperry and nearly all his command killed or wounded. Hearing how the war was going, if war it could be called which was only a raid feebly resisted, governors Chadwick and Ferry hastened to Pendleton to confer with Howard. A large number of families were sent down the river to The Dalles on a special steamer. A few arms obtained at Vancouver were distributed at that place, and medical service rendered to the sick, of whom there were many, owing to the crowded condition of the town and the mental strain. The Portland militia companies tendered arms and services. The former were accepted, and a consignment of guns made to Governor Brayman of Idaho, arrested at Umatilla by permission, and furnished to the people in that vicinity. Governor Ferry also lent the guns belonging to Washington for use by the citizens of Oregon.

On the 8th of July three companies of cavalry from the department of the Clearwater, under Throckmorton, marching from Lapwai via Walla Walla and Pendleton, made a junction with Howard’s force at Pilot Rock on Birch Creek, a branch of the Umatilla River which skirts the reservation of the Umatilla Indians on the west, and near which, in Fox Valley, the Indian army had received a re-enforcement of disloyal Umatillas, the number of the hostile Indians being now estimated at 1,000. The scouts at this point discovered the Indians in force six miles southwest of Pilot Rock, on Butter Creek, directly on the route to the Columbia, forty miles distant. Strongly posted on the crest of a steep hill, which could only be reached with difficulty by crossing a canon, they awaited the approach of the troops, who skirmished to the top and drove them from their position, capturing some camp material, ammunition, and two hundred broken-down horses. Again they took a position among the pines, which cover the crests of the Blue Mountains, but were soon dislodged by the cavalry under Bernard, and fled still farther into the mountains, where, owing to the roughness of the country, they were not pursued. In this skirmish the Indians sustained slight loss. Their best horses, with their families and property, were between them and the Columbia River, but, as Howard thought, going toward Grand Rond. On the same day several small bands affected a crossing to the north side of the Columbia, driving large bands of horses. Captain Kress with his armed steamboat intercepted one party below Umatilla, and Captain Wilkinson another above that place. The presence of boats at the crossings, notwithstanding Captain Worth, just from San Francisco with his company for this service, had been for several days engaged in seizing boats to prevent the passage of the Indians, showed the complicity of the Columbia River Indians.

Howard having satisfied himself that the principal movement of the marauders was toward Snake River, through the Grand Rond, sent Sandford’s three companies of cavalry and a company of infantry under Miles to follow them. The remainder of his force, under Forsyth, was ordered to Lewiston and Lapwai, to intercept the enemy at the Snake crossing. At Weston, on the 12th, he had a conference with governors Ferry and Chadwick, the latter endeavoring to show that the movement toward Lapwai was premature, and the country in danger if the troops abandoned Oregon at that time. He requested that Throckmorton, who was stationed on Butler Creek, should be ordered to the Umatilla agency. Howard maintained his belief that the Indians were hurrying toward Snake River, and departed the same afternoon for Lewiston by steamer, Chadwick returning to Pendleton. As he did so, he observed signal-fires on the Meacham road over the Blue Mountains, east of Cayuse station, where he had dined that day, and learned that the station had been attacked and burned, the raiding party pursuing the stage from Meacham’s, and attacking another party of travelers, wounding two, one mortally. 22 Turning aside, he reached Pendleton by a different route during the night, finding the towns-people greatly agitated, the Indians being within six miles of that place, on the reservation. The governor had just dispatched the few arms at his command to La Grande, and could do nothing toward arming the citizens. He had hastened a courier after Howard, who did not, however, return; and to give the people confidence, organized a battalion of three hundred men, 23 who ignorantly believed they were to be armed.

In the mean time, however, couriers had overtaken Miles, who was not far from Pendleton with one company of infantry, one of artillery, and Bendire’s cavalry, and who, being joined by a company of volunteers, gave the Indians battle on the morning of the 13th, and drove them in confusion several miles, or until they again escaped to the Blue Mountains. Five Indians were killed, and many wounded, while the loss on the side of the troops was two wounded.

