No section of country in the United States combines a greater variety of inland scenery than that occupied by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, embracing portions of the counties of Cherokee, Graham, Jackson, and Swain, in southwestern North Carolina. Nestled between the Blue Ridge on the east and the Smoky mountains on the west, partially sheltered by sharp ranges and lofty peaks exceeding Mount Washington in height, and more than 2,000 feet above sea level, the “Qualla boundary”, as it is styled, represents the home locality of 1,520 Cherokee Indians. Swift streams, which abound in speckled trout, wind about all points of the compass for their final outlet, leaving at almost every change of course some fringing skirt of mellow land well suited for farm or garden purposes. Choice timber, ample for all uses for many years, is found throughout the entire region. Strawberries, blackberries, grapes, and wild fruits are abundant in their season, and the peach and apple generously respond to moderate care. The corn crop rarely fails. The potato is prolific in bearing and excellent in quality. Wheat, rye, and oats are cultivated with moderate returns, but sufficient, as a rule, for the population, while melons and all garden products do well. Creeks and small streams and springs are so numerous and ample in flow that the simplest diversion of the water is sufficient for the irrigation of the most reluctant soil. The hay crop is limited by the small meadow area, so that corn husks are the main reliance for stock fodder. The almost universal use of a single steer for plowing and general farming purposes is because of the character of the land, which is made up of steep hillsides and narrow valley strips. Agricultural implements are of the simplest kind. As a suggestive fact, it is to be noticed that the fences are well built and well maintained throughout the farming tracts, even where the most primitive methods of farming prevail. The principal roads, with easy grades, good drainage, and free from abrupt or dangerous inclines, skirt mountain sides or follow water courses. Single trails, that often diverge to cabins which lie among the mountains or on their slopes, are only accessible on foot or in the saddle; but the chief thoroughfares show good judgment and skillful engineering to meet the difficulties which had to be surmounted. Some of these roads are better within the Indian district than over the approaches to or through the settlements of the white people. The houses are nearly all ” block houses “, a few only being log houses, rarely baying a second room, unless it be an attic room for sleeping or storage purposes, and are without windows. Corncribs, stock sheds, and tobacco barns are of material similar to the houses, except where, as with corncribs, logs are used for better ventilation. Hinges are mainly of wood, and the stairs are constructed of pin poles, ladders, or inclined, slatted planks. Fireplaces are often supplemented by stoves, but there is at all times an abundance of pine knots and similar fuel for light, heat, and cooking. The climate is invigorating and healthful, but cases of pneumonia are frequent, duo to the rapid changes of temperature.

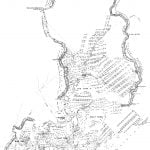

Surveys were made in 1875-1876 by M. S. Temple under the auspices of the United States land Office. These were embodied in a map published as “Map of the Qualla Indian reserve”. The term “reserve” is a misnomer, as the lauds so described were purchased for or by the Indians, and were not in any sense “reserved” for them by the United States. The map, however, is recognized by the federal courts in the adjudication of the conflicting claims of Indian and white settlers as a general basis of demarcation, but not as an exact definition of specific titles. The lines, except those surrounding the entire tract, are so entangled as to form a labyrinth of conflicting courses, which are inexplicable by surveyor, court, or jury. The Temple survey located “entries”. These, successively imposed, took slight notice of previous entries or, indeed, of occupation. The state of North Carolina received its fees and issued papers with little regard for records or files, a warning to those in search of permits to occupy lands within the country so inviting to incomers. A copy of the Temple map giving the numbers, as from time to time designated, is herewith furnished as a basis for the topographical map, which gives the present roads and the general occupation of the valleys. It also includes county lines. A. new survey, already initiated, will be essential to the settlement of existing conflicts of title and any exact definition of title hereafter. Reference will be made elsewhere to the issues involved in the pending survey.

A marginal map, on a reduced scale, indicates the relations of the 11 southwestern counties of North Carolina to each other and to the adjoining states of Georgia, South Carolina, and Tennessee, in each of which states the Cherokees once had lands and homes.

