When English settlers first arrived in Florida, shell mounds were endemic to coastal areas. Not much thought was given to them until the late 1800s when the Florida East Coast Railroad was being built. Stone suitable for making construction gravel was non-existent in much of Florida, so railroad construction crews substituted crushed shells excavated from Native American mounds. The shell mounds were so commonplace and unremarkable esthetically, no one questioned the practice. After the railroad was completed, newcomers flocked to Florida. This coincided with the advent of automobiles. The automobiles needed paved roads to transverse the swampy terrain of the Florida. Road construction contractors immediately found the seemingly inexhaustible supply of Indian shell mounds just as convenient a source of raw materials as the railroad crews had earlier. By the late 1920s hundreds of the mounds had been completely destroyed. The state highway department switched to engineered concrete paving containing crushed stone in the 1930s, but Florida homeowners continue to utilize crushed shells for driveways.

On Tick Island, near Jacksonville, FL contractors were merrily tearing away at another shell mound when workers found stone tools and weapons mixed with the shells. Word got out. Some amateur collectors began poking around the site looking for perfect spear points, ornaments and pottery. Before the ancient structures were totally destroyed, Ripley Bullen, a professional archeologist investigated the site.

Until recently, the hundreds of shell rings and mounds along the Atlantic Coast and shell mounds along rivers in the Piedmont were thought to be the remains of temporarily occupied ceremonial centers or seasonal camping spots. The very early dates of many sites influenced archaeologists to assume that they were only piles of shells and debris that arose spontaneously at feasting grounds. Perhaps some, or many, were. The first discovery to challenge this assumption was at Tick Island.

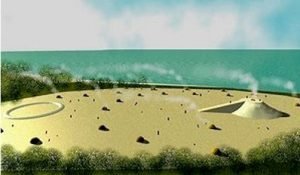

At Tick Island, formal burials with grave goods were found under a very large mound that was radiocarbon dated to approximately 3500 BC by archaeologist Ripley Bullen. The few archaeologists, who were even aware of his discovery, responded that the large mound was the product of repeated generations of temporary visitors, who piled up sand and shells over a hallowed spot in ceremonies. They continued to interpret all Archaic Period mounds and rings as “middens” or piles of accumulated debris. However, Bullen’s work indicated that much of the mound at Tick Island was built in a very short time. It is not clear what form of social organization or religious values would enable a community of fishermen and gatherers to construct such a large project in a few years, but they did.

The structures at Tick Island were begun almost as early as those at Watson Brake, LA (See article on Watson Brake.) They actually may have been completed prior to the time that work stopped at Watson Brake. Tick Island’s antiquity is surprising enough, but the form of its main mound is astounding. It predates the earliest Maya mounds by about 3000 years, and those of the Zoque (Olmecs) by 2300 years! Yet the mound is surprisingly similar in form to both the early Zoque and Maya mounds. It had a ramp leading to a flat top, where it is presumed that ceremonies were held. The mound was extensively damaged by erosion and vandalism.

Did the Zoque (Olmecs) migrate to Mexico from the Southeastern United States?

The Maya’s recorded on their stone stelae that the ancestors of the Zoque arrived in three great flotillas of canoes onto the coast of Vera Cruz, Mexico around the year 1600 BC. This is about the same time that Poverty Point, LA was settled. Up to this point in time, pottery was not made in Mexico. The Zoque apparently introduced the technology for making pottery. Indigenous peoples in what is now Georgia and Florida had been making pottery since about 2500 BC. The architecture of Tick Island, FL and Watson Brake, LA predate any structures in Mexico or South America. Did the first steps beyond being migratory hunters begin along the Gulf Coast of the United States, and then spread southward to Mexico, the Caribbean and South America. It is a tantalizing possibility.