There is no art of higher pretensions to supernatural or divine power, among the professors of the Native American mysteries, than those which are made in the exhibitions of the sacred Jeesukawin. It is the ancient art of the seer or prophet, which has been noticed as existing among all these tribes, from the earliest period of their discovery. To jeesuká, in the language of the Ojibwas is to mutter or peep. The word is taken from the utterance of sounds of the human voice, low on the ground. This is the position in which the response is made by the seer or prophet, who is called jossakeed. Powwow was a term of precisely the same import, used in the respective eras of the settlement of Virginia and of New England. Every tribe has a word to denote the same act, or art, and this term is inflected or varied according to the principles of the different languages, to distinguish the actor from the act, and from the place of the act, or lodge. Thus, jeesuká, (to prophesy,) in the language above denoted, is rendered a noun by the inflection win, making jeesukáwin (prophecy) . To denote the actor, the sound of the letter d is added to the first person singular of the infinitive, and, by a rule of the permutation of the vowels, in making nouns personal from nouns impersonal, the long sounds of e and a are changed to o and e, making jossakeed, a prophet or seer. To describe the lodge, the first person of the infinitive singular is inflected by un, at the same time the sound of a is changed to au, rendering the word jeesukaun (a prophet’s lodge).

To prepare the operator in these mysteries, for answering questions, a lodge is erected by driving stout poles, or saplings, in a circle, and swathing them round tightly from the ground to the top with skins, drawing the poles closer at each turn or wind, so that the structure represents a rather acute pyramid. The number of poles is prescribed by the jossakeed, and the kind of wood. There are, some times, perhaps generally, ten poles, each of a different kind of wood. When this structure has been finished, the operator crawls in, by forcing his way under the skin at the ground, taking with him his drum, and scarcely anything beside. He begins his supplications by kneeling and bending his body very low, so as almost to touch the ground. When his incantations and songs have been continued the requisite time, and he professes to have called around him the spirits, or gods, upon whom he relies, he announces his readiness to the assembled multitude without, to give responses. And no ancient oracle of heathen mysticism not even “Diana of the Ephesians,” ever more completely riveted the popular belief, than do these modern oracles among the North American tribes.

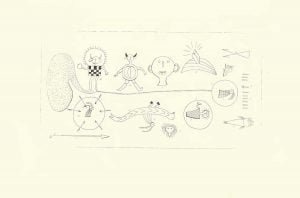

The following pictographic signs, used in this art, represented in Plate 49, B, comprise the spirits, or gods, relied upon by a noted prophet of the Ottawas, called Chusco. 1 They were drawn on paper from his description, at a period when he had, in his own words, “thrown these symbolic devices away,” and united himself to a Christian mission church. They do not, therefore, fully show, but rather imitate the Indian method of drawing, are not intended to copy it, and are only given as exhibiting the mode of denoting power or divinity. He was, at this time, nearly 70; he did not hesitate to declare that he supplicated the great impersonation of the power of Evil, in these mysteries; he was not pressed for the actual words of his songs, and he did not, voluntarily, repeat them.

Number 1 represents the turtle, an object held in great respect, in all Indian reminiscence. It is believed to be, in all cases, a symbol of the earth, and is addressed as a mother. Number 2 is the swan, a bird whose noble shape and motions, commend it, as the impersonation of a spiritual power. The woodpecker (number 3,) the crow (number 4,) and the crane (number 5,) were each addressed as objects of a peculiar and benign influence, and, with the two preceding, were the objects of his incantations and supplications. The figure of the hand (number 6,) is emblematic of the prophetic art. Half-Circles denote the universality of the power of the bird or animal figured. The Indians are not acquainted with the true figure of the globe, but depict the sky as a half-circle.

