The 1,580 acres not farmed on account of deficient water supply may be farmed when a better and more economical mode of irrigation is adopted than that now practiced by the Indians. The 5,000 acres of timbered land is what is usually called mesquite land, from which the Papagos procure their fuel and sell considerable quantities from year to year. The 28,000 acres of mountain laud is next to worthless.

There are 94 heads of families on the reservation, and a little more than 5 acres of farming land (land that is farmed) are allotted to each head of a family. The 500 acres of allotted land are surveyed and staked out. The area of land cultivated is diminished, and no progress is being made in methods of farming. Most of their income seemed to be obtained from the sale of wood and hay cut on the reservation.

In the spring of 1890 the land was allotted to the Indians in severalty, and it may now be divided as to quality as follows:

| Land that is farmed | 500 |

| Land that is not now farmed on account of deficient water supply | 1,580 |

| Timbered land allotted | 5,000 |

| Mesa land, suitable for pasturage, allotted | 35,000 |

| Mountain land, including desert land that can be pastured 2 months in the year | 28,000 |

Agricultural Products Raised and Stock Owned by Indians for 1880-1890

| Products, Stock and Land | Number | Value |

| Total value of agricultural products | $7,170 | |

| Bushels or barley | 6,000 | 3,000 |

| Bushels of corn | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Bushels of vegetables | 1,050 | 1,050 |

| Melons | 200 | 20 |

| Pumpkins | 1,000 | 100 |

| Tons of bay cut | 100 | 1,400 |

| Total value of live stock | 4525 | |

| Horses owned by Indians | 200 | 3,000 |

| Cattle owned by Indians | 150 | 1,500 |

| Domestic fowls owned by Indians | 100 | 25 |

| Acres under fence | 14,000 | |

| Fence made during year (rods) | 7,700 |

All of the Papago Indians living on reservations are in a village near an Xavier (thumb. Their dwellings . are mostly rude adobe, with dirt roofs and few windows, and are almost destitute of furniture except the most primitive. There are only 14 comfortable adobe houses. Many of the Indians own farm wagons, though their farming tools are rude and unserviceable. The men all wear the civilized dress; the women also wear dresses similar to those worn by the whites, but leave off their shoes on ordinary occasions. It is claimed that 250 of the Indians living on the reservation are members of the Catholic Church.

Statistics of the Reservation Papagos

| Whole number living on the reservation | 363 |

| Males | 184 |

| Females | 179 |

| Children under 1 year of age | 33 |

| Males | 21 |

| Females | 12 |

| Number Married | 168 |

| Number over 20 years of age who can read | 10 |

| Number who can read and write | 10 |

| Number who can use English enough for ordinary conversation | 28 |

| Number of children of school age | 93 |

Papago Schools

The Catholic Church has provided 2 neat, well-furnished schoolrooms adjoining San Xavier Church, which will accommodate about 70 pupils. A school was maintained there during the year 1889 by the Sisters of the order of Saint Joseph, without pecuniary aid from the United States. The average attendance for the year ending June 30, 1890, was about 20. In addition to elementary studies the girls were taught sewing, crocheting, knitting, and minor household duties. A few of them became quite skillful in operating the sewing machine. The great drawback to the prosperity of the school was the irregularity in attendance. The school was again opened in September 1890.

There is what is termed a “contract school” located at Tucson, which many of the Papago children attend. The school is established and supported in part by .a missionary department of the Presbyterian Church. The buildings are large, airy, well planned, and adapted to the purpose required. The pupils seem well disciplined and clean. The government pays a stated sum annually to the school for each pupil in attendance as reimbursement for board and clothing furnished. The school owns 5 or 6 good buildings, all in good condition and well furnished also a farm of 43 acres. On account of lack of water but few garden vegetables are grown, but barley and wheat yield abundantly.

Some of the scholars are taught carpentering, painting, and plastering, and their work is quite satisfactory.

Papagos Living off the Reservation

Corrected text:

These Papago Indians live in the southern part of Pima County, along the southern border of the Territory of Arizona. Their language is similar to that spoken by the Pimas. They roam over a country about 100 miles in width north and south and about 125 miles east and west, and there are a few small villages over the Mexican border but near the boundary line.

The country in which they live consists of broad, open plains, divided by mountain ranges. The valleys or plains are arid, having no natural springs or running streams of water; yet after the summer rains these plains are covered with grass of a fine quality, and owing to the dryness of the air this grass is cured or dried on the ground and furnishes good, rich food for cattle during the remainder of the year.

The Indians select their dwelling places at the foot of the mountains near the mouth of the various canyons that open out into the plains. Small springs often flow through these canyons and sink into the sand. The Indians utilize these springs or sink wells into the sand, and thus secure the underflow from the springs. Their cattle feed out into the plains and return to these wells or springs to drink. Near these watering places, usually on an elevation, the Indians build their houses in their permanent villages of adobe, about 12 by 16 feet in area and about 8 feet in height. Small poles are laid on top and crosswise of the building, and on these are laid brush, with weeds or grass on the brush, the whole covered with about 5 inches of clay, which is impervious to water. The floor is of clay, and there is one doorway, but no windows. The doorway is sometimes closed with a dried beef hide. As a rule, they live on the outside of the house. The house contains no furniture except a little bedding and some cooking utensils.

Their food consists of beef, dried wild fruit, dried mesquite beans made into a kind of bread, and wild game. During the summer rains they raise some vegetables, which they dry for winter use. They also sell or trade cattle to settlers in the Gila and Santa Cruz Valleys for wheat and corn, which the women grind in their crude way into meal and flour. They have adopted the civilized mode of dress, and are gradually learning the use of soap.

The women of the tribe are virtuous and industrious, being in these traits far in advance of any other tribe in the Territory.

There are 4,800 of this tribe living off the Papago Reservation. With rare exceptions they are self-sustaining, have always been good citizens, and on many occasions have joined with the whites to assist in suppressing murderous Apaches. The principal occupation of the men is raising cattle and horses, and a little farming when they can find a piece of damp ground that will raise corn and vegetables, hunting, chopping wood around mining camps, and ordinary labor wherever they can find it. If there is any mixed blood in the tribe it is not perceptible.

There are several mining camps scattered throughout the country which these Indians inhabit, and in some of the large valleys wealthy men or companies have sunk wells 500 or 1,000 feet deep and established cattle ranches or ranges, and many Indians are employed about these camps and mines.

The country is somewhat difficult of access, as there are several mountain ranges running through it. The roads follow the valleys, and sometimes it is “a long way around where it is only a short way across.” These mountain ranges abound in game, which the Indians hunt.

A month’s travel in these Papago villages failed to reveal a single case of drunkenness, although there are frequent instances of drunkenness among Indians in the streets of Tucson. They have great numbers of horses and cattle, but it is impossible to form a correct estimate as to numbers. The horses are small and inferior, but the cattle are fully up to the average in size and quality.

These Indians as a tribe have always been exceptionally friendly to the white people. They have never received aid from the Government. The little religion they have is a conglomerate of Roman Catholicism, superstition, and Indian hoodooism. The Roman Catholic Church established missions among them more than 150 years ago.

The Reservation and Non-reservation Papago Indians, Pima Agency

Report of Special Agent C. W. Wood on the reservation and non-reservation Papagos of Pima and Cochise Counties.

Tribal Name

The Papagos and Pimas were formerly one tribe. Authorities differ as to the derivation and meaning of the name. One view is that Papago means “hair cut,” another that it means “baptized.” Neither of these meanings has any etymological basis or value. The most reasonable derivation of the term seems to be the following, derived from conversation with the oldest Indians: the division of the Pimas occurred from the labors of the Jesuit missionaries. When a considerable number of them had accepted the teachings of the missionaries, they were called, by way of distinction, Papagos, from the Spanish word for pope, “papa.” Baptism was involved in their becoming Christians, and hair cutting was an incidental result of the influence of the missionaries. Neither of these facts, however, can account for the name. On the other hand, the derivation from “papa” is etymological and consistent with the facts. They had become adherents to the pope. So far as I can learn, this explanation of the origin of the name has never been published.

The resident missionary at Sacaton gave still another derivation of the word Papago. He speaks and preaches in the Indian tongue, and thinks the name is derived from the word “pa-pa-cot,” meaning discontented. This could easily be corrupted into Papago. The Indians at an early date became much dissatisfied with the exactions and tyranny of the Jesuits, and this term was naturally applied to them.

The Papagos are a semi-nomadic tribe, their migrations being due to the peculiar character of the country which they inhabit. The exigencies of food, water, and labor are the principal causes of their temporary changes of habitation; but the extent of their migrations, and the localities which they occupy for varying periods, are within certain limitations. When, through the presence of wells or running water, the supply of that indispensable element is not failing, they migrate in search of food or labor.

When the water supply, which is procured from natural water holes or the earth reservoirs constructed by them, called tanks, where it accumulates during the rainy season, has been consumed, they remove to the vicinity of wells or running water found in the canyons of the mountains or in the deep valleys among the foothills. This migratory feature of their life greatly enhances the difficulty of an exact enumeration of the tribe.

The territory over which they range lies south of the Southern Pacific Railroad, in Arizona, and is about 100 miles in extent. Many thousands are also located in the State of Sonora, Mexico. They move back and forth at will between the two countries, and when a village is found in motion, inquiry alone can determine, and then not always with certainty, on which side of the line they really belong.

From various publications relating to Arizona, and from the statements of ranchmen, millers, traders, surveyors, and a census enumerator, quite conflicting and divergent estimates were obtained of the number of the Papagos. These estimates range from 3,000 to 7,000, while most of them agree on 5,000 or 5,500 as the real number. One difficulty to be experienced in their enumeration is that at any season of the year a village of permanent houses, evidently the abode of hundreds of Indians, may be found without a single inhabitant, not because it has been deserted, but because the inhabitants are gone temporarily, leaving no information as to where they have gone, for what purpose, or for how long a time, and it would be impracticable to wait until their return or to follow them.

The only available method for obtaining even an approximate estimate of the number of these Indians seemed to be to ascertain, as far as practicable, the number of their villages and the aggregate number of houses contained in them. Multiplying the total number of houses by the average number of inmates per house would give a reasonable result. By actually counting the inmates of many houses in several villages, and with the endorsement of the judgment of the enumerator, 5 was adopted as the average number of inmates per house. As not less than 4 nor more than 11 were found in any given case, it was decided that 5 would be a conservative average and insure a total within the actual number rather than in excess of it.

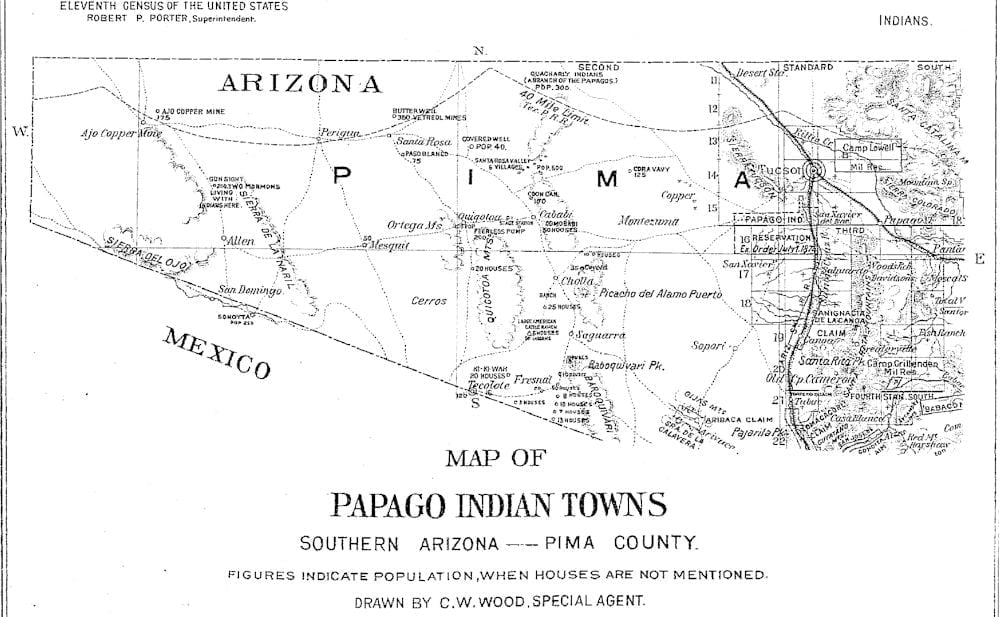

In the accompanying map, showing the route during a 10 days’ trip through the Papago country, Pima country is given on a scale of 7.5 inches to the mile. The villages are located from actual visitation or on information, with no effort at mathematical accuracy, but with the design of suggesting relations and distances. The trip was planned so as to reach as many villages as possible during the time allowed and to make a fair and correct census. The villages given in red are those actually visited, 5 of which were located by the Indians. The 2 villages marked with black, situated near the large ranch, were located but omitted by mistake. The accompanying figures indicate the number of houses in each village. The villages given in black were located through the courtesy of a trader among the Papagos, who is generally conceded to be the best-informed person in Arizona in everything which relates to the tribe. The figures in black indicate his estimate of the population of each village. His estimate of the numbers living in the villages actually visited in enumerating varied only about 25, more or less, from the numbers in the given villages obtained by the multiplication of the number of houses by 5. In the cases mentioned the population was from 350 to 500, and such close agreement gave additional credibility to both his and our estimate. (Map was not in color in the book.)

The number of resident Indians at San Xavier was ascertained exactly when the reservation was divided among them in severalty, and is perfectly reliable.

| Papagos at San Xavier | 363 |

| Papagos on line of expedition | |

| 447 houses, multiplied by 5 | 2,235 |

| Additional, estimated by I. D. Smith | 2,465 |

| 5,063 | |

| Additional, reported by C. W. Crouse, agent at Sacaton (Papagos on the’ old reservation at Gila Bend). | 40 |

| Resident at Sacaton reservation | 60 |

| Total | 5,163 |

Physical Characteristics of the Region

The territory covered by the Papagos in their migrations, and in which their villages are located, consists of mountain ranges and the intervening valleys. The soil of the valleys contains a considerable proportion of clay, so that it is all called adobe soil. In the mesas or plains, occasional strips of sand occur. Along the arroyos, or dry water channels, deposits of gravel are numerous. The arroyos become raging torrents during the rainy season, rendering travel impossible or dangerous during the temporary flood. The soil of the foothills is very rocky. Alkali is present in the soil in varying proportions, giving the characteristic name to the vast stretch of country known as the alkali desert. It is not the presence of alkali, however, that makes the desert, but the absence of water. An abundant water supply renders this alkali soil equal in fertility to any soil in the country. As it is, the valleys contain a great deal of arable land, which is evident from the great areas covered with grass, which form the stock ranges, and from occasional sections where weeds grow so luxuriantly after the rainy season as to overtop a man on horseback. Some portions of the valleys are covered with mesquite trees and bushes, and also sagebrush, but these sections produce abundant crops when irrigated.

Climate

The climate is very mild, being neither extremely cold in winter nor hot in summer. The mean average temperature during the summer of 1889 was 81.50, and during the winter of 1889–1890 it was 52.60.

Water Supply

There are occasional wells found among the Indian villages. Natural water holes are quite numerous, and by raising embankments of earth in favorable localities the Papagos make huge ponds or reservoirs, which they call tanks. These natural and artificial reservoirs are only serviceable for the temporary storage of water, and toward the last they become filthy mud holes. The Indians, however, continue to use the water as long as it can possibly be considered a fluid. In one place the Papagos have dug a well 80 feet deep, and with incredible labor have made a footpath from the top of the ground to the level of the water.

Water is found by boring at a depth of from 200 to 800 feet, but no flowing wells have yet been obtained in the territory. The water in the wells rises from 50 to 150 feet, and then is raised to the surface by steam pumps. The Indians, however, have not the financial resources with which to sink or operate artesian wells. When their tanks are exhausted, they remove with droves and herds to the valleys and canyons in the mountains, frequently crossing over into Mexico.

Timber

The varieties of timber within the Papago range are the willow, cottonwood, mesquite, paloverde, and on the southern and western mountain slopes, the oak. The mesquite is the most common timber, as it grows freely on the mesas. It rivals the hickory as firewood, throwing out great heat, and the coals retain fire even longer than coals of hickory. The mesquite, however, is very easy to cut, and is handled with far less labor than hickory.

Fruits and Nuts

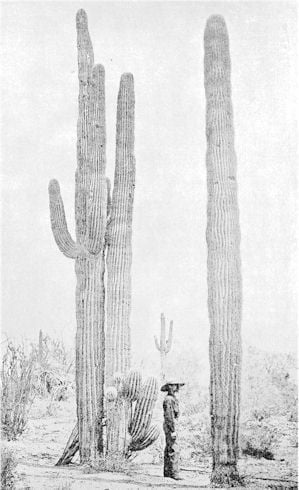

The sahuaro (giant cactus), which grows on the rocky soil of the foothills and covers the moderate mountain ranges, rises in height from 10 to 60 feet, and is a mass of vegetable matter, supported by an internal skeleton of ribs or poles of woody fiber. The fruit of this remarkable plant grows out of the top of the trunk and arms, and constitutes an important article of food, the Papagos almost living upon it during June, July, and a part of August. They gather it with long poles, and eat it either fresh or after it has been dried. They make from the juice a syrup and a drink which is slightly charged with alcohol. Although the ribs of the sahuaro are very valuable, the Indians never destroy the plant, and are greatly incensed if a white man cuts one down; but when the cactus dies and the vegetable matter dries, powders, and falls away, leaving the ribs exposed and bare, they are used as supports for the dirt roofs of adobe houses, for the sides of houses when plastered with mud, for poultry and pigeon houses, and other small structures.

The Papagos eat the fruit of the prickly pear cactus and make a syrup from its juice; from the mescal (sweet aloe) a highly intoxicating drink is made. The root, which is bulbous, grows partly under and partly above the ground, and when roasted it is very delicious, and great quantities are consumed by the Papagos. They dig out of the ground a vegetable which appears to be a species of wild onion, but they call it a groundnut, and relish it highly when boiled. A very useful plant found in large quantities, called the soap plant (amole), forms a substitute for soap.

The tannin root, resembling the sweet potato in appearance, grows in great profusion. It contains a large portion of tannic acid, and is a substitute for the astringent barks, hemlock and oak, which are used in tanneries.

Industry

The Papagos seem to be esteemed by the whites in general as the best Indians in the Territory. They are industrious, and are good help in mines, on ranches, in the harvest field, and on stock ranges. They easily learn the mechanical arts, and set and handle mining drills as well as white men. The engineer at the Quijotoa mines said that his assistant was a Papago, and that he was fully competent to run the engine.

In practical irrigation the Indians are conceded to be the superiors of the whites, and in their domain this is the foundation of agricultural skill. When properly educated, there can be no doubt of their ability to acquire the scientific principles of the art.

