To a description of this last people, now, as a separate race, entirely extinct, Mr. Catlin has devoted no small portion of his interesting descriptions of western adventure. They differed widely from all other American Indians in several particulars. The most noticeable of these were the great diversity in complexion and in the color and texture of the hair. “When visited by this traveler, in 1832, the Mandan were established at two villages, only two miles asunder, upon the left bank of the Missouri, about two hundred miles below the mouth of the Yellowstone.

There were then not far from two thousand of the tribe, but, from their own traditions, and from the extensive ruins of their former settlement some distance below it was evident that their numbers had greatly decreased. The principal town was strongly fortified upon the precipitous riverbank, on two sides defended by the winding stream, and on the other by picketing of heavy timber, and by a ditch. The houses within were so closely set as to allow of little space for locomotion. They were partially sunk in the ground, and the roofs were covered with earth and clay to such a depth and of such consistency that they afforded the favorite lounging places for the occupants.

“One is surprised,” says Catlin, “when he enters them, to see the neatness, comfort, and spacious dimensions of these earth-covered dwellings. They all have a circular form, and are from forty to sixty feet in diameter. Their foundations are prepared by digging some two feet in the ground, and forming the floor of earth, by leveling the requisite size for the lodge.” The building consisted of a row of perpendicular stakes or timbers, six feet or there about in height, supporting long rafters for the roof. A hole was left in the center for air, light, and the escape of smoke. The rafters were supported in the middle by beams and posts: over them was laid a thick coating of willow brush, and over all the covering of earth and clay. An excavation in the center of the hut was used as a fireplace. Each of these houses served for a single family, or for a whole circle of connections, according to its dimensions. The furniture consisted of little more than a rude sort of bedsteads, with sacking of buffalo skin, and some times an ornamental curtain of the same material. Posts were set in the ground, between the beds, provided with pegs, from which depended the arms and accoutrements of the warriors.

“This arrangement of beds, of arms, &c.,” continues our author, “combining the most vivid display and arrangement of colors, of furs, of trinkets of barbed and glistening points and steel of mysteries and hocus pocus, together with the somber and smoked color of the roof and sides of the lodge; and the wild, and rude, and red the graceful (though uncivil) conversational, garrulous, story-telling, and happy, though ignorant and untutored groups, that are smoking their pipes wooing their sweet hearts, and embracing their little ones about their peaceful and endeared firesides; together with their pots and kettles, spoons, and other culinary articles of their own manufacture, around them; present, altogether, one of the most picturesque scenes to the eye of a stranger that can be possibly seen; and far more wild and vivid than could ever be imagined.”

If the sight within the dwellings was novel and striking, much more so was that which occupied the painter’s attention as he surveyed, from the roof of one of these domes, the motley scene of busy life without. In the center of the village an open court was left for purposes of recreation and for the performances of the national religious ceremonies. Upon the rounded roofs of the domiciles numerous busy or indolent groups were sitting or lounging in every possible attitude, while in the central area some were exercising their wild horses, or training and playing with their dogs. Such a variety of brilliant and fanciful costume, ornamented with plumes and porcupine quills, with the picturesque throng of Indians and animals, the closely crowded village, the green plain, the river, and the blue hills in the distance, formed a happy subject for the artist.

Their Cemeteries, Affectionate Remembrance of the Dead

Without the picket of defense, the only objects visible, of man’s construction, were the scaffolding upon which the dead were exposed. The manner in which the funeral rites of the Mandan were conducted, with the subsequent details, constitutes the most touching portion of the author’s narrative. The body of the dead person was tightly wrapped and bound up in fresh or soaked buffalo skins, together with the arms and accoutrements used in life, and the usual provision of tobacco, flint and steel, knife, and food. A slight scaffold is then prepared, of sufficient height to serve as protection from the wolves and dogs, and there the body is deposited to decay in the open air.

Day after day those who had lost friends would come out from the village to this strange cemetery, to weep and bewail over their loss. Such genuine and long-continued grief as was exhibited by the afflicted relatives puts to shame the cold heartedness of too many among the cultivated and enlightened. When, after the lapse of years, the scaffolds had fallen, and nothing was left but bleached and moldering bones, the remains were buried, with the exception of the skulls. These were placed in circles upon the plain, with the faces turned inward, each resting upon a bunch of wild sage; and in the center, upon two slight mounds, “medicine-poles” were erected, at the foot of which were the heads and horns of a male and a female buffalo. To these new places of deposit, each of which contained not far from one hundred skulls, “do these people,” says Catlin, “again resort, to evince their further affection for the dead not in groans and lamentations, however, for several years have cured the anguish but fond affections and endearments are here renewed, and conversations are here held, and cherished, with the dead.”

The wife or mother would sit for hours by the side of the white relic of the loved and lost, addressing the skull with the most affectionate and loving tones, or, perchance lying down and falling asleep with her arms around it. Food would be nightly set before many of these “skulls, and, with the most tender care, the aromatic bed upon which they reposed would be renewed as it withered and decayed.

Personal Appearance and Peculiarities of the Mandan

Unlike the other Indian tribes of the west, the Mandan, instead of presenting a perfect uniformity in complexion, and in the color of the eyes and hair, exhibited as great diversity in these respects as will be noticed in a mixed population of Europeans. Their hair was, for the most part, very fine and soft, but in a number of in stances a strange anomaly was observable, both in old and young, and in either sex, viz.: a profusion of coarse locks of “a bright silvery gray,” approaching sometimes to white.

Some of the women were quite fair, with blue eyes, and the most symmetrical features, combined with a very attractive and agreeable expression. It does not appear probable that sufficient inter-mixture with European races had ever taken place to account for these peculiarities, and some authors appear quite convinced that these Mandan are the remains of a great people, entirely distinct from the nations around them. Of Mr. Catlin’s researches and conclusions respecting their origin, we shall take occasion to speak hereafter.

Their Hospitality And Urbanity

In their disposition the Mandan were hospitable and friendly; affectionate and kind in their treatment of each other; and mindful of the convenience and comfort of the stranger. Their figures were beautifully proportioned, and their movements and attitudes graceful and easy. Instead of the closely shorn locks of some other races, they wore their hair long. The men were particularly proud of this appendage, and were at no small pains to arrange it in what they esteemed a becoming manner. It was thrown backward from the forehead, and divided into a number of plaits. These were kept in their position by glue and some red-tinted earth, with which they were matted at intervals. The women oiled and braided their hair, parting it in the middle; the place of parting was universally painted red.

Their Cleanliness Of Person

A greater degree of cleanliness was observable in their persons than is common among savages. A particular location was assigned, at some distance from the village, up the river, where the women could resort undisturbed for their morning ablutions. A guard was stationed, at intervals, upon a surrounding circle of rising ground, to prevent intrusion. Those of both sexes and all ages were excellent swimmers; scarcely was one to be found who could not with ease cross the Missouri in. this manner. Their only boats were round tubs made by stretching buffalo-skins over a light framework. The form and capacity of these clumsy watercraft, were strikingly similar to that of the coracles used in Wales and upon other portions of the coast of Great Britain.

As an additional means of luxury, and as an efficient remedy in case of sickness, a hut was devoted to the purpose of a steam bath. This was effected by pouring upon heated stones, over which the patient was placed, wrapped in buffalo robes, in a wicker-basket. The operation was always followed up by a plunge into the river, and a subsequent rubbing and oiling of the body. Such a mode of treatment produced terrible effects, in after times, when the small-pox spread through the tribe.

The dress of the Mandan warriors, although in its general fashion similar to that of the neighboring tribes, was singularly rich and elaborate. It was formed entirely of skins: a coat or hunting-shirt of buckskin; leggins and moccasins of the same material, beautifully fringed, and embroidered with porcupine quills; and an outer mantle of the fur of a young buffalo, formed the principal equipment. The covering for the head was more elaborate, and was constructed, by all who could obtain the materials, of ermine skins, and feathers of the war-eagle. So high a value was set upon these head-dresses, that Mr. Catlin, after having bargained for the entire suit of a chief, whose portrait he had just painted, was obliged to give two horses, of the value of twenty-five dollars each, for the crowning ornament. Some few chiefs had attained a height of authority and renown, which entitled them to add to their headdress a pair of buffalo-horns, reduced in size and weight, and arranged as they grew upon the animal. The custom was not confined to the Mandan, but a similar ornament is widely considered as symbolic of power and warlike achievements among the western Indians.

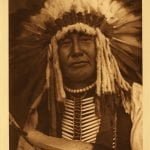

Portraits Of Mandan Chiefs

Nothing could exceed the pride and delight of the chiefs of the tribe, after their first apprehensions at the novelty of the proceeding were allayed, at the sight of their own portraits, for which they were induced to sit by our author. He was constituted and proclaimed from the moment of the first exhibition, a “great medicine-man,” and old and young thronged to see and to touch the worker of such a miracle. All declared that the pictures were, at least partially, alive: for from whatsoever side they were beheld, still the eyes were seen fixed upon the beholder. An idea was started, and obtained a temporary credence, that some portion of the life of the person represented must have been abstracted by the painter, and that consequently his term of existence must be shortened. It was moreover feared, lest, by the picture s living after the death of the original, the quiet rest of the grave should be troubled.

By a most ingenious and judicious policy in adopting a mode of explanation suited to the capacity of his hearers, and by wisely ingratiating himself with the chiefs and medicine men, Mr. Catlin succeeded in stilling the commotion excited by such suggestions and suspicions. He was held in high estimation, and feasted by the principal men of the tribe, whose portraits he obtained for his invaluable collection.

Contrast Between The Wild Tribes And Those Of The Frontier

It is only among such remote tribes as the one which forms the subject of our present consideration, that any adequate idea can be formed of the true Indian character. The gluttony, drunkenness, surliness, and “shiftlessness” of the degraded race, that has caught the vices of the white man, without aiming at his civilization, are strongly contrasted with the abstemiousness, self-respect, and native dignity of the uncontaminated. ” Amongst the wild Indians in this country,” says Catlin, “there are no beggars no drunkards and every man, from a beautiful natural precept, studies to keep his body and mind in such a healthy shape and condition as will at all times enable him to use his weapons in self defense, or struggle for the prize in their manly games.”

The usual custom of polygamy was universally practiced among the Mandan, by all whose rank, position and means enabled them to make the necessary arrangements, and pay the stipulated price for their wives. The girls were generally sold by their parents at a very early age, and, as among most barbarous nations, their fate was a life of toil and drudgery. Their time must be almost constantly employed in getting fuel, cultivating com and squashes, preparing pemmican and other dried stores for winter, and in dressing and embroidering the buffalo-robes which their lord and master accumulated for trade with the whites.

Notwithstanding this apparently degraded position, we are informed that the women were seemingly contented with their lot, that they were modest in their deportment, and that ” amongst the respectable families, virtue” was “as highly cherished, and as inapproachable as in any society whatever.”

White traders among the extreme western tribes are said to be almost universally in the custom, from motives of policy, and perhaps from inclination, of allying them selves to one, at least, of the principal chiefs, by a temporary espousal of his daughter. In many instances they indulge in a plurality. This is a position greatly sought after by the young women, as they are enabled by it to indulge their native fondness for display, and are freed from the toil usually incident to their existence.

The men and boys, leading a life of ease, except when engaged upon a hunt, practiced a great variety of games and athletic sports, some of them very curious and original. Horse-racing, ball-playing, archery, &c., never failed to excite and delight them. An endless variety of dances, with vocal and instrumental accompaniments, served for recreation and religious ceremonials. Every word and step had some particular and occult signification, for the most part known only to those initiated in the mysteries of ” medicine.”

In times of scarcity, when the buffalo herds had wandered away from the vicinity, so far that the hunters dared not pursue them, for fear of enemies, the “buffalo dance” was performed in the central court of the village. Every man of the tribe possessed a mask made from the skin of a buffalo s head, including the horns, and dried as nearly as possible in the natural shape, to be worn on these occasions. When the wise men of the nation determined upon their invocations to attract the buffalo herds, watchers were stationed upon the eminences surrounding the village, and the dance commenced. With extravagant action, and strange ejaculations, the crowd performed the prescribed maneuvers: as fast as those engaged became weary, they would signify it by crouching down, when those without the circle would go through the pantomime of severally shooting, flaying, and dressing them, while new performers took their place. Night and day the mad scene was kept up, sometimes for weeks together! until the signal was given of the approach of buffalo, when all prepared with joy and hilarity for a grand hunt, fully convinced that their own exertions had secured the prize.

No less singular was the ceremonial resorted to when the crops were suffering for want of rain. A knot of the wisest medicine- men would collect in a hut, where they held their session with closed doors, burning aromatic herbs and going through with an unknown series of incantations. Some tyro was then sent up to take his stand 011 the roof, in sight of the people, and spend the day in invocations for a shower. If the sky continued clear, he retired in disgrace, as one who need not hope ever to arrive at the dignity of a medicine-man. Day after day the performance continued, until a cloud overspread the skies, when the young Indian on the lodge discharged an arrow towards it, to let out the rain. From their earliest youth, the boys were trained to the mimic exercises of war and the chase. It was a beautiful sight to witness the spirit with which they would enact a sham fight upon the open prairie. A tuft of grass supplied the place of the scalp lock, and blunt arrows of grass or reeds, with wooden scalping-knives, formed their innocuous weapons. “If any one,” says Catlin, “is struck with an arrow on any vital part of his body, he is obliged to fall, and his adversary rushes up to him, places his foot upon him, and snatching from his belt his wooden knife, grasps hold of his victim s scalp-lock of grass, and making a feint at it with his wooden knife, snatches it off and puts it into his belt, and enters again into the ranks and front of battle.”

This was the true mode of forming warriors. The youth grew to manhood with the one idea that true dignity and glory awaited him alone who could fringe his garments with the scalps of his enemies. Some of the Mandan braves, even of their last generation, performed feats of daring, and engaged in chivalrous combats, which will almost compare with the deeds of Piskaret or Hiadeoni in the early history of the Iroquois.

The Great Annual Religious Ceremony

At the risk of seeming to linger too long over the history and customs of a single tribe, few in numbers, and now extinct, we will give some description of the strange religious ceremony which occupied four days of each returning year. The religious belief of the Mandan was, in the main, not unlike that of most North American aborigines; but some of their self-torturing modes of adoration and propitiation of their deity were perfectly unique. The grand four days ceremony had, according to Catlin, three distinct objects; a festival of thanksgiving for the escape of their ancestors from the flood! of which they had a distinct tradition, strikingly conformable to scriptural history; for the grand ” bull-dance,” to draw the buffalo herds towards the settlement; and to initiate the young men, by terrible trials and tortures, into the order of warriors, and to allow those whose fortitude had been fully tested to give renewed proofs of their capacity of endurance, and their claim to the position of chiefs and leaders.

The period for the ceremony was that in which the leaves of the willow on the river bank were first fully opened; “for, according to their tradition says Catlin, “the twig that the bird brought home was a willow bough, and had full-grown leaves upon it, and the bird to which they allude is the mourning or turtle-dove, which they took great pains to point out to me,” as a medicine-bird. The first performances bore reference to the deluge, in commemoration of which a sort of “curb or hogshead” stood in the center of the village court, symbolical of the “big canoe,” in which the human race was preserved.