Chusco practised the prophet’s art, for a great number of years, at his native village of L’Arbre Croche, on Lake Michigan, and also at Michillimackinac, where he died, at an advanced age, in 1838. There also came to reside in the vicinity of the latter place, a prophetess, from Chegoimegon, on the shores of Lake Superior. She was a descendant, in a direct line, from one of the principal Chippewa families, the noted Wabojeeg, who was the ruling chief in that quarter. Pictorial devices, which refer to the Jeesukawin, have been less easily accessible than any other branch. There is a feeling of sacredness and secrecy connected with them, which prevents their being revealed, even to the uninitiated Indians. It is the only branch of their art of picture writing, which is withheld from common use. Signs of the medáwin, and the wábeno; of hunting, sepulture, war, and other objects, are more or less known to all, and are accessible to all, who are admitted to the secret societies. But the prophetic art exists by itself. It is exclusive, peculiar, personally experimental. It was owing to the same fact, which had brought Chusco within the pale of inquiry, that also revealed the gods of OGEE-WY-AHN-OQUT-O-KWA, or the prophetess of Chegoimegon. She had felt and acknowledged the truth of the exhortations of one of the native preachers from the shores of Lake Ontario, in Canada, the noted John Sunday, and had united herself to a missionary church. At this period, she was baptized, and subsequently married an Indian convert, called Wabdse, or the Hare, on which occasion she relinquished her former name of Ogeewyahnoquot Okwa, and assumed that of Wabose.

Plate 55 exhibits the gods of Catherine Wabose, as drawn by herself, and carefully transcribed from a larger sheet. This curious pictograph depicts the objects of a sacred vision, to which she looks back as the date of her revelations, and it reveals, at once, a singular chapter in the art of symbolic writing, and of Indian superstitions. The figures, which will be more fully explained by the narrative which she gave of her early devotion to this art. are as follows: Number 2. Ogeewyahnoquot Okwa, the Prophetess. The marks at Number 3 denote the number of days of her initiatory fast, the day of her vision being marked with a cross. Number 4 represents the path of her aerial visit. Number 6, the moon, with a lambent flame. Number 9, the everlasting standing woman. Number 10, the Little Man-spirit. Number 11, Osha-wanegeezhig, or the bright blue sky. Number 12, the upper heavens. Number 15, the trial of prickles. Number 13, a kind of fabulous fish. Number 8, the sun. Number 18, an orbicular spirit resembling a flying woodpecker. Number 19 is the symbol of her present name. Number 20, a kind of fish. Number 16, a symbol of harm.

Catherine Wabose, the name prefigured by Number 19, was still living at the last accounts. She is a female of a good natural intellect, great shrewdness of observation, and some powers of induction and forecast, living amid mixed clans who are not characterized by either. She was far superior, in these respects, to the aged Ottawa prophet, Chusco, whose secret devices are given above. In order to understand the force and character of her delineations, it was deemed important to obtain the history of the operations of her mind under the influence of her primary periodical fast. This she related in the Indian tongue to Mrs. Schoolcraft, who took it down from her lips in the following words. The name of Catherine, it may be premised, was given to her on her being baptized as a member of the Methodist church. It is owing to this act, indeed, and her being convinced of the error of the Jeesukawin in all its forms, that we are indebted for the revelation of her prophetical experience.

“When I was a girl,” she said, “of about twelve or thirteen years of age, my mother told me to look out for something that would happen to me. Accordingly, one morning early, in the middle of winter, I found an unusual sign, and ran off as far from the lodge as I could, and remained there until my mother came and found me out. She knew what was the matter, and brought me nearer to the family lodge, and bade me help her in making a small lodge of branches of the spruce tree. She told me to remain there, and keep away from every one, and, as a diversion, to keep myself employed in chopping wood, and that she would bring me plenty of prepared bass-wood bark to twist into twine. She told me she would come to see me in two days, and that, in the mean time, I must not even taste snow.

