The Klamath Indians now live upon a reservation in the State of Oregon, which lies within a somewhat larger area occupied by them long before their discovery by the white race. The reservation is in the southwestern corner of the plateau of eastern Oregon, at the eastern foot of the Cascade Mountains and near the southern border of the State. The rainfall of the region averages only about 20 inches a year, the greater portion of the moisture that comes from the Pacific Ocean having been precipitated in passing over the Cascade Mountains. Most of the Klamath Plateau is covered by forests of yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa), but toward the east and toward the south are tongues of treeless sagebrush country (Artemisia tridentata and other species of the same genus) which extend along the valleys into the timber from the sago plains of eastern Oregon and northeastern California, while about the lakes and marshes mentioned below are several large areas, originally lake deposits, which are now raised above the surface of the water and are covered with grass, but which are still too wet to have acquired a covering of timber. That portion of the Cascade Mountains opposite the Klamath Reservation is made up largely of volcanic rook, covered by a layer of pumice gravel and dust. With such a porous soil the heavy precipitation in the mountains is not carried off by surface streams, but sinks into the ground and appears upon the plain at the base of the mountains in innumerable large springs of very cold and very clear water, which has filtered for many miles down the mountain slopes. As a consequence, the Klamath Plateau, although having a comparatively small rainfall, is nevertheless well watered and possesses some of the most beautiful streams on the continent. The drainage from these springs and streams produces two bodies of water, Klamath Marsh and Klamath Lake, which furnish a wealth of game. The richness of vegetable life, particularly in Klamath Marsh, is no leas remarkable than that of the animal life, and the latter is in fact dependent upon the former, for the birds feed upon the seeds and starchy roots of the larger plants or upon fish or other animals that ultimately depend for their supply of food upon the minute algae with which the waters of the marsh and lake abound.

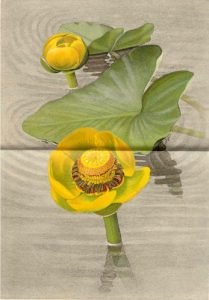

One of the plants growing abundantly in the marsh and less extensively in some of the bays of the lake, the great yellow water lily (Nymphaea polysepala), was a staple farinaceous food of the Klamaths in primitive times and now is regarded by them as a delicacy. An opportunity presented itself to spend a week at Klamath Marsh in August, 1902, and to see the Indians harvest their crop of wok’s (makes),a or waterlily seed. The industry is well preserved in so nearly its primitive form that a detailed record of it has seemed desirable and is herewith presented.

It is estimated that Klamath Marsh contains about 10,000 acres of solid growth of wokas. The plant is so vigorous and has such a habit of growth as usually to occupy an area suited to it to the complete exclusion of other characteristic and conspicuous marsh plants, such as tule and cattail. Certain plants associate themselves habitually with the waterlily, but these plants are for the most part submerged in the water, are inconspicuous, and subsidiary in their relationship to the waterlily, and in no effective or important way contest its spread. The principal of these latter plants are bladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris), mare’s tail (Hippuris vulgris), and pondered (Potamoyeton natans and other species).

- Awal

- Extracting Wokas Seeds by the Diachas Process

- Harvesting Wokas

- Klamath Names Connected with the Wokas Industry

- Lolensh

- Shnaps and Lowak

- Spokwas

- Stonablaks and Shiwulinz

- Wokas as an Article of Commerce