The early history of Idaho has already been given in the former volumes of this series; the modern history of Idaho properly begins with the discovery of the Boise mines, in August 1862, 1 previous to which the movement for a new territory met with little favor. In the spring of 1863 there were four county organizations and ten mining towns, containing, with some outside population, about 20,000 inhabitants, all of whom, except a handful, had come from various parts of the Pacific coast and the western states within the two years following Pierce’s discovery of the Clearwater mines. 2

The leader of the Boise expedition having been killed by Indians while prospecting farther on the stream where gold was found, it received the name of Grimes Creek in commemoration. The party retreated to Walla Walla, where a company was raised, fifty-four strong, to return and hold the mining ground. 3 They arrived at Grimes Creek October 7th, and founded Pioneer City. Others quickly followed, and in November Centreville was founded, a few miles south on the same stream. 4 Placerville, on the head of Granite Creek, contained 300 houses. Buena Vista on Elk Creek and Bannack City 5 on Moore Creek also sprang up in December, and before the first of January between 2,000 and 3,000 persons were on the ground ready for the opening of spring. Up to that time the weather had been mild, allowing wagons to cross the Blue Mountains, usually impassable in winter. Companies of fifty and over, well armed to protect themselves against the Shoshones, at this time engaged in active hostilities, as narrated in my History of Oregon, made the highway populous during several weeks. Supplies for these people poured rapidly into the mines. In the first ten days of November $20,000 worth of goods went out of the little frontier trading post of Walla Walla for the Boise country, in anticipation of the customary rush when new diggings were discovered. Utah also contributed a pack-train loaded with provisions, which the miners found cheaper than those from the Willamette Valley, with the steamboat charges and the middlemen’s profits. 6 Besides, the merchants of Lewiston were so desirous of establishing commerce with Salt Lake that a party was dispatched to old Fort Boise, September 20th, to ascertain if it were practicable to navigate Snake River from Lewiston to that point or beyond. This party, after waiting until the river was near its lowest stage, descended from Fort Boise to Lewiston on a raft, which was constructed by them for the purpose. 7 It was soon made apparent, however, that Lewiston was hopelessly cut off from Salt Lake, and even from the Boise basin, by those formidable barriers alluded to in the previous chapter, of craggy mountains and impassable river canons and falls. The population of Boise was equally interested in means of travel and transportation, and had even greater cause for disappointment when they found that wagons and pack-trains only could be relied upon to convey the commodities in request in every community 300 miles from Umatilla landing 8 on the Columbia to their midst, Umatilla, and not Walla Walla, having become the debouching point for supplies.

Meantime the miners busied themselves making preparations for the opening of spring by locating claims and improving them as far as possible, 9 doing a little digging at the same time, enough to learn that the Boise basin was an extraordinary gold-field as far as it went. Eighteen dollars a day was ordinary wages. Eighty dollars to the pan were taken out on Grimes Creek. Water and timber were also abundant 10 on the stream, which was twelve miles long. On Granite Creek, the headwaters of Placer and Grimes creeks, from $10 to $50, and often $200 and $300, a day were panned out. In the dry gulches $10 to $50 were obtained to the man. Ditches to bring water to them were quickly constructed. The first need being lumber, a sawmill was erected on Grimes Creek during the winter by B. L. Warriner, which was ready to run as soon as the melting snows of spring should furnish the water-power. Early in the spring the second mill was erected near Centreville by Daily and Bobbins, the third begun at Idaho City in May by James I. Carrico, who sold it before completion to E. J. Butler, who moved it to the opposite side of Moore Creek, and had it in successful operation in June. The first steam sawmill was running in July, being built in Idaho City by two men, each known as Major Taylor. It cut from 10,000 to 15,000 feet in ten hours. 11 Thus rapidly did an energetic and isolated community become organized.

The killing of Grimes and other Indian depredations 12 led to the organization of a volunteer company of the Placerville miners in March 1863, whose captain was Jefferson Standifer, a man prominent among adventurers for his energy and daring. 13 They pursued the Indians to Salmon Falls, where they had fortifications, killing fifteen and wounding as many more. Returning from this expedition about the last of the month, Standifer raised another company of 200, which made a reconnaissance over the mountains to the Payette, and across the Snake River, up the Malheur, where they came upon Indians, whose depredations were the most serious obstacle to the prosperity of the Boise basin. Fortifications had been erected by them on an elevated position, which was also defended by rifle-pits. Laying siege to the place, the company spent a day in trying to get near enough to make their rifles effective, but without success until the second day, when by artifice the Indians were induced to surrender, and were thereupon nearly all killed in revenge for their murdered comrades by the ruthless white man. 14

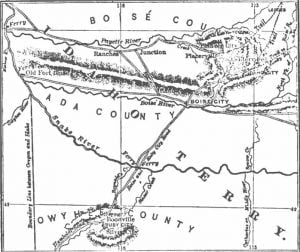

To punish the hostile Indians in Idaho, Fort Boise was established July 1, 1863, by P. Lugenbeel, with two companies of Washington infantry in the regular service. It was situated on the Boise River about forty miles above the old fort of the Hudson’s Bay Company, near the site of the modern Boise City.

