The men of the Plains were not elaborately clothed. At home, they usually went about in breech-cloth and moccasins. The former was a broad strip of cloth drawn up between the legs and passed under the belt both behind and before. There is some reason for believing that even this was introduced by white traders, the more primitive form being a small apron of dressed skin. At all seasons a man kept at hand a soft tanned buffalo robe in which he tastefully swathed his person when appearing in public. This was universally true of all, with the possible exception of some southern tribes. In the Plateau area, the most common for winter were robes of antelope, elk, and mountain sheep, while in summer elkskins without the hair were worn. Beaver skins and those of other small animals were sometimes pieced together. According to Grinnell, the Blackfoot, east of the Rocky Mountains, also used these various forms of robes. Again, the Plateau tribes sometimes used a curious woven blanket of strips of rabbitskin also widely used in Canada and the Southwest. So far this type of blanket has not been reported for the Plains tribes east of the mountains.

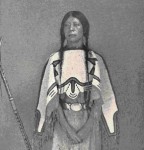

Some of the most conspicuous objects in the collections are the so-called war, or scalp shirts, Fig. 12. One of the oldest was obtained by Col. Sword in 1838 and seems to be Dakota (Sioux). It is of deerskin: Some fine examples are credited to the Teton-Dakota, Crow, and Blackfoot, though almost every tribe had them in late years. This type, however, should not be taken as a regular costume. Though in quite recent years it has become a kind of tuxedo, it was formerly the more or less exclusive uniform of important functionaries. On the other hand, the shirt itself, stripped of its ornaments and accessories seems to be of the precise pattern once worn in daily routine. Yet, the indications are that as a regular costume, the shirt was by no means in general use. The Cree, Dene, and other tribes of central Canada wore leather shirts, no doubt because of the severe winters. We also have positive knowledge of their early use by the Blackfoot, Assiniboin, Crow, Dakota, Plains-Cree, Nez Perce, Northern Shoshoni, Gros Ventre, and on the other hand of their absence among the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Pawnee, Osage, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Comanche. Thus, the common shirt was after all not typical of the Plains Indians: it is only recently that the special decorated .form so characteristic of the Assiniboin, Crow, Blackfoot, and Dakota has come into general use. Several interesting points may be noted in the detailed structure of these shirts, but we must pass on. For the head there was no special covering. Yet in winter the Blackfoot, Plains-Cree, and perhaps others in the north, often wore fur caps. In the south and west the head was bare, but the eyes were sometimes protected by simple shades of rawhide. So, in general, both sexes in the Plains went bare-headed, though the robe was often pulled up forming a kind of temporary hood.

Mittens and gloves seem to have been introduced by the whites, though they appear to have been native in other parts of the continent.

Moccasin

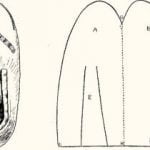

That part of the pattern marked a forms the upper side of the moccasin; 6, the sole; e, the tongue; f, the trailer. The leather is folded lengthwise, along the dotted line, the points c and d are brought together and the edges sewed along to the point g, which makes a seam the whole length of the foot and around the toes. The vertical heel seam is formed by sewing c and d now joined to h, f projecting. The strips c and d are each, half the width of that marked h, consequently the side seam at the heel is half way between the top of the moccasin and the sole, but reaches the level at the toes. As the sides of this moccasin are not high enough for the wearer s comfort, an extension or ankle flap is sewed on, varying from two to six inches in width, cut long enough to overlap in front and held in place by means of the usual drawstring or lacing around the ankle.

Everywhere, we find no differences between the robes of men and women except in their decorations. The buffalo robes were usually the entire skins with the tail. Among most tribes, this robe was worn horizon tally with the tail on the right hand side. Light, durable, and gaily colored blankets were later introduced by traders and are even now in general use.

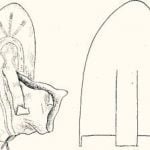

Moccasins were worn by all, the sandals of the Southwest and Mexico not being credited to these Indians. The two general structural types of moccasins in North America are the one-piece, or soft-soled moccasin, and the two-piece, or hard-soled. The latter prevails among these Indians, while the former is general among forest Indians. A Blackfoot moccasin of a simple two-piece pattern is shown in Fig. 11. The upper is made of soft tanned skin and after finishing and decorating is sewed to a rawhide sole cut to fit the foot of the wearer. A top, or vamp, may be added.

The pattern for a Blackfoot one-piece moccasin is shown in Fig. 10. Our collections show that this type occurs occasionally among the Sarsi, Blackfoot, Plains-Cree, Assiniboin, Gros Ventre, Northern Shoshoni, Omaha, Pawnee, and Eastern Dakota. So far, it has not been reported for any of the southern tribes. Among many of the foregoing, this form seems to have been preferred for winter wear, using buffalo skin with the hair inside. Again, since all the tribes to the north and east of these Indians used the one-piece moccasin all the year round, its presence in this part of the Plains is quite natural.

To the south, we find a combined stiff-soled moccasin and legging to be seen among the Arapaho, Ute, and Comanche. This again seems to be related to a boot type of moccasin found in parts of the Southwest.

So, in general, the hard-soled moccasin is the type for these Indians. Old frontiersmen claim that from the tracks of a war party, the tribe could be determined; this is in a measure true, for each had some distinguishing secondary feature, such as heel fringes, toe forms, etc., that left their marks in the dust of the trail. Ornaments and decoration will, however, be discussed under another head.

Almost everywhere the men wore long leggings tied to the belt. Women s leggings were short, extending from the ankle to the knee and supported by garters.

Women’s Clothing

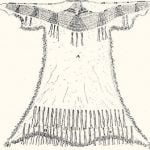

The women of all tribes wore more clothing than the men. The most typical garment was the sleeveless dress, a one-piece garment, an excellent example of which is to be seen in the Audubon collection, Fig. 14.

This type was used by the Hidatsa, Mandan, Crow, Dakota, Arapaho, Ute, Kiowa, Comanche, Sarsi, Gros Ventre, Assiniboin, and perhaps others. A slight variant is reported for the Nez Perce, Northern Shoshoni, and Plains-Cree in that the extensions of the cape are formed into a tight-fitting sleeve. Some writers claim that in early days the Assiniboin and Blackfoot women also used this form. Formerly, the Cheyenne, Osage, and Pawnee women wore a two-piece garment consisting of a skirt and a cape, a form typical of the Woodland Indians of the east.

A close study of Plains costumes will disclose that in spite of one general pattern, there are tribal styles. In the first place, all dresses show the same main outline, curious open hanging sleeves, and a bottom of four appendages of which those at the sides are longest (Fig. 14). Almost without exception these dresses are made of two elkskins, the natural contour of which is shown in Fig. 15. The sewing of these together gives the pattern of the garment, which is modified by trimming or piecing the edges as the tribal style may require. This is a particularly good example of how the form of a costume may be determined by the material. The distribution of tribal variations in these dress patterns is shown in Fig. 16.

The shirts for men are also made of two deerskins on a slightly different pattern, but one in which the natural contour of the skin is the determining factor.

The manner of dressing the hair is often a conspicuous conventional feature. Many of the Plains tribes wore it uncropped. Among the northern tribes the men frequently gathered the hair in two braids but in the extreme west and among some of the southern tribes, both sexes usually wore it loose on the shoulders and back.

Hair

The Crow men sometimes cropped the forelock and trained it to stand erect; the Blackfoot, Assiniboin, Yankton-Dakota, Hidatsa, Mandan, Arikara, and Kiowa trained a forelock to hang down over the nose. Early writers report a general practice of artificially lengthening men s hair by gumming on extra strands until it sometimes dragged on the ground.

The hair of women throughout the Plains was usually worn in the two-braid fashion with the median part from the forehead to the neck. Old women frequently allowed the hair to hang down at the sides or confined it by a simple headband.

Again, we find exceptions in that the Oto, Osage, Pawnee, and Omaha closely cropped the sides of the head, leaving a ridge or tuft across the crown and down behind. It is almost certain that the Ponca once followed the same style and there is a tradition among the Ogallala division of the Teton-Dakota that they also shaved the sides of the head. (See also History of the Expedition of Lewis and Clark, Reprinted, New York, 1902, Vol. 1, p. 135.) We may say then that the love of long heavy tresses was a typical trait of the Plains.

By the public every Indian is expected to have his hair thickly decked with feathers. The striking feather bonnets with long tails usually seen in pictures were exceptional and formerly permitted only to a few distinguished men. They are most characteristic of the Dakota. Even a common eagle feather in the hair of a Dakota had some military significance according to its form and position. On the other hand, objects tied in a Blackfoot s hair were almost certain to have a charm value. So far as we know, among all tribes, objects placed in the hair of men usually had more than a mere aesthetic significance.

Hair Accessories

Beads for the neck, ear ornaments, necklaces of claws, scarfs of otter and other fur, etc., were in general use. The face and exposed parts of the body were usually painted and sometimes the hair also. Women were fond of tracing the part line with vermilion. There was little tattooing and noses were seldom pierced. The ears, on the other hand, were usually perforated and adorned with pendants which among Dakota women were often long strings of shells reaching the waist line.

Instead of combs, brushes made from the tails of porcupines were used in dressing the hair. The most common form was made by stretching the porcupine tail over a stick of wood. The hair of the face and others parts of the body was pulled out by small tweezers.