No intimation was given by the wise men, under whose secret management the whole affair was conducted, of the precise day when the grand celebration should commence; but at sunrise, one morning, Mr. Catlin and his white companions were aroused by a terrible tumult throughout the village. All seemed to be in a state of the greatest excitement and alarm, the cause of which was unexplainable, as the object at which all were gazing was a single figure, approaching the village, from a bluff, about a mile distant. This personage soon entered within the enclosed space of the town: he was painted with white clay, and carried a large pipe in his hand. He was saluted by the principal men of the tribe as “Nu-mohk-muck-a-nah, (the first or only man,” in fact, none other than Noah himself,) who had come to open the great lodge reserved exclusively for the annual religious rites.

Having superintended the preparation of the medicine-house, and leaving men busy in adorning it with willow boughs and sage, and in the arrangement of divers skulls, both of men and buffaloes, which were essential in the coming mysteries, Nu-mohk-muck-a-nah made the rounds of the village, repeating before every lodge the tale of the great deluge, and telling how he alone had been saved in his ark, and left by the retiring waters upon the summit of a western mountain!

At every hut he was presented with some cutting instrument, (such as was supposed to have been used in the construction of the ark,) to be thrown into the river as a sacrifice to the waters.

Next day, having ushered the young men who were to go through the fearful ordeal of self-inflicted torture into the sacred lodge, and appointed an old medicine-man to the office of “O-kee-pah Ka-se-kah, (keeper or conductor of the ceremonies,”) he took up his march into the prairie, promising to appear again on the return of the season in the ensuing year.

The young warriors, preparatory to undergoing the torture, were obliged, until the fourth day from their entry into the lodge, to abstain from food, drink, or sleep! Meanwhile, various strange scenes were enacted in the central area before the house. The grand buffalo-dance, a performance combining every thing conceivable of the grotesque and extravagant, was solemnly performed to in sure a favorable season for the chase.

On the fourth day commenced the more horrible portion of the exercises. Mr. Catlin, as a great medicine man, was admitted within the lodge throughout the performances, and had full opportunity to portray, with pen and pencil, the scenes therein enacted. Coming forward, in turn, the victims allowed the flesh of their breasts or backs to be pierced with a rough two-edged knife, and splinters of wood to be thrust through the holes. Enough of the skin and flesh were taken up to be more than sufficient for the support of the weight of the body. To these splints cords let down from the roof were attached, and the subject of these inflictions was hoisted from the ground. Similar splints were then thrust through the arms and legs, to which the warrior s arms, and, in some cases, as additional weights, several heavy buffalo heads, were hung.

Thus far the fortitude of the Indian sufficed to restrain all exhibition of pain; while the flesh was torn with the rude knife, and the wooden skewers were thrust in, a pleasant smile was frequently observable on the young warrior s countenance; but when in the horrible position above described, with his flesh stretched by the splints till it appeared about to give way, a number of attendants commenced turning him round and round with poles, he would “burst out in the most lamentable and heart-rending cries that the human voice is capable of producing, crying forth to the Great Spirit to support and protect him in this dreadful trial.”

After hanging until total insensibility brought a temporary relief to his sufferings, he was lowered to the floor, the main supporting skewers were withdrawn, and he was left to crawl off, dragging the weights after him. The first movement, with returning consciousness, was to sacrifice to the Great Spirit one or more of the fingers of the left hand, after which the miserable wretch was taken out of the lodge. Within the court a new trial awaited him; the last, but most terrible of all. An active man took his position on each side of the weak and mutilated sufferer, and, passing a thong about his wrist, urged him forward at the top of his speed in a circle round the arena. When, faint and weary, he sank on the ground, the tormentors dragged him furiously around the ring until the splints were torn out by the weights attached, and he lay motionless and apparently lifeless. If the splint should have been so deeply inserted that no force even that of the weight of individuals in the crowd, thrown upon the trailing skulls could break the integuments, nothing remained but to crawl off to the prairie, and wait until it should give way by suppuration. To draw the skewer out would be unpardonable sacrilege.