Lugenbeel was relieved later in the season by Rinearson of the 1st Oregon cavalry. 15

The summer of 1863 was one of great activity. Early in the season came flattering news of the Beaverhead country lying on the head waters of Jefferson fork of the Missouri River, where claims were held as high as $10,000 and $15,000. On Stinking Water Creek, fifteen miles in length, the diggings were reported to be marvelously rich. Good reports came also from all that region lying between the Rocky and Bitter Root ranges, and the camps on the Missouri to the east of it. About 1,000 miners had wintered in these diggings and two towns, Bannack City on the Beaverhead and Virginia City on another affluent of Jefferson fork, had sprung into existence contemporaneously with the towns in the Boise basin. In the spring of 1863 a bateau load of miners from the upper Missouri left Fort Benton for their homes, taking with them 150 pounds of gold dust.

The principal drawback on the Missouri was the hostility of the Blackfoot Indians, who, notwithstanding their treaty, robbed and murdered wherever they could find white men. Whole parties were killed, and whole pack trains seized.

The immigration of 1863 was not so large as that of the preceding year, and was divided into three columns, one of which was destined for southern Idaho and the mining region of eastern Oregon; another was bound for California; and the third, furnished by the government with a separate escort under Fisk, consisting: of twenty-three wagons and fifty-two men, turned off at Fort Hall for the Salmon River country, failing to reach which they tarried in the Beaverhead mines. Four steamers left St Louis in the spring for the upper Missouri, the Shreveport and Robert Campbell belonging to La Barge & Co., and the Rogers and Alone, owned by P. Choteau & Co. They left St Louis May 9th, and the river being low, were too late to reach Fort Benton. The Shreveport landed her passengers and freight below the mouth of Judith River, 200 miles from that post; the Rogers reached Milk River, 500 miles below the fort; the Alone could not get beyond an old fort of the American Fur Company, twenty-five miles down stream; and the Campbell, drawing only three feet of water, was stopped at Fort Union, 800 miles from her destination, where her passengers and freight were landed, the latter being stored in the fort.

This state of affairs involved much loss and suffering, which was prefaced by the bad conduct of the Sioux, who on one occasion attacked a party of five men whom they invited ashore, killing three and mortally wounding a fourth. The travelers, left at the mercy of the wilderness and the Indians, made their way as best they could to their destinations, some on horse and some afoot. Many miners, expecting to return to their eastern homes by the boats, had gone to Fort Benton from different parts of the country to await their arrival, who now had to turn back to Salt Lake and take passage on stages. To Fort Benton in July had gone 150 wagons to meet the expected boats and convey the freight to the various distribution points. Thirty cents a pound was the lowest rate from Milk River.

Notwithstanding the falling-off in immigration from the cast in 1863, the Boise mines drew between 25,000 and 30,000 to southern Idaho. 16 Improvements were rapid and prices high. To supply the population in the Boise basin required great activity, and to provide for the coming winter exhausted the resources of freighters. Ten or more pack trains arrived daily in July and August, with half that number of wagons, 17 laden with merchandise. No other means of passenger travel than by horses was obtained this season, but the brains were at work which brought about a different state of affairs in the following spring, although the danger from Indians and banditti greatly discouraged stage owners and express men. The Indians stole the horses of the stage companies, and high way men, both white and red, robbed the express messengers. 18

From the abundance of quartz in southern Idaho, and occasional fragments found containing free gold, it was early anticipated that the real future wealth of the territory would depend upon quartz-mining, and miners were constantly engaged in exploring for gold-bearing lodes while they worked the bars and banks of the streams. Their search was rewarded by finding promising ledges on Granite Creek, near the first discovery of placer mines, and on Bear Creek, one of the head waters of the south Boise, where placer claims were also found yielding from $16 to $60 a day to the man. There was a frenzy of excitement following the finding of these quartz lodes, which set men to running everywhere in search of others. In September no less than thirty-three claims of gold and silver quartz mines had been made on the south Boise, all of which promised well. 19 A company was formed to work the Ida Elmore, and a town called Fredericksburg was laid out at this ledge. Other towns, real and imaginary, arose and soon passed out of existence; but Rocky Bar has survived all changes, and Boise City founded at the junction of Moore Creek with Boise River, was destined to become the capital of the territory.

