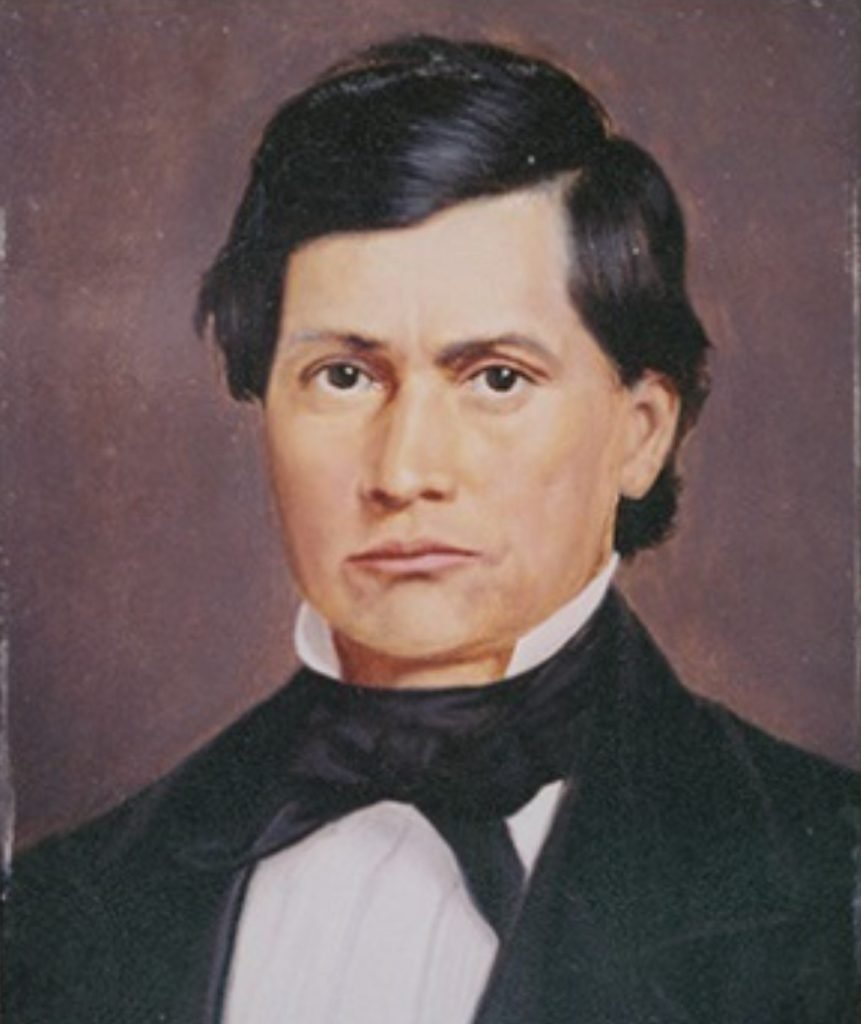

Cyrus Harris, a significant figure in the history of the Chickasaw Nation, served as its governor during pivotal times. Born on August 22, 1817, near Pontotoc, Mississippi, Harris’s journey from a humble beginning to a prominent leader is a tale of resilience and dedication. His early education was shaped by missionaries and small schools that provided him with the basics of English education. Despite the early termination of his formal schooling, Harris demonstrated a profound capacity for leadership and cultural navigation, bridging the Chickasaw and American worlds. He worked variously as an interpreter, a clerk, and a land agent, roles that utilized his bilingual skills and intimate knowledge of Chickasaw and settler cultures. His political career was marked by efforts to protect Chickasaw interests during tumultuous times, including their forced removal west. Harris’s repeated election as governor speaks to his leadership qualities and the respect he commanded among his people. His life and career offer deep insights into the challenges faced by the Chickasaw Nation during the 19th century, a period of profound change and adversity.

Biographical sketch of Cyrus Harris

Ex-Governor of the Chickasaw Nation.

Cyrus Harris, who was of the House Emisha taluyah (pro. E, we, mish-ar, beyond, ta-larn-yah, putting it down) was born, as he stated to me, three, miles south of Pontotoc, Mississippi, on the 22nd of August 1817. He died at his home on Mill Creek, Chickasaw Nation. He lived with his mother until the year 1827, when he was sent to school at the Monroe Missionary Station, at the time that Rev. Thomas C. Stuart, that noble Christian missionary and Presbyterian minister, had charge of the school, and in which many Chickasaw youths, both male and female, were being- educated. In 1828, he was taken, to the state of Tennessee by Mr. Hugh Wilson, a minister also of the Old School Presbyterian faith and order, and placed in an Indian school located on a small stream called Roberson Fork, in the county of Giles. This humble little Indian school was taught by a man named William R. McNight. Cyrus, at the close of the year 1829, had only been taught the rudiments of an English education, to spell in the spelling-book and read in the New Testament. In the early part of the year 1830, he took up the study of geography and reading in the first and second readers, which terminated his school boy days, as he returned home that year and never attended school again. When he returned to his home he found it vacated; but learned that his mother had moved to a place near a little lake then known as Ishtpufahaiyip (pro. Isht-poon-fah, Horn, haiyip, lake), eighteen miles southwest of the present city of Memphis, Tennessee. Thither he at once; turned his steps, and soon found his mother in her new home, where he remained but a: short time (then thirteen years, of. age), as he was soon sent to stay a while with art old lady as company for her, whose husband a short time before, had been killed by a Choctaw who had been adopted by the. Chickasaws.

