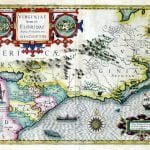

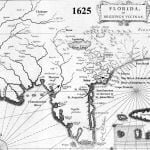

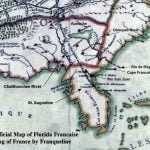

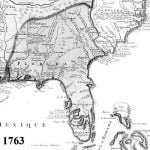

It is a fascinating chapter of American history that until recently was left out of history textbooks. France claimed the region between the Santee River in South Carolina and the St. Marys River in Georgia from 1562 to 1763. The province was called Florida Françoise. Yet France never claimed the St. Johns River Basin where the Fort Caroline National Memorial is now located. How can that be? 1

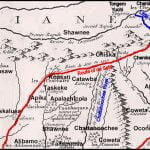

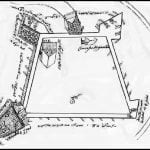

Between 1562 and 1565 French colonists constructed Charlesfort on Parris Island, SC and then, Fort Caroline, somewhere in the region between the Altamaha River, GA and the St. Johns River, FL. Numerous expeditions, lasting as long as several months, were dispatched from Charlesfort by Captain René Goulaine de Laudonniére to explore the interior of the Southeast. Most focused on the mountains and Piedmont of Georgia, where both the French and the Spanish had been told gold was abundant.

Throughout the period in the 16th century, when France was attempting to establish colonies in North America, the leaders of the expeditions were acting under direct orders from King Charles IX. The expedition fleets and the forts on land flew the flag of the King of France. All colonists considered themselves to be loyal subjects of the king, even though the majority were members of one of the Protestant denominations. France was at peace with Spain. At the time, some English privateers were attacking Spanish treasure fleets, but the French did not commit any acts of aggression against Spanish subjects. Spanish military actions against the colonists was ordered by the King of Spain, Phillip II.

The French government sponsored three fleets loaded with supplies, colonists and soldiers over a four year period. They were under the supervision of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, while Jean Ribault was Captain General. Captain René Goulaine de Laudonniére commanded the colonies for most of their duration. All three men were Huguenots. The unstated goal of the colonization efforts was to provide a new home for French Protestants (Huguenots) who currently lived in provinces of France where Roman Catholics were a substantial majority.

In 1560 and 1561, when the colonizing expeditions to North America were planned, France seemed headed toward being a multi-denominational nation with a Protestant majority. Forty years of intermittent persecution of the Protestants had the same effect as Roman persecution of the Christians. There was an accelerating rate conversion to Protestant congregations. The King of France and upper hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church viewed this as a dangerous threat to the powers they had held since the Late Middle Ages.

Historians have interpreted available evidence from that era to mean that over half the French nobility and a much larger percentage of the middle class were Protestants by1560. The Protestants were composed of several denominations that included the Calvinists, Waldensians, Anabaptists and Lutherans. Protestantism was not nearly as popular with the lower class that formed the vast majority of the French population. Some districts were tolerant of multiple denominational preferences. Others were not. Much of Paris was virulently anti-Huguenot.

Roughly 2 million Frenchmen were Calvinists out of a total population of 20 million. There is no accurate estimate for the smaller Protestant denominations. However, this 20% plus minority held disproportionate economic and intellectual influence in France. It was no accident that Huguenots were the leaders in all early colonization efforts. Scholars now believe that Samuel Champlain, the “father of Canada” was a ”low profile” Huguenot, even though by the 1600s Protestants were not (officially) allowed to immigrate to French colonies.

It is an interesting comment on those times that certain segments of the French population suffered disproportionately during the religious wars of the late 1500s. Engravers, printers and book shop owners were almost always sentenced by the French Inquisition to be burned at the stake. Their capital crime was the printing and distribution of bibles! French laws forbade the ownership of bibles by anyone except the clergy and nobility. Bibles were the favorite fuel utilized to burn the victims.

- The First Voyage

On February 15, 1562 the government of France dispatched Captain Jean Ribault with a small fleet to explore the South Atlantic Coast, claim it for the King of France, and identify potential locations for colonies. Unlike colonial expeditions sponsored by Spain and England in that century, the French expedition was extremely well planned, at least on paper. It was financed by the French Crown, whereas Spanish and English colonial attempts were privately capitalized. The members of the expedition included all skills necessary to survive in the New World, including carpenters and ship builders. Admiral de Cologny intended French Florida to become a major center of ship-building, because of the inexhaustible supply of wood on the Southeast. The colony would thrive from the profits of ship-building and not be dependent on support from the French Crown for very long. That was the plan, at least… - The Second Voyage

In early 1562 the government of France dispatched Captain Jean Ribault with a small fleet to explore the South Atlantic Coast; claim it for the King of France; and identify potential locations for colonies. Ribault brought along with him three stone columns displaying the coat of arms of the King of France. He placed one of these columns at the mouth of the River May, which contemporary scholars assume to be the St. Johns River. Ribault’s fleet then sailed northward along the coast, mapping the islands and river outlets, until it reached was is now assumed to be Port Royal Sound. Ribault planted a second column at the mouth of the sound. Most of the expedition’s energies during the short stay of Captains Ribault and René de Laudonniére were focused on constructing a fort and buildings for the 28 men, who were to stay at the new colony while the remainder went to France for more supplies and colonists. The memoirs of the Frenchmen who survived attempts to plant colonies on the South Atlantic Coast describe a very different ethnic pattern than has been assumed by historians and anthropologists during the past 200 years…- Second Voyage Commanded by René Goulaine de Laudonniére

- Where was Fort Caroline?

- Geography Around the Coastal Region of Fort Caroline

- Agriculture of the Coastal Native Americans

- Ethnicity and Political Divisions of Coastal Tribes

- Gold, Silver, Copper and Greenstone

- Early Explorers in the Interior Coastal Region

- The Third Voyage

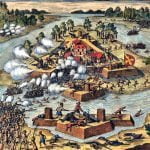

The primary mistake made by Captain de Laudonniére was becoming involved with the inter-provincial wars of his region. He was manipulated several times by the King Satouriona of the Alekmani to send bands of soldiers along with Alikmani war parties in surprise attacks against their enemies. In doing this, the French immediately alienated several provinces that were much more powerful that the Alekmani. In May of 1565 de Laudonniére directed the construction of a new boat for making the crossing to France. However, first he planned to sail around the region to look for food sources… - Aftermath

All images and maps in these articles are from Richard Thornton’s forthcoming book, Earthfast. It is the story of the first European colonies in North America.

Citations:

- Much of the research in this report was drawn from two books by former Congressman Charles Bennett of Florida, which were interpolated with the author’s personal knowledge of Georgia coast – while fishing, canoeing, sailing and camping in the region between Darien, GA and Jacksonville, FL. The author was born in Waycross, GA, is a Creek Indian and is an expert on Muskogean culture. The first book by Bennett, Three Voyages, translated the memoirs of Captain René Goulaine de Laudonniére. The second book by Bennett, De Laudonniére and Fort Caroline, translated the memoirs and letters by other members of the French colonizing expeditions. These books are supplemented by the English translation of Jacques Le Moyne’s illustrated book, Brevis narratio eorum quae in Florida Americai provincia Gallis acciderunt,” Le Moyne was the official artist of the Fort Caroline Colony, and one of the few who survived its massacre by the Spanish. [

]