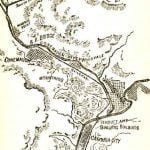

At this point of our narrative a sketch of Johnstown, where the most frightful havoc of the flood occurred, will interest the reader.

At this point of our narrative a sketch of Johnstown, where the most frightful havoc of the flood occurred, will interest the reader.

The following description and history of the Cambria Iron Company’s Works, at Johnstown, is taken from a report prepared by the State Bureau of Industrial Statistics:

The great works operated by the Cambria Iron Company originated in a few widely separated charcoal furnaces, which were built by pioneer iron workers in the early years of this century. It was chartered under the general law authorizing the incorporation of iron manufacturing companies, in the year 1852. The purpose was to operate four old-fashioned charcoal furnaces, located in and about Johnstown, some of which had been erected many years before. Johnstown was then a village of 1300 inhabitants. The Pennsylvania Railroad had only been extended thus far in 1852, and the early iron manufacturers rightly foresaw a great future for the industry at this point.

Immense Furnaces

Coal, iron and limestone were abundant, and the new railroad would enable them to find ready markets for their products. In 1853 the construction of four coke furnaces was commenced, and it was two years before the first was completed, while some progress was made on the other three. England was then shipping rails into this country under a low duty, and the iron industry, then in its infancy, was struggling for existence.

The furnaces at Johnstown labored under greater difficulties in the years between 1852 and 1861 than can be appreciated at this late day. Had it not been for a few patriotic citizens in Philadelphia, who loaned their credit and means to the failing company, the city of Johnstown would possibly never have been built. Notwithstanding the protecting care of the Philadelphia merchants, the company in Johnstown was unable to continue in business, and suspended in 1854. Among its heaviest creditors in Philadelphia were Oliver Martin and Martin, Morrell & Co. More money was subscribed, but the establishment failed again in 1855. D. J. Morrell, however, formed a new company with new credit.

Recovery From a Great Fire

The year of 1856, the first after the lease was made, was one of great financial depression, and the following year was worse. To render the situation still more gloomy a fire broke out in June, 1857, and in three hours the large mill was a mass of ruins. Men stood in double ranks passing water from the Conemaugh river, 300 yards distant, with which to fight the flames. So great was the energy, determination and financial ability of the new company that in one week after the fire the furnaces and rolls were once more in operation under a temporary structure. At this early stage in the manufacturing the management found it advisable to abandon the original and widely separated charcoal furnaces and depend on newly constructed coke furnaces. As soon as practicable after the fire a permanent brick mill was erected, and the company was once more fully equipped. When the war came and with it the Morrill tariff of 1861 a broader field was opened up. Industry and activity in business became general; new life was infused into every enterprise. In 1862 the lease by which the company had been successfully operated for seven years expired, and by a reorganization the present company was formed.

Advent of Steel Rails

A new era in the manufacture of iron and steel was now about to dawn upon the American people. In this year 1870 there were 49,757 tons of steel produced in the United States, while in 1880 the production was 1,058,314 tons. Open hearth steel, crucible steel and blister steel, prior to this, had been the principal products, but were manufactured by processes too slow and too expensive to take the place of iron. The durability of steel over iron, particularly for rails, had long been known, but its cost of production prevented its use. In 1857 one steel rail was sent to Derby, England, and laid down on the Midland Railroad, at a place where the travel was so great that iron rails then in use had to be renewed sometimes as often as once in three months. In June, 1873, after sixteen years of use, the rail, being well worn, was taken out. During its time 1,250,000 trains, not to speak of the detached engines, etc., had passed over it. This was the first steel rail, now called Bessemer rail, ever used.

About ten years ago the Cambria Iron Company arranged with Dr. J.H. Gautier & Sons, of Jersey City, to organize a limited partnership association under the name of “The Gautier Steel Company, Limited,” to manufacture, at Johnstown, wire and various other forms of merchant steel. Within less than a mile from the main works extensive mills were erected and the business soon grew to great proportions. In a few years so much additional capital was required, owing to the rapidly increasing business, that Dr. Gautier, then far advanced in life, wished to be relieved of the cares and duties incident to the growing trade, and the Cambria Iron Company became the purchaser of his works. “The Gautier Steel Company, Limited,” went out of existence and the works are now known as the “Gautier Steel Department of Cambria Iron Company.”

Description of the Works

The blast furnaces, steel works and rolling mills of the company are situated upon what was originally a river flat, where the valley of the Conemaugh expanded somewhat just below the borough of Johnstown, and now forming part of Millville Borough. The arrangement of the works has been necessarily governed by the fact that they have gradually expanded from the original rolling-mill and four old style blast furnaces to their present character and capacity of which some idea may be obtained by the condensed description given below.

The Johnstown furnaces, Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4, form one complete plant, with stacks seventy-five feet high, sixteen feet diameter of bosh. Steam is generated in forty boilers, fired by furnace gas, for eight vertical direct-acting blowing engines. Nos. 5 and 6 blast furnaces form together a second plant with stacks seventy-five feet high, nineteen feet diameter of bosh. No. 5 has iron hot blast stoves and No. 6 has four Whitwell fire-brick hot blast stoves. The furnaces have together six blowing engines exactly like those at Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4 furnaces. The engines are supplied with steam by thirty-two cylinder boilers.

