The Omaha, so far as known, formerly dwelt in villages composed of dwellings made of sod and timber. The illustration gives the outward appearance of these dwellings, which are built by setting carefully selected and prepared posts closely together in a circle and binding them firmly with willows, then backing them with dried grass and covering the entire structure with closely packed sods. The roof is made in the same manner, having an additional support of an inner circle of posts, with crotches to hold the cross logs which act as beams to the dome-shaped roof. A circular opening in the centre serves as a chimney and also to give light to the interior of the dwelling; as seen in the picture, a sort of sail, is rigged and fastened outside of this opening to guide the smoke and prevent it from annoying the inmates of the lodge. The entrance passage way usually faces the east, is from 6 to 10 feet long, and is built in the same manner as the lodge. A skin or blanket is hung at the outer opening, and another at the inner entrance, thus affording a double protection against wind and cold. The fire is kindled in a hollowed place in the centre of the floor, and around the wall are arranged platforms made of reeds, on which robes are spread for use as seats by day and as beds by night.

These couches are often fitted with an upright framework, on which skins or blankets are hung to be dropped as curtains, thus giving privacy to the occupants. Two, three, or four families can easily live in one of these spacious sod dwellings, and the writer has frequently seen from 200 to 500 guests entertained therein, on the occasion of a ceremonial.

The work of building these dwellings is shared by men and women; to the former belongs the duty of adjusting the roof about the central opening. From 50 to 100 of these structures would be grouped together in the village, the site of which was always near a running stream, convenient timber, and, generally, surrounded with hills, from which lookouts could dive notice of the approach of enemies.

Corn, beans, pumpkins, and melons were raised in large quantities. The corn and beans were dried and stored in caches built outside the lodges, and the pumpkins were cut as an apple is peeled and hung up in festoons to dry and then kept for winter use. The sheltered valleys and bottom lands were favorite spots for cultivation, the same family often using the same piece of land for years. Occupancy was always respected. The agricultural work was chiefly done by women, although the men were ready to assist when their help was needed. All work and property was individual; nothing was raised in common or held as a tribal product. Relations helped one another in harvesting, but this custom was not obligatory.

For meat and the material for clothing, implements, &c., the Omaha depended upon game. Hunting, however, was never a mere pastime, but an arduous duty, regulated by tribal ceremonies and officered by men appointed with due form and under serious obligations. The annual hunt occurred during the summer months, on which occasion all the tribe took part, except the infirm and sick, who were left in the village under the charge of warriors who served as a guard in the absence of the tribe.

The picture show how the tents and tent poles were carried with four poles to a pony, led by the women, – from 3 to 6 ponies were required to transport a tent-and how the tent poles and tents were arranged. When on the hunt the tribe moved and camped in the order of their bands or genies. The Omaha, in common with most of the Indian tribes, arc divided into bands or genies. Each band or gens has a distinct name, mythical origin, sacred symbols, and a fixed place in the tribal circle. There are ten gentes in the Omaha tribe. No. 7 of the Exhibit gives a bird’s-eye view of the tribal circle: The opening was to the east; five gentes camp on the south half of the circle and form the Hun-ga-chey-nu side of the tribe, and five gentes camp on the north side of the circle and form the In-sta-sun-da side of the tribe. The three sacred tents are upon the south, or Hun-ga-chey-nu side. The sacred tent just south of the opening is that dedicated to war ceremonies and is in charge of the We-jin-ste gens; from this pens some of the most notable head chiefs of the tribe have arisen. The two sacred tents in the middle of the south half are dedicated to, the sustaining of life, and are in the care of the Hun-ga gets. This gens, as its name suggests-the ancient one, or leader occupies an important position and has charge of the principal ceremonies of the tribe. Other gentes are intrusted with tribal duties, and, in certain gentes, particular families have the custody of the sacred articles used at religious festivals.

The names of the gentes are as follows; the figures refer to those below upon the groups of tents on the illustration:

In-sta-sun-da side of tribal circle. North half.

- In-sta-sun-da.

- In-gri-zhe-da.

- Ta-pa.

- Tae-sin-da.

- Ma-thin-ka-ga-he. Hun-ga-chey-nu side of tribal circle.

South half.

- Kan-se

- Tha-ta-da

- Hun-ga

- In-kae-sab-ba.

- Wae-jin-ste.

- Sacred tent of war ceremonies, under charge of the Wae-jin-ste gens.

- Two sacred tents dedicated to the sustaining of life, containing sacred pole and sacred white buffalo cow’s hide, in charge of the Hun-ga gens.

A full explanation of the social organization of the tribe, together with the duties and functions of the various gentes, would transcend the limits of this paper.