“I did as directed. At the end of two days she came to see me. I thought she would surely bring me something to eat, but, to my disappointment, she brought nothing. I suffered more from thirst than hunger, though I felt my stomach gnawing. My mother sat quietly down and said, (after ascertaining that I had not tasted any thing, as she directed,) My child, you are the youngest of your sisters, and none are now left me of all my sons and children, but you four, alluding to her two elder sisters, herself, and a little son, still a mere lad. Who, she continued, will take care of us poor women? Now, my daughter, listen to me, and try to obey. Blacken your face and fast really, that the Master of Life may have pity on you and me, and on us all. Do not in the least deviate from my counsels, and in two days more I will come to you. He will help you, if you are determined to do what is right, and tell me whether you are favored or not, by the true Great Spirit; and if your visions are not good, reject them. So saying, she departed.

“I took my little hatchet and cut plenty of wood, and twisted the cord that was to be used in sewing ap-puh-way-oon-un, or mats, for the use of the family. Gradually I began to feel less appetite, but my thirst continued; still I was fearful of touching the snow to allay it, by sucking it, as my mother had told me that if I did so, though secretly, the Great Spirit would see me, and the lesser spirits also, and that my fasting would be of no use. So I continued to fast till the fourth day, when my mother came with a little tin dish, and filling it with snow, she came to my lodge, and was well pleased to find that I had followed her injunctions. She melted the snow, and told me to drink it. I did so, and felt refreshed, but had a desire for more, which she told me would not do, and I contented myself with what she had given me. She again told me to get and follow a good vision; a vision that might not only do us good, but also benefit mankind, if I could. She then left me, and for two days she did not come near me, nor any human being, and I was left to my own reflections. The night of the sixth day I fancied a voice called to me, and said, Poor child! I pity your condition; come, you are invited this way; and I thought the voice proceeded from a certain distance from my lodge. I obeyed the summons, and, going to the spot from which the voice came, found a thin shining path, like a silver cord, which I followed. It led straight forward, and, it seemed, upward (No. 5). After going a short distance, I stood still, and saw on my right hand the new moon, with a flame rising from the top like a candle, which threw around a broad light (No. 6). On the left appeared the sun, near the point of its setting (No. 8). I went on, and I beheld on my right the face of Kau-ge-gay-be-qua, or the everlasting standing woman, (No. 5,) who told me her name, and said to me, I give you my name, and you may give it to another. I also give you that which I have, life everlasting. I give you long life on the earth, and skill in saving life in others. Go, you are called on high.

“I went on, and saw a man standing, with a large circular body, and rays from his head, like horns. (No. 6.) He said, Fear not; my name is Monido-Wininees, or the Little Man-spirit. I give this name to your first son. It is my life. Go to the place you are called to visit. I followed the path till I could see that it led up to an opening in the sky, when I heard a voice, and standing still, saw the figure of a man standing near the path, whose head was surrounded with a brilliant halo, and his breast was covered with squares. (No. 11.) He said to me, Look at me; my name is O-Shau-wau-e-geeghick, or the Bright Blue Sky. I am the veil that covers the opening into the sky. Stand and listen to me. Do not be afraid. I am going to endow you with gifts of life, and put you in array that you may withstand and endure. Immediately I saw myself encircled with bright points, which rested against me like needles, but gave me no pain, and they fell at my feet. (No. 9.) This was repeated several times, and at each time they fell to the ground. He said, Wait, and do not fear, till I have said and done all I am about to do. I then felt different instruments, first like awls, and then like nails, stuck into my flesh, but neither did they give me pain, but, like the needles, fell at my feet as often as they appeared. He then said, That is good, meaning my trial by these points; you will see length of days. Advance a little farther, said he. I did so, and stood at the commencement of the opening. You have arrived, said he, at the limit you cannot pass. I give you my name; you can give it to another. Now, return! Look around you. There is a conveyance for you. (No. 13.) Do not be afraid to get on its back, and when you get to your lodge, you must take that which sustains the human body. I turned, and saw a kind of fish swimming in the air, and getting upon it as directed, was carried back with celerity, my hair floating behind me in the air. And as soon as I got back, my vision ceased.