Cyrus remained a few months with the bereaved widow, but .he became, so lonely there being: no neighbors, nearer than three, miles, that his boyish heart could endure it no longer; though he amused himself the best he would by hunting and shooting rabbits, squirrels and birds with his bow and arrows, often visiting his mother living a few miles distant. He again returned to his mother but to remain a short time as before; as his uncle by marriage, Martin Colbert, a most excellent man employed him to come and assist him with his stock.

Cyrus Harris who spoke both the Chickasaw and English languages, having learned from a friend that there was a demand for interpreters, sought at once the land office established at Pontotoc, three miles from the home of his birth, and fortunately succeeded in securing a position as clerk in a dry goods store, and also to interpret for one John Bell, who was then Surveyor General, but kept a trading house. He remained only a short time as clerk, for he soon obtained a more lucrative position in that of acting as interpreter for the deputies of John Bell and one Robert Gordon who were partners in buying lands. At this time the United States Agent and the Chickasaw commissioners were busy in locating lands. Land speculators followed up the agent and commissioners, that no opportunity might be lost in which a profitable speculation might be made.

Cyrus Harris now became an indispensable personage in the firm of Bell & Gordon. In 1839 the land sales were brought to a close and the Chickasaws were then informed, without equivocation, that their room was more desired than their presence; and as nothing more could be made out of them, they could now go West or to the devil, it made no difference which, so they were expeditious in the matter. Cyrus Harris was appointed as one of the interpreters to in form the Chickasaws to meet at once in council and appoint the day in which they would depart from their ancient heritage, now passed into the hands of the Philistines; and the long cherished and loved scenes that make life doubly dear to the heart. The Whites having now no longer needed of the cloak of friendship and good will to hide the hideous deformity of their hypocrisy hurled it from them with un-assumed disgust and stood forth in their native ugliness.

The Chickasaws at once took up their line of march westward, feeling that rather than abide such a tempest of rascality as was daily exhibited before their eyes in the wild and crazy scuffle for a few acres of earth by which to quench their raging thirst for gain, they would flee even from heaven did such a stream of strife and corruption threaten an entrance there.

On the first of November, 1837, Cyrus Harris, with his mother and a family of friends, left forever their homes and native country, now in the clutches of their assumed friends, the Whites, to join the emigration, then awaiting transportation at Memphis, Tennessee, which soon arrived, and the greater part of the Chickasaws, under the jurisdiction of one A. Upshaw, the emigration agent, left for Fort Coffee, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, by way of steamboats. Cyrus Harris and mother, with a few other families, went through by land to Fort Coffee. When they had arrived there they learned that their friends were encamped near Schullyville (Schully, a corruption of the word Tuli the full word being Tuliholisso money paper, or paper money; a place where the Government paid them their annuities), but the “ville” part of it is unquestionably English.

Harris remained in camp at Schullyville about two weeks; then, with several families, started to find a desirable place for settling, and finally located on Blue River. This was in 1838. While living there he was induced to ” enter the political arena of his country. In 1850 a council was convened at Boiling Springs, in Ponola (Cotton) County, in which he was appointed to accompany Edmond Pickens to Washington City to arrange some national business, which proved ineffectual from some injudicious recommendation.

On returning home Mr. Harris sold his place on Blue River and settled at Boggy Depot. He resided there a year, and again sold out and moved to a point on Pennington Creek, about a mile west of Tishomingo, where he remained until November, 1855. Not satisfied there, he once more sold and moved to a place on Mill creek, where he still lived in 1884. In; 1854 he was again appointed a delegate, with several others, to Washington City. In 1856, after the adoption of the Chickasaw Constitution, he was elected governor of the Chickasaw Nation. Having served two years, with commendable discretion and sound judgment, he was re-elected, and filled the gubernatorial chair for two more years, sustaining himself with equal credit and honor, after which he was elected two more terms, serving his people with the same integrity. During his four terms of eight years, peace, harmony and prosperity prevailed throughout the Chickasaw Nation.

In 1876 ex-Governor Cyrus Harris was again brought be fore the Chickasaw people as a candidate for the office of Governor, but was defeated by his opponent, B. F. Overton, who served his people faithfully and satisfactorily through his first term, and at the next election was re-elected. In 1880 Cyrus Harris was again brought out by his friends, contrary to his wishes, and was pronounced elected by the Legislature, but, it was said, votes were counted out just enough to illegally elect his friend, B. C. Burney, a man highly esteemed by the people. Ex-Governor Harris then and there announced that he had forever withdrawn from the political field, and he has strictly adhered to his determination.

