This article, written in 1890, provides a detailed account of the St. Regis Mohawk people, a group of Indigenous people residing on a reservation that straddles the border of New York and Canada. It examines their history, traditions, and current social, economic, and political realities. The article discusses their unique governance structure, the influence of French culture and Christianity on their way of life, and the challenges posed by their proximity to both the United States and Canada. It also highlights their engagement with the education system and explores the complexities of their identity and naming practices.

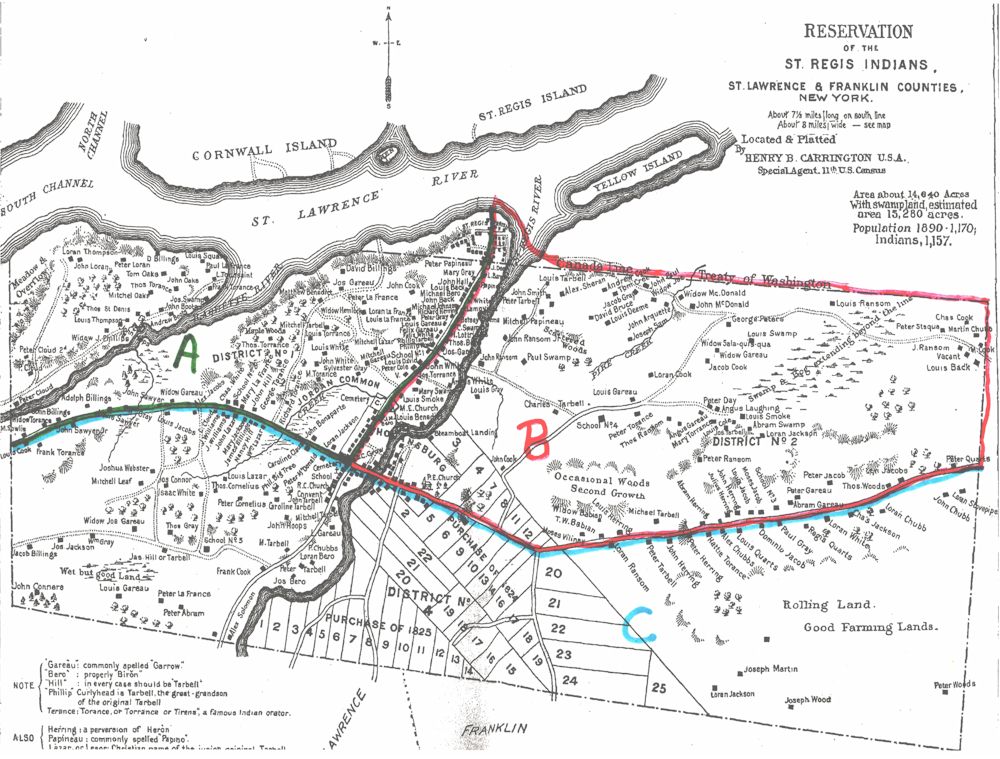

The St. Regis Indians are the successors of the ancient Mohawks and reside on their reservation in Franklin and St. Lawrence counties, New York, which is 7.3 miles long upon the south line and about 3 miles wide, except where purchases made by the state of New York in 1824 and1825, as indicated on the map, found below, modify the shape. The original tract was estimated as the equivalent of 6 miles square, or 23,040 acres, and the acreage in 1890, computed by official reports without survey, is given as 14,640 acres.

Four main roads diverge from the village of Hogansburg, and these are fairly well maintained. Nearly all local roads are poor and little more than trails. The country is practically level, and, in the winter, teams move almost at random anywhere over the snow or ice. In the summer boats are in general use and the products of Indian industry find a ready market. The St. Regis River is navigable to the point indicated on the map and communication is maintained with towns on both sides of the national boundary several times a week. At Messena, 12 miles westward, at Helena, 6 miles southwest, and at Fort Covington, 9 miles eastward, are railroad connections with mail facilities 6 days in the week.