It is told of one man that he suspended himself from the precipitous riverbank by two of these skewers, thrust through his arms, until, at the end of several days! he dropped into the water, and swam ashore. Throughout the whole ordeal, the chiefs and sages of the tribe critically observed the comparative fortitude and endurance of the candidates, and formed their conclusions thereupon, as to which would be the worthiest to command in after time.

With all these frightful and hideous sights before his eyes, or fresh in his recollection, our author still maintains, and apparently upon good grounds, and in honest sincerity, his former eulogium upon the virtues and natural, noble endowments of these singular people. We have given, above, but a brief outline of the mysterious conjurations attendant upon the great annual festival: many of these lack interest from our ignorance of their signification.

The Mandan Supposed To Be Of Welsh Descent

A favorite theme for theorists, ever since the early ages of American colonization, has been found in the endeavor to trace a descent from the followers of the Welsh voyager, Prince Madoc, to sundry Indian tribes of the west. Vague accounts of Indians of light complexion, who could speak and understand the Welsh language, are given by various early writers. They were generally located by the narrator in some indeterminate region west of the Mississippi, at a considerable distance above New Orleans, but no where near the Missouri.

It is to be regretted that these ancient accounts are so loose and uncertain, as there can be no doubt but that they are founded upon striking and important facts. A list of Mandan words, compared with Welsh of the same signification, has been made public by Mr. Catlin, in which the resemblance is so clear, that almost any theory would be more credible than that such affinity was accidental. This author traced remains of the peculiar villages of the Mandan nearly to the mouth of the Missouri, and describes others of similar character to the northward of Cincinnati.

He supposes that the adventurers, who sailed from Wales in the year 1170, and were never thenceforth heard from, after landing at Florida, or near the mouth of the Mississippi, made their way to Ohio; that they there became involved in hostilities with the natives, and were eventually all cut off with the exception of the half-breeds, who had sprung up from connection with the women of the country; that these half-breeds had at one time formed a powerful tribe, but had gradually been reduced to those whom we have described, and had removed or been driven farther and farther up the Missouri. The arguments upon which this hypothesis is based are drawn from a careful examination of ancient western fortifications; from physical peculiarities, and the analogies in language above referred to; from certain arts of working in pottery, &c.; and from the remarkable and isolated position occupied by the tribe in question among hostile nations of indubitable aboriginal characteristics. The theory is, to say the least, plausible, and ably supported.

Annihilation Of The Tribe By The Small-Pox

In the summer of 1838, the small-pox was communicated to the Mandan from some infected persons on board one of the steamers belonging to a company of fur-traders. So virulent was the disease, that in a few weeks it swept off the whole tribe, except a few who fell into the hands of their enemies, the Ricarees. One principal reason for the excessive mortality is said to have been, that hostile bands of Indians had beset the village, and the inhabitants were consequently unable to separate, or to place the infected in an isolated position.

The scene of death, lamentation, and terror is said by those who witnessed it to have been frightful in the extreme. Great numbers perished by leaping into the river, in the paroxysm of fever, being too weak to swim out.

Those who died in the village lay in heaps upon the floors of the huts. Of the few secured by the Ricarees who took possession of the depopulated village, nearly all were said to have been killed during some subsequent hostilities, so that now scarce a vestige of the tribe can be supposed to remain.

The Mandan were probably all congregated at their principal village at the time of the great calamity: the other village was situated two miles below, was a small settlement, and was used, as we are led to infer, merely for a temporary “summer residence for a few of the noted families.”

Mr. Catlin adds the following items to his account of the annihilation of this interesting tribe: “There is yet a melancholy part of the tale to be told, relating to the ravages of this frightful disease in that country on the same occasion, as it spread to other contiguous tribes, the Minatarree, the Knisteneaux, the Blackfeet, the Chayenne, and the Crows, amongst whom twenty-five thousand perished in the course of four or five months, which most appalling facts I got from Major Pilcher, superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis, from Mr. McKenzie, and others.”