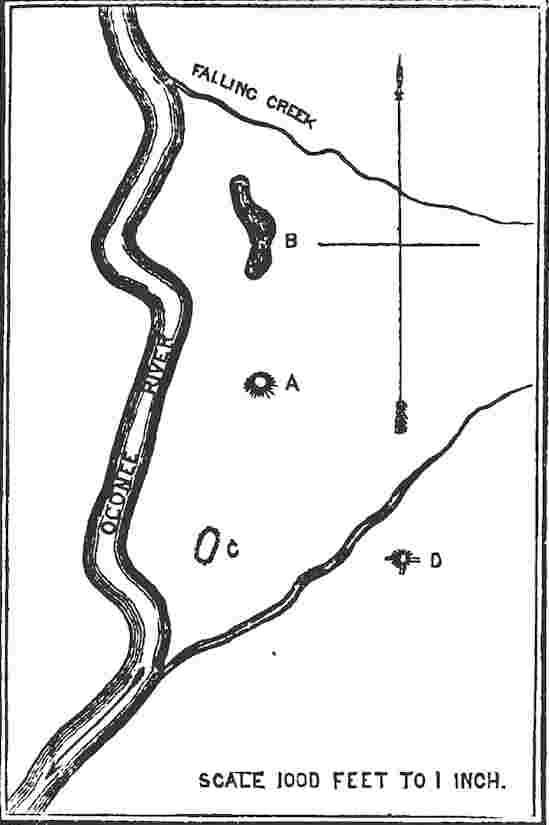

About a mile and a half north of the Fontenoy Mills, in Greene County, Georgia, and located on the left bank of the Oconee River, are three tumuli surrounded by traces of extensive and long-continued inhumations. The largest (A) is situated rather more than 100 yards east of the river, and rises about 40 feet above the level of the valley. In general outline it may be described as a truncated cone. Its apex diameters, measured north and south, and east and west, were respectively, 65 and 68 feet. At the base, however, the flanks are extended in the direction of the east and west to such a degree that there is a difference of 35 feet between the base-diameters running north and south, and east and west; the former being 133 feet and the latter 168 feet. At the center of the top may be seen a circular depression, some 20 feet wide and 2 feet deep.

Toward the north the face of this tumulus is quite precipitous. When first observed by the European, this monument was covered with a growth of trees as dense and apparently as old as that of the circumjacent lowlands. When the neighboring fields were cleared, this mound was also denuded of its vegetation and cultivated, its rich surface yielding generous harvests both of corn and cotton. Although now overgrown with brambles and small trees, which materially retarded minute inspection, it appeared quite probable from the scars on the surface of the valley in the immediate vicinity, that some severe freshet years ago impinged upon the northern base of this mound and carried away a considerable portion of its northern flank.

Rather more than 100 yards to the north of this tumulus, and trending to the northwest, is an irregularly shaped excavation (B), at present from 10 to 15 feet deep and partially filled with water, from which the earth used in the construction of these tumuli was obtained.

As yet no attempt has been made to open the large mound, but against its eastern face the overflowing waters of the Oconee at one time dashed, wearing it away for some distance and leaving there a perpendicular front of 10 feet or more. Here were disclosed human bones, the skeletons of dogs, and large beads made of the columns of the Strombus gigas. If this partial revelation be accepted as indicative of the general contents of the tumulus, it should be classed as a huge grave-mound. We decline, however, adopting this conclusion without further information. It may be that the remains and relics then unearthed belonged to later and secondary interments. Instances of this sort, as we well know, are of frequent occurrence.

Two hundred yards to the south is an elliptical grave-mound (0), not more than 4 feet high, but covering a considerable area. This structure, in the direction of its major axis, is about 150 feet long. Its minor axis is two-thirds less. The surface and neighborhood abound with human bones, shreds of pottery, fragments of pipes, shell-beads, muscleshells, and various other relics. Across a shallow lagoon, and 250 yards southeast of the large tumulus, is a third mound (D), well preserved, 10 feet high, and quite level at the top. In every direction, except where it looks toward the north, its sides slope gently. Having been constantly cultivated for many years, this structure has encountered no inconsiderable waste. At the base its north and south diameter was 100 feet. Measured at right angles, the other diameter was 88 feet. Similar measurements across the top indicated 50 feet and 40 feet. To the east, west, and south, are traces of spurs or graded ways for easy ascent.

This mound occupies a central and commanding position in the middle of a fertile alluvial field of fifty acres. Although its contents are unknown, we conceived the impression that it was designed as an elevation for a chieftain’s lodge, since the Spanish historians mention the existence of artificial tumuli erected for this purpose. Around the base, and for a considerable distance on every hand, are traces of primitive occupancy, all persuading us of the fact that, in former times, this tumulus was surrounded by the dwellings f people who had here fixed their home.

The space adjacent to the large tumulus (A), to the extent of some four acres, appears to have been largely, if not exclusively, dedicated to the purposes of sepulture. Every freshet which sweeps over this area uncovers human skeletons, disposed in every direction only a few feet below the surface. So thoroughly and frequently has this territory been torn by freshets that it has lost its original level, and now exhibits on every hand heaps of broken pottery, quantities of human bones, and fragments of various articles of use, sport, and ornament. The freshet of 1840 was the first, so far as we can learn, which in a marked manner invaded the precincts of this ancient burial ground. Upon the subsidence of the waters many were attracted to the spot by the multitude of terra-cotta vessels, human bones, shell-beads, pipes, discoidal stones, grooved axes, celts, and other objects of primitive manufacture. One gentleman collected nearly a quart of pearls which had been perforated and worn as beads. The plantation Negroes supplied themselves with clay pipes then unearthed. In the possession of not a few of them were seen strong clay vessels, thence obtained, which they used for boiling soap. Large calumets and other objects of special interest were secured by the curious and carried to their homes, where, for a season, they formed matter for speculation and idle talk, and in the end were either lost or broken. Subsequent inundations have brought to light similar proofs of sepulture and early manufacture, but this treasure-house has been so often visited and so carefully searched that its present yield falls far short of that which was encountered when the Harrison freshet invaded this place of the dead.

It is a sad fact that the denudation of the banks of these southern streams and the destruction of extensive forests in reducing wild lands to a state of cultivation have proved the proximate causes of serious injury to, and often of the total demolition of, many prominent and interesting aboriginal structures.

On the right bank of the Oconee River, about a mile and a half above its confluence with the Appalachee River, situated in the low grounds of the plantation of Mr. Thomas P. Saffold, is a circular earth mound some 20 feet high, covering about the eighth of an acre. The sides are sloping, as in the case of other conical mounds along the line of this river, but the peculiarity which distinguishes it from its companions is that around the apex stout earth walls were raised to the height of several feet, thus causing a depressed or guarded top.

Near the banks of the Appalachee River, in Morgan County, may still be seen occasional artificial pits, some 4 feet in depth and 6 feet or more in diameter. Upon removing the debris of leaves and earth with which they are filled, their bottoms and sides indicate the influence of long continued and intense fires. Fragments of pottery also occur in them. It would seem that they constituted a sort of rude oven in which the Indians baked their clay vessels.

We might multiply instances of tumuli still extant in the valleys of the Oconee and its tributaries, but having already described and figured those in East Macon and its vicinity, 1 enough has probably been said to convey an intelligent idea of the aboriginal monuments of this section.

Citations:

- Antiquities of the Southern Indians, &c., p. 158 et seq., New York, 1873.[↩]

Discover more from Access Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.