“In the morning, being the sixth day of my fast, my mother came with a little bit of dried trout. But such was my sensitiveness to all sounds, and my increased power of scent, produced by fasting, that before she came in sight I heard her while a great way off; and when she came in I could not bear the smell of the fish, or herself either. She said, I have brought something for you to eat, only a mouthful, to prevent your dying. She prepared to cook it, but I said, Mother, forbear, I do not wish to eat it the smell is offensive to me. She accordingly left off preparing to cook the fish, and again encouraged me to persevere, and try to become a comfort to her in her old age and bereaved state, and left me.

“I attempted to cut wood as usual, but in the effort I fell back on the snow from exhaustion, and lay some time; at last I made an effort and rose, and went to my lodge and lay down. I again saw the vision, and each person who had before spoken to me, and heard the promises of different kinds made to me, and the songs. I went the same path which I had pursued before, and met with the same reception. I also had another vision, or celestial visit, which I shall presently relate. My mother came again on the seventh day, and brought me some pounded corn boiled in snow water, for, she said, I must not drink water from lake or river. After taking it I related my vision to her. She said it was good, and spoke to me to continue my fast three days longer. I did so: at the end of which she took me home, and made a feast in honor of my success, and invited a great many guests. I was told to eat sparingly, and to take nothing too hearty or substantial; but this was unnecessary, for my abstinence had made my senses so acute, that all animal food had a gross and disagreeable odor.

“After the seventh day of my fast, (she continued,) while I was lying in my lodge, I saw a dark round object descending from the sky, like a round stone, and enter my lodge. As it came near I saw that it had small feet and hands like a human body.

“It spoke to me, and said, I give you the gift of seeing into futurity, that you may use it for the benefit of yourself and the Indians your relations and tribes-people. It then departed, but as it went away it assumed wings, and looked to me like the redheaded woodpecker in flight.

“In consequence of being thus favored, I assumed the arts of the Jeesukawin, and a prophetess, but never those of a Wabeno. The first time I exercised the prophetical art was at the strong and repeated solicitations of my friends. It was in the winter season, and they were then encamped west of the Wisacoda, or Brule river of Lake Superior, and between it and the plains west. There were, besides my mother s family and relatives, a considerable number of families. They had been some time at the place, and were near starving, as they could find no game. One evening the chief of the party came into my mother s lodge. I had lain down, and was supposed to be asleep, and he requested of my mother that she would allow me to try my skill to relieve them. My mother spoke to me, and after some conversation, she gave her consent. I told them to build the Jee-suk-aun, or prophet s lodge, strong, and gave particular directions for it. I directed that it should consist of ten posts or saplings, each of a different kind of wood, which I named. When it was finished, and tightly wound with skins, the entire population of the encampment assembled around it, and I went in, taking only a small drum. I immediately knelt down, and holding my head near the ground in a position, as near as may be, prostrate, began beating my drum, and reciting my songs or incantations. The lodge commenced shaking violently, by supernatural means. I knew this by the compressed current of air above, and the noise of motion. This being regarded by me and by all without as a proof of the presence of the spirits I consulted, I ceased beating and singing, and lay still, waiting for questions, in the position I had at first assumed.

“The first question put to me was in relation to the game, and where it was to be found. The response was given by the orbicular spirit, who had appeared to me. He said, How shortsighted you are! If you will go in a west direction you will find game in abundance. Next day the camp was broken up, and they all moved westward, the hunters, as usual, going far ahead. They had not proceeded far beyond the bounds of their former hunting circle when they came upon tracks of moose, and that day they killed a female, and two young moose nearly full-grown. They pitched their encampment anew, and had abundance of animal food in this new position.