The practical center of interest and divergence in a visitation or description of the Cherokee country is found at the site of the United States agency and the adjoining training school at Cherokee, formerly known as Yellow hill. It is about 6 miles from Whittier, the nearest railroad and telegraph station, and 10 miles from Bryson city, formerly Charleston, the county seat of Swain. County. The Ocona Lufta River, which joins the Tuckasegee, a tributary of the Tennessee, less than 2 miles below Whittier, flows directly south along the school grounds, receiving its two principal tributary sources 2.5 miles to the north. The Bradley fork enters through white settlements near the house once the home of Abraham Enloe, which, by an absurd fiction, is associated with the old home of Abraham Lincoln. Ravens fork from the northeast is an impetuous stream, at times a torrent, flowing in its upper course through narrow valleys, coves or pockets, whose soil is rich, deep, and black, like that of the bottoms of the Miami and Scioto in Ohio. On Straight fork of this creek, at the very verge of the line of the Cathcart survey, in the last Indian house in that direction, lives Chitolski (Falling Blossom), a Cherokee of means and influence, whose name is expressive of the condition of the corn when the pollen, dropping into the silk, is supposed to bear some part in fertilizing the ear. His home is a new and spacious blockhouse, very comfortable, with the usual piazza in front. Upon accepting an invitation to dine, the water was, turned upon the wheel of the mill close by, and fresh meal was soon served in the shape of a hot ” corndodger “. ” Long sweetening ” of honey or molasses gave a peculiar sanction to a cup of good coffee, and this, with bacon and greens, supplemented with peaches grown on the farm, made a most excellent meal. This mill is one of many, alike simple in construction, where neighbors deposit their toll of grain, turn on the water, and grind their own meat Some of these mills have only a slight roof over the hopper and are open at the sides. Chitolski’s house is said to be one of the best in the country, and very few houses of the white people upon Indian lands or lands adjacent approach it in comfort. Some large peach trees were loaded with safely developed fruit, and a vigorous young orchard, carefully planted, gave promise of as prosperous a future as those of advanced growth, which bore the pledges of a good autumn product. A horse, several heifers, and chickens and ducks imparted life to the scene, and the host and his wife, whose grown children have sought independent homes, are preparing, with every indication of success, to spend their latter years in contentment and comfort. Chitolski is building a new path out from his snug valley “wide enough for wheels”, so that visitors will not be compelled to unhitch and mount harnessed horses to share his hospitality. Specimens of quartz and varieties of spar having suspicious yellow specs were produced and information sought as to their value. The washings of the streams give “gold color”, and some claim that they can net $1 a day when the water is low.

The whole trip to Big Cove, as this region is named, is attractive from its rich soil, its well-worked hillsides, its fertile coves between the mountain spurs, its excellent fences, and the universal indications of well-applied industry. A. sudden turn in the road brought in sight a happy boy fishing. He had succeeded in landing two fine speckled trout. The supply of trout at the proper season is abundant for table use. Eastward from the agency, crossing the Ocona Lufta river, below a substantial, elevated foot bridge aver the southern verge of Spray ridge and at the foot of Mount Hobbs, the panorama of the Soco valley, with its bright vista, is brought suddenly into view. Mountain spurs, carefully fenced gardens, well-lined furrows, and gleaming streams are distributed for 10 miles, until closed by the lofty Mount Dorchester, which, at the end of this valley, presents to the view an area of at least 30 miles. Descending from this point of outlook, the valley distance is varied by careful cultivation, with wheat and rye most conspicuous, while several strips of nearly a quartet’ of a mile in breadth are fenced with stone and irrigated by ditches, showing how resolutely the open spaces are utilized for substantial crops. At a distance of 5 miles the old mission house, long since abandoned for church purposes, still affords a popular gathering place for political and other meetings. At one of these meetings, during the enumeration, more than 100 Cherokees assembled to consult as to a change of their principal chief at the election in 1891, and to protest against any change in the management of their admirably conducted training school, The old building, open and dilapidated in front, is furnished with benches and desk, and the proceedings at the meeting alluded to were characterized by formality and good order.

Less than 1 mile further east, across the creek, is the spacious Soco schoolhouse. Excellent desks and accommodations greatly superior to those of some schoolhouses outside the, Indian lines distinguish this school, and the building is also used for church or Sunday school work on the Sabbath. It is a blockhouse, well hewn, closely jointed, and durable as well as convenient.

At the foot of Mount Dorchester, named in memory of a great admirer of the locality and warm supporter of the training school, and not more than 3 miles distant, one open tract of 30 acres is in good cultivation, while upon the hillsides, so steep that it seemed as if wings or ladders would be needed for tillage, several patches of from 6 to 10 acres were green with well-developed wheat, and on one of the slopes a “working bee” of 30 men, women, and children were uniting their forces to help a neighbor put in his corn. In places where even a single steer could not hold footing with the lightest plow a long line of willing workers hoed successive parallel seed trenches.

The Soco River enters this valley from the south at Oocomers mill, and at less than half a mile distant is the quaint, uncovered Washington mill, well patronized by the neighbors. Here Big Witch Creek joins the Soco, and by a rocky road or trail the cabin of Big Witch is reached. Big Witch is a genial, white-haired Cherokee, who, at the age of 105, was prompt to supply a chair and proud to speak of his great-great-grandchildren.

The Soco valley road is joined at the old mission house by a road from Webster and Whittier. At less than a mile a wagon trail leads to the house of Wesley Crow, a leading Cherokee councilman, who is one of the strongest supporters of the public schools. Penned in by abrupt mountains, at the head of one of the forks of Shoal creek, comfortably supplied with farm conveniences, industriously tilling wheat, corn, rye, and. potatoes, he points with great satisfaction to the loom and spinning wheel on his piazza as representing the industries of the household within. The absence of windows was no serious discomfort, as the inside comforts were all that he deemed desirable or necessary. He is a good representative man, steady, industrious, and interested in the welfare of the people. He has been one of the foremost of the Cherokee council in a movement to prevent the selection of Smith as principal chief at the election in 1891, maintaining that only a temperate man, of good moral character, and a friend of the public schools is lit for the place. Principal Chief Smith, a man of sufficient natural capacity to serve the people well, has borne the opposite character of late, although once very prominent. South from the trail leading to Crow’s house, as soon as the Indian lands are left, to the bridge across the Tuckasegee, at Whittier, both houses and roads are inferior to those upon the Indian lands, and the fences are poor. Immediately upon crossing the ford below the agency, and without ascending the summit that overlooks Soco valley, a road leads under the ridge, along the Ocona Lufta river, past the comfortable house and well-arranged barns of Vice Principal Chief John Going Welch, until it crosses Shoal creek, just above its union with the river. It then bears away, past the old agency headquarters, the deserted trading house of Thomas, past the residence of Rev. John Bird, a venerable, retired missionary, who long labored successfully among the Cherokees, and is still enthusiastic in their welfare, past the old site marked “Qualla” on the map, and leads off to Webster, the county town of Jackson. County, 14 miles distant. A second road from the Soco valley joins it at the old agency, where the broad, fertile tract of Enloe receives full sunlight and well repays culture. The road from the old mission also joins the Webster road near Qualla, and then turns southwest to Whittier. At the ford below the agency the Ocona Lufta, river suddenly turns eastward for a short distance, then as abruptly southward and westward, almost encircling Donaldson ridge, which faces the agency. Without crossing the ford, but passing directly under this ridge, the shortest road for Whittier gradually rises, crossing the foot of Mount Noble, and presents at its summit a view of a portion of the Ocona, Lufta valley, which is hardly surpassed by that of the Soco valley, the same principal peaks to the eastward having part in the landscape. This road descends westward, passing the old ‘Cite Sherrill homestead and the house of William P. Hyde, a mile from the agency, where it soon rejoins the river, bearing westward toward Bryson city. At the distance of 1.25 miles another dilapidated church stands, and in the center of the highway is a mammoth oak, where in midsummer the Indians gather for church and Sunday-school services in preference to the old church or the schoolhouse a little beyond. The old church is not wholly abandoned, however, the open sides seeming to be no special objection to those who habitually live with doors open for most of the year. A few hundred yards beyond the oak is located the Birdtown Indian schoolhouse. This also is a blockhouse, but has been weather boarded, and only needs paint to give it a modern dress. The peculiar Indian fancy for suggestive names has devised One for this unpretentious little building: an Indian boy, Willie Muttonhead, after hearing his Sunday-school teacher read the Bible description of the Pharisees, in the twenty-third chapter of Matthew, very promptly asked “if their schoolhouse wasn’t a hypocrite house “.

Less than a mile below the schoolhouse a rude road bears to the right, winds over and between hills near the source of Adams creek, passes the foot of the ascent upon which time new and spacious schoolhouse for the white people of Birdtown is located and the little Birdtown post office kept by Widow Keeler, and enters again the well-traveled road to Bryson city, about 4.5 miles from the agency, as indicated on the map. The most direct road to Whittier leaves this Bryson City road 3.5 miles from the agency, crosses the Ocona Lufta River and the Whittier summit, and then descends rapidly to the valley of the Tuckasegee. The home of William Ta-lah-lah, a prominent councilman, stands upon a hill to the right, shortly after passing Adams creek. All roads which border the numerous creeks are subject to rapid overflow in the rainy season or after heavy summer showers, and the streams become impassable. Simple bridges of hewn logs, often of great size, and guarded by hand rails, supply pedestrians the means of communication between the various settlements until the waters subside. In deep cuts; or where the Ocona Lufta River is thus crossed, substantial trestles or supports have been erected on each shore and in the stream, as no single tree would span the distance. Numerous short cuts or foot trails wind among the mountains and over very steep divides, but all the wagon roads for general travel have been indicated upon the map and described.. Wagon trails for hauling timber to single cabins or hamlets are not infrequent.

This somewhat minute description of the map is necessary for a true conception of the character of this people and their neighborly intercourse as of one great family. Their wants are few, They are peaceable, sociable, and industrious, without marked ambition-to acquire wealth, and without jealousy of their more prosperous neighbors.