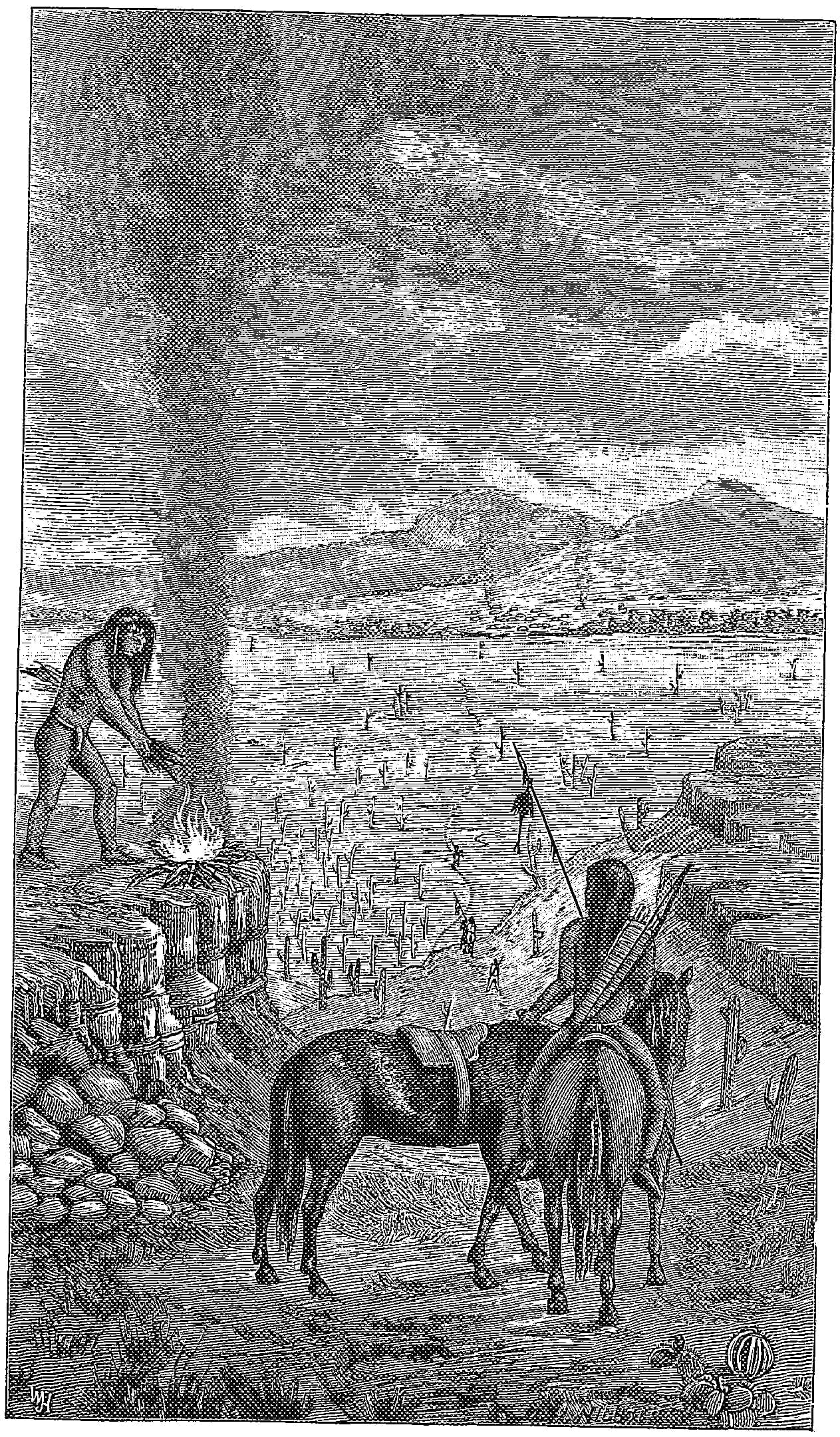

Those noted consist of smoke, fire, or dust signals.

Smoke Signals Generally

They [the Indians] had abandoned the coast, along which bale-fires were left burning and sending up their columns of smoke to advise the distant bands of the arrival of their old enemy. (Schoolcraft’s History, &c., vol. iii, p. 35, giving a condensed account of De Soto’s expedition.)