On the same day Wheaton, being informed that Indians were approaching Wallula by the Vansycle canon, sent an order to the cavalry under Forsyth, moving toward Lewiston, to turn back and intercept them. On learning of the invasion of the reservation, Forsyth was ordered to hasten to the assistance of Miles, and Wheaton himself joined the commands at the Umatilla agency on the 15th. Sanford, who had by this time reached La Grande, was ordered by telegraph to return and cooperate with Forsyth’s column, which was in pursuit of the Indians, in attacking the Indian position on the head of McKay Creek, in the mountains, not far from Meacham’s station on the road to La Grande. He found his force too small to meet the Indians congregated at the summit, and retreated to Grand Rond, where, with the assistance of volunteer companies, he kept watch upon the passes into that valley.

On the 16th, while Wheaton was marching toward Meacham’s station, a company of Umatilla Indian volunteers pursuing the raiders killed their chief, Eagan, and brought in his head for identification, together with ten scalps. These sanguinary trophies looked less horrible after finding the bodies of seven teamsters killed along the road to Meacham’s, and the contents of their wagons strewn upon the ground for miles. Again on the 17th the Umatillas, in charge of three white scouts, found the trail of the savages near the east branch of Birch Creek, on the Daly road to Baker City, and battled with them, killing seventeen and capturing twenty-five men, women, and children. Egbert’s command on Snake River had taken an equal number of prisoners. These reverses, and particularly the death of Eagan, dispirited these Indians, who had never shown the persistence or the bravery of the Nez Percé under Joseph. They were soon scattered in small parties, endeavoring to get back to Idaho or Nevada, and the troops were employed for several weeks longer in following and watching them. Little by little they surrendered. On the 10th of August 600 souls were in the hands of the commander of the department in Oregon. But it was some weeks later before depredations by small parties ceased in Idaho. The loss of property was immense. To the marauding parties were added, about the 1st of August, a portion of White Bird’s band of Nez Percés, returned from the British possessions, where they had not met with satisfactory treatment from Sitting Bull, the expatriated Sioux chief, to whom they had fled on the surrender of Joseph. The close of hostilities soon after their arrival rendered them powerless to carry on war, and they became reabsorbed in the Nez Percé nation. The establishment of Camp Howard, near Mount Idaho, and Camp – later fort- Coeur d’Alene, followed the outbreaks here described. After this no serious trouble was experienced in controlling the Indians.

Citations:

- Ind. Aff. Rept, 1874, 57-8; Lewiston Signal, Jane 13, 1874.[

]

- They held that their dead would arise and sweep the white race from the earth. Joseph said that the blood of one of his people who had been slain in a fend, by a white man, would ‘call the dust of their fathers back to life, to people the land in protest of this great wrong. ‘ See Sec. Int. Rept, 608, 45th cong. 2 sess.[

]

- So far as can be gathered from the confused accounts, the first four men killed were on White Bird Creek. They were shot June 14th as they sat playing cards, the Indians being about 20 in number who did the shooting. That same morning they shot Samuel Benedict through the legs while about his farm work. In the evening they went to his house and murdered him, together with a German named August, Mrs Benedict and two children escaping by the aid of an Indian.[

]

- The first company of volunteers was organized at Mount Idaho, where a fortification had been erected. A part of these, under A. Chapman, were with Perry on the 17th. Another company, organized for defense merely, was at Slate Creek. The governor of Idaho ordered to the hostile region, June 20th, a company under Orlando Robbins of Idaho City. A company was organized at Placerville, under J. V. R. Witt. Capt. Hunter of Columbia County, Washington, with 50 volunteers, reported to Howard on the 22nd also Capt. Elliott from the same county with 25; Page of Walla Walla with 20 men, and Williams with 10; and about the same time Capt. McConville of Lewiston with 20 volunteers – making altogether a force, in addition to the regulars, of about 150 men.[

]

- Companies L, Capt. Whipple, and E, Capt. Winters, cavalry; companies D, Capt. Pollock, I, Capt. Eltonhead, E, Capt. Miles, B, Capt. Jocelyn, H, Capt. Haughey, 2lst infantry; and E, Capt. Miller, 4th artillery. Howard’s Rept, in See. War Rept, 1877-8, 120. Capt. Bendire from Camp Harney and Maj. Green from Fort Boise were ordered to the valley of the Weiser to prevent Joseph’s retreat to Wallowa, and to cut off communication between him and the Malheur Shoshones, or Winnemucca’s Piutes.[