The quartz discoveries on Granite Creek rivaled those in the south Boise district. The first discovery, the Pioneer, had its name changed to Gold Hill after consolidation with the Landon. It was finally owned by an association called the Great Consolidated Boise River Gold and Silver Mining Company, which controlled other mines as well. The poorest rock in the Pioneer assayed over $62 to the ton, and the better classes of rock from $6,000 to $20,000. These assays caused the organization in San Francisco of the Boise River Mining and Exploring Company, which contracted for a ten-stamp mill, to be sent to Boise as soon as completed. 20

Among the richest of the lodes discovered in 1863 was the Gambrinus, which was incorporated by a Portland company. This mine, like others prospecting enormously high, lasted but a short time. It was so rich that pieces of the rock which had rolled down into the creek and become water worn could be seen to glisten with gold fifty feet distant. 21 A town called Quartzburg sprung up on Granite Creek, two miles west of Placerville, as soon as mills were brought into the district, and on the head waters of the Payette, Lake City, soon extinct and forgotten.

But the greatest discovery of the season came from a search for the famous ‘lost diggings’ of the immigration of 1845. In the spring of 1863 a party of twenty-nine set out from Placerville on an expedition to find these much-talked-of never-located mines. 22

Crossing Snake River near the mouth of the Boise, they proceeded, not in the direction supposed to have been travelled by the immigration of 1845, but followed along the south side of Snake River to a considerable stream, which they named Reynolds Creek, after one of their number, where they encamped. Two of the company, Wade and Miner, here ascended a divide on the west, and observed that the formation of the country indicated a large river in that direction. Up to this time nothing was known of the course of the Owyhee River, which was supposed to head in Oregon. It was not certain, therefore, what stream this was. On the following day their explorations lay in the direction of the unknown watercourse. Keeping up the creek, and crossing some very rough mountains, they fell upon the headwaters of another creek flowing toward the unknown river, where they commenced prospecting late in the afternoon of the 18th of May, and found a hundred ‘colors’ to the pan. This place, called Discovery Bar, was six miles below the site of Boonville on Jordan Creek, named after Michael Jordan.

After prospecting ten days longer, locating as much mining ground as they could hold, and naming the district Carson, two other streams. Bowlder and Sinker creeks were prospected without any further discoveries being made, when the company returned to Placerville.

The story of the Owyhee placers caused, as some said, a kind of special insanity, lasting for two days, during which 2,500 men forsook Boise for the new diggings. Many were sadly disappointed. The discovered ground was already occupied, and other good diggings were difficult to find. 23 The distance from Placerville was 120 miles; the mines were far up in the mountains; the road rough, and the country poorly timbered with fir. Nothing like the beautiful and fertile Boise Valley was to be found on the lava-skirted Owyhee. Those who remained at the new diggings were about one in ten of those who so madly rushed thither on the report of the discovery. The rest scattered in all directions, after the manner of gold-hunters; some to return to Boise, and others to continue their wanderings among the mountains. In the course of the summer fresh diggings were found in the ravines away from Jordan Creek; but the great event of the season was the discovery of silver-bearing ledges of wonderful richness on the lateral streams flowing into Jordan Creek. This created a second rush of prospectors to Owyhee, late in the autumn of 1863. 24

Great interest was taken in the Owyhee silver mines, claimed to be the second silver deposit of importance found within United States territory; and much disappointment was felt by Oregonians that this district was included within the limits of the newly organized territory of Idaho, as upon exploration of the course of the Owyhee River, ordered by Governor Gibbs, it was found to be.

The first town laid out on Jordan Creek was Boonville. It was situated at the mouth of a canon, between high and rugged hills, its streets being narrow and crooked. In a short time another town, called Ruby City, was founded in a better location as to space, and with good water, but subject to high winds. Each contained during the winter of 1863-4 about 250 men, while another 500 were scattered over Carson district. In the first six months the little timber on the barren hills was consumed in building and fuel. Lumber cut out with a whip-saw brought forty dollars a hundred feet, and shakes six dollars a hundred. In December a third town was laid off a mile above Ruby, called Silver City.

