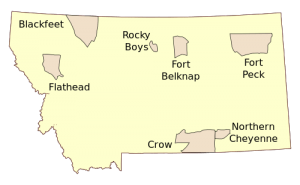

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe occupies a small reservation located in southeastern Montana. The eastern portion of the Reservation lies in Rosebud County, the western portion in Big Horn County. The much larger Crow Reservation abuts Northern Cheyenne lands to the west, while the Tongue River forms the Northern Cheyenne Reservation’s eastern boundary. In all, the Reservation encompasses some 444,775 acres, or 699 square miles. Additionally, the Tribe owns tracts of unpopulated land just south of the Reservation in Montana, and near the sacred Bear Butte in South Dakota. Figure 1-1 shows the Northern Cheyenne Reservation proper and adjacent jurisdictions and features. Figure 1-2 shows the location of the Reservation in relation to existing and proposed energy developments.

Although relatively small as western Indian reservations go, the Northern Cheyenne Reservation is unusual because the Tribe or its individual members own and control almost the entire Reservation land base. Only about 2 percent of the land is fee land (i.e., not held in trust – capable of being bought and sold), and only about 1 percent of the land is owned by non-Indians. None of the Indian-owned land is leased to non-Indians. Tribal and allotted grazing lands are leased to Northern Cheyenne ranchers.

The Cheyennes’ 99 percent ownership and control of the Reservation land base by Northern Cheyenne tribal members is not a historical accident, but the result of determined effort, much sacrifice, and skillful leadership and negotiations by a succession of earlier generations. It is one tangible expression of the value in which the Northern Cheyenne people hold their remaining homeland, which many Tribal members regard as a sacred trust inherited from their forebears.

Northern Cheyenne Culture and Tradition

The Northern Cheyennes’ distinct culture underlies and underlines all of the other, sometimes more measurable, differences that separate the Tribe from neighboring populations. But culture and cultural difference are very difficult for many Euro-Americans to fully appreciate – indeed, almost uniquely difficult. A developed theory of culture and cultural difference is quite recent as such ideas go. It still is often resisted by or only partly assimilated into the legal, policy, and institutional thinking that informs public decision making. Yet it is essential that culture be taken seriously and respectfully as a fundamental reality, in environmental impact statements and land use planning that affects the Northern Cheyenne Reservation. This is necessary if such planning is to benefit the Tribe, and now, if it is to meet minimum legal requirements.

Population of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation

Chapter 3 of this report presents information relating to Northern Cheyenne demographic and economic indicators. According to the 2000 Census, the population of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation is 4,470 persons, of whom 4,029 are Native American. When adjusted for the likely under-count, the actual Reservation population is approximately 5,000.

Many enrolled members of the Tribe also live off the Reservation at any one time. While something over 4,000 Cheyennes live on the Reservation, a recent count of the total enrolled membership of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe tallied about 7,440 persons. Thus, about 3,000 Tribal members live off the Reservation. But the ratio of on-Reservation to off-Reservation populations can shift rapidly. The Reservation and its community remain the homeland and anchor for most tribal members. As a community, and as individuals and families, the Northern Cheyenne generally are less mobile than non-Indians; they less readily pick up their roots and put them down somewhere else. Family members may leave for a while, but they also return. Despite extremely limited housing and other vital public services, changing economic conditions can bring more Tribal members back to the Reservation.

Reservation demographics confirm that the Northern Cheyenne community is a distinct community from other populations and communities in the region. For this reason, it should not be either ignored nor averaged into county-wide or regional analyses for environmental impact statement or land use planning purposes. For instance, the Northern Cheyenne Reservation is much more densely populated than the surrounding highly rural, ranching areas. The age and income profile of the Reservation population is much younger and poorer than non-Indian populations elsewhere in the region.

Many of the ways that the Northern Cheyenne differ from other groups in the area are interrelated, and are the outgrowth of the Tribe’s own unique history and culture. Statistical tables and charts by themselves cannot reveal the history, nor the dynamic social and economic processes, that lie behind the raw numbers. The standard social and economic data presented here needs to be considered in light of the Tribe’s unique history and the particular “niche” it presently occupies in the broader regional social structure and economy.

Northern Cheyenne Economics

It is no secret that Indian reservations are by and large among the poorest regions in the United States. The Northern Cheyenne Reservation is no exception. According to the 1990 census, per capita income on the Reservation was only 48 percent of that enjoyed in off-Reservation areas of Rosebud County, Montana. Median household income was likewise only 45 percent of the comparable figure for neighboring communities in the County. Likewise, the Bureau of Indian Affairs reports that unemployment on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation is a staggering 71 percent, with 1,719 Tribal members unemployed out of a total potential labor force of 2,437.