On the homeward journey front the annual hunt, when the tribe was within four days’ march of the village, they halted, and the great ceremony of thanksgiving for safety, food, and clothing took place, lasting four days. When this was over, the people scattered and made haste to reach their homes. Each family, on arriving at its dwelling, then held the private ceremony of thanksgiving, a similar festival to that which takes place upon the completion of the building and marks the consecration of the lodge.

The annual hunt and its attendant ceremonies have been abandoned since 1878, but the organization of the tribe by gentes is not affected by this change.

The Omaha have been fortunate in their head chiefs during the present century. Um-pa-tun-ga recognized at an early date the advantages of civilization, and, as far as his ability served, he used his influence to prepare his people for the coming change. As a consequence of this policy, in 1836, when, with other tribes, the Omaha joined in a treaty extinguishing any title they might have claimed to lands lying east of the Missouri River, their share of the compensation received from the United States was taken in agricultural implements and the services of a resident blacksmith.

In the twenty years which followed, the westward rush of emigration brought much suffering to the border tribes, particularly to those who were trying to take on civilized life. The stream of white settlers pushed through the. Indian lands, destroying their fields of corn, beans, &c., and mercilessly killing off the game, thus imperiling the Indians’ entire supply of food. At the same time, these tribes became objects of distrust, being regarded as faithless to ancient tradition, and consequently they were assailed by those Indian tribes who were determined to resist innovations in imitation of the white people.

In 1845 the Indian Commissioner reported to the Secretary of War: ” The Omaha are a peaceable people and have ever been the friends of the whites. From their exposed position and poverty, not being able to procure fire-arms, they are rapidly being reduced by the frequent attacks of war parties.”

The double fire of Indian enemies and the depredations of emigrants brought much suffering to the Omaha, which was endured with an heroic patience. Determined to abide in the land of their fathers, resisting all pressure and offers to go to the Indian Territory, the tribe decided, in 1855, to sell their vast hunting lands and reserve the site of their ancient home on the banks of the Missouri and meet there as best they could the problem of their future.

At this time the Omaha made their first separate treaty with the United States, and ceded the territory lying between the Niobrara on the north and the Platte on the south, some two hundred miles west from the Missouri River.

The Indian Commissioner in 1861 states: ” Much of the progress observable in the condition of this tribe is attributable to their intelligent and exemplary chief, La Flesche ” (the adopted son and successor of Um-pa-tun-ga), ” and to the excellent school in their midst.”

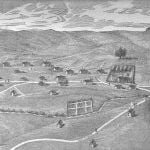

No. 8 in the Exhibit is a drawing of the reservation as it appeared in 1862, about six years after the people, had left Bellevue, a few miles south of Omaha City, whither, in 1848, they had fled for safety and protection.

The bulk of the tribe, according to their ancient fashion, at once built a village of sod dwellings between the two Black-bird creeks. A few mixed bloods took up separate homes and opened animal farms, while on the military road, the only road through the country at that time, the agency was established and a government farm begun. A number of the more progressive men followed the lead of La Flesche and erected a village of frame and log houses not far from the mission school, the mill and shops, and the steamboat landing. The illustration (No. 9 of the Exhibit) is taken from a sketch of this village drawn from memory by one of the Indians who lived there.

- Um-pa’s house.

- The-me-ka-the’s house.

- Wa-tha-bas-zin-ga’s house.

- Me-ha-ta’s house.

- Bron-tee’s house.

- Um-pa-spa’s house.

- Joseph La Falsetto’s house.

- Wa-na-shae-zin-ga’s house.

- Tae-on-ka-ha’s house.

- Ca-hae-num-ba’s house.

- Num-ba-tae-wa-thae’s house.

- Ta-hae-zin-gae’s house.

- Ne-ma-ha’s house. I. 14. Du-ba-mon-ne’s house.

- Wa-jae-pa’s house.

- Wa-zin-ga’s house.

- Ne-ou-ga-shu-dae’s house.

- Wa-ne-ta-wa-ha’s house.

- Ma-he-nin-ga’s house.

- Sin-dae-ha-ha’s house

- Wa-ha-nin-gae’s house.

- Ma-wa-da-ne’s house.

- Grae-dun-nuz-ze’s house.

- Bridge over stream.

- Vegetable garden, La Flesche’s.

Now. 12 and 13 are sod houses. and No. 7 and 23 are frame houses. The four structures not numbered are barns. All the material used to build these houses was furnished by the Indians themselves. They cut the logs and hauled them to the saw-mill to have them sawn into thick planks and flooring. The shingles they bought themselves. Each man chose his own place to put his house on. The planks were of oak and the flooring of cottonwood. The bridge was built by the Indians, and the material was also furnished by them.

