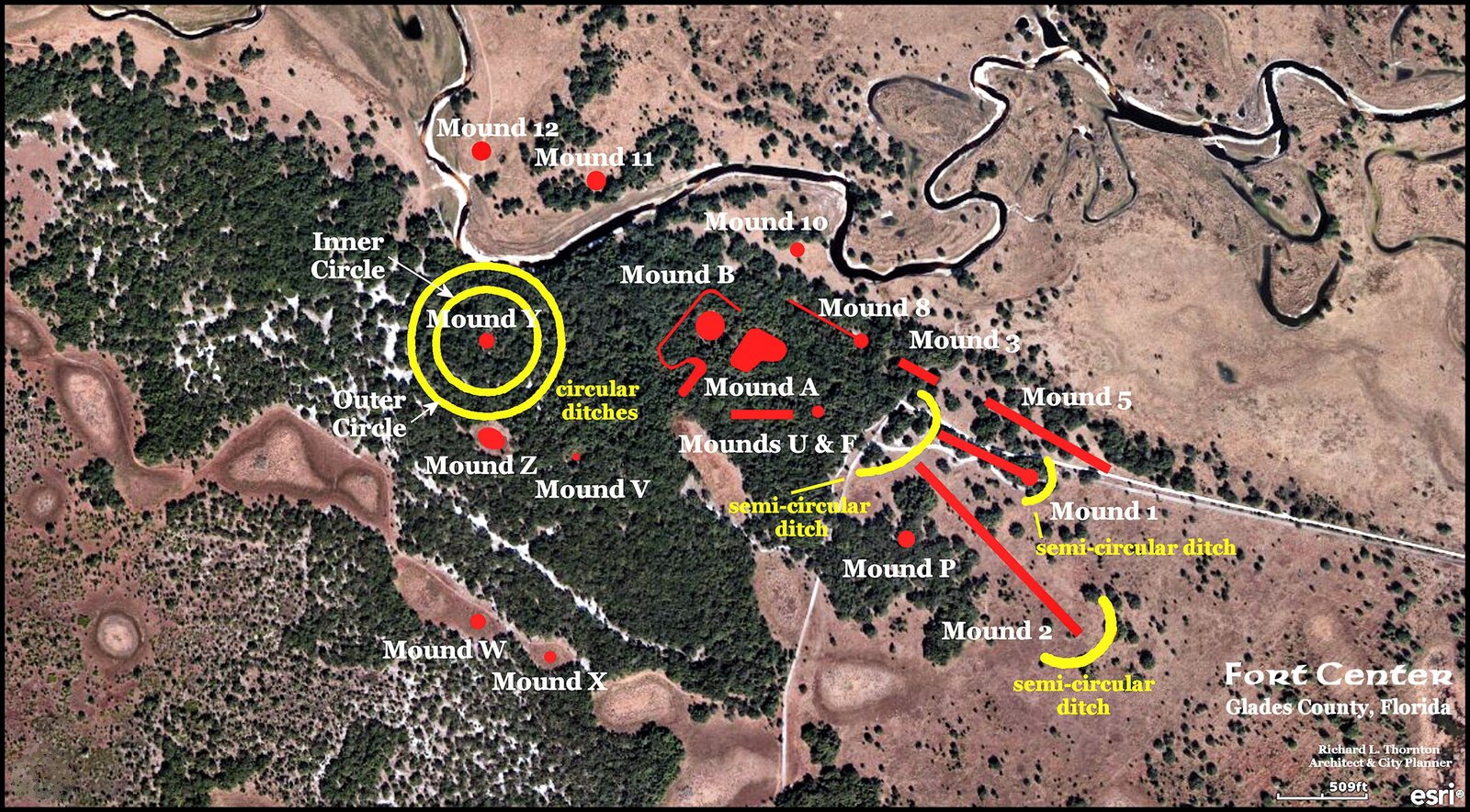

Fort Center was a large ceremonial complex on Fisheating Creek in the northern edge of Glades County, FL that was constructed during the Belle Glade Culture. 1 The visible earthworks occupy an area that is about 1 mile long and ½ mile wide. Fort Center is currently believed to be the oldest center of Belle Glade Culture. 2 However, with so many town and ceremonial sites around Lake Okeechobee being unknown or unstudied, this statement cannot be made with certainty. The site received its name from a small fort erected during the Seminole Wars, which was named after Lt. J. P. Center, who was killed in a battle with the Seminoles. 3 Early settlers thought that the Native American earthworks were the ruins of the fort.