The general condition of the miners in the autumn was prosperous. Idaho City, called Bannack until the spring of 1864, had 6,000 inhabitants. Main and Wall streets were compactly built for a quarter of a mile, crossed by but one avenue of any importance. Main Street extended for a quarter of a mile farther. Running parallel with Elk Creek were two streets – Marion and Montgomery – half a mile in length. The remainder of the town was scattered over the rising ground back from Elk and Moore creeks. There were 250 places of business, well-filled stores, highly decorated and resplendent gambling-saloons, a hospital for sick and indigent miners, protestant and catholic churches, a theatre, to which were added three others during the winter, 25 three newspapers, 26 and a fire department. Considering the distance of Boise from any great source of supplies or navigable waters, this growth was a marvelous one for eleven months.

Centreville also grew, and was called the prettiest town in the Boise basin. It contained, with its suburbs, 3,000 people. 27 A stage-road was being built from Centreville each way to Placerville and Idaho City by Henry Greathouse, the pioneer of staging in southern Idaho. Placerville had a population of 5,000. It was built like a Spanish town, with the business houses around a plaza in the centre. The population of Pioneer City was 2,000, chiefly Irish, from which it was sometimes called New Dublin. These were the principal towns.

On the 7th of October a festival was given in Idaho City, called Moore’s ball, to celebrate the founding of a new mining state, at which the pioneers present acted as hosts to a large number of guests, who were lavishly entertained. 28 Society in Boise was chaotic, and had in it a liberal mixture of the infernal. The union-threatening democracy of the south-western states was in the majority. Gamblers abounded. Prostitutes threw other women into the shade. Fortunately this condition of things did not last long.

Sickness attacked many a sturdy miner, laying him in his grave away from all his kindred, who never knew where were his bones. Yet not unkindly these unfortunate ones were cared for by their comrades, and the hospital was open to them, with the attendance of a physician and money for their necessities. The Boise News called upon all persons to send in notices of deaths occurring under their observation, and offered free publication, that the friends of the deceased miner might have a chance of learning that his career was ended in the strife for a fortune. 29 To avoid the winter many went east, and into Colorado, Utah, and Oregon, and others would have gone but for the mining law of the district, which required the holders of claims to work them at least one day in seven. 30

Californians were numerous in southern Idaho. 31 Many had been in the Oregon and the Clearwater mines, when the Boise discovery drew them to these diggings. They were enterprising men, and patronized charities and pleasures liberally, many of them being old miners and having no puritan prejudices to overcome. The sport which offered the most novel attractions, while it was unobjectionable from a moral standpoint, was that furnished by the ‘sliding’ clubs of which there were several in the different towns. The stakes for a grand race, according to the rules of the clubs, should not be less than $100 nor more than $2,500, for which they ran their cutters down certain hills covered with snow, and made smooth for the purpose. 32 A circulating library and a literary club also alleviated the irksomeness of enforced idleness in their mountain-environed cities.

The winter was mild in the Boise basin until past the middle of January, when the mercury fell to 25° below zero at Placerville. So little snow had fallen in the Blue Mountains that pack trains and wagons were able to travel between Walla Walla and the mines until February. These flattering appearances induced the stage companies to make preparations for starting their coaches by the 20th of this month; but about this time came the heaviest snow, followed by the coldest weather, of the season, which deferred the proposed opening of stage traffic to the 1st of March. 33 The first attempt was a failure, the snow being so deep on the mountains that six horses could not pull through an empty sleigh. 34

For the same reason, the express from Salt Lake, which was due early in February, did not arrive until in March.

Citations:

- The names of the discoverers were George Grimes of Oregon City, John Reynolds, Joseph Branstetter, D. H. Fogus, Jacob Westenfelten, Moses Splane, Wilson, Miller, two Portuguese called Antoine and Phillipi, and one unknown. Elliott’s Hist. Idaho, 70.[

]

- There was large immigration in 1862, owing to the civil war and to the fame of the Salmon River mines. Some stopped on the eastern flank of the Rocky range in what is now Montana, and others went to eastern Oregon, but none succeeded in reaching Salmon River that year except those who took the Missouri River route. Four steamers from St Louis ascended to Fort Benton, whence 350 immigrants travelled by the Mullan road to the mines on Salmon River. Portland Oregonian, Aug. 28 and 29, 1862. Those who attempted to get through the mountains between Fort Hall and Salmon River failed, often disastrously. Ebey’s Journal, MS., viii. 198. These turned back and went to Powder River. Wm Pur vine, in Or. Statesman, Nov. 3, 1862.[

]