Food

In addition to the fruits, nuts, and flesh already mentioned, their food consists of wheat flour (usually formed by the women on a metáte) prepared in simple ways, parched wheat and corn, boiled wheat and corn, flour made from the mesquite bean, beans, boiled squash, green and dried squash seeds, beef, and poultry.

Grain

The roving Papagos, those living off the reservation, raise only grain enough, principally wheat and corn, for their own use. Squashes, melons, and sugar cane make up the list of their common crops. Cultivation with them consists in scratching the ground with their stick plows and planting the seed. They pay no attention whatever to weeds. They enclose small fields of fertile ground in the mesas with brush fences and then plant after a rain at the right season. If it rains in November, they plant wheat. Rain in December will insure a good growth of straw, but rain in February will be necessary to mature the berry. The failure of rain in any of the 3 months will prevent planting or about ruin the crop which has been started. Owing to the uncertainty of propitious rains they obtain crops, apart from irrigation, only about once in 6 years.

Their wheat is white, a short, plump berry, of remarkably good quality. In the off years they resort to the reservation, raise a little grain, and “pack” it to their villages. Corn, squashes, sugar cane, and melons are raised after the summer rains.

They grind grain on an inclined stone, called a metáte, using a smaller stone, about the size of a brick, called a mamo, as the crushing power. A handful of whole grain is placed at the top of the metáte, a part of it is scattered over the surface of the stone with a dexterous flirt of the hand, and it is then powdered by two or three energetic rubs with the small stone. The whole process resembles that of washing clothes with a washboard. The flour is caught in a bowl as it falls from the metáte, is clean and free from grit, and contains all the nutriment of the grain.

Parched wheat, when ground in this manner, is mixed with water, forming a palatable drink, called peuole. Corn is never ground raw, but after it has been boiled, and the meal is pressed and rolled up in soft corn husks and forms their bread for journeys. It is superior in taste, in my judgment, to any kind of corn bread made by the whites. They manufacture a kind of cheese from milk, but have no process for butter making.

Stock

The Papagos have small herds of stock and droves of horses. These constitute their substance, but such possessions can not be large in view of the uncertainty of water. Nearly every family has a few fowls. Their wants are few, and those are easily satisfied. They are self-supporting, and no charge on the government for either food or clothing.

An occasional farm wagon was found in a village, but in Kaki-wah there were 4. This village is about 90 miles from Tucson and 10 from the Mexican line.

Game

Various species of deer abound, and in season the markets of the whites are supplied with venison by the Indians. Mountain sheep and goats are also brought in by them, but in less numbers than deer. Black and cinnamon bears are occasionally killed. The cottontail rabbit abounds, and is in demand for the table. The flesh is white, and fully equal to chicken in delicacy of flavor. Dangerous wild animals are also killed by the Indians in considerable numbers. The most formidable of these is the mountain lion. This animal destroys young stock, and is therefore hunted with zeal by the Papagos. The pelts possess a trifling value. The wildcat and civet cat are very numerous. The coyote, fox, jackrabbit, and skunk make up a group of animals which are pests, though not dangerous ones. The jackrabbit is sometimes used for food.

Birds

Among the birds useful to Indians are the quail, dove, mocking bird, and cardinal bird. These are trapped with great success by them, the quail and dove for food, the others for household pets, their sale forming quite an income. Hawks, owls, and crows abound. Wild ducks, geese, bittern, heron, and snipe are killed in their migration back and forth between Mexico and California. It will be seen that the Indians have many food resources on wing and foot, valuable for consumption or sale.

Dwellings

No tents are used among the Papagos, and about two-thirds of the houses are made of adobe, the rest being constructed of mud and brush. They consist of but one room, and have dirt roofs laid on rafters of small trees. There is no uniformity as to the size of the houses. The adobe bricks are made in an open frame of four compartments from a gray mud or clay mixed with short cut straw or hay. This mold is placed upon the ground, filled with the soft adobe, packed firmly, and then the frame or mold is removed and the brick left to dry. The usual size of a brick is 4 by 9 by 18 inches.

The Papagos are cleanly in their habits. They sweep the dirt floors of their houses and in some cases the ground around them. No vermin of any kind was found in any of their houses.

Papago Customs

Clothing

The men wear boots or shoes, pants and shirts, and straw or felt hats. A canvas jacket is worn on cool days or on a journey. The women wear shoes, stockings, and skirt and waist. Blankets are quite common with both sexes, with the women serving as shawl and head covering. The women sew nicely by hand, using thimbles. They also use sewing machines, of which there were three in Ki-ki-wah.

Morals

The men were generally represented to me to be truthful and honest and the women to be virtuous. Prostitution is said to be unknown among them. This may be due to the fact, as some claim, that wives are taken and abandoned at will. Occasionally a man was found with 2 wives.

Their honesty was tested in various ways on our trip. The outfit of 2 wagons was left unguarded for a whole day when we made the trip from Tecolote to Fresnal and neighboring villages, and not a thing was disturbed. Twice after we left villages, forgotten articles were brought to us by men on horseback. These articles would not have been missed, and might have been kept by them with perfect impunity. The Papagos are not addicted to intoxicating drink, but smoking and gambling are so common among them that they will even stake their clothing on races, either by men or horses, and on the simple games with which they are familiar.

Religion

The Papagos are nominally Catholics. Adults and children wear crosses and charms. They believe in witches and evil spirits, and buy charms to insure good luck.

At the little village of Ki-ki-wah, where there are a number of returned scholars, it was said that a simple service was held by these “graduates,” in which they explained on Sundays the things they had learned about the white man’s religion. At the village called Gunsight, 2 Mormons have been living among the Indians for nearly 2 years.

Education

The Papago youth of both sexes show considerable capacity for mental culture. Many of the Papagos speak Spanish fluently, even after having been at school for 2 or 3 years. When at home on their vacations they only hear Papago and Spanish, which tends to the disuse of what English they have acquired. They are docile, mild in disposition, and well inclined toward their teachers. They learn slowly but surely. The chief difficulty of receiving any permanent benefit from educating them is that they are so disastrously affected by the conditions which meet them when they return to their homes. They virtually return to barbarism and all old influences of a nonprogressive character.

The boys readily learn improved methods of agriculture, also the trades of tinsmith, blacksmith, and carpenter, while the girls learn sewing, cooking, and the general duties of housekeeping.

School Attendance

During the 3 years of the Tucson Presbyterian mission school, 73 Papago children have been enrolled. There are 50 now on the rolls. The number enrolled at the San Xavier reservation schools is about 20. At Sacaton there are 15 Papagos on the roll. The government school there is well conducted.

It will be seen that in the district visited, with the addition of the Papago scholars at San Xavier, not more than 100 in all of these children are in school. The total number of Papago children of school age is probably about 2,000. Their parents will exercise no authority to secure their attendance at school even when they wish them to go, nor, on the other hand, do they hinder them if they desire an education.

Pathological

The Papagos are very liable to consumption and pneumonia. This arises from the exposure to which they are subject in inclement weather, as all mud roofs leak in protracted rains and a pitch sufficient to carry off the rain would cause the adobe itself to wash off entirely. Many of the tribe are pitted badly with smallpox. Children are subject to measles and whooping cough in addition to lung difficulties. The Papagos have no medical treatment whatever among themselves, and in case of sickness resort to the “medicine man” with his mumments.

The Indians seem to be able to deal with flesh injuries, but are powerless in cases of disease or fractures of bones. In acute local pain, they sometimes put a pinch of cotton on the flesh and burn it there, repeating the process on a new spot at a little distance. Ordinarily their only resource is stoical submission.