]

- A very good narrative of the campaign is contained in a pamphlet of 47 pages by Thomas A. Sutherland, a newspaper writer who accompanied Howard as a volunteer aide-de-camp, entitled Howard’s Campaign against the Nez Percé Indians 1877. Portland, 1878. There is also a partial review of the campaign, written by C. E. S. Wood, in the May number of the Century magazine, 1884, which contains also a portrait of Joseph. My account is drawn chiefly from the different official reports in the Sec, War Rept. 1877-8.[

]

- Companies M, Capt. Throckmorton, D, Capt. Rodney, A, Capt, Bancroft, and G, Capt. Morris, 4th artillery; and E, Capt. Burton, 2l8t infantry. A company of volunteers under Capt. Pago of Walla Walla, scouting along the ridge to the right of the canon, discovered the Indians. This company returned home on the 20th, escorting, together with Perry’s company, a pack train under Leut Miller of the 1st cavalry to Lapwai, for supplies.[

]

- When Randall saw their intention and his situation, he ordered, not a retreat, but a charge through the Indian line, a dash to the creek bottom about a mile from Perry’s camp, there to dismount and return fire, until relief should be sent them from that place. The order was obeyed without faltering and the position gained, but Randall was mortally wounded in the charge. He sat upon the ground and fired until within five minutes of his death. The remaining sixteen made no attempt to run toward camp, trusting in the commander of the troops to be rescued, which rescue was afforded them after an hour of hard fighting. In the mean time B. F. Evans was killed, and A. Bledland, D. H. Houser, and Charles Johnson wounded. The other members of this brave company were L. P. Willmote, J. Searly, James Buchanan, William Beemer, Charles Chase, C. M. Day, Ephraim Bunker, Frank Vancise, George Riggings, A. D. Bartley, H. C. Johnson, and F. A. Fenn.[

]

- There seem to have been the usual jealousies and misunderstandings between the regulars and volunteers. McConville was blamed for leaving his position, which Howard designed him to hold as a part of the enveloping force; out the volunteers certainly did not lack in courage. They were only 90 strong, and were attacked by the Indians on the night of the 10th, losing 50 of their horses. Howard was then across the south branch of the Clearwater, 4 miles beyond Jackson’s bridge, undiscovered by the Indians, who were giving their whole attention to the volunteers, who thus performed a very important duty of diverting observation from the army while getting in position. Being separated from Howard by the river, and haying lost a large number of their horses, it was prudent and good tactics to retire and let the Indians fall into the trap Howard had set for them, near their own camp, and to place himself between the settlements and the Indians. See Howard’s report, in Sec. War Rept, 1877-S, 122; Sutherland’s Howard’s Campaign, 6.[

]

- Sutherland says that Joseph really desired to surrender, and was only deterred by the answer of Howard, that if ho would come in with his warriors they would be tried by a military court, and get justice, with which prospect Joseph was not satisfied. Howard, however, stated in his report that he regarded the proposition to surrender as a ruse to delay movements.[

]

- One merchant, Young of Corvallis, refused to trade with them, closed his store, and dared them to do their worst. Gibbon’s rept, in Sec War Rept, 1877-8, 68. Some, however, of the little town of Stephensville, sold provisions and ammunition to the Indians, and followed them in wagons to trade. Sutherland’s Howard’s Campaign 23.[

]

- This needs some explanation. There were a considerable number of old Indian traders and Hudson’s Bay men in Montana, who could not resist the tempting opportunity to increase their stock from the herds of the fugitive Nez Percé. The U. S. officers complained of this in their reports, without discriminating between this class and American born citizens.[

]

- Of the killed, 6 were volunteers, viz.: L. C. Elliott, John Armstrong, David Morrow, Alvin Lockwood, Campbell Mitchell, H. S. Boatwick. Wounded volunteers: Myron Lockwood, Otto Syford, Jacob Baker, and William Ryan. Gibbon’s rept, in Sec, War Rept, 1877-8, 72.[

]