Archaeologist Robert Sears established his professional reputation in the late 1940s with the continuation of excavations at Kolomoki Mounds in deep, southwestern Georgia. 4 The interpretation of the site that gave him national professional credibility turned out to be totally wrong. He placed the construction of Kolomoki in the period after Cahokia Mounds was abandoned (post-1300 AD) which confirmed the belief of Northern archaeologists that Cahokia was the first ceremonial mound center. Later in his life, Sears realized that Kolomoki preceded Cahokia by 800 years. This accurate interpretation of radiocarbon data brought him ostracism from many of the most powerful anthropology professors – living north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Much of the last years of Sears’ exceptional archaeological career were spent at the Fort Center site near Lake Okeechobee, during the late 20th century. 5 His interpretation of the artifacts and architectural evidence discovered were in such stark contrast to the prevailing orthodoxies of his profession, that many of his peers thought him to be a kook. For years, his reports were dismissed as being unreliable. However, in recent decades work by other archeologists have confirmed his interpretation and pushed back the occupation of Fort Center even further. Meanwhile another clique of archaeologists has continued to attack his interpretation of the corn pollen found at several locations within the Fort Center archaeological zone.

During his career, Sears was so ostracized by his professional peers because of Fort Center that he was blocked from publishing his work in mainstream professional journals. 6 In semi-retirement, Sears published articles in the “American Journal of Antiquity and Yachting” that updated his interpretation of Kolomoki Mounds and went into more detail concerning his belief that South Americans immigrated into Southeastern North America.

The pollen of a Mexican Lowland variety of Indian corn was definitely cultivated at Fort Center shrines as early as 850 BC. 7 This tropical corn would not have grown well in more temperate climates. Apparently, the corn was grown in raised beds in which the soil was chemically made less acidic. They were created by digging drainage or irrigation ditches in geometric patterns. Evidence of corn processing includes metates (Mexican style grain grinding stones) plus lime kilns and an abundance of powdered lime. Hydrated lime is used in the processing of corn flour that will be used for tortillas and tamales. It was also used as the principal ingredient of white stucco, which was applied to buildings in the same manner as Maya structures.

The scale of corn cultivation at Fort Center grew far beyond the needs of the local community. It can be assumed that either corn kernels, corn flour, cooked corn products or corn beer was exported to other communities. 8 There is little evidence of corn cultivation in other Lake Okeechobee communities until much later. Indian corn was not grown at a large scale in northern Florida until at least 900 AD.

By 450 BC the scale of the ditches, canals or moats being excavated by the people at Fort Center had become enormous. 9 They averaged six feet in depth and twenty-eight feet wide. One circular ditch constructed during that time period was 1200 feet in diameter and enclosed 23 acres.

Excavations that large probably exceeded the practical needs of agriculture or the assumed needs of ceremonial architecture. They didn’t “go anywhere” so they probably were not used for transportation purposes, but this is still possible. Another explanation is that the large circular ditches were fortifications that served a dual ceremonial purpose.

Mounds of varying shape and size are scattered about the Fort Center site. Some are definitely burial mounds. Others seemed to have been used as bases of buildings – either public or residential. Some mounds are surrounded by ditches or moats. Others are not.

