The sacred beliefs of these Indians are largely formulated and expressed in sayings and narratives having some resemblance to the legends of European peoples. There are available large collections of these tales and myths from the Blackfoot, Crow, Nez Perce, Assiniboin, Gros Ventre, Arapaho, Arikara, Pawnee, Omaha, Northern Shoshoni, and less complete series from the Dakota, Cheyenne, and Ute. In these will be found much curious and interesting information. Each tribe in this area has its own individual beliefs and sacred myths, yet many have much in common, the distribution of the various incidents therein forming one of the important problems in anthropology.

Mythology of the Plains Indians

A deluge myth is almost universal in the Plains and very widely distributed in the wooded areas as well. Almost everywhere it takes the form of having the submerged earth restored by a more or less human being who sends down a diving bird or animal to obtain a little mud or sand. Of other tales found both within and without the Plains area we may mention, the “Twin-heroes,” the Woman who married a star and bore a Hero,” and the “Woman who married a Dog.” Working out the distribution of such myths is one of the fascinating tasks of the folklorist and will some time give us a clearer insight into the prehistoric cultural contacts of the several tribes. A typical study of this kind by Dr. R. H. Lowie will be found in the Journal of American Folk-Lore, September, 1908, where, for example, the star-born hero is traced through the Crow, Pawnee, Dakota, Arapaho, Kiowa, Gros Ventre, and Blackfoot. Indian mythologies often contain large groups of tales each reciting the adventures of a distinguished mythical hero. In the Plains, as elsewhere, we find among these a peculiar character with supernatural attributes, who transforms and in some instances creates the world, who rights great wrongs, and corrects great evils, yet who often stoops to trivial and vulgar pranks. Among the Blackfoot, for instance, he appears under the name of Napiw a , white old man, or old man of the dawn. He is distinctly human in form and name. The Gros Ventre, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Hidatsa, and Mandan seem to have a similar character in their mythology.

The uniqueness of the White-old-man appears when we consider the mythologies of the adjoining culture areas. Thus between the Plains and the Pacific Ocean similar tales appear, but are there attributed to an animal character with the name and attributes of a coyote. Under this name he appears among the Crow, Nez Perce, and Shoshoni, on the western fringe of the Plains, but rarely among the Pawnee, Arikara, and Dakota and practically never among the tribes designating him as human. Again among the Assiniboin, Dakota, and Omaha, this hero is given a spider like character (Unktomi). It is thus clear that while the border tribes of the Plains, in common with many other parts of the continent, have an analogous series of tales attributed to animal characters, the tendency at the center is to refer the same tales to a human character. Curiously enough, the names for this character all have in common the ideas of white and east and were automatically applied to Europeans when first encountered. For these reasons, if no other, the occurrence of a human trickster hero appears as one of the most distinctive characteristics of Plains culture.

Irrespective of the preceding hero cycle, many animal tales are to be found in the Plains. Among these, as in most every part of the world, we find curious ways of explaining the structural peculiarities of animals as due to some accident; for example, the Blackfoot trickster in a rage tried to pull the lynx asunder whence that animal now has a long body and awkward legs. Such explanations abound in all classes of myths and are considered primary and secondary according to whether they directly explain the present phenomena as in the case of the lynx, or simply narrate an anecdote in which the transformation is a mere incident. Occasionally, one meets with a tale at whose ending the listener is abruptly told that thenceforth things were ordered so and so, the logical connection not being apparent. Probably what happens here is that the native author knowing it to be customary to explain similar phenomena by mythical occurrences, rather crudely adds the explanation to a current tale. However, not all the animal tales of the Plains function as explanations of origin and transformation, for there are tales in which supernatural beings appear in the form of well-known animals and assist or grant favors to human beings. The buffalo is a favorite character and is seldom en countered in the mythology from other areas. The bear, beaver, elk, eagle, owl, and snake are frequently referred to but also occur in the myths of Woodland and other tribes. Of imaginary creatures the most conspicuous are the water monster and the thunderbird. The former is usually an immense horned serpent who keeps under water and who fears the thunder. The thunder-bird is an eagle-like being who causes thunder.

Migration Legends of the Plains Indians

Those accounting for the origins and forms of tribal beliefs and institutions make up a large portion of the mythology for the respective tribes and must be carefully considered in formulating a concept of the religion and philosophy of each.

Religious Concepts of the Plains Indians

To most of us the mention of religion brings to mind notions of God, a supreme over ruling and decidedly personal being. Nothing just like this is found among the Indians. Yet, they seem to have formulated rather complex and abstract notions of a controlling power or series of powers pervading the universe. Thus, the Dakota use a term wakan tanka which seems to mean, the greatest sacred ones. The term has often been rendered as the great mystery but that is not quite correct. It is true that anything strange and mysterious is pronounced wakan, or as having attributes analogous to wakan tanka; but this seems to mean supernatural. The fact is, as demonstrated by Dr. J. R. Walker, that the Dakota do recognize a kind of hierarchy in which the Sun stands first, or as one of the wakan tanka. Of almost equal rank is the Sky, the Earth, and the Rock. Next in order is another group of four, the Moon (female), Winged-one, Wind and the “Mediator” (female). Then come inferior beings, the buffalo, bear, the four winds and the whirl wind; then come four classes or groups of beings and so on in almost bewildering complexity. So far as we know, no other Plains tribe has worked out quite so complex a conception. The Omaha wakonda is in a way like the Dakota wakan tanka. The Pawnee recognized a dominating power spoken of as tirawa, or, ” father,” under whom were the heavenly bodies, the winds, the thunder, lightning, and rain; but they also recognized a sacred quality, or presence, in the phenomena of the world, spoken of as kawaharu, a term whose meaning closely parallels the Dakota wakan. The Blackfoot resolved the phenomena of the universe into “powers” the greatest and most universal of which is natosiwa, or sun power. The sun was in a way a personal god having the moon for his wife and the morning-star for his son. Unfortunately, we lack data for most tribes, this being a point peculiarly difficult to investigate. One thing, however, is suggested. There is tendency here to conceive of some all-pervading force or element in the universe that emanates from an indefinite source to which a special name is given, which in turn becomes an attribute applicable to each and every manifestation of this conceivably divine element. Probably nowhere, not even among the Dakota, is there a clear cut formulation of a definite god-like being with definite powers and functions.

A Supernatural Helper

It is much easier, how ever, to gather reliable data on religious activities or the functioning of these beliefs in actual life. In the Plains, as well as in some other parts of the continent, the ideal is for all males to establish some kind of direct relation with this divine element or power. The idea is that if one follows the proper formula, the power will appear in some human or animal form and will form a compact with the applicant for his good fortune during life. The procedure is usually for a youth to put himself in the hands of a priest, or shaman, who instructs him and requires him to fast and pray alone in some secluded spot until the vision or dream is obtained. In the Plains such an experience results in the conferring of one or more songs, the laying on of certain curious formal taboos, and of the designation of some object, as a feather, skin, shell, etc., to be carried and used as a charm or medicine bundle. This procedure has been definitely reported for the Sarsi, Plains-Cree, Blackfoot, Gros Ventre, Crow, Hidatsa, Mandan, Dakota, Assiniboin, Omaha, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Pawnee. It is probably universal except perhaps among the Ute , Shoshoni, and Nez Perce. We know also that it is frequent among the Woodland Cree, Menomini, and Ojibway. Aside from hunger and thirst, there was no self torture except among the Dakota and possibly a few others of Siouan stock. With these it was the rule for all desiring to become shamans, or those in close rapport with the divine element, to thrust skewers through the skin and tie themselves up as in the sun dance, to be discussed later.

Now, when a Blackfoot, a Dakota, or an Omaha went out to fast and pray for a revelation, he called upon all the recognized mythical creatures, the heavenly bodies, and all in the earth and in the waters, which is consistent with the conceptions of an illy localized power or element manifest everywhere. No doubt this applies equally to all the aforesaid tribes. If this divine element spoke through a hawk, for example, the applicant would then look upon that bird as the localization or medium for it; and for him, wakonda, or what not, was manifest or resided therein; but, of course, not exclusively. Quite likely, he would keep in a bundle the skin or feathers of a hawk that the divine presence might- ever be at hand. This is why the warriors of the Plains carried such charms into battle and looked to them for aid. It is not far wrong to say that all religious ceremonies and practices (all the so-called medicines of the Plains Indians) originate and receive their sanction in dreams or induced visions, all, in short, handed down directly by this wonderful vitalizing element.

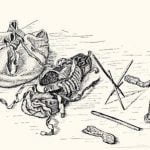

Medicine Bundles

In anthropological literature it is the custom to use the term medicine in a technical sense, meaning anything that manifests the divine element. Among the Blackfoot, Arapaho, Crow, Kiowa, Hidatsa, and Mandan especially and to varying extent among the other tribes of the Plains, the men made extraordinary use of these charms or amulets, which were, after all, little medicine bundles. A man rarely went to war or engaged in any serious undertaking with out carrying and appealing to one or more of these small bundles. They usually originated, as just stated, in the dreams or visions of so-called medicine men who gave them out for fees. With them were often one or more songs and a formula of some kind. Examples of these may be seen in the Museum s Pawnee and Blackfoot collections, where they seem most highly developed.

In addition to these many small individual and more or less personal medicines, many tribes have more pretentious bundles of sacred objects which are seldom opened and never used except in connection with certain solemn ceremonies. We refer to such as the tribal bundles of the Pawnee, the medicine arrows of the Cheyenne, the sacred pipe and the wheel of the Arapaho, the “taimay” image of the Kiowa, the Okipa drums of the Mandan, and the buffalo calf pipe of the Dakota. In addition to these very famous ones, there are numerous similar bundles owned by individuals, especially among the Blackfoot, Sarsi, Gros Ventre, Omaha, Hidatsa, and Pawnee. The best known type of bundle is the medicine-pipe which is highly developed among the Blackfoot and their immediate neighbors. In the early literature of the area frequent reference is made to the calumet, or in this case, a pair of pipestems waved in the demonstration of a ritual binding the participants in a firm brotherhood.

This ceremony is reported among the Pawnee, Omaha, Ponca, Mandan, and Dakota, and according to tradition, originated with the Pawnee. The use of either type of pipe bundle seems not to have reached the western tribes. One singular thing is that in all these medicine-pipes, it is the stem that is sacred, often it is not even perforated, is frequently without a bowl, and in any event rarely actually smoked. It is thus clear that the whole is highly symbolic.

The war bundles of the Osage have not been investigated but seem to belong to a type widely distributed among the Pawnee, Sauk and Fox, Menominie, and Winnebago of the Woodland area. Among the Black-foot, there is a special development of the bundle scheme in that they recognize the transferring of bundles and amulets to other persons together with the compact between the original owner and the divine element. The one receiving the bundle pays a handsome sum to the former owner. This buying and selling of medicines is so frequent that many men have at one time and another owned all the types of bundles in the tribe.

The greatest bundle development, however, seems to rest with the Pawnee, one of the less typical Plains tribes, whose whole tribal organization is expressed in bundle rituals and their relations to each other. For example, the Skidi Pawnee, the tribal division best known, base their religious and governmental authority upon a series of bundles at the head of which is the Eveningstar bundle. The ritual of this bundle recites the order and purpose of the Creation and is called upon to initiate and authorize every important under taking. The most sacred object in this bundle is an ear of corn, spoken of as Mother and symbolizing the life of man. Similar ears are found in all the important bundles of the Pawnee and one such ear was carried by a war party for use in the observances of the warpath. From all this we see that the emphasis of Pawnee thought and religious feeling is placed upon cultivated plants in contrast to the more typical Plains tribes who make no attempts at agriculture, but who put the chief stress upon buffalo ceremonies. The tendency to surround the growing of maize with elaborate ceremonies is characteristic of the Pueblo Indians of the Southwest and also of such tribes east of the Mississippi as made a specialty of agriculture.

In the Museum collections are a few important bundles, a medicine-pipe, and a sun dance bundle (natoas) from the Blackfoot, the latter a very sacred thing; an Arapaho bundle; the sacred image used in the Crow sun dance; an Osage war bundle; a series of tribal bundles from the Pawnee, etc. To them the reader is referred for further details.