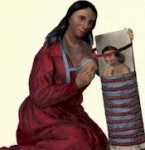

In a preceding volume, we have exhibited a sketch of an Indian mother on a journey, with her child on her back. We present, now, a mother in the act of suckling her infant. The reader will sup pose the cradle before him to have been, only a moment before, leaning against a tree, or a part of the wigwam. The mother, having seated herself on the ground, and disengaged her breast from its covering, has taken the cradle at the top, and is drawing it towards her; while the child, anxious for its nourishment, sends its eyes and lips in the direction of its breast. This is one mode of suckling infants among the Indians. When the child has attained sufficient strength to sit alone, or to walk about, the cradle is dispensed with. Then it is taken by the mother and placed on her lap, she being in a sitting posture; or, if she have occasion to make a journey on foot, a blanket, or part of a blanket, is provided two corners of which she passes round her middle. Holding these with one hand, she takes the child by the arm and shoulder with the other, and slings it upon her back. The child clasps with its arms its mother’s neck, presses its feet and toes inward, against, and, as far as the length of its legs will permit, around her waist. The blanket is then drawn over the child by the remaining two corners, which are now brought over the mother’s shoulder; who, grasping all four of these in her hand, before her, pursues her way. If the child require nourishment, and the mother have time, the blanket is thrown off, and the child is taken by the arm and shoulder, most adroitly replaced upon the ground, received upon the lap of the mother, and nourished. Otherwise, the breast is pressed upward, in the direction of the child’s mouth, till it is able to reach the source of its. nourishment, while the mother pursues her journey. This is the cause of the elongation of the breasts of Indian mothers. They lose almost entirely their natural form.

The cradle, in which the reader will see the little prisoner, is a simple contrivance. A board, shaven thin, is its basis. On this the infant is placed, with its back to the board. At a proper distance, near the lower end, is a projecting piece of wood. This is covered with the softest moss, and, when the cradle is perpendicular, the heels of the infant rest upon it. Before the head of the child there is a hoop, projecting four or five inches from its face. Two holes are bored on either side of the upper end of the board, for the passage of a deer skin, or other cord. This is intended to extend round the forehead of the mother, as is seen in a previous volume, to support the cradle when on her back. Around the board, and the child, bandages are wrapped, beginning at the feet, and winding around till they reach the breast and shoulders, binding the arms and hands to the child’s sides. There is great security in this contrivance. The Indian woman, a slave to the duties of the lodge, with all the fondness of a mother, cannot devote that constant attention to her child which her heart constantly prompts her to bestow. She must often leave it to chop wood, build fires, cook, erect the wigwam, or take it down, make a canoe, or bring home the game which her lord has killed, but which he disdains to shoulder. While thus employed, her infant charge is safe in its rude cradle. If she place it against a tree, or a corner of her lodge, it may be knocked down in her absence. If it fall backwards, then all is safe. If it fall sideways, the arms and hands being confined, no injury is sustained. If on the front, the projecting hoop guards the face and head. The Indian mother would find it difficult to contrive any thing better calculated for her purpose. To this early discipline in the cradle, the Indian owes his erect form; and to the practice, when old enough to be released from the bandages, of bracing himself against his mother’s waist, with his toes inward, may be traced the origin of his straightforward gait, and the position of his foot in walking; which latter is confirmed afterwards by treading in the trails scarcely wider than his foot, cut many inches deep by the travel of centuries.

It is but justice, in this place, to bear our testimony to the maternal affection of the Indian women, in which they fall nothing behind their more civilized and polished sisters. We have often marked the anxiety of an Indian mother, bending over her sick child; her prompt obedience to its calls, her untiring watchfulness, her tender, and, so far as a mother’s love could make it so, refined attentions to its claims upon her tenderness. In times of danger, we have witnessed her anxiety for its security, and her fearless exposure of her own person for its protection. We have looked upon the rough-clad warrior in the solitude of his native forests, attired in the skins of beasts, or wrapped round with his blanket, and realized all our preconceived impressions of his ferocity, and savage-like appearance but, when we have entered the lodge, and beheld, in the untutored mother, and amid the rude circumstances of her condition, the same parental love and tender devotion to her children we had known in other lands, and in earlier years, we have almost forgotten that we stood beside the threshold of the ruthless savage, whose pursuits and feelings we had supposed to have nothing in common with ours, and have felt that, as the children of one Father, we were brothers of the same blood heirs of the same infirmities victims of the same passions; and, though in different degrees, bound down in obedience to the same common feelings of our nature. Persecuted and wronged as he has been, the Indian has experienced the same feelings; and, on more than one occasion, in the rude eloquence of his native tongue, has given them vent, in words not far different from those of Cowper, with which we will conclude this sketch:

“I was born of woman, and drew milk

As sweet as charity from human breasts.

I think, articulate, I laugh, and weep,

And exercise all functions of a man.

______________Pierce my vein;

Take of the crimson stream meand’ring there,

Search it, and prove now if it be not blood,

Congenial with thine own; and, if it be,

What edge of subtlety canst thou suppose

Keen enough, wise and skilful as thou art,

To cut the link of brotherhood by which

One common Maker bound me to the kind?”