Since writing the above the sad tidings of the death of ex-Governor Cyrus Harris, that noble patriot and true philanthropist, was announced in the following obituary:

“Died at his residence, Mill Creek, Chickasaw Nation, Friday, the 6th, Cyrus Harris, ex-governor of the Chickasaws. He was buried on the 7th inst. at the family cemetery in Mill Creek.”

“To record the passage from life to eternity is the saddest and gravest duty that falls to the lot of the journalist. The more so, when he announces the death of one whose; loss will be deeply and widely regretted; one beloved of all men, whose place can never be filled in the homes and hearts of his people. In recording the death of ex-Governor Harris, we are fully aware of this fact; for not within the range of man s recollection has any member of the Chickasaw tribe impressed himself so favorably, so deeply and effectually upon his generation.

“His public and private character were wrought in the same mould; both equally incorruptible. The low, the base, the avaricious, were elements foreign to his existence, Awhile the chambers of his heart were ever lighted for the reception of such warm impulses and philanthropic ideas as are rarely met with, save in natures of the noblest type. Despite his progressive ideas, Cyrus Harris was an Indian in the truest sense, a patriot and a leader of his people. His country was his greatest care; so whether engaged in legislature, in administration, or dwelling peaceably in his humble cottage, his heart and brain were alike harnessed to his countries welfare. His generosity and his self-sacrifice were finely displayed in his last executive act. His election by the people being disputed by the House, in order to avoid political trouble, he withdrew and retired into private life.

“There is no reward in this world for that which is in corruptible; naught save the approbation of the good and the wise. But how meager that reward, after a lifetime of unselfish labor. Therefore, may the wish grow spontaneously in every sorrowing heart that a new and everlasting recompense lays, within reach of the departed chief.

“To the grief-stricken relatives of Governor Harris, and to the Nation that mourns a true friend and a wise Counselor, the Independent offers its most sincere and lasting, sympathy.”

Verily, that no truer words than the above ever, formed an obituary, may safely be said, is the, universal response of all who were personally acquainted with him who forms this subject, a man, though a North American Indian, of whose race ignorance and egotism declare there is none good but those dead, yet unsurpassed in noble virtues, moral stamina and social graces; and whom neither flatteries, nor censures, proffered wealth nor homes, could seduce from the path of virtue and honor.

Logan Colbert married a native Chickasaw woman by whom he had four sons, George, John, William and Levi; all of whom arose to prominence and exerted a salutary influence among their people, and became men of authority and distinction. He also had another son by a second marriage, named James, who fell not behind his distinguished brothers.

Why Logan Colbert came to cast his lot at so early an age and so far from the land of his nativity, among the people so remote r from all the English settlements, are problems that never will be solved, though it may be conjectured with some show of probability, that he came with some of the early English traders and adventurers who assisted the Chickasaws in their wars against the French. At an early day he was a renowned leader among them, and to that degree of celebrity, that one of the names given to the Mississippi river by the early French writers, during the days of their wars with that people with whom he had identified himself, was Rivere de Colbert sustaining the conjecture, that -Logan Colbert was the name of the most famous chief among the Chickasaws; who at that time swayed the sceptre of absolute authority over the country along” the east banks of the Mississippi river to the great annoyance and danger of the French in ascending and descending that mighty stream. Though little else of the life of Logan Colbert has escaped oblivion, except he lived, he died; yet his name has been handed down to posterity in that of his noble line of descend ants, who figure upon the pages of Chickasaw history as being among the influential families of that Nation.

Colonel George Colbert, in the prosperous days of the Chickasaw people, lived three or four miles west of what is now known as the town of Tupelo, Mississippi, (Tupelo is a corruption of Tuhpulah To call or shout). George Colbert became to be the wealthiest of the four brothers and was, in his personal appearance and manners, very prepossessing. He did not act in any public capacity, yet he exerted a great personal influence as a private citizen. He was a true conservative in sentiment and in spirit. He regarded his people, the Chickasaws, uninfluenced by the Whites and uncontaminated by their vices, as having reached the point of national progress most favorable to virtue and earthly happiness; therefore, he opposed all innovations as an evil which wisdom, virtue and patriotism loudly disapproved; and seemingly with much justice, since the Chickasaws (like the Choctaws) were a virtuous people before the Whites came and introduced their vices among” them; therefore, he was an out spoken enemy to missions, to schools, to whiskey, in short, to all the good as well as the evils that were being imported into his then happy country, having learned by experience and observation that the evil introduced by the whites counterbalanced the good in point of amount as five to one; yet he failed to shape the policy of his Nation in accordance with his views, for the missionaries came and introduced. Christianity and established it upon a firm basis in spite of the whiskey-traders and others who followed closely in their wake, with all their concomitant vices, who seemed to delight in thwarting the noble efforts of those devoted and self-sacrificing men of God (even as they do at the present day), that they might the more easily drag the Indians down to their own degraded level.

To escape the demoralizing influences of such degraded characters, and not the missionaries, did George Colbert advocate the emigration of his people to the remote wilds, of the west, where he hoped and believed the evil tide of innovation would be arrested which threatened to engulf his people, if they remained in their ancient domains, and sweep away in its mighty current of iniquity all the Chickasaw old land marks of their moral foundations. In that distant land, so remote (then considered) from the whites, he fondly cherished the belief that his nation would throw off the manners and customs of the whites, which they had already adopted, and return to the old paths of that simplicity of life in which their progenitors had walked for ages unknown. But he was doomed to disappointment, for not only the missionaries went with his people to their new homes to be found in the west, but the whiskey peddler and his congenial spirits, not to be thus cheated out of their victims, soon, followed on their track with the zeal of their master, the devil, where they have been hovering around the outskirts of the Chickasaw Nation, and often sneaking within, from that day to this, as they have been doing around in the territories of all Indians; and though the Chickasaw people, alike with all their race, have had to fight the devil and his imps in an unequal contest, being hampered by the government of the United States in its, laws regarding its worthy sons of freedom, whose-proclivities lead them to indulge their “glorious independence” regardless of all laws and every principle of truth, justice and honor, in regard to whiskey in particular; yet the Chickasaws and Choctaws have made that wilderness, to which they were banished, blossom as the rose, while George Colbert sleeps beneath the soil under the shades of the forest trees in the present country of his noble people, the Chickasaws. He lived and died firmly adhering” to the principles which he believed to be the greatest interest to his country. He was a true patriot, and loved the simple manners of the olden times, and could not yield them to give place to modern customs with their accompanying vices; and who can blame him? Alas! The Indians, everywhere on this North American continent, have been compelled to pay a higher price for the few crumbs of Christianity that they have been allowed to pick up and convert to the use of their starving- souls than any race of people that ever lived, since the divine command of the world s Redeemer bade his apostles, “Go ye into all the world and preach my Gospel.”

General William Colbert was a man of a military turn of character, and in that capacity rose to considerable distinction in the “Creek War” of 1814. He won the confidence of General Andrew Jackson in that war, by his manly bearing and noble conduct, and was presented by Jackson, as a testimonial of his esteem, with a fine military coat made after the American style, which Colbert carefully kept to the close of his life as one among 1 the most highly treasured relics of the past, and only wore it on important national occasions. He lived a few miles south of a little place then known as Tokshish a corruption of the word Takshi, (bashful). He died in 1826, honored by his people while living-, and mourned by them when dead as an irreparable national loss. .

Major Levi Colbert resided near a place then known as Cotton Gin. He was truly a man wise in the councils of his Nation and valiant in defense of his Nation s rights. In early manhood, or rather in boyhood, he was elevated by an act of gallantry to the high position of “Itta wamba micco,” as has been so oft published by different writers, and meaning, as given in the wisdom of their interpretation, “Bench Chief, or King of the Wooden Bench.” There is no such word in the Chickasaw language as “Itta wamba micco,” and it can be but the fabrication of imaginative ignorance. The Chickasaw words for Bench Chief (if there ever was such a personage among them) would be, “Aiobinili (a seat) falaia (long) Miko (chief) pro. Ai-ome-bih-ne-lih-far-li-yah: Meen-koh, The chief on the long seat or bench in our phraseology, The Chief in the Chair of State.

Major Levi Colbert’s act of gallantry, by which he was at once elevated to the high position of chief, consisted in having defeated, when but a youth, a war party of Muskogee’s who had invaded the Chickasaw Nation, at a time when all the warriors of the invaded district were away from home on a hunting excursion. Young Levi at once collected the old men and boys and formed them into a war company and started for the depredating Creeks, whom he successfully drew into an artfully planned ambuscade, by which all the Muskogee’s were slain, not one being left to re turn to his own country and tell of their complete destruction! The little stream upon whose banks the battle took place was afterwards called (so says a writer in one of his: published articles) “Yahnubly,” and gives its signification as “All killed”; but unfortunately for his erudition, no such word is known in the Chickasaw language. There is, how ever, the word yanubih (pro. yarn-ub-ih) in their language but its signification is ironwood. While the Chickasaw words for “All killed” (same as the Choctaw) are moma-ubih; the land or place where all were killed.

When the warriors returned from their hunt and learned of the battle and to whom the safety of their families was due, and also the honor of the victory, a council was immediately called and the young hero summoned to attend; when/he appeared and the statement of facts had been laid before them, they, without a dissenting voice, and “as men who quickly discerned true merit and knew how to appreciate it, elevated him to the responsible position of a chief in their Nation.