- This may refer to the same attack by the Nez Percé mentioned in Shoup’s Idaho Territory, MS., 12-13, which says that Joseph’s people met a large train coming over the mountains from Bannack City to Lemhi, and attacking them, drove them into the stockade in Lemhi Valley. They also captured and destroyed 8 wagons, loaded with goods for Shoup & Co. and Frederick Phillips, killing five men and the teams.[

]

- Besides Miles’ own regiment of the 5th infantry, he had a battalion of the 7th cavalry under Captain Hale, and another of the 2d cavalry under Captain Tyler, detailed to his command. Sec. War Rept, 1877-8, 74.[

]

- The number of Nez Percés, exclusive of Joseph’s followers, still off the reservation in 1878, was 500. The progress of the Nez Percés who remained on the reservation was rather assisted than retarded by the separation from their fellowship of the non-treaty Indians. Four of the young men from Kamiah were examined by the presbytery of Oregon in 1877, and licensed to preach and teach among their tribe. The membership of the Kamiah and Lapwai churches in 1879 was over 300. They were presided over by one white minister, and one Nez Percé minister named Robert Williams, and contributed of their own means toward the support of their teachers. That a good deal of their Christianity was vanity, was shown on the 4th of July, 1879, which day was celebrated by the Kamiah division of the tribe. As the procession formed to march from camp to the place selected for the exercises, those wearing blankets and adhering to aboriginal customs were excluded by the chief and head-men with a contemptuous ‘no Indians allowed.’ Such is the inexorable law of progress – no Indians allowed. In 1880 there were nearly 4,000 acres under cultivation by 170 Nez Percé farmers. Of the 1,200 who lived on the reserve, nearly 900 wore citizens’ dress. In educational matters they were less forward. Notwithstanding the grant by treaty of $6,000 annually for educational purposes, for thirteen years, and notwithstanding missionary efforts, the number who could read in 1880 was 110. Tho number of children of school age on the reservation was 250, about one fifth of whom attended school. On the 1st of July, 1880, the Stevens treaty expired by limitation, and with it chieftainships and annuities were abolished. In most cases chieftainship had been a source of jealousy to the Indians and danger to the white people, as in the instances of Joseph, White Bird, and others; but the influence of Lawyer and his successor was probably worth much more than the salary he received, in preserving the peace. When it finally passed away, it was no longer needed for that purpose.[

]

- The language of Norkok, a Shoshone chief, to the agent at the Bannack and Shoshone agency in 1869, on being refused annuity goods off the reservation, was that he supposed the only way to obtain presents was to steal a few horses and kill a few white men.’ Ind. Aff. Rept, 1869, 275.[

]

- Reversion of Indian Treaties, 1873, p. 931. in Sec War Rept, 1878-9, ii. 151.[

]

- It should be explained that the scarcity of food was partly occasioned by the Nez Percé war, which prevented the Indians from hunting as usual. Of this the Bannacks were as well aware as their agent. Congress appropriated $14,000 for their subsistence in 1877, but the deficiency mentioned and the greater number on the reservation caused a partial famine.[

]

- See Silver City Avalanche, June 22, 1878. One of the killed was O. H. Purdy, one of tho discoverers of the Owyhee mines. He insisted, against more cautious counsels, that it was the duty of the company to go to tho assistance of the people of Jordan Valley, which was threatened. By doing so he lost his life, but diverted the Indians from their purpose for the time. Buffalo Horn was supposed to have been killed by Purdy in this skirmish.[

]

- The companies in the field were those of Sandford, Bendire, Sumner, and Carr, under Col Grover, ordered to concentrate at Kinney’s ferry, near old Fort Boise; Bernard’s and Whipple’s, en route from Bruneau River, McGregor, and Bornus to join Bernard; Stewart’s column, consisting of two companies of artillery and five of infantry, at Rhinehart’s ferry on Malheur River; Egbert’s reserve of five companies at Camp Lyon, to be re-enforced by Cochran with one company of infantry. Sec. War Rept, 1878-9, 152.[

]

- George Coggan, proprietor of the St Charles Hotel, Portland, died of his wounds. Alfred Bunker of La Grande and a man named Foster were with him. Foster escaped.[

]

- Chadwick, in Historical Correspondence, MS.; Governor’s Message, Or., 1878, 13-22.[

]