- Among the re-enforcements were J. M. Moore, John Rogers, John Christie, G. J. Gilbert, James Roach, David Thompson, Green and Benjamin White, R. C, Combs, F. Giberson, A. D. Sanders, Wm Artz, J. B. Pierce, and J. F. Guisenberry. Elliott’s Hist, Idaho, 71; Idaho World, Oct. 31, 1864.[

]

- Among this party were Jefferson Standifer, Harvey Morgan, Wm A. Daly, Wm Tichenor, J. B. Reynolds, and Daniel Moffat, who had been sheriff of Calaveras County, Cal.[

]

- This place had its name changed to Idaho City on the discovery that the miners on the east side of the Rocky Mts had named a town Bannack.[

]

- Ebey’s Journal, MS., viii. 127,134; Or. Statesman, Dec. 22, 1862.[

]

- These adventurers were Charles Clifford, Washington Murray, and Joseph Denver. A.P. Ankeny, formerly of Portland originated the expedition. Those who performed it gave it as their opinion that the river could be navigated by steamboats. That same autumn the Spray, a small steamer built by A.P. Ankey, H. W. Corbett and D. S. Baker, in opposition to the O.S.N. Co., ascended the river 15 miles above Lewiston, but could not get no farther. The Tenino also made the attempt, going ten miles and finding no obstacles to navigation in that distance. Lewiston, which as long as the miners were in the Clearwater and Salon Rivers had enjoyed a profitable trade, drawing its goods from Portland by the same steamers which brought the miners thus far on their journey, and retailing them immediately at a large profit, now saw itself in danger of being eclipsed by Walla Walla, which was the source of supply for the Boise basin. Its business men contemplated placing a line of boats on the Snake River to be run as far as navigable. The first important landing was to be at the mouth of Salmon River, forty miles above Lewiston. The design was then to make a road direct to the mines, whereas the travel had hitherto been by the trails through the Nez Percé country. The distance from the mouth of Salmon River by water to Fort Boise was 95 miles, from there to the Fishing Falls of Snake River 90 miles, and from these falls to Salt Lake City 250 miles, making a total distance from Lewiston of 475 miles, nearly half of which it was hoped could be travelled in boats. Such a line would have been of great service to the military department, about to establish a post on the Boise River, and to the im-migration, saving a long stretch of rough road. But the Salmon River Mountains proved impassable, and the Snake River unnavigable, although in the autumn of 1803 a second party of five men, with Molthrop at their head, descended that stream in a boat built at Buena Vista bar, and a company was formed in Portland with the design of constructing a portage through a cañon of the river which was thought impracticable for steamers.[

]

- Wardwell and Lurchin erected a wharf at Umatilla, 30 miles below Wallula, the lauding for Walla Walla, and by opening a new route to the Grand Rond across the Umatilla Indian reservation, diverted travel in this direction.[

]

- Sherlock Bristol, who went to Boise in Dec, says: “I prospected the country, and finally settled down for the balance of the winter and spring on Moore Creek. There we built twenty log houses – mine, Wm Richie’s, and L Henry’s being among the twenty. We made snow-shoes and traversed the valleys and gulches prospecting. As the snow was deep and it was some distance to the creek, some one proposed we should dig a well, centrally located, to accommodate all our settlement. One day when I was absent prospecting the well-digger struck bed-rock down about 18 feet, but found no water; but in the dirt he detected particles of gold. A bucketful panned out $2.75. When I returned at night I could not have bought the claim on which my house was built for $10,000. It proved to be worth $300,000. The whole bench was rich in like manner. My next-door neighbors – the three White brothers – for nearly a year cleaned up $1,500 daily, their expenses not exceeding $300. Bushels of gold were taken out from the gravel beds where Idaho City now stands.’ I have taken this account from a manuscript on Idaho Nomenclature by Sherlock Bristol, who says that Idaho City first went by the name of Moore Creek, after J. Marion Moore, who in 1808 was shot and killed in a dispute about a mine near the South pass. Owyhee Avalanche, in Olympia Wash. Standard, April 18, 1808.[

]

- William Purvine, in Portland Oregonian, Nov. 13, 1862; Lewiston Golden Age, Nov. and 13, 1862.[

]

- Elliot’s Hist, Idaho, 202-3.[

]

- Several prospecting parties had been attacked and a number of men killed by the Shoshones. The Adams immigrant train in 1862 lost 8 persons killed and 10 wounded, besides $20,000 in money, and all their cattle and property. The attack was made below Salmon Falls. S. F. Bulletin, Sept, 27, 1862; Silver Age, Sept. 24, 1862. On the road to Salmon River from Fort Hall the same autumn, William A. Smith, from Independence, Ill., Bennett, and an unknown man, woman, and child, were slain. In March 1862 Isaac Mendell and Jones Brayton prospectors, were killed near Olds’ ferry, on Snake River, below Fort Boise, and others attacked on the Malheur, where a tribe of the Shoshone nation had its headquarters.[