Nearly the entire tract is tillable, and the greater portion has exceptional fertility. The land is slightly rolling, but nowhere hilly. The supply of water is ample, and in portions of the reservation, where swamps or bog prevent tillage, drainage will be necessary before efficient farming can be done. A large tract of this character, containing fully 1,000 acres, extends beyond the boundary line, and complaint has been made by farmers on both sides that the feeder dam of the Beauharnois canal holds back water, so as to reduce even the natural drainage to its minimum. Timber has already become scarce for fuel or fencing, and only occasional clumps of small pines represent the former dense forests along the rivers. The cultivated lands have been quite generally fenced with small poles, but the annual spring repairs only supplement about as much of necessary fencing as is quite generally and conveniently used for fuel during the winter.

The national boundary line established by the treaty of Washington about equally divides the population of the St. Regis Nation. The house, known as the “International hotel”, is bisected diagonally by this boundary line. It also cuts off one of the rooms of the house opposite.

The St. Regis Indians

The St. Regis Indians formed part of the Seven Nations of Canada. In 1852 they numbered 1,100, or nearly the present number of the St. Regis Indians in the United States. By a provision of the first constitution of New York, adopted April 26, 1777, no purchases or contracts for the sale of lands by the Indians since the 14th day of October 1775, were to be valid unless made with the consent of the legislature. Among the documents in the possession of the nation at the present time none are more prized than the treaty made May 4, 1797, exemplified, signed, and sealed by John Jay, governor, February 28, 1800. Three of the most noted parties to that treaty, namely, Te-liar-ag-wan-e-gan (Thomas Williams), A-tia-to-ha-ron-gwam (Colonel Louis Cook), and William Gray, who was made captive in his boyhood and adopted by the Indians, are still represented among the families enumerated upon schedules. Thomas Williams was third in descent from Rev. Thomas Williams, of Deerfield, Massachusetts. Louis Cook was captured with his parents, his father being a colored man, at Saratoga, in 1775. He raised and commanded a regiment on the colonial side. Spark’s Life of Washington and American State Papers are generous in their recognition of the services of Cook and the St. Regis Indians at that period, and the history of the War of 1812 is equally creditable to their loyalty to the United States.

By an act of the legislature passed March 26, 1802, William Gray, Louis Cook, and Loren Tarbell, chiefs, were also appointed trustees on behalf of the St. Regis Indians to lease the ferry over the St. Regis River, with authority to apply the rents and profits for the support of a school and such other purposes as such trustees should judge most conducive to the interests of said tribe. The same act provided for future annual elections of similar trustees by a majority of adults of the age of 21 years, at a town meeting, on the first Tuesday of each May thereafter. This system is still in force.

The powers, functions, and responsibilities of these trustees are hardly more than nominal in practical effect. The peculiar credit, which the Six Nations attach to all preserved treaties, however old or superseded, developed during the census year a new departure in the St. Regis plan of self-government. The old or pagan element among the Onondagas maintained that their rights to lands in Kansas and similar rights rested upon treaties made between the Six Nations (exactly six) and the United States, and at a general council, held in 1888, the St. Regis Indians were formally recognized as the successors of the Mohawks, thus restoring the original five, while, with the Tuscaroras, maintaining six. The theory was that an apparent lapse from the six in number would in some way work to their prejudice. The same element at once proposed the revival of the old government by chiefs, which had become obsolete among the St. Regis Indians. A meeting was held, even among the Cattaraugus Senecas, with the deliberate purpose to ignore or abandon their civilized, legal organization as the Seneca Nation and return to former systems. The impracticability of such a retrograde movement did not silence the advocates of chief ship for the St. Regis Indians. The election through families, after the old method, of 9 chiefs and 9 alternate or vice chiefs was held, and these were duly installed in. office by a general council, representing all the other nations. Practically and legally, they have no power whatever. Two of them are still trustees under the law of 1802.

