The nanisana 1 or Ghost dance is held two or three times during summer or autumn, the first performance in June. 2 Enoch Hoag, the chief, is today in charge. Before his death in 1917 Thomas Wister or Mr. Blue (Gen. I, 10White Moon’s father) who was Enoch Hoag’s younger brother, had been in charge, because, long before the land allotment, 3 it was Mr. Blue who had put into order the dancing grounds (R. Guhayu’ Gudj’axGundj’anao’can: cu, where, hayu’, up, i.e. up creek, where there is a place to dance),–hoeing up the weeds for a dance place and erecting the circular arbor. 4 Because his father owned the dancing ground White Moon says that he and his cousin Clarence Hoag had the right to call a “tribal meeting.”–According to Ingkanish, Mr. Squirrel, who died in 1922, was in charge of the Ghost dance.

Nanisana is danced two nights in succession, with daytime events, such as Turkey dance in the morning, and in the afternoon War dance or handgame. 5

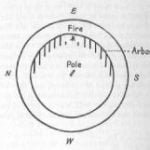

In the nanisana a dance circle is formed around the pole which has been raised in the centre of the dance ground or floor (Fig. 2). The pole is painted dark blue 6) “to represent clouds.” Through the pole from east to west runs an imaginary line, the “road.” The dance and song leader stands on the “road” west of the pole, and facing east. On either side of the leader stand the best singers. There is no drum. The dancers, holding one another by the hand, move singing, in anti-sunwise circuit. At the close of the song the dance and song leader should be standing on the “road.” Between songs people rest and smoke. There is a special closing song, at dawn. After a certain number of circuits are made, the circle pauses with the leader at the south. At the next pause he is at the east, at the next, at the north, at the next, back at the west and with this morning star (naid’achawaniisha) song the dance concludes.

Formerly in the hair of the leader, fastened into the braid at the back and sticking up, was an eagle wing or tail feather, tipped with a downy eagle feather painted red (frontispiece) 7 and from this he was called tsa’nida’a (tsa’, “Mr.,” nida’a, feather erect). On either side stood other tsa’nida’a. To seven men Sitting Bull “gave the feather” and songs. According to White Moon these men were Moon-head (pp. 47 n. 174, 52), White-bread (p. 10), Mr. Blue, Tsa’owisha (John Shemamy) (p. 74), T’amo’, K’aaka’i (Crow) or Billy Wilson, Mr. Squirrel (p. 47). The last four are still living (1921). Crow is very old and feeble. Squirrel as noted on p. 52 is still a Ghost dance leader. He is a brother of the deceased chief at Fort Cobb.

Mr. Blue’s supernatural helper was the fox, and he would hang a fox skin to the top of the pole. 8 At the base of the pole food is set out. After the dance the pole is taken up and placed where it is kept between dances, in the fork of a nearby elm tree.

Mr. Blue determined what was to be danced. On the second night, kak’it’imbin may be danced at the same time nanisana is being danced, or the two may alternate or kak’it’imbin may be danced alone as a preliminary, until the people gather. In this dance there is a drum around which the dancers group, the bunch dancing in sunwise circuit around the dance floor. There is no leader. The songs are contributed by individuals who hear them, they claim, “from the winds or from a bird or something” or dream them. “A fellow will dream of a song or in his dream will hear somebody singing, he wakes up, he remembers the song.” To others the words are unintelligible.

This is a reference to dreaming at any time as well as to the dance trance of which White Moon related nothing further until I asked direct questions. This feature is passing away, 9 he opines; in the summer of 1921 not a single trance occurred. On going into a trance (t’ot’aya, he went off into a trance) a dancer will leave the dance circle, falling down. On coming to, he will sing the song he may have dreamed, standing either near the dance leader or at the pole. There is one man who has the habit of climbing the pole to induce trance. Neither dance leader nor any one else helps nowadays to induce trance. Nor is the red paint, hawanu, any longer used. 10 Nowadays White people take part in Ghost dance celebration.

Ingkanish’s succinct account of the Ghost dance refers to the trance. “Sing favorite song, feel so happy, take them fits, fall down, have a trance, see people, come back and tell what they have seen. Believed world was coming to an end; forgot stock and lost them. Danced in winter, got sick from colds. So Government don’t like Ghost dance and has been stopping it, 11 but it may come back again through Roly (Holy) Rollers, just the same as Ghost dance.”

Citations:

- R. nani’sana’. This word, White Moon thinks, is Arapaho or Cheyenne. It is Arapaho, nänisana, my children (Mooney, 791). A Caddo term proper, according to Mooney, is ă ă kakĭ’mbawi’ut, “the prayer of all to the Father.” According to White Moon, “Father, we pray to” is just a phrase that might be used, for example, were one reproving some one showing improper levity.[

]

- According to Pardon, there has been no performance since before the Great War (1919) when the Government stopped all dances. Pardon refers to the Ghost dance as a negligible matter in quite different terms from those he uses towards the Peyote cult.[

]

- At the great dance under the leadership of Sitting Bull held near the Cheyenne and Arapaho agency in 1890 Caddo were present (Mooney, 898). Dunuhkaido, White Moon thinks Sitting Bull was called, “it sounds familiar,” but of Sitting Bull as the introduces of the cult White Moon knew nothing.[

]

- According to Mooney, of the seven persons selected to be “given the feather” by Sitting Bull of the Arapaho, Nĭshku’ntŭ, Moon-head or John Wilson was chief. Moon-head was half Delaware, one-fourth Caddo, one-fourth French. (He spoke Caddo only.) He was a doctor as well as Ghost dance and Peyote leader. Around his neck he wore the polished tip of a buffalo horn, surrounded by a circlet of downy red feathers, within a circle of badger and owl claws. “The buffalo horn was `god’s heart,’ the red feathers contained his own heart, and the circle of claws represented the world.” In trance he went to the moon. “The moon taught him secrets” (i.e. was his supernatural helper). (“The Ghost Dance Religion,” 903-905).[

]

- Among Pawnee sometime after 1904 hand-game was introduced into the Ghost dance ritual by the dreams of a devotee (Murie, 636).[

]

- Blue was associated with the dead by the Caddo. Fray Francisco Casañas de Jesus Maria wrote that the Indians liked blue “because it was the color of heaven.” Green (identified with blue) pigment has been found in Caddo graves, and grave vessels are smeared with green (Harrington, 288-289[

]

- As a study in acculturation compare with the buckskin-painted picture figured by Mooney, Pl. CIX.[

]

- See p. 59. Choctaw associated the fox with the dead (Swanton 3: 216-217).[

]

- As among Pawnee, Murie, 636.[

]

- See Mooney, 1098.[

]

- Before the world war of 1914 all dancing was stopped and, according to Pardon, since then there has been no Ghost dance performance.[

]