Characteristic traits, in the history of races, often develop themselves in connection with the general or local features of a country, or even with some minor object in its natural history. There is a remarkable instance of this development of aboriginal mind in the history of the Oneidas.

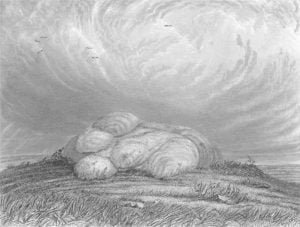

This tribe derives its name from a celebrated stone, (a view of which is annexed) which lies partly imbedded in the soil, on one of the highest eminences in the territory formerly occupied by that tribe, in Western New York. This ancient and long-remembered object in the surface geology of the country, belongs to the erratic-block group, and has never been touched by the hand of the sculptor or engraver. It is indissolubly associated with their early history and origin, and is spoken of, in their traditions, as if it were the Palladium of their liberties, and the symbolical record of their very nationality. Unlike the statue of Pallas, which fell from heaven, and upon which the preservation of Troy was believed to depend, the Oneida Stone was never supported by so imaginative a theory, but, like the Trojan statue, it was identified with their safety, their origin, and their name. It was the silent witness of their first association as a tribe. Around it their sachems sat in solemn council. Around it, their warriors marched in martial file, before setting out on the warpath, and it was here that they recited their warlike deeds, and uttered their shouts of defiance. From this eminence they watched, as an eagle from her eyrie, the first approaches of an enemy; and to this spot they rushed in alarm, and lit up their beacon-fires to arouse their warriors, whenever they received news of hostile footsteps in their land. They were called Oneidas, from Oneöta, the name of this stone, the original word, as still preserved by the tribe, which signifies the People of the Stone, or, by a metaphor, the People who sprang from the Stone. A stone was the symbol of their collective nationality, although the tribe was composed, like the other Iroquois cantons, of individuals of the clans of the Turtle, the Bear, and the Wolf, and other totemic bearings. They were early renowned, among the tribes, for their wisdom in council, bravery in war, and skill in hunting; and it is yet remembered that, when the Adirondack and other enemies found their trail and foot marks in the forest, they fled in fear, exclaiming, “It is the track of the Oneida!” To note this discovery, it was customary with the enemy to cut down a sapling to within two or three feet of the ground, and peel its bark cleanly off, so as to present a white surface to attract notice. They then laid a stone on the top. This was the well-known symbol of the Oneida, and was used as a warning to the absent members of the scouting party who might fall on the same trail.

The frequent allusion to the Oneida Stone in old writers upon the Indian customs, and its absolute Palladic value in their history, induced me to visit it, with Oneida guides, in the summer of 1845, and it is the fact of this visit that leads me to offer this brief notice of it.

I found the stone to be a boulder of syenite, imbedded firmly in the drift stratum, upon the apex of one of the most elevated Yonondas or hills in that part of the country. Its composition is feldspar, quartz, and hornblende, with some traces of an apparently epedotic mineral, in which respects it resembles (mineralogically) the very barren character of the northern syenites. Its shape is irregularly orbicular, and its surface bears evident marks of that species of abrasion common to primary boulders which are found at considerable distances from their parent beds. It is a peculiarity that its surface appears, minutely considered, to be rougher than is often found in remotely drifted blocks of this class of rocks, which may, perhaps, be the result of ancient fires kindled against its sides. That no such fires have, however, been kindled for a very long period, is certain from the traditions of the tribe, who have had the seat of their council-fire at Konaloa, or Oneida Castle, ever since the discovery of New York by Hudson; and how much earlier, we know not. 1 On closely inspecting this stone, minute species of mosses are found to occupy asperities in its surface.

The original selection of the Oneida Stone for the object, to which it was consecrated by this tribe, was probably the result of accident. Or if we look to remote causes, it was the effect of that geological disturbance of the surface, which left the drift stratum on the very apex of the hill. This hill is the highest prospect-point in the country. It was the natural spot for a beacon-fire. The view from it is magnificent. From its top the most distant objects can be seen, and a fire raised on this eminence, would act as a warning to their hunters and warriors over an immense area east and west, north and south. It is the highest hill of a remarkable system of hills, which may be called the Oneota Group, ranging through the counties of Oneida, Madison, and Sullivan, which throws its waters by the Oriskany, the Oneida, and various outlets into the Atlantic through the widely diverging valleys of the St. Lawrence, the Hudson, and the Susquehanna. It would be interesting to know its elevation above the ocean, in order to show its relation to the leading mountain groups of New York, and give accuracy to our interior topography; an object, it may be said, which can never be attained without carrying a line of accurate heights and distances over the entire interior of the State.

It is one of the peculiar features of this hill of the Oneida or Oneota Stone, that its apex shelters from the north-east winds the worst winds of our continent a fertile transverse valley, which was originally covered with groves of butternut and other nut wood, having a spring of pure water, which gathers into a pool, and wends its way down the valley in a clear brook. In this warm valley, the Oneidas originally settled. Here they raised their corn from time immemorial the woods abounded with the deer and bear, and smaller species of game. The surrounding brooks and lakes gave them fish, and they appear to have availed themselves of the first introduction of the apple into the continent, to carry its seed to these remote and elevated valleys, in which their orchards, on the settlement of the country, were found to cover miles of territory.

At the site of the spring in the valley, there was also found a remarkable stone a block rather than a boulder, consisting of a compact grayish white carbonate of lime, which, from the little evidences of abrasion it bears, could not have been transported by geological causes, far from its parent bed. This white stone at the spring has sometimes been called the Oneida Stone; but I was assured, in repeated instances, by Oneidas, and by residents conversant with the Oneida traditions, that the syenite boulder on the apex of the hill is the true stone, which the tribe regards as their ancient tribal monument.

I observed other boulders of various character on other parts of the hill, chiefly on its eastern declivities, all of which were of moderate size, and bore more or less evidence of the drift abrasion. Nothing, indeed, in the natural history of the country, presents a more interesting subject of study than the Oneida drift stratum, which covers, as a part of its range, this elevated area of hills. We see here, along with the various forms of the sandstones, limestones, and grits, peculiar to the state, and the cornutiferous lime-rock and silicious slates of more distant parts, scattered along with pebbles of opaque and iron-colored quartz, granites, and porphyries. The origin and direction of this drift is a subject of considerable geological moment. Many of these boulders belong to the saline group of the sandstone system; a group of rocks which develops itself west of the sources of the River Mohawk and the Stanwix Summit; reaching, at some points, to the shores of Lake Ontario, and the inferior strata of the Genesee and Niagara Rivers. In searching for the direction of this drift, it may be well to look in the same general course, although we have not, I believe, any known beds of granites and syenites in place, in a north-easterly direction, till we reach the region of the ancient Cateracqua, the Kingston of modern days; and the Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence River. Turning north-westwardly, we find no syenite in place till we reach the barren, desolate track, which interposes between the north shores of Lake Huron and the southeastern margin of Lake Superior. But the syenites of that region, as developed in the range between Gros Cape and Gargontwau, are more highly crystalline. The same superior degree of crystallization is observed in the remarkable knobs of syenite, which rise, in place, through the prairie soil of the Upper Mississippi, at the Peace Rock, above St. Anthony’s Falls; a spot reached by the United States Interior Exploring Expedition of 1820, on the 28th of July. 2

Among the boulders of the Oneida drift covering this eminence, I observed a small, column-shaped, black rock, standing in the soil, which had so completely the aspect of the black Egyptian marble from the Nile, that, for a moment, I fancied a trace of a similar silico-argillaceous stratum had been found in America. The illusion was sustained by a similar infusion of yellowish coloring matter. A fresh feature, however, instantly undeceived me, and disclosed a comparatively soft, argillaceous, sedimentary block, veined with a yellowish oxide, which, lying at a comparatively high altitude, and exposed to fierce winds from the north-east, had assumed an exterior color and semi-polish quite remarkable.