“My reputation was established by this success, and I was afterwards noted in the tribe in the art of a Meda-woman, and sung the songs which I have given to you. About four years after, I was married to Mush Kow Egeezhick, or the Strong Sky, who was a very active and successful hunter, and kept his lodge well supplied with food; and we lived happy. After I had had two children, a girl and a boy, we went out, as is the custom of the Indians in the spring, to visit the white settlements. One night, while we were encamped at the head of the portage at Pauwating, (the Falls of St. Mary’s,) angry words passed between my husband and a half-Frenchman named Gaultier, who, with his two cousins, in the course of the dispute, drew their knives and a tomahawk, and stabbed and cut him in four or five places, in his body, head, and thighs. This happened the first year that the Americans came to that place, (1822.) He had gone out, at a late hour in the evening, to visit the tent of Gaultier. Having been urged by one of the trader s men to take liquor that evening, and it being already late, I desired him not to go, but to defer his visit till next day; and, after he had left the lodge, I felt a sudden presentiment of evil, and I went after him, and renewed my efforts in vain. He told me to return, and as I had two children in the lodge, the youngest of whom, a boy, was still in his cradle, and then ill, I sat up with him late, and waited and waited, till a late hour, and then fell asleep from exhaustion. I slept very sound. The first I knew was a violent shaking from a girl, a niece of Gaultier s, who told me my husband and Gaultier were all the time quarreling. I arose, and went up the stream to Gaultier s campfire; it was nearly out, and I tried to make it blaze. I looked into his tent, but all was dark, and not a soul there. They had suddenly fled, although I did not, at the moment, know the cause. I tried to make a light to find my husband, but could find nothing dry, for it had rained very hard the day before. After being out a while my vision became clearer, and, turning toward the riverside, I saw a dark object lying near the shore, on a grassy opening. I was attracted by something glistening, which turned out to be his earrings. I thought he was asleep, and in stooping to awake him I slipped, and fell on my knees. I had slipped in his blood on the grass, and, putting my hand on his face, found him dead. In the morning the Indian agent came with soldiers from the fort to see what had happened, but the murderer and all his bloody gang of relatives had fled. The agent gave orders to have the body buried in the old Indian burial-ground below the Falls.

“My aged mother was encamped about a mile off at this time. I took my two children in the morning, and fled to her lodge. She had just heard of the murder, and was crying as I entered. I reminded her that it was an act of Providence, to which we must submit. She said it was for me and my poor helpless children that she was crying that I was left, as she had been years before, with nobody to provide for us. With her I returned to my native country at Chegoimegan on Lake Superior.”

The preceding narrative is taken from the verbal relation of Catherine Wabose, or Ogeewyahnackwut Oquay, who is now in about the forty-first year of her age. A few facts may be added to indicate the steps by which she finally renounced a reliance on these mystical ceremonies, and was led to communicate the information, together with the kekenowin of her visions, and songs subjoined. In the third year after the assassination of her first husband, she married Minanockwut, or the Fair Cloud, his half-brother, by whom she had two children, both daughters. He was in a few years attacked with a complaint of the head, which affected his reason, and of which he died. It was in the winter season that this happened, and as they were inland at their sugar camp, she, with the aid of her children, placed the corpse on a hand-sled, and drew it many miles through the woods to the river’s banks, that he might be buried with his tribe.

She was still called to bear other trials in the course of a few years, which would have broken down a mind of less native strength than hers. Her son, by Strong Sky, sickened at an age when he began to be useful, and after lingering for a time, died. A day or two before his departure, he related to her such a dream of the Great Spirit, as He is known and worshiped by the whites, and of his being clothed by him with a white garment, that her mind was much affected by it, and led to question in some measure, the soundness of her religious views. Not long afterwards one of her little daughters was also removed by death, and according to her own apt interpretation of a “part of her virginal vision, she seemed, indeed, to be pricked with metallic points. While these dispensations rested deeply on her mind, and she felt herself to be the subject of afflictions which appeared to have an ulterior object, the Ojibwa evangelist, John Sunday, visited that part of the country, and explained to her the doctrine of a better revelation which came, indeed, ” from above,” and under his teaching, she renounced the calling of a prophetess, which she had so long practiced, and became a member of the Methodist Episcopal church, and was baptized by the name of Catherine. She says, that the wine she partook of at the communion-table at that time, and at subsequent times, is the only form of spirits she has ever tasted. Her trials were not, however, at an end, though they were mitigated by reflections of a consolatory character. The spring of 1836 developed, in the constitution of her eldest daughter and child, Charlotte Jane, a rapid consumption, which brought her in the month of April to her grave, in her seventeenth year. This young girl exhibited very amiable traits of character, united with an agreeable person. She was taken into my family, after the assassination of her father, in 1822, and educated and instructed under the personal care of Mrs. Schoolcraft, who cherished her as a tender plant from the wilderness. When she had mastered her letters, her catechism, and the commandments, at an early age, she was led on by degrees, from one attainment to another in moral knowledge, till she had acquired the intelligence and deportment, which fitted her to take her place in civilized life. She united with the Presbyterian Church at Michillimackinac, and is buried in its precincts, having exhibited to the end of her life very pleasing and increasing proofs of her reliance upon, and acceptance by a crucified Redeemer.