The intense poverty that afflicts the vast majority of reservations is not inevitable. Reflecting past policies, it is maintained presently by practices, attitudes, and institutions that those past policies entrenched. If opposing institutional arrangements (such as liberalized restrictions on commerce or taxation, for instance) favor Indian tribes who are in a position to take advantage of these arrangements, then tribes can prosper – just as corporations or other entities do who regularly are granted favorable policies. The resulting incomes would not only reduce poverty on the Reservation, but would contribute to the economic vitality of surrounding non-Indian regions. In contrast, however, the vast majority of tribes who are unable to take advantage of such options presently – generally because they are in isolated regions, and remain otherwise subject to entrenched institutions, practices, and attitudes within their regions – remain locked in poverty. In this sense, localized poverty is not so much a condition of a community as it is a relationship between that local community and its region.

The present circumstance, as southeastern Montana faces another energy-boom cycle, may either worsen or alleviate the Northern Cheyenne Tribe’s disadvantaged position within the regional economy. The previous energy development boom in the immediate area, centered on coal mining and power plant construction at Colstrip just north of the Reservation, worsened conditions on the Reservation. These effects have been documented in studies performed in connection with regional coal leasing in the early 1980s, and are now better understood. Chapter 3, Part III of this report provides further explanation of how economic development in the region, if it occurs under conditions that isolate the Cheyenne from its benefits, actually has negative economic impacts on the Reservation.

Ignoring adverse economic impacts in instances like this one has human consequences, as well as economic costs that are not always obvious. In all communities, poverty is linked to increased crime, drug use, and family dysfunction. These negative effects will be amplified in small, close-knit, communities whose members and families have been subjected to physical, sexual, and mental abuse, as the Northern Cheyenne people endured in the early reservation period. The unfortunate effects of such experiences especially impact children and are passed down in families.

These are harsh realities; but as we will see the Tribe and the various social service agencies on the Reservation recognize them, and are dealing with them, and they should not be glossed over in baseline and impacts assessments of the Reservation and its people, either. Thus, in the last part of Chapter 3, we provide stark evidence of the human consequences of the Reservation’s grinding poverty, in the form of increased mortality and morbidity and chemical dependency, among other indicators.

The Cheyenne people widely recognize poverty to be at the root of many of the physical, mental, and social ills that afflict the Cheyenne community. The convergence of poverty, drugs, and the persistent legacies of past practices and policies being noted here brings us to a second major theme of this report: namely, as compared with non-Indian populations in the region, the Northern Cheyenne constitute not just a distinct population, but also one that is uniquely vulnerable. In the context of present proposals for renewed energy development in the immediate vicinity of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation, there is an affirmative responsibility on the part of the federal government to assess, consider, and act to alleviate further preventable adverse impacts to the Reservation and its vulnerable population.

Northern Cheyenne Tribal Government

Chapter 4 presents a description of the Northern Cheyenne Tribal government and the Tribe’s fiscal resources. It should be noted at the outset, however, that prior to extended warfare with Euroamericans in the late nineteenth century, the Cheyenne had already developed an effective, sophisticated political and legal system. The Cheyenne Way, authored jointly by a legal scholar and an anthropologist 1 , revealed the Cheyenne way of jurisprudence through a carefully documented series of case examples based on fieldwork done in the mid-1930s. While different from those of European traditions, Cheyenne ways of governance and dispute resolution nevertheless impressed Llewellyn and Hoebel as complex, subtle, and well-adapted to the Tribe’s nomadic and seasonally dispersed existence. Their work has become a classic of anthropological legal studies. It dispelled the notion, widespread in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, that aboriginal Native American peoples lacked law and government.

Traditional forms of Cheyenne governance, however, could not be maintained through decades of relentless warfare followed by dispersal of the Tribe, and then confinement on the Reservation under Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) rule. In 1936 the Tribe elected to organize itself under the Indian Reorganization Act, adopting a Constitution which provided for an elected Tribal Council, a Tribal President, and a Tribal court. 1996 amendments to the Tribal Constitution provide for a formal separation of powers between the Legislative, Executive and Judicial branches of Tribal government. Tribal government has since grown in size and complexity since 1936 to encompass over 30 executive agencies and departments and many boards and commissions help to oversee these agencies.

Despite these advances in Tribal self-government, the Reservation lacks a vibrant, self-sustaining economic base that would allow the growth of fully autonomous Tribal government institutions. With no tax and minimal enterprise revenues to support the operations of Tribal government, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe and its people remain heavily dependent on a variety of federal programs. Because most of these funds and services are mandated for specific purposes, the Tribe finds itself with almost no discretionary resources. This leaves the Tribe extremely vulnerable to off-Reservation energy development because the Tribe lacks the resources to effectively participate in the complex administrative and legal processes that will ultimately shape that development. In recent years, the Tribe’s discretionary funds have actually been declining as revenues from Tribal grazing and timber lands continue to dwindle.