The following publication appeared a few years ago as a valuable piece of Chickasaw history: “Ittawamba was the name of an office. The word signifies King of the Wooden Bench. The individual who held the high title was elected by the national council. A part of the imposing ceremony by which the officer elected was initiated was as follows: At a given signal he jumped from a wooden bench to the floor in the hall of state where the magnates of the Nation sat in conclave. At the moment his feet touched the earth the whole of tire assembly exclaimed Ittawamba! The honored individual who heard this voice became the second magistrate of the Nation. Thus he received the orders of Chickasaw Knighthood, Ittawamba micco, or Bench Chief.”

No doubt of it. But the greater mystery is, how anyone could jump “from a wooden bench to the floor in the hall of state,” and the moment his feet touched the earth,” not to become instantly a notorious “Bench Chief.” Verily, a problem that must be left for solution to the unprecedented wisdom of the author of the above historical piece of information.

But the whole article is such an exhibition of pitiable nonsense, that in reading- it to some Chickasaw friends, they all exclaimed: “What a fool!”

The most ridiculous, absurd and utterly false articles ire continually appearing in print, in regard to the Indians, from the pens of those whose knowledge of that unfortunate people, against whom lies enough have been fabricated and published to satisfy the devil, is about as much as might be expected to be found in an African Bushman.

But be what “Ittawamba” may, nevertheless the young initiate., Levi Colbert, .after his initiation into its wonderful mysteries, proved himself worthy to be not only a “king of the wooden bench,” but also, by his talents, purity of principles, energy and force of character, a king upon a regal throne to bear rule over a nation. For several years he shaped the policy, and presided over the destinies of the Chickasaw people with wisdom and discretion. ,

On the 27th and 28th of September, 1830, the Choctaws, by a treaty with John Coffee and John Eaton, United States commissioners, ceded their lands east of the Mississippi; river to the United States. Major Levi Colbert, having heard what they had done, immediately called upon his friend, Mr. Stephen Daggette, and asked him to calculate the interest for him of four hundred thousand dollars at five, six, seven and eight per cent. The Choctaws had taken government bonds at five per cent. Major Colbert at once seeing that they had been badly and most outrageously swindled, exclaimed in a loud and highly excited tone of voice, “God! I thought so.” He then informed Mr. Daggette that he was anxious to obtain the calculation, that he might: be enabled to explain it to his people in their own language. He also stated to Mr. Daggette that “the United States would soon make an effort to buy the lands of the Chickasaws also, and I want to be ready for them.”

This conversation between Levi Colbert and Mr. Daggette took place two years before the treaty with the Chickasaws, which was made on the 20th of October, 1832, at the house of a Chickasaw called Topulka a corruption of Tah-pulah; (to halloo or make a noise), but was known, says a writer of the yahnubbih and Ittawamba order of expounders, in his publication, as “Pontaontac,” which he also interprets as signifying “Cat Tail Prairie”; but unfortunately for him also, the Chickasaw words for his classic name “Cat Tail Prairie” are Kutus Hasimbish Oktak (pro. Kut-oos (cat) Har-sim-bish (tail) Oke-tark (prairie); therefore he also must seek elsewhere than in the Chickasaw language for his “Ponlaontac” and its signification “Cat Tail Prairie,” as there is no such word in the Chickasaw language, nor in any other North American Indian language, it is reasonable to sup pose. Pontotoc, the name of a town in north Mississippi, is a corruption, as has been before stated, of the words Paid Tukohli: grapes hung up; hanging grapes.

But such are the gross and ridiculous errors made by those of the present age who not only prove their terrible ignorance by their unmerciful butchery of the Indian languages, but equally so in the exhibition of their shameful prejudice unreasonably cherished against that unjustly persecuted people, concerning whom, in every particular, they assume to be infinitely wise; and though totally ignorant of the subject, presume to talk and write about them with arrogant duplicity to the infinite injury of the Indians and disgrace of their languages.

When the United States had resolved to gobble up the Chickasaw country also, as they had the Choctaws two years before, John Coffee was sent to the Chickasaw Nation to order Ben Reynolds (the Chickasaw Agent) to immediately assemble the chiefs and warriors in council to effect a treaty with them.

Three treaties (or rather articles) were drawn up, but were promptly rejected by the watchful and discerning Chickasaws. Then the fourth was written by the persistent Coffee; but with the following clause inserted to catch the noble and influential chief, Yakni Moma Ubih, the incorruptible Levi Colbert, which read as follows; “We hereby agree to give our beloved chief, Levi Colbert, in consideration pf his services and expense of entertaining the guests of the Nation, fifteen sections of land in any part of the country he may select.” “Stop! Stop! John Coffee!” shouted the justly indignant chief in a voice of thunder; “I am no more entitled to those fifteen sections of land than the poorest Chickasaw in the Nation. I scorn your infamous offer, clothed under the falsehood of our beloved chief, and will not accept it, sir.” A frown of disappointment momentarily rested, no doubt, upon the face of Coffee.

Then a fifth treaty was written out by Coffee, and the council again called together to consider upon its merits; and which, after due deliberation, was finally accepted. The Chickasaws agreed to take United States bonds, but were unable to satisfactorily comprehend the six percent promised them, until their interpreter, Ben Love, illustrated it as a hen laying eggs. Those one hundred dollars would lay six dollars in twelve months, which they at once fully understood. But Ah! had that old hen inconsiderately roosted one night in or near the Great Temple of American Liberty here would she have appeared ere the dawn of the returning morn? Echo but answers, “Gentle shepherd tell us here”!

Ishtehotopa, the king, first walked up with a countenance that betokened the emotions of one about to sign his countries death warrant, and with a sad heart and trembling hand made his mark. Then Tishu Miko advanced with solemn mien and did likewise; then the other chiefs with countenance sad and forlorn; and last of all, the pure, le noble Levi Colbert, whom gold could not buy, or cause to ever from the path of honor.

Soon after the treaty had been signed, Major Levi Colbert stated to Mr. Daggette he was not satisfied with some clauses in the treaty, which he did not at first correctly understand. Mr. Daggette advised him to go immediately to Washington and get it changed to his satisfaction before it was confirmed by the Senate. Colbert, with other delegates, started immediately to Washington City, but only got as far as his son-in-law, Kilpatrick Carter’s, in Alabama, where he as taken sick and died, to the great sorrow and loss of the Chickasaw Nation. The other delegates continued their journey to Washington, and secured the desired alteration, in the treaty.

What attractive pictures for an art gallery would the scenes presented at that treaty between the Chickasaw Nation and the United States in 1832, at the humble home of Tahpulah, and the one two years before between the Choctaws and the United States. The United States, a great and powerful nation, professing to be governed in all its actions y the principles alone of Christianity. The Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations, weak, poor and unlettered, making no processions to intellectual attainments whatever. The former sing its skilled ingenuity in deception, misrepresentation and falsehood to defraud; the latter, sustained by truth and honor, watching and deliberating how best to successfully meet the dire attack and come out of the unequal contest with that alone that justice awards. The one representing the people of civilization, and Christianity; the other, the people of unpretending and unsophisticated nature. The one offering bribes: the other refusing to be bribed. The one called Christian; the other called heathen. But God is the judge.

But, injustice, it must and shall be said of the Chickasaw Agent of 1832, Benj. Reynolds, that he was an honest man. As agent to the Chickasaw people for the United States Mr. Reynolds annually paid them twenty thousand dollars for several consecutive years as annuity. Previous to the treaty Mr. Daggette affirms he assisted Mr. Reynolds in paying to the Chickasaws their annuities, and that Mr. Reynolds distributed the last cent among” them, giving to each, his or her dues honestly and justly, though every opportunity was offered to defraud them, and lived and died an honest and pure man; and then, no doubt, went above to receive the glorious welcome, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant.” Such a government agent to the Indians at the present day of boasted civilization and progress would be a national prodigy, and ought to be, if possible to be found, set up in a glass case at all the expositions the world over as worthy to be ranked with; the Eight Wonders of the world as the meritorious Ninth.

James Colbert, the youngest of Logan Colbert s sons, was also, as his renowned brothers, a man of great integrity and firmness of character. He acted, for many years, in the capacity of the national secretary. The archives of the Chickasaw Nation were placed in his hands for safe keeping, the majority of which being in his own hand writing; and truly it may be said, antiquaries, in coming years of the far future, may decipher with much interest and profit, the documents written by James Colbert.

Thomas Love, who, at an early day, also identified himself, with the Chickasaw people by marriage, had six sons, viz: Henry, Benjamin, (who acted in the capacity of interpreter for the Chickasaws for many years) Isaac. Slone, William and Robert. All of who have died, except Robert, who was known as Bob Love.

The Chickasaws, in common with all the Indians of the South, possessed many fine orators whose orations were eloquent, persuasive and full of animation; and it is a question of great doubt if the White Race ever found” among their uneducated citizens a single orator who could respect ably compare with hundreds of unlettered orators among the Indians of the South, or even of any of the North American Indians. As a race of people the Chickasaws were tall, elegantly proportioned, erect and muscular, with a square forehead, high cheekbones, compressed lips and dark penetrating eyes. In their councils (like all other Indians) grave and dignified, and never indulged, under any circumstances, in noisy harangues; they spoke slowly, distinctly and to the point. It is, and has always been, the universal declaration and belief of the Whites that the North American Indians are taciturn, grave, and never smiled or indulged in merriment or laughter under any circumstances. This is a great error, and but a repetition of the same old edition of the same old story, which, like all else said and written and published about the North American Indians, was begotten by ignorance, conceived in duplicity and brought forth in prejudice to say the least of it. Never did a more jovial, good natured and lighthearted race of people exist upon earth than the North American Indians. True, they were grave and taciturn in the presence of strangers, and the reason is obvious. The white people (excepting the old missionaries of the long ago), in all their actions among them, and in all their conduct toward them, have ever and everywhere assumed an air of superiority over them, which the Indians have ever justly denied; and which justly created in their minds pity for the foolish self-conceit and egotism of the Whites, which seemed to them a lamentable weakness unknown and unseen before in the human race; and also created equal contempt for such a display of presumption and evident want of sound judgment, or rather of common sense; the natural consequences of which were taciturnity and gravity when in the presence of such self-imagined au gust specimens of humanity.

