The Miami Circle was discovered in 1998 during excavation for the construction of a luxury condominium at Brickell Point in Downtown Miami near the Miami River and Biscayne Bay. 1 The developer, Michael Baumann, tore down an existing apartment complex in 1998. Prior to initiating construction of the new tower, he was required to retain archaeologists to carry out a brief field survey the site by the city’s historic preservation ordinance. However, Baumann did not do this until pressured by the Miami-Dade Historic Preservation Division Director, Bob Carr, pressured him to do so. The survey was actually carried out by municipal employees, volunteers and members of the Archaeological & Historical Conservancy. Afterward, the 2.2 acre site was designated Miami Midden No. 2 or 8DA1212. 2

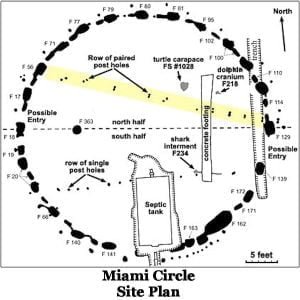

During what was intended to be a brief survey consisting of random post hole size pits, a volunteer came upon an ancient hole cut into the soft Oolithic limestone bedrock that was rectangular and about two feet deep. 3 More holes were discovered after Carr directed further exploration. A pattern appeared. A surveyor, Ted Riggs, suspected that the team had found a circular pattern, 38 feet (12 m) in diameter. He did this by calculating the center associated with the uncovered holes. Using CADD, he then projected the probable locations of the other holes. Excavation soon revealed that there were 24 holes forming a perfect circle.

The structure is currently estimated to have been built at some time between 0 AD and 300 AD. 4 This estimate is based on radiocarbon dating of decomposed wood particles found inside several of the holes in the limestone. Opponents of this interpretation argue that old wood particles had washed into the slots and that the Miami Circle was much younger.

When the public first heard about the discovery of a 38 feet diameter circle at Brickell Point and its radiocarbon date, there were claims that it was “an Olmec or Maya city.” Even professional archaeologists publicly stated that there were no other permanent towns north of Mexico at that time and so the Miami Circle was the oldest known permanent habitation in North America. That is not correct. Poverty Point in northern Louisiana was begun around 1,600 BC. By 0 AD there were many permanent agricultural villages in northern and central Georgia.

There are hundreds of smaller holes within and outside the main structure. 5 Artifacts, typical of a maritime hunter-gatherer culture, such as the Tekesta Indians of southeast Florida, were found in the soil above the stone foundation. The only exceptions were three stone axes, said to be made from basalt, a type of igneous stone not found in Florida.

Dr. Jacqueline Dixon, of the University of Miami, reported that the basalt was likely from the region of Macon, Georgia, some 600 miles away. 6 There is no basalt around Macon, but there are deposits farther north near Atlanta. Basalt is a very poor material for making axes and wedges because it fractures easily and cannot be worked to a fine blade. Dixon based her comments on the similarity of the axes to those found at Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon. However, those axes were greenstone and they came from the region around Dahlonega, GA, 140 miles north of Macon in the Georgia Mountains. 7 During Pre-European times, the Dahlonega area exported greenstone wedges and axed to Native peoples throughout eastern North America.

Professional and public controversies

From the moment of its discovery, the Miami Circle has been the focus of much controversy, both within the archaeological community and in the Miami political scene. Florida anthropologists generally agree that the structure was built by the Tekesta Indians, mainly because the artifacts associated with fishing, that were found near the stone surface of the Miami were typical of the Tekesta. 8 However, such primitive tools are really typical of the entire Caribbean Basin and northern South America. There is also the same problem as the wood particles. They could have been washed onto the site of the Miami Circle after it was abandoned by its builders.

In 2012 geologists discovered that in 539 AD a massive comet or asteroid struck the Atlantic Ocean between Florida and the Bahamas. 9 The resulting tsunami was gigantic, much bigger than the ones in Sumatra in 2005 and Japan in 2011. The wall of water would have first swept the shores of Biscayne Bay clean of all small objects. Then the retreating waters would have deposited other artifacts.

Michael Baumann, the developer, initially offered to cut out the section of rock containing the holes and relocate them outside the area where he planned to build the condominium. 10 He was backed by the City of Miami’s mayor, Joe Carollo. Two local governments were involved, the City of Miami and the government of Miami-Dade County. The Historic Preservation Commission was employed by the county government, while the building plan review was carried out by employees of the city government.

A plan to move the circle was formally proposed to the City of Miami. 11 Joshua Billig, stonemason of Rockers Stone and Supply, was contracted to relocate the stone slab. Billig terminated the contract on February 14, 1999, after becoming convinced the circle should not be moved.

Public opposition grew. An alliance of individuals and groups that included historic preservationists, architects, archaeologists, Native Americans and students protested. 12 Their complaint was that the removal could potentially destroy one of the most archaeologically significant finds in North America. This claim may or may not be true, but it caught the national media’s attention. The Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation made a donation of $25,000 to fund further exploration of the site, which continued until February 1999.

The City of Miami issued grading and construction permits for the Brickell Point condominium during the last week of January 1999. 13 The Dade Heritage Trust filed a lawsuit against the city’s actions on January 31, 1999. It sought an injunction against further construction. The Trust’s pro-bono attorney, Gary Held, arranged for an emergency hearing at the home of Circuit Court Judge Thomas Wilson.

The basis for the Heritage Trust’s lawsuit was that the developer had not obtained required approval in the form of a certificate of appropriateness from the City’s Historic and Environmental Preservation Board. In laymen’s language, the city was obligated to obey the laws of the State of Florida and the United States, but had not. This was a legal fact and normally would have prevented any construction at sites owned by people with less political influence than Baumann.

At the hearing in Judge Wilson’s home, the developer and the City were represented by counsel. 14 This put the Historic Preservation Division in the awkward position of the municipal government challenging the staff of the county government. During arguments presented by both sides, the attorney for the Heritage Trust admitted that that his client was not prepared to post a bond to support the injunction request.

Judge Wilson denied the motion for temporary injunction. His judgment was in violation of the National Historic Preservation Act and the laws of the State of Florida. A citizen or group of citizens, are not required to post bond, when the complaint is that a government agency is in violation of state or federal law. Nevertheless, Baumann agreed to postpone construction on the site for thirty days while the archeologists finished their work.

Typical of the general disdain of North Florida archaeologists toward South Florida archaeological sites, the famous University of Florida archaeologist, Dr. Jerald Milanich, publicly announced his concern that the cuts in the bedrock were of 20 th century origin. 15 He stated that the holes were dug during the construction of the original apartment building. An excavation for a septic tank was aligned perfectly at the edge of the circle. He suggested that the circle could be nothing more than a sink for the sewage from the septic tank. Milanich’s high profile statement caused political backlash outside of South Florida that almost scuttled plans to preserve the site. .

To refute this claim, John Ricicek of the Miami-Dade Historic Preservation Commission identified two factors that Milanich had not considered. 16 There was a terracotta outflow from the pit of the former septic tank that would not require a sink being excavated in the rock. The architectural plans for the apartment complex clearly showed a sewage overflow to the south that connected with the Miami River.

Ricciek also cited the original analysis of the pits by the Florida Geological Survey. It described a later of calcite on the holes. The bedrock that had been cut out to lay the tank had little or no such calcite or “duricrust.” This fact proved a considerable age difference between the septic tank construction and the circle of holes.

The public controversy over the Miami Circle generated exaggerated interpretations of the site’s importance. It is called “the oldest permanent village” on the Eastern Coast by Wikipedia. 17 Web sites pronounce it the 3,000 year old capital of an ancient Tekesta civilization or a 6,000 year old stone temple. 18 Others suggest that it was a temple built by the survivors of Atlantis. Imaginative artists have painted renderings of the supposed structure to resemble Greek temples or extraterrestrial spaceports. In reality, the Miami Circle can currently be described only as a circle created by 24 big holes carved in bedrock that was occupied at some point by indigenous peoples.

Whatever the conflicting opinions that archaeologists, architects, historic preservationists and the general public might have about age and purpose of the Miami Circle, there is one undeniable fact. The indigenous peoples of northern South America were building round, communal structures long before they appeared in southeastern North America. Also, several branches of the Arawaks in Cuba and certain other Caribbean islands, built round communal buildings. There were probably Arawaks or South Americans living in Cuba when the Miami Circle was built. Miami could have well been the first leg of their journey to settle in North America. .

Preservation and protection

Baumann had agreed to a 30-day delay in construction at the hearing. 19 An alliance of County Mayor for Miami-Dade, Alex Penelas and other historic preservations requested that the Miami-Dade County Commission to file a lawsuit to take ownership of the property. The Commission approved this action on 18 February. Judge Richard Feder ordered a temporary injunction against the City of Miami and the property that prohibited construction on the site.

Baumann agreed to sell the property to the county government. 20 However, he initially demanded $50 million in compensation. The asking price was eventually lowered to $26.7 million, when he realized that the county could initiate imminent domain legal procedures. Baumann made a profit of 18.2 million minus his pre-development costs. In an unprecedented move, the State of Florida Preservation 2000 Land Acquisition Program purchased the site from Baumann for that sum in November 1999. The commission utilized both state matching funds and donations from various foundations and private citizens.

On February 5, 2002, the Miami Circle site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. 21 History-Miami, then known as the Historical Museum of Southern Florida, signed a 44-year lease of the site in March 2008, and currently offers tours of the site. It was declared a National Historic Landmark on January 16, 2009. 22 A waterfront park managed by History-Miami opened in 2011. 23 The Miami Circle itself remains buried to protect it, while an audio tour and several panels describing it are available.

Artifacts recovered from the Miami Circle site are stored and on display at History-Miami Museum. 24 It is the official repository for all archaeological materials recovered in Miami-Dade County. On February 3, 2014, the Miami Herald reported additional postholes had been excavated in Downtown Miami. 25 This is further evidence of a significant indigenous community in what is now Downtown Miami. The new site contains multiple house sites marked by post holes in the limestone bedrock. They have been dated to about 600 AD.

Was the preservation cost justified?

The special attention given the Miami Circle in the media and by preservation agencies is indicative of a major problem with the current situation of Native American archeological sites in southern Florida. The large town sites around Lake Okeechobee and near the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River receive minimal care and attention. Only one is even on the National Register of Historic Places. None are federal or state owned historic parks. Politics are involved. Native American town sites in northern Florida, which are in easy driving distance of the state capitol in Tallahassee receive far more publicity and protection than the nationally significant town sites with multiple earthworks in South Florida.

The state and citizens of Florida spend $26.7 million to acquire the Brickell Point property. At least $2 million more has spent in consultants, studies, legal fees, staff time and landscaping of the park. All of this was done to protect a circle of pits in limestone about 38 feet in diameter, plus several hundred small post holes around the circle. Much of what is said about the Miami Circle is speculation. It may be factual and may not be. The environs of the Miami Circle must be thoroughly studied by archaeologists before speculations can become facts.

Meanwhile, extremely large archaeological zones in the remainder of South Florida, which are of very important national significance are being neglected or even developed. In retrospect, a solution should have been adopted that preserved the immediate environs of the Miami Circle, but allowed partial development of the site. In an imminent domain hearing, this solution would have negated Baumann’s demand to make a $20 million profit prior to any construction occurring.

Citations:

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- MiamiCircle.org web site. “Miami Circle Facts.”[

]

- MiamiCircle.org web site. “Miami Circle Facts.”[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- Thornton, Richard, The Search for Fort Caroline, Raleigh: Lulu Publishing, 2015; pp. 87, 90, 214.[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- Thornton, Richard, “Tsunami on South Atlantic Coast.” People of One Fire; June 6, 2014.[

]

- Cass, D: “Vicious Circle,” Metropolis, 108, 113, November 1999.[

]

- Cass, D: “Vicious Circle,” Metropolis, 108, 113, November 1999.[

]

- Cass, D: “Vicious Circle,” Metropolis, 108, 113, November 1999.[

]

- Cass, D: “Vicious Circle,” Metropolis, 108, 113, November 1999.[

]

- Cass, D: “Vicious Circle,” Metropolis, 108, 113, November 1999.[

]

- 15. Millanich, Gerald T. “American Scene: Much Ado About a Circle.” AIA Journal Online (Archaeology.org). Volume 52 Number 5, September/October 1999.[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- Ancient Labyrinths. “The Miami Stone Circle.”[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- “The Miami Circle.” Wikipedia.[

]

- “Interior Secretary Kempthorne Designates 9 National Historic Landmarks in 9 States“. Department of the Interior. 2009-01-16.[

]

- “Interior Secretary Kempthorne Designates 9 National Historic Landmarks in 9 States“. Department of the Interior. 2009-01-16.[

]

- Weiner, Jacquelyn (28 October 2010). “12 years after discovery, Miami Circle due December opening“. Miami Today.[

]

- Prieto, Alison (2008-03-14). “Historical Museum signs sublease with State of Miami to manage the Miami Circle.” Historical Museum of Southern Florida.[

]

- Viglucci, Andres. (2014-02-03). “Prehistoric village found in downtown Miami“. Miami Herald.com.[

]