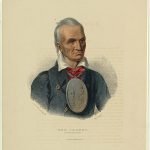

Sa-go-you-rvat-ha, or Keeper awake

1756 – 1830

About the year 1820, Count D., a young French nobleman, who was making a tour in America, visited the town of Buffalo. Hearing of the fame of Red Jacket, and learning; that his residence was but seven miles distant, he sent him word that he was desirous to see him, and that he hoped the chief would visit him at Buffalo, the next day Red Jacket received the message with much contempt, and replied, “tell the young man that if he wishes to see the old chief, he may find him with his nation, where other strangers pay their respects to him; and Red Jacket will be glad to see him.” The count sent back his messenger, to say that he was fatigued by his journey, and could not go to the Seneca village; that he had come all the way from France to see Red Jacket, and after having put himself to so much trouble to see so great a man, the latter could not refuse to meet him at Buffalo. “Tell him,” said the sarcastic chief, “that it is very strange he should come so far to see me, and then stop short within seven miles of my residence.” The retort was richly merited. The count visited him at his wigwam, and then Red Jacket accepted an invitation to dine with the foreign traveler at his lodgings in Buffalo. The young nobleman declared that he considered Red Jacket a greater wonder than the Falls of Niagara. This remark was the more striking, as it was made within view of the great cataract. But it was just. He who made the world, and filled it with wonders, has declared man to be the crowning work of the whole creation.

It happened, during the revolutionary war, that a treaty was held with the Indians, at which Lafayette was present. The object was to unite the various tribes in amity with America. The majority of the chiefs were friendly, but there was much opposition made to it, more especially by a young warrior, who declared that when an alliance was entered into with America, he should consider the sun of his country had set for ever. In his travels through the Indian country, when last in America, it happened at a large assemblage of chiefs, that Lafayette referred to the treaty in question, and turning to Red Jacket, said, “pray tell me, if you can, what has become of that daring youth who so decidedly opposed all our propositions for peace and amity? Does he still live? and what is his condition?” “I, myself, am the man,” replied Red Jacket; “the decided enemy of the Americans, so long as the hope of opposing them successfully remained, but now their true and faithful ally until death.”

During the war between Great Britain and the United States, which commenced in 1812, Red Jacket was disposed to remain neutral, but was overruled by his tribe, and at last engaged heartily on our side, in consequence of an argument which occurred to his own mind. The lands of his tribe border upon the frontier between the United States and Canada. “If the British succeed,” he said. “they will take our country from us; if the Americans drive them back, they will claim our land by right of conquest.” He fought through the whole war, displayed the most undaunted intrepidity, and completely redeemed his character from the suspicion of that unmanly weakness with which he had been charged in early life; while in no instance did he exhibit the ferocity of the savage, or disgrace himself by any act of outrage towards a prisoner or a fallen enemy. His, therefore, was that true moral courage, which results from self-respect and the sense of duty, and which is a more noble and more active principle than that mere animal instinct which renders many men insensible to danger. Opposed to war, not ambitious of martial fame, and unskilled in military affairs, he went to battle from principle, and met its perils with the spirit of a veteran warrior, while he shrunk from its cruelties with the sensibility of a man, and a philosopher.

Red Jacket was the foe of the white man. His nation was his God; her honor, preservation, and liberty, his religion. He hated the missionary of the cross, because he feared some secret design upon the lands, the peace, or the independence of the Seneca. He never understood Christianity. Its sublime disinterestedness exceeded his conceptions. He was a keen observer of human nature; and saw that among white and red men, sordid interest was equally the spring of action. He, therefore, naturally enough suspected every stranger who came to his tribe of some design on their little and dearly prized domains; and felt towards the Christian missionary as the Trojan priestess did towards the wooden horse of the Greeks. He saw, too, that the same influence which tended to reduce his wandering tribe to civilized habits, must necessarily change his whole system of policy. He wished to preserve the integrity of his tribe by keeping the Indians and white men apart, while the direct tendency of the missionary system was to blend them in one society, and to bring them under a common religion and government. While it annihilated paganism, it dissolved the nationality of the tribe. In the wilderness, far from white men, the Indians might rove in pursuit of game, and remain a distinct people. But the district of land reserved for the Seneca, was not as large as the smallest county in New York, and was now surrounded by an ever-growing population impatient to possess their lands, and restricting their hunting-grounds, by bringing the arts of husbandry up to the line of demarcation. The deer, the buffalo, and the elk were gone. On Red Jacket’s system, his people should have followed them; but he chose to remain, and yet refused to adopt those arts and institutions which alone could preserve his tribe from an early and ignominious extinction.

It must also be stated in fairness, that the missionaries are not always men fitted for their work. Many of them have been destitute of the talents and information requisite in so arduous an enterprise; some have been bigoted and over zealous, and others have wanted temper and patience. Ignorant of the aboriginal languages, and obliged to rely upon interpreters to whom religion was an occult science, they doubtless often conveyed very different impressions from those which they intended. ” What have you said to them?” inquired a missionary once, of the interpreter who had been expounding his sermon. “I told them you have a message to them from the Great Spirit,” was the reply. ” I said no such thing,” cried the missionary; “tell them I am come to speak of God, the only living and True God, and of the life that is to be hereafter-well, what have you said?” “That you will tell them about Mani-to and the land of spirits.” “Worse and worse!” exclaimed the embarrassed preacher; and such is doubtless the history of many sermons which have been delivered to the bewildered heathen.

There is another cause which has seldom failed to operate in opposition to any fair experiment in reference to the civilization of the Indians. The frontiers are always infested by a class of adventurers, whose plans of speculation are best promoted by the ignorance of the Indian; who, therefore, steadily thwart every benevolent attempt to enlighten the savage; and who are as ingenious as they are busy, in framing insinuations to the discredit of those engaged in benevolent designs towards this unhappy race.

Whatever was the policy of Red Jacket, or the reasons on which it was founded, he was the steady, skilful, and potent foe of missions in his tribe, which became divided into two factions, one of which was called the Christian, and the other the Pagan party. The Christian party in 1827 outnumbered the Pagan and Red Jacket was formally, and by a vote of the council, displaced from the office of Chief of the Seneca, which he had held ever since his triumph over Corn Plant. He was greatly affected by this decision, and made a journey to Washington to lay his griefs before his Great Father. His first call, on arriving at Washington, was on Colonel M’Kenney, who was in charge of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. That officer was well informed, through his agent, of all that had passed among the Seneca, and of the decision of the council, and the cause of its displacing Red Jacket. After the customary shaking of hands, Red Jacket spoke, saying, “I have a talk for my Father.” “Tell him,” answered Colonel M’Kenney, ” I have one for him. I will make it, and will then listen to him.” Colonel M’Kenney narrated all that had passed between the two parties, taking care not to omit the minute incidents that had combined to produce the open rupture that had taken place. He sought to convince Red Jacket that a spirit of forbearance on his part, and a yielding to the Christian party the right, which he claimed for himself, to believe as he pleased on the subject of religion, would have prevented the mortifying result of his expulsion from office and power. At the conclusion of this talk, during which Red Jacket never took hi? keen and searching eye off the speaker, he turned to the interpreter, saying, with his finger pointing in the direction of his people, and of his home, “Our Father has got a long eye!” He then proceeded to vindicate himself, and his cause, and to pour out upon the black coats the phials of his wrath. It was finally arranged, however, that he was to go home, and there, in a council that was directed to be convened for the purpose, express his willingness to bury the hatchet, and leave it to those who might choose to be Christians, to adopt the ceremonies of that religion, whilst for himself, and those who thought like him, he should claim the privilege to follow the faith of his fathers. Whereupon, and as had been promised him at Washington, the council unanimously replaced him in the office of chief, which he held till his death. This happened soon after. It is due to him to state, that a cause, which has retarded the progress of Christianity in all lands lying adjacent to Christian nations, naturally influenced his mind. He saw many individuals in Christendom who were worse than Pagans. He did not know that few of these professed to be Christians, and that a still smaller number practiced the precepts of our religion; but judging them in the mass, he saw little that was desirable in the moral character of the whites, and nothing inviting in their faith. It was with these dews, that Red Jacket, in council, in reply to the proposal to establish a mission among his people, said, with inimitable severity and shrewdness, ” Your talk is fair and good. But I propose this. Go, try your hand in the town of Buffalo, for one year. They need missionaries, if you can do what you say. If in that time you shall have done them any good, and made them any better, then we will let you come among our people.”

A gentleman, who saw Red Jacket in 1820, describes him as being then apparently sixty years old. He was dressed with much taste, in the Indian costume throughout, but had not a savage look. His form was erect, and not large; and his face noble. He wore a blue dress, the upper garment cut after the fashion of a hunting Shirt; with blue leggings, very neat moccasins, a red jacket, and a girdle of red about his waist. His eye was fine, his forehead lofty and capacious, and his bearing calm and dignified. Previous to entering into any conversation with our informant, who had been introduced to him under the most favorable auspices, he inquired, “What are you, a gambler, (meaning a land speculator,) a sheriff, or a black coat?” Upon ascertaining that the interview was not sought for any specific object other than that of seeing and conversing with himself, he became easy and affable, and delivered his sentiments freely on the subject which had divided his tribe, and disturbed himself, for many years. He said that “he had no doubt that Christianity was good for white people, but that the red men were a different race, and required a different religion. He believed that Jesus Christ was a good man, and that the whites should all be sent to hell for killing him; but the red men having no hand in his death, were clear of that crime. The Savior was not sent to them, the atonement not made for them, nor the Bible given to them, and therefore the Christian religion was not intended for them. If the Great Spirit had intended they should be Christians, he would have made his revelation to them as well as to the whites; and not having made it, it was clearly his will that they should continue in the faith of their fathers.”

The whole life of the Seneca chief was spent in vain endeavors to preserve the independence of his tribe, and in active opposition as well to the plans of civilization proposed by the benevolent, as to the attempts at encroachment on the part of the mercenary. His views remained unchanged and his mental powers unimpaired, to the last. The only weakness, incident to the degenerate condition of his tribe, into which he permitted himself to fall, was that of intoxication. Like all Indians, he loved ardent spirits, and although his ordinary habits were temperate, he occasionally gave himself up to the dreadful temptation, and spent several days in succession, in continual drinking.

The circumstances attending his decease were striking, and w shall relate them in the language of one who witnessed the facts which he states. For some months previous to his death, time had made such ravages on his constitution as to render him fully sensible of his approaching dissolution. To that event he often adverted, and always in the language of philosophic calmness. He visited successively all his most intimate friends at their cabins, and conversed with them upon the condition of the nation, in the most impressive and affecting manner. He told them that he was passing away, and his counsels would soon be heard no more. He ran over the history of his people from the most remote period to which his knowledge extended, and pointed out, as few could, the wrongs, the privations, and the loss of character, which almost of themselves constituted that history. “I am about to leave you,” said he, ” and when I am gone, and my warnings shall be no longer heard, or regarded, the craft and avarice of the white man will prevail. Many winters have I breasted the storm, but I am an aged tree, and can stand no longer. My leaves are fallen, my branches are withered, and I am shaken by every breeze. Soon my aged trunk will be prostrate, and the foot of the exulting foe of the Indian may be placed upon it in safety; for I leave none who will be able to avenge such an indignity. Think not I mourn for myself. I go to join the spirits of my fathers, where age cannot come; but my heart fails, when I think of my people, who are soon to be scattered and forgotten.” These several interviews were all concluded with detailed instructions respecting his domestic affairs and his funeral.

There had long been a missionary among the Seneca, who was sustained by a party among the natives, while Red Jacket denounced “the man in dark dress,” and deprecated the feud by which his nation was distracted. In his dying injunctions to those around him, he repeated his wishes respecting his interment. “Bury me,” said he, “by the side of my former wife; and let my funeral be according to the customs of our nation. Let me be dressed and equipped as my fathers were, that their spirits may rejoice in my coming. Be sure that my grave be not made by a white man; let them not pursue me there!” He died on the 20th of January, 1830, at his residence near Buffalo. With him fell the spirit of his people. They gazed upon his fallen form, and mused upon his prophetic warnings, until their hearts grew heavy with grief. The neighboring missionary, with a disregard for the feelings of the bereaved, and the injunctions of the dead, for which it is difficult to account, assembled his party, took possession of the body, and conveyed it to their meeting-house. The immediate friends of Red Jacket, amazed at the transaction, abandoned the preparation^ they were making for the funeral rites, and followed the body in silence to the place of worship, where a service was performed, which, considering the opinions of the deceased, was as idle as it was indecorous. They were then told, from the sacred desk, that, if they had any thing to say, they had now an opportunity. Incredulity and scorn were pictured on the face of the Indians, and no reply was made except by a chief called Green Blanket, who briefly remarked, ” this house was built for the white man; the friends of Red Jacket cannot be heard in it.” Not with standing this touching appeal, and the dying injunctions of the Seneca chief, his remains were taken to the grave prepared by the whites, and interred. Some of the Indians followed the corpse, but the more immediate friends of Red Jacket took a last view of their lifeless chief, in the sanctuary of that religion which he had always opposed, and hastened from a scene which overwhelmed them with humiliation and sorrow. Thus early did the foot of the white man trample on the dust of the great chief, in accordance with his own prophetic declaration.

The medal which Red Jacket wore, and which is faithfully copied in the portrait before the reader, he prized above all price. It was a personal present, made in 1792, from General Washington. He was never known to be without it. He had studied and comprehended the character of Washington, and placed upon this gift a value corresponding with his exalted opinion of the donor.

See Further: Red Jacket, Seneca War Chief