]

- Six feet in height, with broad square shoulders, fine features, black hair, eyes, and moustache, and brave as a lion, is the description of Standifer in McConnell’s Inferno, MS., ii. 2. Standifer was well known in Montana and Wyoming. He died at Fort Steele Sept. 30, 1874. Helena Independent, Nov. 20, 1874.[

]

- Movable defenses were carried in front of the assaulting party, made by letting up poles and weaving in willow rods, filling the interstices with grass and mud. This device proved not to be bullet-proof; and bundles of willow sticks which could be rolled in front of the men were next used and served very well. When the Indians saw the white foe steadily advancing, they sent a woman of their camp to treat, and Standifer was permitted to enter the fort, the Indians agreeing to surrender the property in their possession stolen from miners and others. But upon gaining; access, the white man shot down men, women, and children, only three boys escaping. One child of 4 years was adopted by John Kelly, a violinist of Idaho City, who taught him to play the violin, and to perform feats of tumbling. He was taken to London, where he drew great houses, and afterward to Australia. McConnell’s Inferno, MS., ii 2-4. See also Marysville Appeal, April 11, 1803.[

]

- Fort Boise was built of brown sandstone, and was a fine poet. The reservation was one mile wide and two miles long. H. Ex, Doc. 20, 11, 39th cong. 2nd sess.; Surgeon-Gen’l Circular, 8, 457-60; Bristol’s Idaho Nomenclature, MS., 4.[

]

- Portland Oregonian, July 23 and Aug. 6, 1863;’ Butler’s Life and Times, MS., 2-3. The official census in August was 32,342, of whom 1,783 were women and children. ‘I sold shovels at $12 apiece as fast as I could count them out.’ A wagon-load of cat and chickens arrived in August, which sold readily, at $10 a piece for the cats and $3 for the chickens. But the market was so overstocked with woolen socks in the winter of 1863-4 that they were used to clean guns, or left to rot in the cellars of the merchants.[

]

- A train might be 15 or 50 or 100 animals, carrying from 250 to 400 lbs each. A wagon load was 2,500 or 5,000 pounds. It took 13 days to go from Umatilla to Boise. Therefore, 13 times ten trains and 13 times 5 wagons were continually upon the road, with an average freight of 584,675 pounds arriving every 13 days. Ox-teams were taken off the road as the summer advanced, on account of the dust, which, being deep and strongly alkaline, was supposed to have occasioned the loss of many work-cattle. Horses and mules, whose noses were higher from the ground, were less affected.[

]

- J. M. Sheppard, since connected with the Bedrock Democrat of Baker City, Or., carried the first express to Boise for Tracey & Co. of Portland. Rockfellow & Co. established the next express, between Boise and Walla Walla. After Rockfellow discovered his famous mine on Powder River he sold out to Wells, Fargo, & Co., who had suspended their lines to Idaho the previous year on account of robberies and losses, but who resumed in October, and ran a tri-monthly line to Boise.[

]

- The Ida Elmore, near the head of Bear Creek, the first and most famous of the south Boise quartz mines in 1863, was discovered in June. It yielded in an arastra $270 in gold to the ton of rock, but ultimately fell into the hands of speculators. The Barker and East Barker followed in point of time, ten miles below on the creek. Then followed the Ophir, Idaho, Independence, Southern Confederacy, Esmeralda, General Lane, Western Star, Golden Star, Mendocino, Abe Lincoln, Emmett, and Hibernia. The Idaho assayed, thirty feet below the surface, $1,744 in gold, and $94.86 in silver. Ophir, $1,844 gold and $34.72 silver. Golden Eagle, $2,240 gold, $27 silver, from the croppings. Boise News, Oct. 6, 1863. Rocky Bar was discovered in 1863, but not laid out as a town until April 1864. The pioneers were J. C. Derrick, John Green, F. Settle, Charles W. Walker, M. Graham, W. W. Habersham, H. Comstock (of the Comstock lode, Nev.), A. Perigo, H. O. Rogers, George Ebel, Joseph Caldwell, M. A. Hatcher, L. Hartwig, W. W. Piper, Charles Rogers, S. B. Dilley, D. Fields, Bennett, Foster, Dover, Barney, and Goodrich. Boise Capital Chronicle, Aug. 4, 1869; Boise News, Oct. 20, 1863.[