“Their systems of telegraphs are very peculiar, and though they might seem impracticable at first, yet so thoroughly are they understood by the savages that it is availed of frequently to immense advantage. The most remarkable is by raising smokes, by which many important facts are communicated to a considerable distance and made intelligible by the manner, size, number, or repetition of the smokes, which are commonly raised by firing spots of dry grass.” (Josiah Gregg’s Commerce of the Prairies. New York, 1844, vol. ii, p. 286.)

The highest elevations of land are selected as stations from which signals with smoke are made. These can be seen at a distance of from twenty to fifty miles. By varying the number of columns of smoke different meanings are conveyed. The most simple as well as the most varied mode, and resembling the telegraphic alphabet, is arranged by building a small fire, which is not allowed to blaze; then by placing an armful of partially green grass or weeds over the fire, as if to smother it, a dense white smoke is created, which ordinarily will ascend in a continuous vertical column for hundreds of feet. Having established a current of smoke, the Indian simply takes his blanket and by spreading it over the small pile of weeds or grass from which the smoke takes its source, and properly controlling the edges and corners of the blanket, he confines the smoke, and is in this way able to retain it for several moments. By rapidly displacing the blanket, the operator is enabled to cause a dense volume of smoke to rise, the length or shortness of which, as well as the number and frequency of the columns, he can regulate perfectly, simply by a proper use of the blanket. (Custer’s My life on the Plains, loc. cit., p. 187.)

They gathered an armful of dried grass and weeds, which were placed and carried upon the highest point of the peak, where, everything being in readiness, the match was applied close to the ground; but the blaze was no sooner well lighted and about to envelop the entire amount of grass collected than it was smothered with the unlighted portion. A slender column of gray smoke then began to ascend in a perpendicular column. This was not enough, as it might be taken for the smoke rising from a simple camp-fire. The smoldering grass was then covered with a blanket, the corners of which were held so closely to the ground as to almost completely confine and cut off the column of smoke. Waiting a few moments, until the smoke was beginning to escape from beneath, the blanket was suddenly thrown aside, when a beautiful balloon-shaped column puffed up ward like the white cloud of smoke which attends the discharge of a field-piece. Again casting the blanket on the pile of grass, the column was interrupted as before, and again in due time released, so that a succession of elongated, egg-shaped puffs of smoke kept ascending toward the sky in the most regular manner. This bead-like column of smoke, considering the height from which it began to ascend, was visible from points on the level plain fifty miles distant. (Ib., p. 217.)

The following extracts are made from Fremont’s First and Second Expeditions, 1842-3-4, Ex. Doc., 28th Cong. 2d Session, Senate, Washington, 1845:

“Columns of smoke rose over the country at scattered intervalssignals by which the Indians here, as elsewhere, communicate to each other that enemies are in the country,” p. 220. This was January 18, 1844, in the vicinity of Pyramid Lake, and perhaps the signalists were Pai-Utes.

“While we were speaking, a smoke rose suddenly from the cottonwood grove below, which plainly told us what had befallen him [Tabeau]; it was raised to inform the surrounding Indians that a blow had been struck, and to tell them to be on their guard,” p. 268, 269. This was on May 5, 1844, near the Rio Virgen, Utah, and was narrated of “Diggers,” probably Chemehuevas.

Arrival of a Party at an Appointed Place, When All is Safe

This is made by sending upward one column of smoke from, a fire partially smothered by green grass. This is only used by previous agreement, and if seen by friends of the party, the signal is answered in the same manner. But should either party discover the presence of enemies, no signal would be made, but the fact would be communicated by a runner. (Dakota I.)

Success of a War Party

Whenever a war party, consisting of either Pima, Papago, or Maricopa Indians, returned from an expedition into the Apache country, their success was announced from the first and most distant elevation visible from their settlements. The number of scalps secured was shown by a corresponding number of columns of smoke, arranged in a horizontal line, side by side, so as to be distinguishable by the observers. When the returning party was unsuccessful, no such signals were made. (Pima and Papago I.) Fig. 339. A similar custom appears to have existed among the Ponkas, although the custom has apparently been discontinued by them, as shown in the following proper name: Cú-de gá-xe, Smoke maker: He who made a smoke by burning grass returning from war.