By tacit understanding the Indians avail themselves of the New York courts in issues of law or fact so far as applicable and submit their conduct to ordinary legal process and civil supervision, so that they have, in fact, no organic institution that antagonizes civilized methods. The distinctions by tribe or clan have almost disappeared, those of the Wolf, Turtle, Bear, and Plover only remaining. Thomas Ramsom, the third trustee, retains in his possession the old treaties and other national archives, while the people, ignorant of the reasons for any change, vibrate between the support of the two systems, neither of which has much real value. The small rentals of land are of little importance in the administration of affairs, and the more intelligent of the prosperous Indians distinctly understand that the elected chiefs have no special authority until recognized by the state of New York as legal successors of the trustees. Either system is that of a consulting, supervising, representative committee of the St. Regis Indians, and little more.

The following is a list of the chiefs in 1890:

Peter Tarbell (Ta-ra-ke-te, Hat-rim, or Neck-protection), great grandson of Peter Tarbell, the eldest of the Groton captives; Joseph Wood (So-se-sa-ro-ne-sa-re-ken, Snow Crust), Heron chin; Peter Herring (Te-ra-non-ra-no-ron-san, Deerhouse), Turtle clan; Alexander Solomon (A-rek-sis-o-ri-hon-ni, He is to Blame), Turtle clan; Angus White, chief and clerk (En-ni-as-ni-ka-un-ta,-a, Small Sticks of Wood), Snipe clan; Charles White (Sa-ro-tha-ne-wa-ne-ken, Two Hide Together), Wolf clan; also Joseph Bero, John White, and Frank Terance, Alternate or vice chiefs are Joseph Cook, Mathew Benedict, Paid Swamp, John B. Tarbell, Philip Wood, and Alexander Jacob (2 vacancies).

There is a pending question among the St, Regis Indians, which may require settlement by both the state and federal governments, respecting their intercourse with their Canadian brethren. Even the census enumeration is affected by its issues. The early treaties, which disregarded the artificial line of separation of these Indians and allowed them free transit over the line with their effects, are confronted by a modern customs regulation, which often works hardships and needless expense. The contingency of their purchasing horses beyond the line and introducing them for personal use, while really intending to sell them at a profit greater than the duty, is not to be ignored; but such cases must be rare, and the peculiarly located families near the line, who worship together, farm together, and live as people do in the adjoining wards of a city, seem to call for a special adjustment to the facts.

Meanwhile the development of the basket industry, and the ready market at Hogansburg, where a single resident firm bought during the year, as their books show, in excess of $20,000 worth, have attracted the Canadian St. Regis Indians across the line, so that the schedules indicate the term of residence of quite a number as less than a year in the United States. Their right to buy land of the St. Regis Indians in New York and erect buildings has been discussed, and the question as to trustees or chiefs as their advisory ruling authority has had this political element as one of the factors. Clerk Angus White furnished a list of those whom he declared to be Canadians proper, drawing Canadian annuities, and on the United States side of the line only to have the benefit of its market for profitable basketwork. The loose holding or tenure of land among the St. Regis Indians makes them jealous of extending privileges beyond the immediate circles, At the same time indispensable daily intimacies prevent the establishment of any arbitrary law of action in the premises. Petitions have been sent to the New York legislature demanding that the Canadians be terribly put across the line. A wise commission could adjust the matter equitably without injustice to any or bad feeling between the adjoining families of the same people. Some who are denounced by one party as Canadians have reared children on the United States side of the line and call it their home. The trustees or chiefs, or both, are continually at work to have stricken from the New York annuity list all whose mixture of white blood on-the female side is decided.

All such questions as those involved in this controversy can only find permanent solution through some ultimate appeal to state or federal authority for distinct and binding settlement.

As a general rule, the state agent is able to adjust the distribution of the state annuity without friction. The St. Regis Indians slowly advance toward a matured citizenship.

St. Regis Reservation Occupants in 1890

We have carefully copied the names listed on the map in hopes it will provide a better record but also help you in your search for ancestors.