Even many ministers of the gospel, sent among the Indians by the various denominations of the states to preach to them, preach themselves instead of Christ, by indulging in unmistakable bantam rooster airs of the superiority of the whites over the red, detailing their opinions concerning the progressive renovation that would have certainly ensued in every department of their national and social affairs had the Indians, from their first acquaintance with the White Race, had the good fortune to have enjoyed the advantages of their ethical wisdom and profound theological erudition. Often have I been an eye witness to many such exhibitions of clerical imbecility during my frequent sojourns among the Chickasaws and Choctaws within the last ten years; and though as loquacious as Brazilian parrots, yet “Pretty Poll wants a cracker” was in substance, the climax of their sermons, as Self was so highly esteemed a personage that they were oblivious to all else.

But such was not the style of men, who in 1815-20, pro claimed the glad tidings of great joy to the Southern Indians. Far from it. They were men of deep piety; of firm resolutions; of Christian humility; of self-sacrificing zeal; of humble submission to the will of God; of unshaken faith in the promise, “Lo! I am with you even to the uttermost parts of the earth”; of indefatigable energy to lead the Red Race, long wandering in the path of moral darkness, into the fold of Christ; of unalloyed love for their souls and desire for their salvation; of un-assumed sympathy for them as human beings to whom the knowledge of man’s Redemption through the Son of God had never been proclaimed; of admiration for their many virtues unsurpassed by any nation of people upon earth, to whom the Gospel of Jesus Christ had never been preached. Therefore, they visited them at their homes in their humble log cabins; sat down among them in the family circle upon the bear skins spread upon the cleanly swept dirt floor; and there proclaimed to them concerning Him of whom Moses and the prophets wrote; slept upon their bear and panther skins in humble gratitude for as much, when remembering their Savior had not where to lay his head; ate of their venison, tafulatobi ibulhto (hominy mixed with beans), and botahkapussa (cold flour).

They sang and prayed with them in the morning; then went with them to their little fields of growing corn and instructed them in the art of agriculture and imparted to them new ideas of home comforts. Thus they taught them everywhere and on all occasions, both by precept and example. They acknowledged them as human beings; and for them also Christ purchased salvation upon the cross. Self was not in all their thoughts, only to preserve it for usefulness in the cause of their Divine Master in bringing the Red Race of the south into his fold. What was the result? Mutual confidence and disinterested love and friendship prevailed everywhere between the appreciative Indians and those missionaries, men and women, all true servants of God; and the five civilized tribes (as they are now called) stand today as living monuments of the salutary effects of the teachings of those self-sacrificing men and women of seventy-five years ago true and devoted servants of Jesus Christ in the salvation of their fellow men found and acknowledged in the North American Indians.

The ancient Chickasaws were the most famous trailers of all the southern Indians. Their skill in this art was truly astonishing, and seemed almost superhuman. I call it an art; and it is as much so as is painting or sculpture, while almost as few become proficient in it as in the handling of brush or chisel. Art, or by whatever name it may be called, yet it requires constant practice and much knowledge of nature, in all its variations, to learn it thorough; and I believe it more natural for an Indian to become a trailer of man or beast than a white man, as they seemed to acquire by intuition what the white has to learn from a life-time of study. Here and there, I’ll admit, a white man may be found who becomes an expert, yet the boasted leaders of civilization fall far behind the natural-born trailers, the North American Indians. Who could learn, through the medium of books or any other way of instruction, but that of a life time experience, to determine the age of a trail of man or beast correctly, or tell the number of an enemy and how long” since they had passed the spot which you may be examining? Yet the ancient Chickasaw warrior, in his palmy days seventy-five years ago, could do it, and even what tribe of Indians had made a given trail, its age, and all the particulars as correctly as though he had seen them pass. Truth fully did an Indian once exclaim:

“White man travel with his eyes shut and mouth open,” alluding to his propensity to talk. “Indian travel all day; say nothing, but see everything.” How true! Nothing escaped his observation, whether alone or with others; while the white man talks incessantly and sees nothing but the general features of the things he is passing; therefore, can scarcely retrace his steps for any great distance in a country he has never traveled before; while it is impossible to lose an Indian in any country, no matter how strange or new. No matter how difficult or circuitous has been the route by which he has arrived at any place, the Chickasaw would, with ease, find his way back whence he started without hesitating a moment which course to pursue. When asked how he did it he may reply, Siah (I am) a chuffa [one) kutah (who) ikhanah (remembers); though often he would make no reply. No matter how loquacious he may have been at home or else where, when upon the warpath or the chase he was silent. The North American Indian was nearly as certain in predicting the weather, as a barometer, and his knowledge of the characteristics of the wild animals of his ancient forests would be a prize indeed to the naturalist.