One hundred and sixty acres or more on the river bottom land were fenced off, ploughed, and divided, so that each family had a field of its own. La Flesche and a few others started separate farms a little removed from the village. The men raised large, crops of corn, hauling it in winter on the ice to Sioux City and selling it at a good price. Sorghum was another product, and here the first wheat was planted. The children of these families were all in the mission school and some were learning trades in the shops.

In the midst of this labor and prosperity of the people in their new life they cared little for the derisive name of “the make-believe white men,” given them by the conservative Indians.

In the treaty of 1855-56 the chiefs had stipulated for the survey and apportioning of the land to individuals, and they never ceased to urge upon the Government the fulfillment of this agreement. In 1865 (Treaty of March 6, 1865), when the Omaha sold a strip off the northern part of their reservation as a home for the distressed Winnebago, the partition of the land in severalty was again agreed upon, and after five years more of waiting and struggle the country was surveyed and over 200 allotments were made to the Indians. The certificates issued were supposed to be patents, and eight years later the disappointment and anxiety which followed upon a knowledge of the inadequate legal character of the papers tendered to cripple the ambition and abate the courage of the farmers, who had scattered from their village, taking down their little houses and putting them up upon their allotments. Meanwhile the old village of sod dwellings had been broken up and the example of the progressive men, together with the influence of agents and missionaries, made itself felt throughout the entire tribe. Wagons, harness, and agricultural implements had been purchased with the annuity money (rations were not issued), and a large, portion of the tribe were working in ploughed fields.

Many were the prayers offered up by the Christian Indians that the land so dear to them might be spared to them and their children. Urgent appeals were made to Congress, while subtle influences were brought to bear on some of the non-progressive Indians to urge a movement of the tribe to the Indian Territory. After a time of sorrowful waiting help came unexpectedly through a student, who had gone among the Omaha solely for ethnological study; and, when the story of the work of the people upon their farms became known, Congress passed a bill giving the Omaha titles to their lands in severalty. In Jane, 1884, the work of allotment was completed, and nearly 76,000 acres are now owned individually by 1,179 persons: 160 acres by each head of .a family, 80 acres by each orphan and single person over 18 years, and 40 acres by each person under 18 years of age, the United States holding the patent in trust for 25 years.

The Omaha have about 8,000 acres under cultivation, and raise large crops of corn, wheat, and other small grains, potatoes, and vegetables. The picture (No. 10 of the Exhibit) is of a farmer on his way to the mill with a load of corn. The crops are mainly sold in the towns on the southern border of the reservation: Bancroft, Lyons, Oakland, and Decatur. The result of Omaha farming for the year 1884 amounts to 100,000 bushels of corn, 50,000 bushels of wheat, 30,000 bushels of vegetables, and over 30,000 tons of hay put up. All this represents the labor of individual farmers, working on farms from 3 acres to 100 in acres in extent, and without any outside help, for there is not a hired farm laborer on the reservation.

The illustration tells the store of one man’s effort, and his is not an exceptional case. The owner of this farm and buildings began to work about ten years ago, with but one lame pony as an assistant. He secured the breaking of a few acres and the Government issued him a wagon and a set of harness. By diligence and hard work his crops and his farm have increased, until today he has nearly fifty acres under cultivation. A field ready for next spring’s planting is seen to the left; other fields lie beyond the line of the photograph. His wheat and corn bins are on the hill, and the little log cabin in the centre, with a dirt roof, was his first house; it now serves as his kitchen. The frame house, painted grey, with brown trimmings, was built one year ago. Just back of this house is a fruit-bearing orchard. He has bought farming machines with his own earnings, but these are under cover of the shed, to the left. He refused to bring them out when the picture was taken, as the day was threatening, and suggested that people could be told why these proofs of industry were not visible. Here is represented the unaided labor of one man who, ten years ago, had not an acre under cultivation. His children are all in school and he and his wife are earnest Christians.

The accompanying Omaha Reservation Maps shows the land as now owned by individuals, and indicates the great change which has taken place in twenty years. It will be noticed that the Indians do not avoid, but court contact with their white neighbors. Trade and education are making the interests of both peoples identical.

As early as 1846 the Presbyterian Board undertook the establishment of a mission school for the benefit of the Omaha and Otoe. When the Omaha tribe moved upon their present reservation, in 1856, a commodious mission building was erected for the reservation. The house is still standing and doing excellent service among the people. At this mission many noble men and women have labored, among them Rev. Mr. Burtt, who, for many years, did a work which bears ample fruit to the present day. The young men and women who were boys and girls under his care are now all working on farms or at trades, speaking English, bringing up their children under Christian instruction, and thus helping for ward their entire people. For a time the mission boarding school was closed, while the experiment of day schools, scattered over the reservation, was tried. These were abandoned after a few years, and about five years ago the mission boarding school was reopened. No. 16 of the Exhibit is a photograph of the mission corps of teachers and helpers and the little girls now under their care. The mission school has always received Government aid in the maintenance of the children under its charge, the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions supporting the missionary, teachers, helpers, and making up the deficiency of funds.