]

- California Express, Nov. 7, 1863; Boise News, Oct. 27, 1863. The men who located the Pioneer mine were Minear and Lynch, according to the Statement MS., of Henry H. Knapp, who went to Idaho City in the summer of 1863, and who has furnished me a sketch of all the first mining localities, and the early history of the territory. He was one of the publishers of the first paper in the Boise basin, the Boise News, first issued in September 1863. The Portland Oregonian of Sept. 11, 1863, gives the names of the first prospectors of quartz in this region as Hart & Co., Moore & Co., and G. C. Robbins.[

]

- A company was organized to work the Gambrinus, and a mill placed on it in the fall of 1864 by R. C. Coombs & Go. After a year the unprincipled managers engaged in some very expensive and unnecessary labors with a view to freezing out the small owners, and were themselves righteously mined in consequence. Butler’s Life and Times, MS., 8-10. The Pioneer or Cold Hill ledge proved permanent. A mill was put up on it by J. H. Clawson in 1804, and made good returns. After changing hands several times, and paying all who ever owned it, the mine was sold in 1867 to David Coghanour and Thos Mootry for $15,000. Coghanour’s Boise Basin, MS., 1-3. This manuscript has been a valuable contribution to the early history of Idaho, being clear and particular in its statements, and intelligent in its conclusions. David Coghanour was a native of Pa. He went to the Nez Percé mines in the spring of 1862, then to Auburn, Or., in the autumn of the same year. When the Boise excitement was at its height he went to Boise, and earned money making lumber with a whip-saw at 25c per foot. He then purchased some good mining ground on Bummer Hill, above Centreville, from which he took out a largo amount.[

]

- Idaho Lost Diggings Miners[

]

- Henry B. Maize came to Cal. in 1850, returning to Ohio in 1853, and went to the Salmon River mines in 1862, where he wintered. In the spring he went to Boise, and joined some prospectors to the Deadwood Country. While there he heard of the Owyhee discovery, and was among the first to follow the return of the discoverers. His account is that the original twenty-nine had taken pp all the available ground, and made mining laws that gave them a right to hold three claims each, one for discovery, one personal, and one for a friend; and that in fact they had ‘hogged’ everything. He prospected for a time without success, and finally went to the Malheur River; but hearing of the discovery of silver leads, returned to Jordan Creek and wintered there. Maize is the author of Early Events in Idaho, MS., from which I have drawn many facts and conclusions of value in shaping this history of Idaho.[

]

- Maize, in his Early Events, MS., says that the Morning Star was the first ledge discovered, and that it was located by Peter Gimple, S. Neilson, Jack Sammis, and others, and that Oro Fino was next. In this he differs from Purdy, who places the Oro Fino before the Morning Star in point of time; and from Gilbert Butler, who says that in Whiskey Gulch, discovered by B. H. Wade in July, was tho first quartz vein found. Silver City Idaho Avalanche, May 28, 1881. A. J. Sands and Svade Neilson discovered Oro Fine. Purdy also says that the first quartz-ledge was discovered in July, and located by R. H. Wade, and the second, the Oro Fino, in August, A. J. Sands being one of the locators, as he and Neilson were of the Morning Star. Silver City Owyhee Avalanche, May 22, 1875. As often happens, the first discoveries were the richest ever found. Men made $50 a day pounding up the Oro Fino rock in common hand-mortars. It assayed $7,000 in silver and $800 in gold to the ton. A year afterward, when a larger quantity of ore had been tested by actual working, 10 tons of rock were found to yield one ton of amalgam. Walla Walla Statesmen, Nov. 18, 1864. Same of it was marvelously rich – as when 1¼ pounds of rock yielded 9 ounces of silver and gold; and 1 pound yielded $13.60, half in silver and half in gold.[

]

- In point of time they ranked, Idaho theatre 1st, J. L. Allison manager; Forrest 2d, opened Feb. 1864; Jenny Lind 3d, opened in April; Temple 4th. The Forrest was managed by John S. Potter.[

]

