Peter McQueen, at the head of the Tallase warriors; High Head Jim, with the Autaugas, and Josiah Francis, with the Alabamas, numbering in all three hundred and fifty, departed for Pensacola with many pack-horses. On their way they beat and drove off all the Indians who would not take the war talk. The brutal McQueen beat an unoffending white trader within an inch of his life, and carried the wife of Curnells, the government interpreter, a prisoner to Pensacola. The village of Hatchechubba was reduced to ashes.

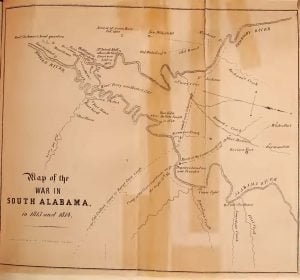

The inhabitants of the Tombigby and the Tensaw had constantly petitioned the governor for an army to repel the Creeks, whose attacks they hourly expected. But General Flournoy, who had succeeded Wilkinson in command, refused to send any of the regular or volunteer troops. The British fleet was seen off the coast, from which supplies, arms, ammunition and Indian emissaries were sent to Pensacola and other Spanish ports in Florida. Everything foreboded the extermination of the Americans in Alabama, who were the most isolated and defenseless people imaginable. Determined, however, to protect themselves to the best of their means and abilities, they first sent spies to Pensacola to watch the movements of the Indians there under McQueen, who returned with the report that the British agents were distributing to them ample munitions of war. Colonel James Caller ordered out the militia, some of whom soon rallied to his standard in the character of minute volunteers. He marched across the Tombigby, passed through the town of Jackson, and by the new fort upon the eastern line of Clarke, and from thence to Sisemore’s Ferry, upon the Alabama, where, on the western bank, he bivouacked for the night. The object of the expedition was to attack the Indians as they were returning from Pensacola. The next morning Caller began the crossing of the river to the east side, which was effected by swimming the horses by the side of the canoes. It occupied much of the early part of the day. When all were over the march was resumed in a southeastern direction to the cow-pens of David Tait, where a halt was made. Here Caller was reinforced by a company from Tensaw Lake and Little River, under the command of Dixon Bailey, a half-breed Creek, a native of the town of Auttose, who had been educated at Philadelphia under the provisions of the treaty of New York of 1790. Bailey was a man of fine appearance, unimpeachable integrity, and a strong mind. His courage and energy were not surpassed by those of any other man. The whole expedition under Caller now consisted of one hundred and eighty men, in small companies. Two of these were from St. Stephens, one of which was commanded by Captain Bailey Heard, and the other by Captain Benjamin Smoot and Lieutenant Patrick May. A company, from the county of Washington, was commanded by Captain David Cartwright. In passing through Clarke county, Caller had been re-enforced by a company under Captain Samuel Dale and Lieutenant Girard W. Creagh. Some men had also joined him, commanded by William McGrew, Robert Caller, and William Bradberry. The troops of the little party were mounted upon good frontier horses, and provided with rifles and shotguns, of various sizes and descriptions. Leaving the cow-pens, Caller marched until he reached the wolf-trail, where he bivouacked for the last night. The main route to Pensacola was now before them.

In the morning, the command was re-organized, by the election of Zachariah Philips, McFarlin, Wood, and Jourdan, to the rank of major, and William McGrew, lieutenant-colonel. This unusual number of field officers was made to satisfy military aspirations. While on the march, the spy company returned rapidly, about 11 o’clock in the forenoon, and reported that McQueen’s party were encamped a few miles in advance, and were engaged in cooking and eating. A consultation of officers terminated in the decision to attack the Indians by surprise. The command was thrown into three divisions–Captain Smoot in front of the right, Captain Bailey in front of the centre, and Captain Dale in front of the left. The Indians occupied a peninsula of low pine barren, formed by the windings of Burnt Corn Creek. Some gently rising heights overlooked this tongue of land, down which Caller charged upon them. Although taken by surprise, the Indians repelled the assault for a few minutes, and then gave way, retreating to the creek. A portion of the Americans bravely pursued them to the water, while others remained behind, engaged in the less laudable enterprise of capturing the Indian pack horses. Caller acted with bravery, but, unfortunately, ordered a retreat to the high lands, where he intended to take a strong position. Seeing those in advance retreating from the swamp, about one hundred of the command, who had been occupied, as we have stated, in securing Indian effects, now precipitately fled, in great confusion and terror, but, in the midst of their dismay, held on to the plunder, driving the horses before them. Colonel Caller, Captain Bailey, and other officers, endeavored to rally them in vain. The Indians rushed forth from the swamp, with exulting yells, and attacked about eighty Americans, who remained at the foot of the hill. A severe fight ensued, and the whites, now commanded by Captains Dale, Bailey and Smoot, fought with laudable courage, exposed to a galling fire, in open woods, while McQueen and his warriors were protected by thick reeds. The latter, however, discharged their pieces very unskillfully. Captain Dale received a large ball in the breast, which, glancing around a rib, came out at his back he continued to fight as long as the battle lasted. At length, abandoned by two-thirds of the command, while the enemy had the advantage of position, the Americans resolved to retreat, which they did in great disorder. Many had lost their horses, for they had dismounted when the attack was made, and now ran in all directions to secure them or get up behind others. Many actually ran off on foot. After all these had left the field three young men were found still fighting by themselves on one side of the peninsula, and keeping at bay some savages who were concealed in the cane. They were Lieutenant Patrick May, of North Carolina, now of Greene county, Alabama, a descendant of a brave revolutionary family; a private named Ambrose Miles and Lieutenant Girard W. Creagh, of South Carolina. A warrior presented his tall form. May and the savage discharged their guns at each other. The Indian fell dead in the cane; his fire, however, had shattered the lieutenant’s piece near the lock. Resolving also to retreat, these intrepid young men made a rush for their horses, when Creagh, brought to the ground by the effects of a wound which he received in the hip, cried out, “Save me, lieutenant, or I am gone!” May instantly raised him up, bore him off on his back and placed him in the saddle, while Miles held the bridle reins. A rapid retreat saved their lives. Reaching the top of the hill they saw Lieutenant Bradberry, a young lawyer of North Carolina, bleeding with his wounds, and endeavoring to rally some of his men. The Indians, reaching the body of poor Ballad, took off his scalp in full view, which so incensed his friend Glass that he advanced and fired the last gun upon them.