Northern Cheyenne Reservation Services, Programs and Facilities

Chapter 5 of this report addresses in considerable detail the public services, programs and facilities available to meet the special needs of the Reservation community. The study finds that many public services on the Reservation fall far short of the needs they serve and are inadequate in relation to those enjoyed by more wealthy off-Reservation communities.

The report finds the most severe public service deficits to be in the areas of housing, utilities and fire protection. The Reservation faces a severe housing shortage with more than 800 families needing new housing and fully two-thirds of the existing housing stock in substandard condition. Existing housing programs on the Reservation are barely able to prevent further deterioration in the housing situation let alone address these severe deficiencies.

Several Reservation communities lack access to reliable drinking water supplies, the sewer system in Lame Deer operates in violation of the Clean Water Act, and the Reservation’s solid waste transfer stations have been allowed to become open dumps. The Tribe lacks the resources to fix these problems and must compete for limited sanitation funding with several other Reservations with equally serious deficiencies.

The Reservation’s fire protection system is essentially unfunded. More than half of the fire hydrants in Lame Deer do not properly function and the Tribe lacks a formal spill contingency plan. Due to lack of funding, volunteer fire fighters have only the most basic training and operate with severely outdated equipment.

Law enforcement, transportation and social services are three other areas where public services are deficient. The Reservation is suffering from a crime epidemic with more than 5,000 arrests in the past year alone. The Reservation police force is underfunded and understaffed. There are times in which only one officer is on-duty for the entire Reservation. The Tribal Court lacks adequate facilities and the Tribe’s detention center is chronically overcrowded. Existing law enforcement deficiencies have the potential to be exacerbated by jurisdictional gaps which threaten to make the Reservation a haven for non-Indian lawbreakers.

There is no public transportation on the Reservation. Poverty limits access to reliable private transportation. Although the Reservation’s road network has recently been improved, accident rates on Reservation highways remain much higher than on comparable off-Reservation highway segments. The Reservation lacks basic traffic safety laws or the means to enforce them. Again, the Reservation’s traffic problems are made worse by irresponsible non-Indians who take advantage of the Reservation’s lack of traffic law enforcement.

Social services on the Reservation are deficient in relation to the need engendered by very high rates of poverty. Tribal members are increasingly dropping off the welfare rolls due to onerous eligibility requirements and are being forced to rely on Tribal programs of last resort, such as commodities, emergency food vouchers and low-income energy assistance, to meet their basic physical needs. Child welfare workers operate in a crisis mode almost continuously and are unable to provide the comprehensive services needed to address the root causes of child abuse and neglect. Funding for drug and alcohol treatment is woefully inadequate to serve the needs of a Reservation in which chemical dependency is endemic. Participation in employment and job training programs is high, but waiting lists are long and available jobs scarce even for qualified applicants.

Education and health services are a bright spot in the otherwise gloomy assessment of Reservation services. On-Reservation schools have been upgraded in recent years and Reservation families have a relatively high degree of school choice with the presence of well-funded private and public schools just off the Reservation. The Reservation has its own Tribally controlled community college and a vibrant Head Start program. Nevertheless, student achievement is still low as measured by standardized tests and drop out rates remain unacceptably high.

The Reservation also benefits from a new Health Center which was constructed by the Indian Health Service in 1999. The new Health Center not only brought substantially improved to health care facilities to the Reservation but also resulted in large increases in funding for Tribal health programs. Notwithstanding these improvements, the Reservation still lacks needed inpatient facilities, a dialysis center and various forms of specialty care. The budget for off-Reservation contract care is inadequate to meet current needs.

Natural Resources of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation

The natural resources of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation and adjacent lands and waters are described in Chapter 6. A major focus of the Chapter is on water, a precious resource in an arid region which averages only about 14 inches of rainfall per year. (Water is not only an important economic resource, as Chapter 7 of the report points out, springs and other water bodies are also an important cultural resources for the Tribe.) Chapter 6 discusses the Tribe’s reserved water rights and characterizes the present and potential uses of water that could be affected by CBM and other energy development adjacent to the Reservation. The Chapter also contains data on water quality and information about the Tribe’s water quality standards. In addition to water resources, Chapter 6 also discusses the Reservation’s Class I air-shed, as well as the Reservation’s important forest, range-land, and fish and wildlife resources.

Cultural Resources of the Northern Cheyenne

The final Chapter of the report provides a detailed inventory of Northern Cheyenne cultural resources. Building on the discussion in Chapter 2, this Chapter explains that “cultural resources” are not necessarily limited to specific historical or archeological sites, but also include natural resources that support ceremonial and subsistence uses, and landscapes needed to perform important rituals. These cultural resources can be found both on and off the Reservation and especially in the Tongue River valley, an area that was homesteaded by Tribal members in the 1880s and toward which many Cheyenne still feel an intense bond.

Citations: