The Ojibway (the Sauteux of many writers) formed the connecting link between the tribes living east of the Mississippi and those whose homes were across the ” Great River.” A century ago their lands extended from the shores of Lake Superior westward, beyond the headwaters of the Mississippi to the vicinity of the Turtle Mountains, in the present State of North Dakota. Thus they claimed the magnificent lakes of northern and central Minnesota, Mille Lac, Leech Lake, Cass Lake, and Red Lake, on the shores of which stood, many of their camps and villages, serving as barriers against invasions and attacks by their inveterate enemies, the Sioux. The Ojibway are essentially a timber people, whose manners and customs were formed and governed by the environment of lakes and streams, and who were ever surrounded by the vast virgin forests of pine. While game, fish, and wild fowl were abundant and easily obtained, yet during the long winters when the lakes were frozen and the land was covered by several feet of snow there were periods of want when food was scarce.

The habitations and other structures of the Ojibway, which have already been described and figured 1 , were of various forms, constructed of several materials, and varying in different localities, according to the nature of the available supply of barks or rushes.

In the north, on the shores of Lake Superior and westward along the lakes and streams, as in the valley of Red River and the adjacent region, the majority of structures were covered with sheets of birch bark, secured to frames of small saplings.

About the year 1804 Peter Grant, a member of the old North-West Company, and for a long period at the head of the Red River Department of the company, prepared an account of the Sauteux Indians, and when describing the habitations of the people, wrote ” Their tents are constructed with slender long poles, erected in the form of a cone and covered with the rind of the birch tree. The general diameter of the base is about fifteen feet, the fire place exactly in the middle, and the remainder of the area, with the exception of a small place for the hearth, is carefully covered with the branches of the pine or cedar tree, over which some bear skins and old blankets are spread, for sitting and sleeping. A small aperture is left in which a bear skin is hung in lieu of a door, and a space is left open at the top, which answers the purpose of window and chimney. In stormy weather the smoke would be intolerable, but this inconvenience is easily removed by contracting or shifting the aperture at top according to the point from which the wind blows. It is impossible to walk, or even to stand upright, in their miserable habitations, except directly around the fire place. The men sit generally with their legs stretched before them, but the women have theirs folded backwards, inclined a little to the left side, and can comfortably remain the whole day in those attitudes, when the weather is too bad for remaining out of doors. In fine weather they are very fond of basking in the sun.

“When the family is very large, or when several families live together, the dimensions of their tents are, of course, in proportion and of different forms. Some of these spacious habitations resemble the roof of a barn, with small openings at each end for doors, and the whole length of the ridge is left uncovered at top for the smoke and light.” 2 And referring briefly to the ways of life of the people:” In the spring, when the hunting season is over, they generally assemble in small villages, either at the trader’s establishment, or in places where fish or wild fowl abound; sturgeon and white fish are most common, thought they have abundance of pike, trout, suckers, and pickerel. They sometimes have the precaution to preserve some for the summer consumption, this is done by opening and cleaning the fish and then carefully drying it in the smoke or sun, after which it is tied up very tight in large parcels, wrapped up in bark and kept for use; their meat, in summer, is cured in the same manner. .. Their meat is either boiled in a kettle, or roasted by means of a sharp stick, fixed in the ground at a convenient distance from the fire, and on which the meat is fixed and turned occasionally towards the fire, until the whole is thoroughly done; their fish is dressed in the same manner.” 3

The method of cooking food, as mentioned in the preceding paragraph, is graphically illustrated in the old sketch made a century ago, now reproduced in plate 6a. This shows a family gathered about a small fire where food is being prepared. and beyond is a bark-covered wigwam. The sketch bears the legend, ” A. family from the tribe of the wild Sautaux Indians on the Red River. Drawn from nature.” It indicates the primitive dress and appearance of the people, and it is of interest to compare this with the photograph which is reproduced in plate 6b, showing another small group of the people three-quarters of a century later. Such were the changes within that period.

Similar to the preceding were the habitations shown by Kane in a sketch made during the early summer of 1845, the original painting being reproduced as plate 7a. This was described as ” an Indian encampment amongst the islands of Lake Huron; the wigwams are made of birch-bark, stripped from the trees in large pieces and sewed together with long fibrous roots; when the birch tree cannot be conveniently had, they weave rushes into mats … for covering, which are stretched round in the same manner as the bark, upon eight or ten poles tied together at the top, and stuck in the ground at the required circle of the tent, a hole being left at the top to permit the smoke to go out. The fire is made in the centre of the lodge, and the inmates sleep all round with their feet towards it.” 4 The interesting painting could well have been made among the Ojibway camps or settlements of northern Minnesota instead of representing a group of wigwams located many miles eastward, but this tends to prove the similarity of the small villages in the region where large sheets of birch bark were to be obtained.

Between the loosely placed sheets of bark were necessarily many openings through which the wind could enter, and in addition was the open space at the top intentionally left as a vent through which the smoke Could escape from the inside. In describing the appearance of the interior of such a structure it was told how:

“Around the fire in the centre, and at a distance of perhaps 2 feet from it, are placed sticks as large as one’s arm, in a square form, guarding the fire; and it is a matter of etiquette not to put one’s feet nearer the fire than that boundary. One or more pots or kettles are hung over the fire on the crotch of a sapling. In the sides of the wigwam are stowed all clothing, food, cooking utensils, and other property of the family.” When referring to the great feeling of relief on arriving at such a shelter in the frozen wilderness the same, writer continued:

“When one has been traveling all day through the virgin forest, in a temperature far below zero, and has not seen a house nor a human being and knows not where or how he is to pass the night, it is the most comforting sight in the whole world to see the glowing column of light from the top of the wigwam of some wandering family out hunting, and to look in and see that happy group bathed in the light and warmth of the life-giving fire, and no one, Ojibway or white, is ever refused admission; on the contrary, they are made heartily welcome, as long as there is an inch of space.” 5 As a missionary among the Ojibway of northern Minnesota for a quarter of a century, Dr. Gilfillan learned to know and love the forests and lakes in the changing seasons of the year. and to know the ways of life of the Ojibway as few have ever known them.

The structures just mentioned were of a circular form, with the ends of the poles which supported the bark describing a circle on the ground. Of quite similar construction were the larger oval wigwams, where two groups of poles were arranged at the ends in the form of semicircles, with a ridgepole extending between the tops of the two groups. Other poles rested against the ridgepole and so formed the sloping supports upon which the strips of bark were placed. One most interesting example of this form of primitive habitation was visited by the writer during the month of October, 1899. It formed one of a small group of wigwams which at that time stood near the Canadian boundary, north of Ely, Minnesota. It was about 18 feet in length and between 8 and 9 feet in width. There were two entrances, one at each end, with hanging blankets to cover the openings. Within, along the median line on the ground, burned four small fires. Beautiful examples of rush mats, made by the women, were spread upon the ground near the sloping walls, these serving as seats during the day and sleeping places at night. Many articles hung from the poles, which sustained the bark covering, as small bags and baskets, and mane bunches of herbs. In one corner was a large covered mokak, and on the opposite side was a carefully wrapped drum, owned by the old Ojibway, Ahgishkemunsit, the Kingfisher, who was sitting on the ground near by.

Quite similar to the preceding must have been the wigwam visited by Hind in 1858. This stood a short distance from Manitobah House, of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and belonged to an Ojibway hunter. As Hind wrote: “His birch-bark tent was roomy and clean. Thirteen persons including children squatted round the fire in the centre. On the floor some excellent matting was laid upon spruce boughs for the strangers; the squaws squatted on the bare ground, the father of the family on an old buffalo robe. Attached to the poles of the tent were a gun, bows and arrows, a spear, and some mink skins. Suspended on cross pieces over the fire were fishing nets and floats, clothes, and a bunch of the bearberry to mix with tobacco for the manufacture of kinni-kinnik.” 6

Hind was accompanied on his second journey, in 1858, by a photographer, Humphrey Lloyd Hime, who made many interesting negatives while in the Indian country. Among the photographs made at this time are three views of bark wigwams of the Ojibway which stood near the banks of Red River. These are now reproduced in plates 7b, and 8a, b.

While in the vicinity of Red River the year before (1857) Hind encountered several interesting Ojibway structures. At a point not far north of the Minnesota boundary his party crossed the Roseau a few miles east of Red River, and there “on the bank at the crossing place the skeletons of Indian wigwams and sweating-houses were grouped in a prominent position, just above a fishing weir where the Ojibway of this region take large quantities of fish in the spring.

The framework of a large medicine wigwam measured twenty-five feet in length by fifteen in breadth; the sweating-houses were large enough to hold one man in a sitting position, and differed in no respect from those frequently seen on the canoe route between Lakes Superior and Winnipeg, and which have been often described by travelers. 7 During the journey, when camping on an island in Bonnet Lake, the party encountered “an Indian cache elevated on a stage in the centre of the island. The stage was about seven feet above the ground, and nine feet long by four broad. It was covered with birch bark, and the treasures it held consisted of rabbit-skin robes, rolls of birch bark, a, ragged blanket, leather leggings, and other articles of winter apparel, probably the greater part of the worldly wealth of an Indian family.”

The canoe route between the lakes mentioned by Hind was often broken by dangerous rapids, around which it was necessary to carry the canoes, as Catlin described the Ojibway party doing at the Falls of St. Anthony.

The ceremonial lodge, of the Ojibway, where the Mĭdé rites were enacted, was often 100 feet or more in length and about 12 feet in width. The frame was made of small saplings, bent and fastened by cords, similar to the frames of wigwams which were to be covered with mats or sheets of bark, but the coverings of the ceremonial lodges were usually of a more temporary nature, boughs and branches of the pine and spruce being sometimes used, which would soon fall away, although the rigid frame would stand from year to year, to be covered when required.

Somewhat of this form was the “medicine lodge,” described by Kane. This stood in the center of a large camp of the “Saulteaux” or Ojibway, not far from Fort Alexander, which was about 3 miles above Lake Winnipeg, on the bank of Winnipeg River. The camp was visited June 11, 1846, and in referring to the lodge:” It was rather an oblong structure, composed of poles bent in the form of an arch, and both ends forced into the ground, so as to form, when completed, a long arched chamber, protected from the weather by a covering of birch bark. On my first entrance into the medicine lodge, I found four men, who appeared to be chiefs, sitting upon mats spread upon the ground gesticulating with great violence, and keeping time to the beating of a drum. Something, apparently of a sacred nature was covered up in the centre of the group, which I was not allowed to see. The interior of their lodge or sanctuary was hung round with mats constructed with rushes, to which were attached various offerings consisting principally of bits of red and blue cloth, calico, &c., strings of beads, scalps of enemies, and sundry other articles beyond my comprehension.” 8

It is quite evident the frame of the large lodge encountered by Hind was similar to the structure described by Kane a few years before. Both stood in the northern part of the Ojibway country, a region where birch bark was extensively used as covering for the wigwams, and where it was easily obtained.

The temporary, quickly raised shelters of the Ojibway were described by Tanner, who learned to make them from the people with whom he remained many years. Referring to a journey up the valley of the Assiniboin, he wrote: “In bad weather we used to make a little lodge, and cover it with three or four fresh buffalo hides, and these being soon frozen, made a strong shelter from wind and snow. In calm weather, we commonly encamped with no other covering than our blankets.” 9 On another occasion fire destroyed the wigwam and all the possessions of the family with whom he lived, and then, so he said: “We commenced to repair our loss, by building a small grass lodge, in which to shelter ourselves while we should prepare the pukkwi for a new wigwam. The women were very industrious in making these. At night, also, when it was too dark to hunt, Wa-Ine-gon-a-biew and myself assisted at this labor. In a few days our lodge was completed. 10 And again when near Rainy Lake, “I had no pukkwi, or mats, for a lodge and therefore had to build one of poles and long grass.” It is quite evident the shelters of poles and grass, as mentioned by Tanner, were similar to those erected by the Assiniboin as described on another page, and as indicated in the painting by Paul Kane, which is reproduced as plate 25a.

Two very interesting old photographs, made more than half a century ago, are shown in plate 9. One, a, represents clearly the elm-bark covering of the wigwams, and in this picture the arbor suggests a Siouan rather than an Ojibway encampment; b is more characteristic of the Ojibway.

The structures encountered in the Ojibway country farther south differed from those already mentioned, the majority of which were covered with sheets of birch bark, a form which must necessarily have been restricted to the northern country. But the type was widely scattered northward, and undoubtedly extended eastward to the Atlantic, especially down the valley of the St. Lawrence into, northern Maine and the neighboring Provinces. South of this zone were the dome-shaped mat or bark covered wigwams, varying in different localities according to the available supply of barks, or of rushes to be made into mats, which served to cover the rigid, oval-topped frame. Most interesting examples were standing in the Ojibway settlements on the shore of Mille Lac, Minnesota, during the spring of 1900. One, which may be accepted as a type specimen, was of a quadrilateral rather than oval outline of base, and measured about 14 feet each way, with a maximum height of 6 feet or more. The saplings which formed the frame were seldom more than 2 inches in diameter, one end being set firmly in the ground, the top being bent over and attached to similar pieces coming from the opposite side. Other small saplings or branches were tied firmly to these in a horizontal position about 2 feet apart, thus forming a rigid frame, over which was spread the covering of mats and sheets of bark, the latter serving as the roof. In this particular example the covering was held in place by cords which passed over the top and were attached to poles which hung horizontally about a foot above the ground. A second row of mats was fastened to the inside of the frame and others were spread on the ground near the walls. A small fire burned within near the center of the open space, although the cooking was often done outside, just beyond the single entrance.

Although the Ojibway were numerous, they had few large villages or settlements. They lived for the most part in small, scattered groups, and often moved from place to place. However, there were some long-occupied sites, as at Red Lake. Sandy Lake, on the shores of Leech Lake, where the Pillagers gathered, and the more recently occupied villages at Mille Lac, sites once covered by the settlements of the Mdewakanton. These villages, which should more properly be termed “gathering places,” at once suggest the various descriptions and accounts of the great village of the Illinois, which stood on the banks of the upper Illinois during the latter part of the seventeenth century and was many times visited by the French.

When the Ojibway and Sioux gathered at Fort Snelling, at the mouth of the Minnesota River, during the summer of 1835 in the endeavor to establish peace between the two tribes or groups, they were encamped on opposite sides of the fort. Catlin, who was there at the time, wrote of the temporary camp of the Ojibway: “their wigwam, made of birch bark, covering the frame work, which was of slight poles stuck in the ground, and bent over at the top, so as to give a roof like shape to the lodge, best calculated to ward off rain and winds.” 11 Unfortunately, the original painting of the camp does not exist in the great collection of Catlin paintings now belonging to the National Museum. Washington. In the catalogue of the collection printed in London, 1848, it appears as “334, Chippeway Village and Dog Feast at the Falls of St. Anthony; lodges build with birch-bark: Upper Mississippi.”

An outline drawing of the picture was given as plate 238 to illustrate the account quoted above, but how accurate either description or sketch may be is now quite difficult to determine. However, it is doubtful if the structures had flat ends, as indicated, and mats may have formed part of the covering. Catlin continued his narrative and told of the removal of the camp 12 : “After the business and amusements of this great Treaty between the Chippeways and Sioux were all over, the Chippeways struck their tents by taking them down and rolling up their bark coverings, which, with their bark canoes seen in the picture, turned up amongst their wigwams were carried to the water’s edge; and all things, being packed in, men, women, dogs, and all, were swiftly propelled by paddles to the Falls of St Anthony.” They reached “an eddy below the Falls, and as near as they could get by paddling.” Here the canoes were unloaded and the canoes and all else carried about one-half mile above the Falls, where they again embarked and continued on their way. It is interesting to contemplate this scene and to realize it was enacted within the limits of the present city of Minneapolis so short a time ago. A beautiful example of the light birch-bark canoe of the Ojibway is shown in plate 10a, and a photograph of two old Ojibway Indians with similar canoes is reproduced in plate 10b. The canoes indicated by Kane in his painting (pl. 7, a) were of this form probably the most graceful and easiest propelled craft ever devised.

The various structures in an Ojibway village do not appear to have been erected or placed with any degree of order. Certainly this is true of conditions in recent times, and whether any accepted or recognized plan was followed in the past is not known. The small wigwams formed an irregular group on the shore of a lake or the bank of a stream surrounded by the primeval forest.

In the month of May, 1900, a council house which had been erected by the Ojibway some years before stood on a high point of land in the midst of dense woods, about 1 mile north of the outlet of Mille Lac, the beginning of Rum River, and about 200 yards from the lake shore. It was oriented with its sides facing the cardinal points, about 20 feet square, with walls 6 feet in height and the peak of the roof twice that distance above the ground. The heavy frame was covered with large sheets of elm bark, which had evidently been renewed from time to time during the preceding years. No traces of seats remained and grass was again growing on the ground which had served as the floor. This was the scene of the treaty of October 5. 1889, between the Ojibway of Mille Lac and the United States Government. Within a short time this very interesting primitive structure had disappeared and two years later no trace of it remained. Whether this represented an ancient type of building could not be ascertained.

The Ojibway villages were supplied with the usual sweat houses, a small frame covered with blankets or other material, so often described. Resembling these were the shelters prepared for the use of certain old men who were believed to possess the power of telling of future events and happenings. Such a lodge was seen standing on the shore of Lake Superior, about 18 mile from Fond du Lac, July 27, 1826. As described by McKenney: “this place, Burnt river is a place of divination, the seat of a jongleux’s incantations. It is a circle, made of eight poles, twelve feet high, and crossing at the top, which being covered in with mats, or bark, he enters, and foretells future events.” 13 Interesting, indeed, are the many accounts of the predictions believed to have been made by these old men.

A remarkable performance of this nature was witnessed by Paul Kane. When returning from the far West during the summer of 1848 the small party of which he was one arrived at Lake Winnipeg and on July 28 had advanced about midway down the eastern shore. On that day Kane made this entry in his journal: “July 28th.About 2 o’clock P. M., we endeavored to proceed, but got only as far as the Dog’s Head, the wind being so strong and unfavorable, woods, where they were holding their midnight orgies, and lay down amongst those on the outside of the medicine lodge, to witness the proceedings. I had no sooner done so than the incantations at once ceased, and the performer exclaimed that a white man was present. How he ascertained this fact I am at a loss to surmise. The Major, [M’Kenzie], with many other intelligent persons, is a firm believer in their medicine.” 14

In addition to the several forms of structures erected by the Ojibway, as already described, they reared the elm-bark lodge which resembled in form the log cabin of the early settlers. Three of these were standing on the south shore of Mille Lac, Minnesota, during the spring of 1900, and the outside of one, showing the manner in which the bark covering was placed, is indicated in plate 11b. This was similar in shape to the Sauk and Fox habitation reproduced in plate 19, although the Ojibway structure was more skillfully constructed. Habitations of a like nature were found among the Sioux villages on the banks of the Mississippi in the vicinity of Fort Snelling, and. others were erected within a generation by the Menomini in northern Wisconsin, but whether this may be considered a primitive form of structure has not been determined.

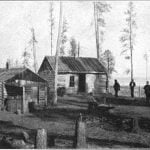

A trader’s store standing near the Ojibway village on the shore of Cass Lake, Minnesota, during the late autumn of 1899 is shown in plate 11a. Similar cabins were occupied by some of the Indian families, these having taken the place of the native wigwams.

Various objects of primitive forms, made and used by the Ojibway within a generation, are shown in plates 12 and 13.

Citations:

- Bushnell, D. I. Jr., Ojibway Habitations and other Structures. In Report of the Smithsonian Institution for the year ending June 30, 1917. Washington, 1919.[

]

- Grant, Peter; The Sauteux Indians. In Masson, pp. 329-330.[

]

- Ibid, pp. 330-331.[

]

- Kane, Paul, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America. London, 1859. pp. 6-7.[

]

- Gilfillan, J. A., The Ojibways in Minnesota. In Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. IX. St. Paul, 1901., pp. 68-69.[

]

- Hind, Henry, Narrative of the Canadian Red River Exploring Expedition of 1857 and of the Assinniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition of 1858. London, 1860. 2 vols. , II, p. 63.[

]

- Ibid., I, p. 163.[

]

- Kane, Paul, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America. London, 1859., pp. 68-71.[

]

- Tanner, John, Narrative of the Captivity of, p. 55.[

]

- Ibid., p. 85.[

]

- Catlin, George, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Conditions of the North American Indians. London, 1844. 2 vols., II, p. 137.[

]

- ibid., p. 138[

]

- McKenney, Thomas L., The Red River. In Masson, p. 269.[

]

- Kane, Paul; Op. Cit., pp. 439-441.[

]