Marvelous Machinery

The Bessemer plant was the sixth started in the United States (July, 1871). The main building is 102 feet in width by 165 feet in length. The cupolas are six in number. Blast is supplied from eight Baker rotary pressure blowers driven by engines sixteen inches by twenty-four inches, at 110 revolutions per minute. The cupolas are located on either side of the main trough, into which they are tapped, and down which the melted metal is directed into a ten-ton ladle set on a hydraulic weighing platform, where it is stored until the converters are ready to receive it. There are two vessels of eight and a half tons capacity each, the products being distributed by a hydraulic ladle crane. The vessels are blown by three engines. The Bessemer works are supplied with steam by a battery of twenty-one tubular boilers.

The best average, although not the very highest work done in the Bessemer department is 103 heats of eight and a half tons each for twenty-four hours. The best weekly record reached 1,847 tons of ingots, the best monthly record of 20,304 tons, and the best daily output, 900 tons ingots. All grades of steel are made in the converters from the softest wire and bridge stock to spring steel. All the special stock, that is other than rails, is carefully analyzed by heats, and the physical properties are determined by a tension test.

Ponderous Steam-Hammers

The open hearth building, 120 feet in width by 155 feet in length, contains three Pernot revolving hearth furnaces of fifteen tons capacity each, supplied with natural gas. A separate pit with a hydraulic ladle crane of twenty tons capacity is located in front of each pan. In a portion of the mill building, originally used as a puddle mill, is located the bolt and nut works, wherein are made track bolts and machine bolts. This department is equipped with bolt-heading and nut making machines, cutting, tapping and facing machines, and produces about one thousand kegs of finished track bolts, of 200 pounds each, per month, besides machine bolts. Near this, also, are located the axle and forging shops, in the old puddle mill building. The axle shop has three steam hammers to forge and ten machines to cut off, centre and turn axles. The capacity of this shop is 100 finished steel axles per day. All axles are toughened and annealed by a patented process, giving the strongest axle possible. In the forging plant, located in the same building, there is an 18,000 pound Bement hammer, and a ten-ton traveling crane to convey forgings from the furnaces to the hammer. There are two furnaces for heating large ingots and blooms for forgings.

A ventilating fan supplies fresh air to the mills through pipes located overhead, and having outlets near the heating furnaces. One hundred thousand cubic feet of fresh air per minute is distributed throughout the mills. The mill has in addition to its boilers, over the heating-furnaces, a brick and iron building, located near the rail mill, 205 feet long and 45 feet wide, containing twenty-four tubular boilers, aggregating about 2000 horse-power.

Tons of Barbed Wire

The “Gautier Steel Department” consists of a brick building 200 feet by 500 feet, where the wire is annealed, drawn and finished; a brick warehouse 373 feet by 43 feet; many shops, offices, etc.; the barb wire mill, 50 feet by 256 feet, where the celebrated Cambria Link barb wire is made; and the main merchant mill, 725 feet by 250 feet. These mills produce wire, shafting, springs, plowshare, rake and harrow teeth and other kinds of agricultural implement steel. In 1887 they produced 50,000 tons of this material, which was marketed mainly in the Western states.

Grouped with the principal mills are the foundries, pattern and other shops, drafting offices, time offices, etc., all structures being of a firm and substantial character. The company operates about thirty-five miles of railroad tracks, employing in this service twenty-four locomotives, and it owns 1500 cars.

In the fall of 1886 natural gas was introduced into the works.

Building up Johnstown

Anxious to secure employment for the daughters and widows of the employees of the company who were willing to work, its management erected a woolen mill which now employs about 300 persons. Amusements were not neglected, and the people of Johnstown are indebted to the company for the erection of an opera house, where dramatic entertainments are given.

The company owns 700 houses, which are rented exclusively to employees. The handsome library erected by the company and presented to the town was stocked with nearly 7000 volumes. The Cambria Hospital is also under the control of the beneficial association of the works. The Cambria Clubhouse is a very neat pressed brick building on the corner of Main and Federal streets. It was first operated in 1881, and is used exclusively for the entertainment of the guests of the company and such of their employees as can be accommodated. The store building occupied by Wood, Morrell & Co., limited, is a four-story brick structure on Washington street, with three large store rooms on the first floor, the remainder of the building being used for various forms of merchandise.

Including the surrounding boroughs, Kernville, Morrellville and Cambria City, all of which are built up solidly to Johnstown proper, the population is about 30,000. The Cambria Iron Company employs, in Johnstown, about 7500 people, which would certainly indicate a population of not less than 20,000 depending upon the company for a livelihood.

A large proportion of the population of Johnstown are citizens of foreign birth, or their immediate descendants. Those of German, Irish, Welsh and English birth or extraction predominate, with a few Swedes and Frenchmen. As a rule the working people and their families are well dressed and orderly; in this they are above the average. Most of the older workmen of the company, owing largely to its liberal policy, own their houses, and many of them have houses for rent.