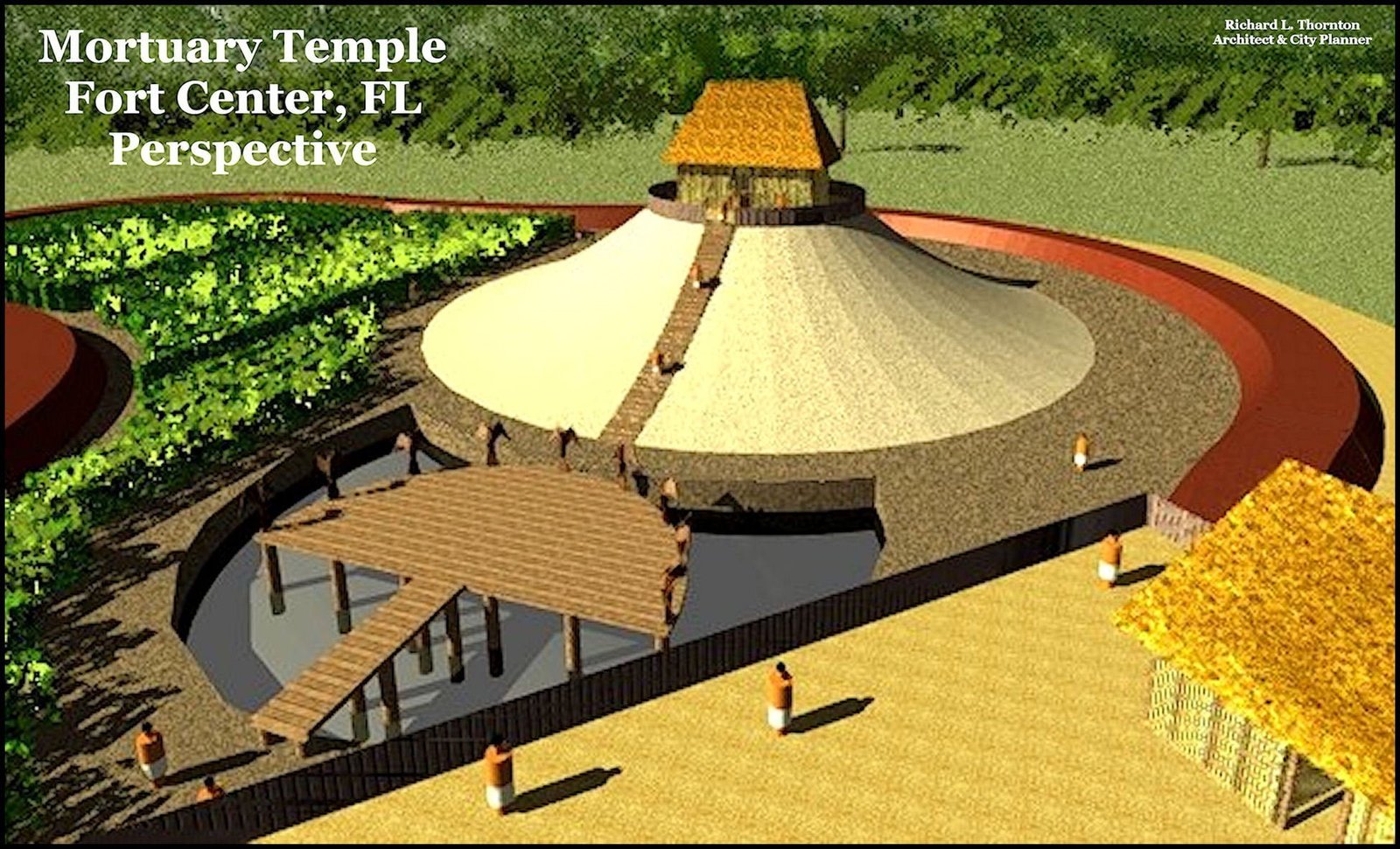

One of the most unusual examples of Native American architecture ever created was a mortuary complex at Fort Center, constructed around 200 AD. The complex included a chevron-shaped earthen berm with rounded ends, a terrace for elite residences, a pond, a “sacred garden” for growing corn, a wooden platform for funerals, a conical mound veneered with shells imported from the coast, and a mortuary temple.

Fort Center seems to have declined in importance throughout the Belle Glade III Period. The massive ceremonial complex at Ortona then became the most important community. Fort Center had only a small population after around 1150 AD. It continued to be a settlement site until around 1700 AD.

Contradicting archaeological reports

Several anthropologists have continued to follow the paths of their professors in attacking Bill Sears’ interpretation of Fort Center. These attacks are focused on the maize pollen. Students are sent to do soil samples of the archaeological site, three decades after its excavation and find no maize pollen. Their reports mirror the attitudes of their professors and deny the existence of the pollen found earlier and neglect to mention the presence of lime powder and metates at several building sites.

Most contradicting reports accurately state that the soil at Fort Center is acidic and contains high levels of aluminum. 10 Therefore, it is not a good location for growing maize. Members of the grass family tend to be stunted or do not grow at all in acidic soil that contains high levels of aluminum. Dairies in such locations are often forced to purchase their hay from other regions where soil calcium levels are higher and aluminum levels are lower.

Another clique of archaeologists admits that Sears found maize pollen, but insist that the source of the pollen was from 20th century farming operations near the archaeological zone. Those same professional papers omit discussion of the fact that the corn was cultivated in man-made soil within raised beds and that alkaline calcium carbonate was found in abundances in and around these beds. Charcoal and ashes were also found in the abundance within the man-made soil of the raised beds. Ashes chemically react with water to create wood ash lye (potassium hydroxide) a highly caustic chemical that quickly neutralizes acidic soils.

These same reports neglect to mention that corn does not grow well in the natural soil of Glades County, Florida. There is virtually no corn grown in the region around Fort Center and the pollen found was linked by Bill Sears to an archaic variety of corn that is not cultivated anywhere in the world today. The Seminole Tribe’s beef operation in Glades County must buy its corn from the northern edge of Florida. 11

The deceptive language used in partisan archaeological reports, along with the omission of factual information to sway opinion, are two of the many obstacles currently affecting the comprehension of the Lake Okeechobee region’s pre-European history. Minimal study has been done on the canals and causeways that linked the towns and villages. None of the satellite villages have been fully studied. This leaves much of the description of the Lake Okeechobee Culture in the realm of speculation.

Citations:

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida.[

]

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida; p. 184.[

]

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida; p. ix, x.[

]

- Memorial to William Hulse Sears (1909-1996) Society for American Archaeology[

]

- Memorial to William Hulse Sears (1909-1996) Society for American Archaeology[

]

- Memorial to William Hulse Sears (1909-1996) Society for American Archaeology[

]

- Kelly, Jennifer A. “Evidence of early corn pollen in peninsular Florida,” Department of Anthropology, University of South Florida.[

]

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1994). Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida; pp. 287-290.[

]

- Morris, Hanna Ruth. “Paleoethnobotanical Investigations at Fort Center (8GL13), Florida” Ohio State University, Department of Anthropology, 2012.[

]

- Morris, Hanna Ruth. “Paleoethnobotanical Investigations at Fort Center (8GL13), Florida” Ohio State University, Department of Anthropology, 2012.[

]

- Bitner, Gary. “Seminole Tribe rolls out new ‘Seminole Pride’ beef brand.” Seminole Tribe of Florida press release. July 24, 2014.[

]