Section A – Gree

Loran Thompson

D. Billings

Louis Square

John Loran

Peter Loran

Paul LaFrance

Tom Oaks

John Oaks

Frank Torance

Thos Torance

Mitchel Oaks

Thos St Denis

Jos Swamp

John Boots

Andrew Boots

Louis Thompson

John Hops Widow

J. Phillips

Peter Cloud 2nd

P. Cloud

Peter Cloud

M. Sowlis

Widow Torance

John Billings

Adolph Billings

Louis Sawyer

Wm. Gray

John Sawyer

Widow Gareau

Chas White

School No. 3

Mary LaFrance

John Hill

George Torance

Thomas Torrance

Marthew Benedict

Jos Gareau

David Billings

John Cooketer LaFrance

Widow Hemlock

Louis Torrance

Louis White

John White

Sylvester Gray

M. Torance

Richard Torance

John Bonaparte

Loran Jackson

Cemetery

Peter Cole

Louis David

Mitchell Gareau

Mitchell Lazar

Louis LaFrance

Loran LaFrance

Peter La France

John Cook

School No. 1

Phillip Wood

Phillip Tarbell

Felix White

Felix Gareau

Louis Gareau

Peter Gray

Richard Herring

Michael Johnson

John Back

Michael Bero

Louis Back

John Hall

Mary Gray

Peter Papineau

St. Regis Parish (Part in section)

Section B – Red

S. C. Grow

Hogansburg (town of)

J.M. Bero

M.E. Church

Louis Benedict

Louis Smoke

Mary Swargo

Jos Torrance

John White

Argus White

Louis Gray

Steamboat Landing

P/E. Church

John Ransom

Jos. Gar_all

Thos. Bero

I. Lottrilee

C. Swargo

Betsey Deeme

P. Lamoyiet

M. White

F. Papineau

L. Barro

J.J. Dear

St. Regis Parish (Part in section)

Louis Tarbell

John Smith

Peter Tarbell

Mitchell Papineau

John Ransom Jr.

Paul Swamp

Alex Sheran

Andrew Cook

Tom Cree

Jacob Gray

David Bruce

Louis Deeme

John Arquette

Joseph Sam

John Paul

Widow Joe

Louis Gareau

Loran Cook

Widow McDonald

John McDonald

George Peters

Widow Sala-quis-qua

Widow Gareau

Jacob Cook

Charles Cook

Peter Staqua

Martin Chubb

J. Ransom

M. Cook

Vacant

Louis Back

School No. 4

Peter Torance

Thos Ransom

Angus Gareau

Peter Day

Angus Laughing

Louis Smoke

Mary Torrance

Louis Cole

Jos. Tarbel

Abram Swamp

Loran Jackson

District No. 2

Peter Ransom

Occasional Woods

Widow Babian

T. W. Babian

Moses Vilinay

Louis Herring

Michael Tarbell

Abram Herring

Julius Herring

John Herring

Louis Jacob

Moses Jacob

School No. 3

Peter Jacob

Peter Gareau

Abram Gareau

Thos Woods

Levi Jacobs

Peter Quarts

Section C – Blue

Louis Cook

John Sawyer Jr.

Frank Torance

Louis Sawyer

Wm. Gray

John Sawyer

Louis Jacobs

Joshua Webster

Mitchell Leaf

Widow Jos. Gareau

Jacob Billings

Jos. Jackson

Wm. Gray

John Conners

Louis Gareau

Jas. Hill or Tarbell

Peter LaFrance

Peter Abram

Alex Solomon

Frank Cook

Louis Jacobs

Jos Connor

Isaac White

Thos Gray

L. Cloud

J. Williams

John Lazar

Mary Jackson

James Billings

Nancy Hill

Wm. Lazar

Louis Lazar

Thos. Cornelius

Peter Cornelius

School No. 5

Caroline Clause

Phil Big Tree

Peter McDonald

Cemetery

School

R. C. Church

Convent

John Tarbell

Caroline Trabell

Mitchell Tarbell

John Hoops

L. Gareau

P. Chubbs

Loran Bero

M. Tarbell

Peter Tarbell

Jos Bero

Loran Ransom

Peter Tarbell

John Herring

Peter Herring

Hattie Torance

Alex Chubbs

Louis Quarts

Dominio Jacob

Paul Gray

Regis Quarts

Loran White

Cha’s Jackson

Loran Chubb

John Chubb

Loran Stovepipe

Joseph Martin

Loran Jackson

Joseph Wood

Peter Woods

Religion of the St Regis

Three-fifths of the St. Regis Indians in New York belong to the Roman Catholic church and worship with their Canadian brethren at the parish church of St. Regis, immediately over the Canada line. The church building, which was once partially destroyed by fire, has been restored, and is well lighted and suitably heated. It accommodates about 600 persons, and at one morning service it was crowded with well-dressed, reverent people.

Few churches on American soil are associated with more tradition. One of Mrs. Sigourney’s most exquisite poems, “The Bell of St. Regis,” commemorates the tradition of the transfer of the bell stolen from Deerfield, Massachusetts, February 29, 1774, to the St. Regis tower. The bell went to the church of the Sault St. Louis, at the Caughnawaga village, near Montreal. The three bells at St. Regis came from the Meneely bell shops of Troy within the last 25 years.

The old church records are well preserved, and since the first marriage was solemnized there, February 2, 1763, both marriages and christenings have been recorded with scrupulous care.

The Canadian government withholds from annuities a small sum to maintain the choir and organist by consent of the Canadian Indians, but no organized support flows from the Indians of New York as their proper share.

The Methodist Episcopal church is located just on the margin of the reservation, north from the village of Hogansburg and within the town limits, in order to secure a good title. It is a substantial building, commenced in 1843 and finished in 1845, at a cost of $2,000. The church has 68 communicants, representing one-fourth of the inhabitants of the reservation, and is in a growing, prosperous condition. It is in charge of an earnest preacher, a whole-souled, sympathetic, visiting pastor. The music, the deportment, and the entire conduct of the service, with the loud swelling of nearly 150 voices in the doxology at the close, as well as the occasional spontaneous “amens” and the handshaking before dispersion, left no occasion for doubt that a thorough regenerative work had begun right at the true foundation for all other elevation. Weekly prayer meetings at private houses present another fact that emphasizes the value of the work in progress. The assistant, who is both exhorter and interpreter, and as enthusiastic as his principal, is an Oneida and son of a pious Indian woman, one of the founders of the society. The annual contribution for church expenses is $25. The Methodist Episcopal Missionary Society pays the minister’s salary of $500.

St Regis Traditions

The French element binds the St. Regis Indians closely to the observance of Christian forms and ceremonies, so that legal marriage, baptism of children, and burial of the dead are well-recognized modes of procedure. The social life is informal, and the home life is quite regular, with an air of contented simplicity. All family obligations are well maintained, and the humble homes, the cooperative industry of the children, the rarity of separations, and the number of large households are in harmony.

Among the St. Regis Indians, a marriage custom exists of having three successive suppers or entertainments after the ceremony. The first is at the house of the bride, the second at the house of the bridegroom, and the third at the residence of some convenient friend of both. A procession, bearing utensils, provisions, and all the accessories of a social party, is one of the features. Another custom observed among the St. Regis Indians bears resemblance to the “dead feast” among the pagans of the other nations, namely, that of night entertainments at the house of a deceased person until after the funeral, much like the “wake,” which is almost universal among the white people in the vicinity of Hogansburg, and combines watching the dead body with both social entertainment and religious service.

The predominant thought during the enumeration of this people was that of one immense family, as, indeed, they consider themselves. This sentiment is strengthened by the fact that the invisible boundary which both separates and unites 1,170 New York and 1,180 Canadian St. Regis Indians is practically a bond of sympathy, multiplying the social amenities or visits, and cheering their otherwise lonely and isolated lives. The River Indians also contribute their share in these interchanges of visits.

Education and Schools at St. Regis

There are 5 state schools upon this reservation, under the personal supervision of the state superintendent of these schools. The last school building was erected at a cost of $500, and the aggregate value of the 5 buildings is about $1,400. The salaries of the teachers, all females, are $250 each, and the annual incidental expense of each school is $30. The schools are judiciously located, and the deportment and progress of the pupils are commendable. A new interest has been aroused, as on other reservations, by the various investigations of the conditions and necessities of the Six Nations.

School No. 1, on the St. Regis Road, north from Hogansburg, shows the following record: largest attendance any one day, 31; number attending 1 month or more, 25, namely, 12 males and 13 females, all between the ages of 6 and 18; average age, 10 years; average attendance, 13; largest average attendance any single month, 18, in February. One boy and one girl did not miss a day.

School No. 2 is 8.33 miles from Hogansburg, on the direct road to Fort Covington. Largest attendance any one day, 32; number attending 1 month or more, 28, namely, 12 males and 16 females; under the age of 6, males 2, and females 1; between the ages of 6 and 18, males 11 and females 13; average age, 10 years; average attendance, 13; average attendance any single month, 17, in February. One boy attended every day, and one girl lost but 1 day of the long term.

School No. 3 is nearly 2 miles from Hogansburg, on the direct road west to Messina Springs. Largest attendance any one day, 21; number attending 1 month or more, 24, namely, 11 males and 13 females, all between the ages of 6 and 18; average age, 10 years; average attendance, 15; largest average attendance any single month, 18, in February. One girl lost but 1 day.

School No. 4 is 2.25 miles northeast from Hogansburg, as indicated on the map. Largest attendance any one day, 25; number attending 1 month or more, namely, 13 males and 14 females, all between the ages of 6 and 18; average age, 10 years; average attendance 15; largest average attendance any single month, 18, in February. Three girls and one boy showed exceptional attendance.

School No. 5 is 1.33 miles southwest from Hogansburg, on the new road leading west from the Helena road, at Frank Cook’s. Largest attendance any one day, 21; number attending 1 month or more, 26, namely, 14 males and 12 females, all between the ages of 6 and 18; average age, 10 years; average attendance, 14; largest average attendance any single month, 17, in February; exceptional attendance, 1 girl and 2 boys each lost but one day of the spring term.

The highest aggregate of attendance any single day in the 5 schools was 130. The number of those who attended 1 month or more during the school year of 30 weeks was also 130, or about one-third of the 397 of school age, which in New York ranges from 5 to 21 years. The data given are in accordance with the census schedules.

The qualification as to “reading and writing,” which was made in reporting upon the educational progress of the other nations of the Iroquois league, has even greater force among the St. Regis Indians. One adult read accurately a long newspaper article, upon the promise of half a dollar, but freely acknowledged that he did not understand the subject matter of the article. In penmanship, the faculty of copying or drawing and taking mental pictures of characters as so many objectives become more delusive when the question is asked, “Can you write English?” As for penmanship, most adults who can sign their names do it after a mechanical fashion. The Mohawk dialect of the Iroquois has but 11 letters: A, E, H, I, K, N, O, R, S, T, W. Striking metaphors and figures of speech, which catch the fancy, are in constant use, and to reach the minds of this people similar means must be employed; hence it is that the Methodist minister among the St. Regis Indians proposes that his granddaughter learn their language as the best possible preparation for teaching in English. The objection to Indian teachers is the difficulty of securing those who have thoroughly acquired English. The St. Regis Indians who conduct ordinary conversation in English almost universally hesitate to translate for others when important matters are under consideration, although apparently competent to do so. The white people do not sufficiently insist that Indians who can speak some English should use it habitually. It is so much less trouble to have an interpreter. This people do not, as might be expected, understand French; neither do the Canadian St. Regis Indians. Contact with the Canadian St. Regis Indians, however social and tribal in its affinities and intercourse, retards, rather than quickens, the St. Regis Indians of New York in the acquisition of the English language. It is true with them, as with the other nations, that this is a prime necessity in their upward progress.

Naming Practices Among the St. Regis

Incidental reference has been made to the principal characters who have figured in the history of the St. Regis Indians. Thomas Tarbell (a), the only surviving grandson of the elder captive Tarbell, now at the age of 81, retains a fresh recollection of his childhood and the stories of his grandfather’s experience. He was baptized on the day of his birth, March 2, 1802, as Tio-na-takew-ente, son of Peter Sa-ti-ga-ren-ton, who was the son of Peter Tarbell. One of the family, living on the summit of the Messena road, was known as “Tarbell on the Hill,” giving the name Hill to the next generation. Old Nancy Hill, a pensioner, and 70 years old, thus “lost her real name.” Chief Joseph Wood (b) lost his name through turning the English meaning of his Indian name into a surname. The first Indian who was persuaded to abandon moccasins slept in the boots he had substituted and was afterward only known as “Boots,” his children perpetuating that name. Another, who was surrendered for adoption on consideration of “a quart of rum,” thereby secured to his descendants the name of “Quarts.” Louis Gray, the son of Charles Gray, who figured in the War of 1812, gives the story of his grandfather, William Gray, who was captured at the age of 7 in Massachusetts, and at the age of 19 was permitted to visit his native place, but returned to the Indian who had adopted him, to live and die where Hogansburg is now located. Elias Torrance exhibits the silver medal given to his grandfather by George III, displaying the lion and church, in contrast with a cabin and a wolf, without a hint as to the meaning of the design. Louis Sawyer tells the tale of the early days of St. Regis, learned from his grandmother, Old Ann, who died at the age of 101. Louis has 3 sons in Minnesota, and a French wife, so that he has much trouble about the time of the annuity payment. He is a Methodist, can read and write, and thinks he pays a penalty for these distinctions.

The St. Regis Indians have a strangely mixed ancestry of French influences, white captives, and 1 colored man, with well-preserved traditions of all, but with few memorials of their purely Indian history. One wampum, now owned by Margaret Cook, the aged aunt of Running Deer, represents the treaty of George I with the Seven Nations. The king and head chief are represented with joined hands, while on each side is a dog, watchful of danger, and the emblem is supposed to be the pledge: “We will live together or die together. We promise this as long as water runs, the skies do shine, and the night brings rest.” Hough describes Tirens, one of the sources of the name Torrance, as an Oswegatchie Indian, known as “Peter the Big Speak,” because of his bold oratory, as a son of Lesor Tarbell, the younger of the captive brothers. Here again, the confusion of names finds its result in the various names culminating in the surname Lazar.

The surroundings of St. Regis are named with singular fitness to their properties, and yet these, as elsewhere, have gradually lost their title in order to honor some ambitious white man, whose life is crowned with glory if the word “ville” or “burg” can be joined to his name, sacrificing that which the Natives so happily fitted to its place.

See Further

1896 St. Regis Indians Census

Census of the St. Regis Tribe of Indians of New York Agency, New York taken by Alexander Solomon, Chief, for J. R. Jewell, United States Indian Agent June 1896.

St. Regis Colony

This passage is a historical account of the St. Regis Colony, a community of Iroquois people who converted to Catholicism in the 17th and 18th centuries. The author traces the origins of the colony to French missionary efforts and the political maneuvering of the French monarchy, which sought to expand its influence in North America at the expense of the British. The St. Regis community, composed primarily of Mohawks, was seen as a strategic asset by the French and was encouraged to separate from the main Iroquois Confederacy. This separation led to tensions and resentment between the St. Regis community and the other Iroquois tribes, who viewed them as outsiders and collaborators with the French. The author highlights the role of the St. Regis Colony in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, emphasizing its actions as a source of conflict and suffering for frontier settlements. Finally, the passage concludes by describing the St. Regis population and its division between Canada and the United States as a result of the Treaty of Ghent.

Gallery of Men in 1890