- The first newspaper established in the Boise basin was the Boise News, a small sheet owned and edited by T. J. & J. S. Butler, formerly of Red Bluff, Cal., where they published the Red Bluff Beacon. Henry H. Knapp accompanied T. J. Butler, bringing a printing-press, the first in this part of Idaho, and later in use in the office of the Idaho World. Knapp’s Statement, MS., 2. J. S. Butler was born in 1829. He came from Bedford, Ind., to Cal. in 1852, mined for 3 years, and in 1855 started the first newspaper in Tehama County, and which, after 7 years, was sold to Charles Fisher, connected with the Sac. Unions who was killed at Sacramento in 1863 or 1804. Butler married a daughter of Job F. Dye of Antelope rancho, a pioneer of Cal, and went to farming in the Sacramento Valley. His father-in-law took a herd of beef cattle to the eastern Oregon mines in 1802, and sent for him to come up and help him dispose of them. Butler then started a packing business, running a train from Walla Walla to Boise, and recognizing that, with a public of 30,000 or more, there was a field for a newspaper, took steps to start one, by purchasing, with the assistance of Knapp of the Statesman office in Walla Walla, the old press on which the Oregonian was first printed, and which was taken to Walla Walla in 1801. Some other material was obtained at Portland, and the first number of the Boise News was issued Sept. 29, 1863, printing paper costing enormously, and a pine log covered with zinc being used as an imposing-stone, with other inventions to supply lacking material. But men willingly paid $2.50 for one number of a newspaper. The News was independent in politics through a most exciting campaign. Two other journals were issued from its office, representing the two parties in the field – union and democratic – the democrats being greatly in the majority, according to Butler.[

]

- napp’s Statement., MS., 7. This authority describes all the early mining towns, the bread riot, express carrying, and other pioneer matters, in a lucid manner. Knapp came from Red Bluff, and long remained a resident of Idaho.[

]

- This anniversary ball seems to have been repeated in October 1864, Idaho World, in Portland Oregonian, Oct. 31, 1864.[

]

- From Nov. 1864 to Nov. 1865, 125 men were received at the hospital, who had been Injured by the caving of banks, and other accidents incident to mining.[

]

- According to the laws of the district, ‘any citizen may hold 1 creek claim,1 gulch, 1 hill, and 1 bar claim, by location.’ Boise News, Oct. 13, 1863.[

]

- The Boise News of Nov. 21st gives the names of 230 Californians, from Siskiyou County alone, then in the Boise basin.[

]

- A challenge being offered by the Placerville Champion Sliding Club of Boise basin to the Sliding Club of Bannack, the former offering to run their cutter Flying Cloud, carrying 4 persons, from the top of Granite street to Wolf Creek, or any distance not less than a quarter of a mile, was accepted, when in February the Wide West of Bannack ran against the Flying Cloud for the best 2 in 3. The Wide West won the race. Other lesser stakes were lost and won, and the occasion was a notable one, being signalized by unusual festivities, dinners, dancing-parties, etc. One sled on the track, called the French Frigate carried 20 persons, and was the fastest in the basin. Each cutter had its pilot, which was a responsible position. Frequent severe injuries were received in this exciting but dangerous sport. See Boise News, Jan. 30 and Feb. 6, 1804.[

]

- The line from Walla Walla to Boise was owned by George F. Thomas and J. S. Ruckle. (There was a line also to Lewiston, started in the spring of 1804, owned in Lewiston.) It was advertised that they would be drawn by the best horses out of a band of 150, and driven by a famous coachman named Ward, formerly of California, where fine driving had become an art. Geo. F. Thomas of Walla Walla was a stage-driver in Georgia. Going to Cal. in the early times of gold-mining in that state, he engaged in business, which proved lucrative, and became a large stockholder in the California Stage Co., which at one time had coaches on 1,400 miles of road. As vice-president of the company he established a line from Sacramento to Portland, where he went to reside. On the discovery of gold in the Nez Percé country, he went to Walla Walla, and ran stages as the ever changing stream of travel demanded. With J. S. Ruckle be constructed a stage road over the Blue Mountains at a great expense, which was opened in April 1865, and also contributed to the different short lines in Idaho. Idaho City Worlds April 15, 1805. Henry Greathouse, another stage proprietor on the route from the Columbia to Boise, was an enterprising pioneer who identified himself with the interests of this new region. He was, like Thomas, a southern man. With unusual prudence he refrained from expressing his sympathy with the rebellious states, though bis brother, Ridgeley Greathouse, was discovered in S. F. attempting to fit out a privateer, and confined in Fort Lafayette, whence he escaped to Europe.[

]

- In northern Idaho the snow and cold were excessive. Daniel McKinney, P. K. Young, M. Adams, John Murphy, and M. Sol. Keyes, who left Elk City Oct. 6th with a small pack train for the Stinking Water mines on Jefferson fork of the Missouri, were caught in a snowstorm, and wandered about in the mountains until the 1st of Dec., when they were discovered and relieved. Walla Walla Statesman Feb. 13, 1804. Several similar incidents occurred in different parts of the territory.[

]