But without attempting to trace these boulders to their primary sources in the geological system, there can be little question, from general observation, that the direction of the Oneida drift is towards the southwest. In this respect it differs but little from, if it does not quite correspond with, the general direction of the Massachusetts and New England drift, as observed by Dr. Hitchcock. 3 Such is the uniform course of the drift observed here, in positions where the force of the movement has not been disturbed by leading valleys crossing its course; such as are presented by the Mohawk below the Astorenga, or Little Falls, or by the Hudson Valley below the Highlands. In the former case, the heavy blocks of debris have been carried nearly due east; and in the latter, directly south.

These suggestions will denote the position of the Oneida Stone as a member of the erratic block group; but I do not desire to merge its historical and antiquarian interest in the consideration of its natural history. It is to the tribal origin, history, and character of the Oneidas themselves, that this monument is suited to bear its most important testimony. Ancient changes in the earth s surface have manifestly placed it here; but as a memento of such mutations, it is not more interesting than thou sands and millions of tons of the primary and sedimentary drift which have been pressed onward and spread, broad-cast, by a mighty force, over this part of the State. But of all these thousands and millions of tons of drifted and scattered rock which mark the surface of the northern Atlantic States, nay, of the whole continent, this block alone, so far as we know, has been selected by one of the aboriginal tribes as the symbol of their compact. Piles of loose, small stones, such as that of Ochquaga, have been gathered in remembrance of a battle or an heroic act. Mounds of earth, whose origin and purport have been strangely mystified, have been piled up as objects to designate places of sepulture, of sacrifice, and of worship. Carved shells and wampum belts have been exchanged to perpetuate the sanctity of treaties and covenants among a people without letters. But this alone stands on this continent as the simple monument of a nation s origin, power, and name. This alone tells the story of a people’s rise; and if we are careful of the fame of a brave and worthy people, who fought for us in our struggle for liberty, it will for ages carry their memory on to posterity.

No person can stand on this height, and survey the wide prospect of cultivation and the elements of high agricultural and moral civilization, which it now presents, without sensations of the most elevated and pleasurable kind. On every side there stretches out long vistas of farms, villages, and spires, the lively evidences of a high state of manufacturing and industrial affluence. The plough has carried its triumphs to the loftiest summit; and the very apex on which the locality of the monument, which is the subject of this paper, rests, was covered, at the time of my visit, with luxuriant fields of waving grain. Least of all, can the observer view this rich scene of industrial opulence, without calling to mind that once proud and indomitable race of hunters and warriors, whose name the country bears. That name has become, indeed, their best monument quadruply borne, as it is, by a broad county a spacious and beautiful lake a rich stream and valley, and a thriving village, which marks the site of the ancient castle. But all that marked the aboriginal state of the Oneida prosperity and power has passed away. Their independence, their pride, their warfare, the objects of their highest ambition and fondest hope, were mistaken, and were destined to fall before the footsteps of civilization. Even they themselves have submitted to the truths of a higher and better ambition. Many of their numbers have taken shelter in the distant valleys of Wisconsin. A portion of the tribe has joined the Iroquois settlements in Canada: in both which positions, however, they are no longer hunters and warriors, but farmers, mechanics, and Christians. The remnant who linger in their beloved valley, have almost entirely conformed to the high state of industry and morals around them. Their only ambition now is the school, the church, the farm, and the workshop. Not a single trace of paganism is left. Not a single member of their compact and industrial community is known, who is not a temperate man. Education and industry have performed their usual offices; and the State of New York, by a noble magnanimity, and welcome of race, worthy of her early and uniform history and character, has, it is believed, within late years extended over them the broad shield of her protective laws, her school system, and her peculiar and enlarged type of social liberality.

Citations:

- By counting the cortical layers of a black walnut tree, growing in an ancient corn-field near the Stone, the place must have been abandoned about A. D. 1550 fifty-nine years before Hudson’s discovery. Notes on the Iroquois, page 52, Legis, Doc., N. Y.[

]

- Narrative Journal of an Expedition to the Sources of the Mississippi, 1820. Albany, 1821; 1 vol. 8vo.[

]

- Vide his Geological Report.[

]