The retreat was continued all night in the most irregular manner, and the trail was lined, from one end to the other, with small squads, and sometimes one man by himself. The wounded traveled slowly, and often stopped to rest. It was afterwards ascertained that only two Americans were killed and fifteen wounded. Such was the battle of Burnt Corn, the first that was fought in the long and bloody Creek war. The Indians retraced their steps to Pensacola for more military supplies. Their number of killed is unknown. Caller’s command never got together again, but mustered themselves out of service, returning to their homes by various routes, after many amusing adventures. Colonel Caller and Major Wood became lost, and wandered on foot in the forest, causing great uneasiness to their friends. When General Claiborne arrived in the country he wrote to Bailey, Tait and McNac, respectable half-breeds, urging them to hunt for these unfortunate men. They were afterwards found, starved almost to death and bereft of their senses. They had been missing fifteen days. 1

General Ferdinand Leigh Claiborne, the brother of the ex-Governor of the Mississippi Territory, was born in Sussex County, Virginia, of a family distinguished in that commonwealth from the time of Charles I. On the 21st November 1793, in his twentieth year, he was appointed an ensign in Wayne’s army on the Northwestern frontier. He was in the great battle in which that able commander soon after defeated the Indians, and for his good conduct, was promoted to a lieutenancy. At the close of the war he was stationed at Richmond and Norfolk, in the recruiting service, and subsequently was ordered to Pittsburg, Forts Washington, Greenville and Detroit, where he remained with the rank of captain and acting adjutant general until 1805, when he resigned and removed to Natchez. He was soon afterwards a member of the Territorial legislature, and presided over its deliberations. We have already seen how active he was in arresting Aaron Burr, upon the Mississippi river, at the head of infantry and cavalry. On the 8th March 1813, Colonel Claiborne was appointed brigadier-general of volunteers, and was ordered by General Wilkinson to take command of the post of Baton Rouge. In the latter part of he was ordered by General Flournoy to march with his whole command to Fort Stoddart, and instructed to direct his principal attention to “the defense of Mobile.”

On the 30th July, General Claiborne reached Mount Vernon near the Mobile River with the rear guard of his army, consisting of seven hundred men, whom he had chiefly sustained by supplies raised by mortgages upon his own estate. 2 The quartermaster at Baton Rouge had only provided him with the small sum of two hundred dollars. He obtained, from the most reliable characters upon the eastern frontier, accurate information in regard to the threatened invasion of the Indians, an account of the unfortunate result of the Burnt Corn expedition, and a written opinion of Judge Toulmin, respecting the critical condition of the country generally. It was found that alarm pervaded the populace. Rumors of the advance of the Indians were rife, and were believed. In Clarke County, in the fork of the rivers, a chain of rude defenses had hastily been constructed by the citizens, and were filled to overflowing with white people and Negroes. One of these was at Gullett’s Bluff, upon the Tombigby, another at Easley’s station, and the others at the residences of Sinquefield, Glass, White and Lavier. They were all called forts. Two blockhouses were also in a state of completion, at St. Stephens.

The first step taken by Claiborne was the distribution of his troops, so as to afford the greatest protection to the inhabitants. He despatched Colonel Carson, with two hundred men, to the Fork, who arrived at Fort Glass without accident. A few hundred yards from that rude structure he began the construction of Fort Madison. He sent Captain Scott to St. Stephens with a company, which immediately occupied the Old Spanish blockhouse. He employed Major Hinds, with the mounted dragoons, in scouring the country, while he distributed some of the militia of Washington County for the defense of the stockade. Captain Dent was despatched to Oaktupa, where he assumed the command of a fort with two blockhouses within a mile of the Choctaw line. 3

Citations:

- Conversations with Dr. Thomas G. Holmes, of Baldwin county, Alabama, the late Colonel Girard W. Creagh, of Clarke, and General Patrick May, of Greene, who were in the Burnt Corn expedition.[↩]

- Upon the conclusion of the Creek war General Claiborne returned to Soldier’s Retreat, his home, near Natchez, shattered in constitution, from the exposure and hardships of the campaigns and died suddenly at the close of 1815. The vouchers for the liberal expenditures which he made were lost and his property was sold.[↩]

- MS. papers of General F. L, Claiborne.[↩]