As warriors and hunters the Chickasaws of seventy-five years ago had few equals, but no superiors, among the North American Indians. They were unerring marksmen with the rifle and capable of enduring seemingly incredible fatigue. They would follow the tracks of their game and the signs left by their human enemies for hours, where the eyes of the white man would not detect any sign of a footprint whatever. When hunting or upon the warpath, if they came upon deserted campfires or human footprints they could tell to what tribe they belonged and whether friends or foes.

As an illustration of their skill in discerning and interpreting landmarks and signs, I will here relate a little incident proving the wonderful skill and ingenuity displayed in ascertaining facts with regard to anything of which they desired to inform themselves.

In the years of long ago, a Chickasaw had a ham of venison taken from his little log” house in which he kept his stock of provisions during the absence of himself and family. He described the thief as being a white man, low stature, lame in one leg, having a short gun, and accompanied by a short-tail dog. When requested to explain how he could be so positive, he answered: “His track informed me he was a white man by his shoes, Indian wear moccasins; he stood on the toes of his shoes to reach the venison ham, which told me he was a low man; one foot made a deeper and plainer impress upon the ground than the other as he walked, which told me he was a lame man; the mark made by the breech of a gun upon the ground and the one made by its muzzle upon the bark of the tree against which it had leaned, told me he had a gun and it was a short gun; the tracks made by a dog told me of his presence; and the impress he made where he sat upon the ground to the end of that made by his tail, as he wagged it, was but a finger s length which told me the dogs tail was short.” What white man would ever have thought to look for, or discovered such evidences in identifying a thief?

Among the ancient Chickasaws, descent was established in the female line; thus the ties of kinship converged upon each other until they all met in the granddaughter; and thus every grandson and granddaughter became the grandson and granddaughter of the whole tribe, since all the uncles of a given person were considered as his fathers also; and all the mothers sisters were mothers; the cousins, as brothers and sisters; the nieces, as daughters; and the nephews as sons. They, as all their race, believed in the existence of one great, everywhere present and over-ruling spirit, whom they held in the highest reverence, and devoutly worshiped; as to him were attributed the gifts of peace, prosperity and happiness, abundant harvests of corn, beans, pumpkins and success in war and the chase. They also equally believed in the existence of an evil spirit, to whom they attributed the cause of all misfortunes; and here came in the power and influence of the wonder-working “medicine man,” or “prophet,” who professed to have attained to a thorough knowledge of both good and evil spirits, and also the ability to command their influence for good or evil, by fasting and prayer and mystic ceremonies.

However, the usages, manners, customs, beliefs and habits of life, national and social amusements of the Chickasaws were, in many respects the same as the Choctaws, and what may be said of the one, may with equal truth be said of the other.

Among the ancient Chickasaws and Choctaws there was a tradition concerning- the origin of a little lake in Tibih swamp. Oktibihha County, Mississippi. This isolated lake which I have oft visited on fishing excursions, has long been known as Greer s lake, and is about a half a mile long and one hundred feet or more wide. The tradition is as follows: In the years of the long- past, many generations before the advent of the White Race, a Chickasaw hunter and his wife, with two little children, (a boy and girl) were camped in the Tibih swamp near a little hole of water formed by the roots of a fallen tree. One morning the hunter and his wife went out in pursuit of game leaving their children, as usual, in camp. On their return late in the evening, they were stupefied with horror and amazement to find that their camp was swallowed up by the earth, and this lake lay stretched over the spot. But while, gazing upon the scene perplexed and terrified, they beheld two enormous snakes swimming upon the newly formed lake and coming directly towards them, which, caused them to- flee from the spot in great consternation. The sudden formation of the lake was ascribed by them to some miraculous agent, and by the same power, their children had been transformed into the two great water snakes; and such was the credulity of the Chickasaws and Choctaws in the account given of the wonderful event by the Chickasaw hunter and his wife, that down through all subsequent years, even to the time of their emigration west, the lake and its immediate surroundings were held in superstitious awe. Nor would they live nor approach any where near it. Varied and many were the views concerning its strange and sudden formation; all, however, agreeing that it was brought into existence by the wrath of the Great Spirit, and became the abode of evil spirits ever after wards.

The ancient Chickasaws once practiced the custom of extinguishing the fire in every house in their Nation at the close of every year, and let them so remain during three successive days and nights, while the occupants retired to the woods where they remained. By this means they believed they would rid themselves of all witches and evil spirits; since, when they came three successive nights and found no fire they would conclude the family had left their former place of abode to return no more; therefore they also would depart to never return. Then all the Chickasaws returned to their homes, built new fires and were happy, being freed from the fear of witches.