In the Southeast, construction stopped at large Swift Creek ceremonial towns such as Leake Mounds in Cartersville, GA and Kolomoki Mounds in extreme southwestern Georgia around 650 AD. Apparently, the populations of these towns dropped substantially. Swift Creek Culture village sites were established in the upper Piedmont and Southern Highlands during this time. The Weeden Island Culture, which replaced Swift Creek in the Gulf Coastal Plain continued. Many of its ceramics had a distinct Caribbean or northern South American “feel” to them.

While the Middle Woodland Cultures in the Southeast seemed to be waning, the population and cultural development in the Lake Okeechobee Region of southern Florida exploded after 600 AD. The people of its many towns did not seem to be economically linked to those living in the interior of the Southeast. (See section on Lake Okeechobee.)

While the Swift Creek Culture was pushed to the margins of lower Southeast, a new Late Woodland manifestation appeared called the Napier Culture. It was concentrated in the southern edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains and Upper Piedmont of Georgia, where precipitation maintained more normal patterns. Napier towns built platform mounds, some of them very large. There was extensive use of the bow & arrow, while corn was cultivated on a larger scale than during Swift Creek period.

Woodstock Culture (c. 800 AD – 1000 AD):

Archaeologist still debate is this was a Late Woodland, Transitional, or Early Mississippian culture. The Woodstock villagers lived in rectangular houses in fortified communities, unlike the round houses in unfortified Swift Creek villages. Their pottery was different than earlier styles. Their village locations were concentrated along the Etowah River, but also found elsewhere in the mountains and Upper Piedmont of Georgia. The Woodstock villagers cultivated large fields of corn, beans and squash, but apparently did not build large mounds. One interpretation of the Woodstock Culture that has NOT been suggested by archaeologists is that they were refugees intruding on a less advanced indigenous population.

Lake Okeechobee Culture (300 AD – 1150 AD)

Lake Okeechobee is a large, shallow lake immediately northwest of the Florida Everglades. As early as 300 AD, the towns and villages of this region seemed to be experiencing accelerating change. The first signs of sophistication and regional government were the construction of dams, canals and raised causeways for roads. Such construction was typical of the Maya Lowlands at that time.

By 700 AD or earlier the densely populated Lake Okeechobee region had developed all the cultural symbols of what is now called the Mississippian Culture. They built ponds and mounds in the shape of “Mississippian” scepters, which are endemic on artistic portrayals of “Mississippian” elite. The “Mississippian” scepters are actually wood and copper replicas of the wood and feather scepters carried by Maya hene ahau or Sun Lords.

Ocmulgee Conurbation (900 AD – 1150 AD)

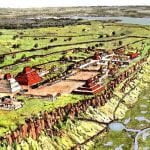

Around 900 AD, newcomers arrived on a natural terrace overlooking the Ocmulgee River in what is now Macon, GA. They established a fortified trading village, which quickly grew into a large acropolis and satellite towns and villages, stretching for at least 12 miles southward in the Ocmulgee Bottoms. The farthest south of the satellite towns in Twiggs County, GA contains 24-28 mounds. Most of the other satellite towns contained one to three mounds. Although many of the satellite towns and villages of Ocmulgee were occupied until the 1500s or later, its acropolis had the exact life span as the Toltec capital of Tula, c. 900 AD – 1150 AD.

All of the cultural and architectural traits of the “Mississippian” Culture appeared at Ocmulgee at least 150 years before they were present at Cahokia. It is now known that the mounds at Cahokia were begun around 1050 AD or later.

The geographical location of Ocmulgee is almost identical to that of the Maya town of Waka in Guatemala. Both sites are located on a terrace, overlooking the fall line of a river. Both sites are 160 miles from the ocean. Both sites were served by an inland port, created from a former horseshoe bend in the river. Both sites were heavily involved with the salt trade. The Maya city of Tikal destroyed much of Waka and killed its elite around 800 AD. Commoners continued to live there until around 880 AD.

The ceramics of Ocmulgee show strong similarity to those produced by the commoners of Waka. The predominant pottery style found at Ocmulgee’s acropolis is virtually identical to Maya Commoner Redware. When Ocmulgee was excavated in the 1930s, archaeologists found hundreds of disk shaped trays that were two to three feet in diameter. They didn’t understand their purpose. Many disappeared from the site. The others were never put on display at the museum. These are Maya-style brine drying trays. They are not found outside of Georgia in North America.

E-tula (Etowah) and Ichese (First phase: 990 AD – 1200 AD)

Around 990 AD newcomers established towns on horseshoe bend at the shoals of the Etowah River in northwest Georgia and two miles downstream from the acropolis on the Ocmulgee River. The settlers produced identical styles of pottery that contrasted with the pottery made elsewhere in the Ocmulgee Conurbation. These settlers built rectangular Totonac style houses, but apparently did not initially build mounds. In the first 200 year occupation of the town sites, they did not build large mounds, the structures were more like clay platforms.

The word, Etula, means “the big town” in Itsate-Maya. The word, Ichese, means “children of corn” in Itsate-Maya and Itsate-Creek. Both towns remained modest in size during their next 200 years of occupation. Around 1200 AD, a catastrophic storm caused both the Ocmulgee and Etowah Rivers to cut across the horseshoe bends where these towns were situated. Both became island towns.

Between 1250 AD and about 1375 AD, E-tula grew explosively to become one of these most powerful towns in the Southeast. The Etowah River’s old channel was drained by a new fortified moat. Its five sided temple mound eventually became one of the largest man-made structures in pre-Columbian North America. Around 1375 AD, the town was sacked. It was later rebuilt as a major vassal of Kusa. The Itsate-Creek word, Etula, became the Muskogee Creek word, etalwa, which now means “large town.”

Ichese grew steadily from around 1200 AD to 1550 AD. Never as large as E-tula, it still became a major regional political center and religious shrine. Around 1400 AD Ichese became one of the most important centers of the Lamar Culture. In fact, the Lamar Culture gets its name from the archaeologists’ name for this archaeological zone, the Lamar Village. By the time, the Hernando de Soto visited the region in the spring of 1540, Ichese was also known by its Muskogee-Creek name of Achese. It means the same as the Itsate-Creek name.

Creek tradition holds that there was a star-gate in the temple on the top of Ichese’s Great Spiral Mound, which enabled extraterrestrials to arrive from another galaxy and some Wind Clan priests to travel to that galaxy. The electromagnetic journey was said to be extremely dangerous. Many priests never returned. Sometimes their dead bodies would suddenly appear in the temple or the priests would be still alive, but terribly deformed.

Some Maya city states also had traditions that certain temples were star gates to another galaxy. To date no scientific proof has been identified that collaborates either the Creek or Maya legends.