In 1879 the agencies for the Omaha and Winnebago were consolidated and the Government opened an industrial boarding school in a building that a few years before had been erected as an infirmary, which proved a failure, the Indians being unwilling to part with their old and sick. The illustration shows the school and its seventy scholars, all doing well. This same year the grist and saw mill and shops were taken down from their position on the river bottom and removed to the agency, some three miles inland. The Missouri River had already carried away the bottom lands where the ” make-believe white men” had farmed. It was also in this year that Indian apprentices were made employees at the Government blacksmith and carpenter shops. During the past year, 1884, at the request of the tribe, these shops have been closed as tribal institutions and opened under individual enterprise; the people paying for the work done for them. In the picture at the top of the page is seen one of the Indian carpenters at work in his shop.

During the thirty years the Omaha have been upon their reservation they have had 13 agents, some of whom have been able, careful, and conscientious men, who have labored earnestly for the upbuilding of the people, and these well directed efforts have produced an enduring effect which other less favorable administrations were not able to fully overthrow. The problems which beset Indian agents are

many and difficult, and demand first rate ability-,’to attack and master, for these problems do not pertain exclusively to the Indians, but include the white settlers as well, and also involve the difficult matter of adjusting heedless political interference.

The earnest missionary labor, not only that which comes directly under the church, but that which is often given by Christian agents and employes and their families, has borne good fruit among the Omaha and this rich harvest is in a. great measure due to the responsive influence of some of the leading Indian men, who accepted Christianity as the standard of life and labored to lead their people toward the path of industry and morality. It was largely the result of the energetic rule of Head Chief La Flesche and his corps of soldiers or police, that twenty years ago intemperance was so severely punished that no man dared to risk the terrible flogging given the drunkard. So effectual was the work done that to-day, although a new generation has arisen, there is almost no drunkenness among the Omaha.

The Mission Church numbers nearly 100 communicants. The influence of these Christian men and women has leavened the tribe, and today it would be difficult to find a community more peaceful and industrious. Of coarse allowance must be made for poverty of mind and estate, as but few of the Indians have anything more than the most elementary education, and the people, being entirely self-supporting, have not yet been able to accumulate capital.

Over seventy of the Omaha youth are at schools outside of the reservation: at the Government Industrial School at Genoa, Nebraska, under the superintendency of Col. Tappan; at a similar school at Houghton, Lee county, Iowa, under the care of Benj. Miles; at Lincoln Institute, Philadelphia, Pa.; at Carlisle Training School, Carlisle, Pa., under the wise pioneer of Indian training schools, Capt. R. H. Pratt. Several of the boys and girls sent to this school are at present living in the families of farmers, earning their board and clothes, working and going to the district schools with white children, and finding friends and respect in their new relations. Other Omaha are at Hampton, where General Armstrong has charge, and among these are several married couples, who are there together gaining a wider knowledge through books and a daily experience of civilized life that is beyond price.

Cottages have been erected by the gift of two ladies interested in this new feature of Indian education, and here the young people live, becoming accustomed to the refinements of life, and it is hoped that money will be secured to furnish the material to build similar houses upon their farms when they return home this summer. The men will do the mechanical work, being trained carpenters, and from their crops pay a yearly rental, which will be applied to the purchase of their houses. Thus two ends will be secured: (1) The young men will have earned their homes; their independence will be unharmed. (2) The money will gradually roll back, to be expended a second time in the same good service. The illustration is of one of these cottages; the wife and mother sits at the window of her pretty home, while little Eddie, her child, a bright boy about four years old, looks out upon us, wearing the golden “Star,” the prize badge for speaking “only English.”

The Omaha Indians, for the sake of clearness, have been taken for this exhibit, as a picture to show ford what has been actually accomplished in bringing a people from barbarism to civilized life, and thus to demonstrate that civilization is no fanciful theory, but, under proper care and influences, is within the grasp of all the Indians. From this sketch of the Omaha tribe we see that, while many persons are still questioning whether the Indian will work, whether he can be educated, whether it is possible for him to become self sustaining, these questions have been answered in the affirmative by facts; for here is a tribe which works, is educated, and is self sustaining, having, within twenty-five years, passed from Indian modes of life to farming upon their lands in severalty, independent of Government support.

It should be added that there are many other tribes ready to give a like testimony.