Prior to the death of her daughter, Catherine had married her third husband, in Nau-We-Kwaish-kum, alias James Wabose, an Ojibwa who was also, and continues to be a member of the Methodist society. By this marriage she had two children, both males, the loss of one of whom has been added to the number of her trials. But the only effect of this bereavement was to strengthen her faith, and by daily renewals of her confidence in the Savior to establish herself in piety.

These particulars, it is conceived, will afford a clear and satisfactory chain of evidence of the truth of her narrative, and the reasons why she has been willing to impart secrets of her past life which have heretofore been studiously concealed, as she remarks, even from her nearest friends.

The following comprises an explanation of her Kekenowin (Plate 55), which have been mentioned in the account of her vision:

Figure 1. A lodge of separation and fasting.

Figure 2. Ogeewyahn akwut oquay.

Figure 3. Denotes the number of days she fasted.

Figure 4. The day on which the vision appeared.

Figure 5. The point from which the first voice proceeded, and the commencement of the path she pursued.

Figure 6. The new moon, with a lambent flame.

Figure 7. The sun, near its approach to the horizon.

Figure 8. The figure of a man in the sun, holding some object which she did not recognize, but supposes to have been a book.

Figure 9. The head of a female spirit called Kaugegaybekwa, or the Everlasting Woman.

Figure 10. A male spirit, called Monedowininees, or the Little Spirit Man.

Figure 11. The principal spirit revealed to her, called Ozhawwunuhkogeezhig, or the Blue Sky.

Figure 12. An orifice in the heavens, called Pug-un-ai-au-geezhig.

Figure 13. A nondescript fish prepared to carry her back.

Figure 14. Ogeewyahn ackwut oquay, sitting on the fish.

Figure 15. The ultimate point attained by her in her bright path leading to the sky, where she underwent the trial of symbolical prickles.

Figure 16. A magic arrow.

Figure 17. Symbol of a woodpecker.

Figure 18. Symbol of her husband s name.

Figure 19. Symbol of the catfish.

The subjoined specimens of her hieratic songs and hymns are taken down verbatim. It is a peculiarity observed in this and other instances of the kind, that the words of these chants are never repeated by the natives without the tune or air, which was full of intonation, and uttered in so hollow and suspended, or inhaled a voice, that it would require a practiced composer to note it down. The chorus is not less peculiarly fixed, and some of its guttural tones are startling. These hymns are to be read from top to bottom.

Prophetic Powers.

1.

| Wi Ta Kwa Yaug Gee Zhik Au |

Wa Win Dah Go Je Naun In A |

Wi Ya Kwa Yaug Gee Zhik Au |

Wa Win Dah Go Je Naun In A (Repeat.) |

| At the place of light At the end of the sky I (the Great Spirit) Come and hang Bright sign. |

|||

| (Chorus of strongly accented and deeply uttered syllables.) | |||

| 2 | |||

| Yau Ne Mud Wa Aus Se Doan Ain Yaun |

Yau Ne Mud Wa Aus Se Doan Ain Yaun (Repeat.) |

||

| Lo! with the sound of my voice, (The prophet s voice) I make my sacred lodge to shake (By unseen hands my lodge to shake,) My sacred lodge. |

|||

| Chorus, &c. 3. |

|||

| Haih! | Wau | Zhik | |

| Wau | Nah | A. | |

| Bish | Kwud | ||

| Kau | Oong | ||

| Gau | Haih | ||

| Gee | Gee (Repeat.) | ||

| Haih! the white bird of omen, He flies around the clouds and skies (He sees, unuttered sight!) Around the clouds and skies By his bright eyes I see I see I know. Chorus, &c. |

|||

The following chants embody the responses of the Deity invoked. They sufficiently denote a fact, which has indeed obtruded itself in other instances, that the sun is not only often employed as a symbol of the Great Spirit, but is worshiped, also, as the Great Spirit himself.

1. Chants to the Deity.

1.

Och auw naun na wau do

Och auw naun na wau do

Och auw naun na wau do

Och auw naun na wau do.

Heh! heh! heh ! heh !

I am the living body of the Great Spirit above,

(The Great Spirit, the Ever-living Spirit above,)

The living body of the Great Spirit,

(Whom all must heed.)

(Sharp and peculiar chorus, untranslatable.)

2.

Mish e mon dau kwuh

Mish e mon dau kwuh

Ne maun was sa hah kee

Ne maun was sa hah kee.

Way, ho! ho! ho! ho!

I am the Great Spirit of the sky,

The overshadowing power,

I illumine earth, I illumine heaven.

(Slow, hollow, peculiar chorus.)

3.

Ah wauh wa naun e dowh

Ah wauh wa naun e dowh

Ah wauh wa naun e dowh

Ah wauh wa naun e dowh.

Way, ho! ho! ho! ho!

Ah say! what Spirit, or Body, is this Body?

(That fills the world around, Speak, man!) ah say!

What Spirit, or Body, is this Body?

(Chorus as in the preceding, with voice and drum.)

2. Hymns to the Sun.

4.

Kee zhig maid wa woash kum aun

Kee zhig maid wa woash kum aun. (Repeat four times.)

A! a! a! ha! aha!

The sky or day I tread upon, that makes a noise.

(I Ge Zis Maker of light.)

5.

Wain je gwo dow aid, gee zhick o ka

Ap pe wain ah ge me e go yaun.

A! a! a! ha! aha!

The place where it sinks down the maker of day.

When I was first ordained to be. (I Ge Zis.)

3. In the Medáwin.

6.

Nim ba na see wa yaun e

Nim ba na see wa yaun e. (Repeat four times.)

A! a! a! ha! aha!

My bird’s skin my bird s skin, &c.

7.

Ning ga kake o wy aun a

Ning ga kake o wy aun a (Repeat” four times.)

Ap pee i aun je ug wa.

A! a! a! ha! aha!

My hawk’s skin my hawk’s skin,

The time I transformed it, &c.

4. To the Great Spirit.

8.

In ah wau how mon e do

In ah wau how mon e do

I au au jim ind

Gee zhik oong a bid. (Repeat four times.)

A! a! a! ha! aha!

Look thou at the Spirit. It is he that is spoken of who stays our lives who abides in the sky.

Such is the Indian system of the higher Jeesukáwin. To speak, as it were, from the secrecy of the Indian mind, the symbols illustrative of its superstitions, requires perseverance of investigation, under the most favorable circumstances. Questions which are resisted in one form, or in a particular frame of mind, on the part of the respondent, may be successfully replied to, under other phases of feeling, or caution, or suspicion. Pride of opinion, and of consistency, is as obstinate in the Indian as in the European mind, but is more difficult to conquer, in proportion as it is left in its original state of darkness, or error. Even where Christianity has apparently given new grounds to hope, and modified its original views of life, if not radically changed them, there is still a bias in favor of these superstitious rites, which is very perceptible.

Citations: