Pima Indians (‘no,’ in the Nevome dialect, a word incorrectly applied through misunderstanding by the early missionaries. 1. As popularly known, the name of a division of the Piman family living in the valleys of the Gila and Salt in south Arizona. Formerly the term was employed to include also the Nevome, or Pimas Bajos, the Pima as now recognized being known as Pimas Altos (‘Upper Pima’ ), and by some also the Papago. These three divisions speak closely related dialects. The Pima call themselves A’â’tam, the people.

Pima Tribe History

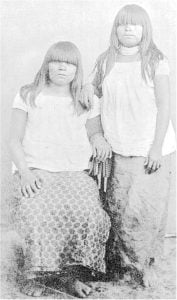

Pima Women, Wearing Pima Shirts

According to tradition the Pima tribe had its genesis in the Salt River valley, later extending it’s settlements into the valley of the Gila; but a deluge came, leaving a single survivor, a specially favored chief named Cího, or Sóho, the progenitor of the present tribe. One of his descendants, Sivano, who had 20 wives, erected as his own residence the now ruined adobe structure called Casa Grande (called Sivanoki, ‘house of Sivano’) and built numerous other massive pueblo groups in the valleys of the Gila and Salt. The Sobaipuri, believed to have been a branch of the Papago, attributed these now ruined pueblos, including Casa Grande, to people who had come from the Hopi, or from the north, and recent investigations tend to show that the culture of the former inhabitants, as exemplified by their art remains, was similar in many respects to that of the ancient Pueblos. Sivano’s tribe, says tradition, became so populous that emigration was necessary. Under one of the sons of that list a large body of the Pima settled in Salt River Valley, where they increased in population and followed the example of their ancestors of the Gila by constructing extensive irrigation canals and reservoirs and by building large defensive villages of adobe, the remains of which may still be seen.

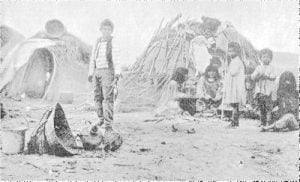

The Pima attribute their decline to the rapacity of foreign tribes from the east, who came in three bands, destroying their pueblos, devastating their fields, and killing or enslaving many of their inhabitants. Prior to this, however, a part of the tribe seceded from the main body and moved south, settling in the valleys of Altar, Magdalena, and Sonora Rivers, as well as of adjacent streams, where they became known as Pimas Bajos or Nevome, and Opata. The others descended from the mountains whence they had fled, resettled the valley of the Salt, and again tilled the soil. They never rebuilt the substantial adobe dwellings, even though needed for defense against the always aggressive Apache; but, humbled by defeat, constructed dome-shaped lodges of pliable poles covered with thatch and mud, and in such habitations have since dwelt. The names applied to the Pima by the Apache and some other tribes furnish evidence that they formerly dwelt in adobe houses. Early in the 19th century the Pima were joined by the Maricopa, of Yuman stock, who left their former home at the mouth of the Gila and on the Colorado owing to constant oppression by the Yuma and Mohave. Although speaking distinct languages the Maricopa and Pima have since dwelt together in harmony. They intermarry, and their general habits and customs are identical.

Pima Tribe Culture

Pima Huts showing Home Life and Utensils

How much of the present religious belief of the Pima is their own is not known, though it is not improbable that the teachings of Kino and other missionaries in the 17th and 18th centuries influenced more or less their primitive beliefs. They are said to believe in the existence of a supreme being, known as the “Prophet of the Earth,” and also in a malevolent deity. They also believe that at death the soul is taken into another world by an owl, hence the hooting of that bird is regarded as ominous of an approaching death. Sickness, misfortune, and death are attributed to sorcery, and, as among other Indians, medicine-men are employed to overcome the evil influence of the sorcerers. Scarification and cauterization are also practiced in certain cases of bodily ailment.

Marriage among the Pima is entered into without ceremony and is never considered binding. Husband and wife may separate at pleasure, and either is at liberty to marry again. Formerly, owing to contact with Spaniards and Americans, un-chastity prevailed to an inordinate degree among both sexes. Polygamy was only a question of the husband’s ability to support more than one wife. The women performed all the labor save the hunting, plowing, and sowing; the husband traveled mounted, while the wife laboriously followed afoot with her child or with a heavily laden burden basket, or kiho, which frequently contained the wheat reaped by her own labor to be traded by the husband, often for articles for his personal use or adornment.

The Pima have always been peaceable, though when attacked, as in former times they frequently were by the Apache and others, they have shown themselves by no means deficient in courage. Even with a knowledge of firearms they have only in recent years discarded the bow and arrow, with which they were expert. Arrowheads of glass, stone, or iron were sometimes employed in warfare. War clubs of mesquite wood also formed an important implement of war; and for defensive purposes an almost impenetrable shield of rawhide was used. The Pima took no scalps. They considered their enemies, particularly the Apache, possessed of evil spirits and did not touch them after death. Apache men were never taken captive; but women, girls, and young boys of that tribe were sometimes made prisoners, while on other occasions all the inhabitants of a besieged Apache camp were killed. Prisoners were rarely cruelly treated; on the contrary they shared the food and clothing of their captors, usually acquired the Pima language, and have been known to marry into the tribe.

Agriculture by the aid of irrigation has been practiced by the Pima from prehistoric times. Each community owned an irrigation canal, often several miles in length, the waters of the rivers being diverted into them by means of rude dams; but in recent years they have suffered much from lack of water owing to the rapid settlement of the country by white people. Until the introduction of appliances of civilization they planted with a dibble, and later plowed their fields with crooked sticks drawn by oxen. Grain is threshed by the stamping of horses and is winnowed by the women, who skillfully toss it from flat baskets. Wheat is now their staple crop, and during favorable seasons large quantities are sold to the whites. They also cultivate corn, barley, beans, pumpkins, squashes, melons, onions, and a small supply of inferior short cotton. One of the principal food products of their country is the bean of the mesquite, large quantities of which are gathered annually by the women, pounded in mortars or ground on metates, and preserved for winter use. The fruit of the saguaro cactus (Cereus giganteus) is also gathered by the women and made into a syrup; from this an intoxicating beverage was formerly brewed. As among most Indians, tobacco was looked upon by the Pima rather as a sacred plant than one to be used for pleasure. Formerly they raised large herds of cattle in the grassy valleys of the upper Gila. The women are expert makers of water-tight baskets of various shapes and sizes, decorated in geometric designs. They also manufacture coarse pottery, some of which, however, is well decorated. Since contact with the whites their native arts have deteriorated.

The Pima are governed by a head chief, and a chief for each village. These officers are assisted by village councils, which do not appoint representatives to the tribal councils, which are composed of the village chiefs. The office of head-chief is not hereditary, but is elected by the village chiefs. Descent is traced in the male line, and there are five groups that bear some resemblance to gentes, though they exert no influence on marriage laws, nor is marriage within the group, or gens, prohibited 2. These five groups are Akol, Maam, Vaaf, Apap, and Apuki. The first three are known as Vultures or Red People, the other two as Coyotes or White People. They are also spoken of respectively as Suwuki Ohimal (‘Red Ants’) and Stoam Ohimal (‘White Ants’) .

The Pima language is marked by the constant use of radical reduplication for forming the nominal and verbal plural. It is also distinguished by a curious laryngeal pronunciation of its gutturals, which strangers can imitate only with great difficulty.

Pima Pueblos and Settlements

The Pima within the United States are gathered with Papago and Maricopa on the Gila River and Salt River reservations. The Pima population was 3,936 in 1906; in 1775 Father Garcés estimated the Pima of the Gila at 2,500. Their sub-divisions and settlements have been recorded as follows, those marked with an asterisk being the only ones that are not extinct in 1904. Some of the names are possibly duplicated.

- Agua Escondida(?)

- Agua Fria(?)

- Aquitun

- Aranca

- Arenal(?)

- Arivaca(?)

- Arroyo Grande

- Bacuancos

- Bisani

- Blackwater*

- Bonostac

- Busanic

- Cachanila(?)

- Casa Blanca*

- Cerrito

- Cerro Chiquito

- Chemisez

- Chupatak

- Chutikwuchik*

- Chuwutukawutuk

- Cocospera

- Comac

- Estancia

- Gaibanipitea(?)

- Gutubur

- Harsanykuk*

- Hermho*

- Hiatam*

- Hormiguero(?)*

- Huchiltchik*

- Hueso Parado

- Imuris

- Judac

- Kainit

- Kamatukwucha*

- Kawoltukwucha*

- Kikimi

- Kookupvansik

- Mange

- Merced

- Nacameri

- Napeut

- Ocuca

- Oquitoa

- Ormejea

- Oskakumukchochikam

- Oskuk*

- Peepchiltk*

- Pescadero

- Petaikuk

- Pintados(?)

- Pitac(?)

- Potlapiguas

- Remedios

- Rsanuk*

- Rsotuk*

- Sacaton*

- San Andres Coata

- San Fernando

- San Francisco Ati

- San Francisco de Pima

- San Serafin

- Santan*

- Santos Angeles

- Saopuk*

- Sepori

- Shakaik*

- Statannyik*

- Stukamasoosatick

- Sudacson

- Tatsituk*

- Taumaturgo

- Tucson (mixed)

- Tucubavia

- Tuhuscabors

- Tutuetac(?)

- Uturituc

- Wechurt*

Citations: