At the last anniversary of Hampton, Secretary Schurz remarked in his speech “One day, soon, a very interesting sight will be seen here and at Carlisle. It will be the first Indian School-visiting Board. Within a few days twenty-five or thirty Sioux chiefs, among them some warriors whose hands were lifted against the United States but a few days ago, Red Cloud and others, will go to Carlisle and come here to see their children in these schools.”

Last May, accordingly, this “Indian School-visiting Board” reached Hampton. The meeting between them and their young relatives would have convinced the most skeptical that the heart of man answers to heart as face to face in water, whatever the skin it beats under

As the Gros Ventre and Ree chiefs gathered the children of their own tribes around them for a special talk, Son of the Star beckoned one of the older girls to the front, and searching some mysterious depths of his blanket, drew forth a dirty little coil of string about two feet long, unwound it, straightened it carefully, and let it hang from one hand to the floor, with the other outlining some little form about it, bringing quick-flitting smiles to the face of the girl, while the whole ring looked on with evidently intelligent interest, though not a word was spoken. Handing the string over to the girl, he dived into his blanket once more, producing this time a little worn pair of baby shoes. But at this his watcher broke down entirely in a flood of tender tears; for the whole silent pantomime had been a letter from home describing the growth and beauty of the little sister she had left winking in its cradle basket two years before.

Son of the Star was a fine specimen of an old chief of powerful proportions. Poor Wolf, in full Indian costume, and glory of porcupine quills and eagle feathers, had put a finishing touch to his dignity by an incongruous and ludicrously solemn pair of huge gold-bowed spectacles, which made him look like a caricature of Confucius.

The Gros Ventre were particularly anxious to see Ara-hotch-kish, the only son of their second chief, Hard Horn, who had been prevented by some accident from accompanying the expedition. They found the little fellow in the workshop painting pails, and pressed around him in an admiring group. Ara’s dignity was fully equal to the occasion. He worked away with an air of superb indifference, vouchsafing the old chiefs no notice whatever, except to elbow them aside, when his pail was done, to set it up and get down another, only aside glance now and then through his long lashes, and the shadow of a demure smile around his firm-set lips, betraying that he was taking in everything, and enjoying his honors.

All the chiefs were delighted spectators at the merry games of the evening “conversation hour.” In an evil moment, however, the 15-14-13 puzzle was explained to Confucius by some of his young Gros Venues, and he proved his common origin. with white humanity by succumbing instantly to its spell. For the rest of the evening his gold-bound goggles bent over the maddening squares as if they were the problem of his race, set, according to its white brethren’s favorite arrangement, with thirteen facts, fourteen experiments, and fifteen theories in hopeless reversion.

A visit from Bright Eyes, the eloquent young advocate of the Ponca, was a very powerful stimulus to the girls, as showing them what one of their own race and sex might become. After she left, one of the older girls said to me, with a pretty, timid hesitancy, “Miss Bright Eyes-I wish I like that.” Her own soft bright eyes shone with a soul in them as she added: “When I came to here, I feel bad all time; I want go home; I no want stay at Hampton. Now I want stay here. I not want go home. I want learn more, then go home, teacher my people.”

A few weeks after, on the visit of the chiefs from Dakota, this girl, at her own urgent request, stood up before the whole conclave and the school, and with flushed cheeks and downcast eyes told her people’s. rulers what the school was to her, and begged them to send all the children to learn the good road. Her speech, which, in order to reach all the chiefs, had to be translated by two interpreters, passing through English on the way, was listened to with respectful attention.

The most important result of Bright Eyes’s visit to the school was to rouse in her own heart the desire to make use of her hold upon public sympathy for he permanent benefit of her Indian sisters. With this desire she offered her services to speak at the East in behalf of a project of some Northern friends of the school to enlarge its work by erecting a building for Indian girls, to cost, complete and furnished, $15,000. A beautiful site adjoining the school premises, and now enclosed in them, was given as a generous send off by a lady friend. It will give room for the training of at least fifty more Indian girls at Hampton, thus effecting the desired balance of the sexes. The Secretary of the Interior has signified his readiness to send them from the agencies with the same appropriation as for the boys, of $150 per year apiece. There is every assurance of their readiness now to come. It is for the friends of the Indians to decide whether Hampton’s work for them shall be thus rounded and established, and the timid prayer be heard, “I wish I like that.”

Carlisle, Pennsylvania, like Hampton, Virginia, is classic ground in American history. Under the shade of its unbroken forests Benjamin Franklin met the red men in council. A British military post in the Revolution, and falling into the hands of the Continentals, the Hessian – built guard-house is still shown as once the place of Andro’s confinement, before his greater disaster.

The last and greatest change of fortune, which has filled the empty armories with ploughshares and pruning-hooks, and the soldiers’ quarters with a government school for Indian children-as if the spirit of the earliest and sacredest of Indian treaties still lingered in the groves of Penn–was brought about through a bill introduced in the winter of 1879 in the House of Representatives, entitled “A bill to increase educational privileges and establish additional industrial, training schools for the benefit of youth belonging to such nomadic Indian tribes as have educational treaty claims upon the United States. “It provided for the utilization for such school purposes of certain vacant military posts and barracks as long as not required for military occupation, and authorized the detail of army officers by the Secretary of War for service in such schools, without extra pay, under direction of the Secretary of the Interior.

The House Committee on Indian Affairs, in favorably reporting upon this bill, urged that the government had made treaty stipulations specially providing for education with nomadic tribes, including about seventy-one thousand Indians, having over twelve thousand children of school age; that the treaties were made in 1868, and in ten years less than one thousand children had received schooling. It was further urged that “the effort in this direction recently undertaken and in successful progress at the Industrial and Normal Institute of Hampton, Virginia, furnishes as striking proof of the natural aptitude and capacity of the rudest savages of the plains for mechanical scientific, and industrial education, when removed from parental and tribal surroundings and influences”; and that “the very considerable number of agents, teachers, missionaries, and others engaged in educational work who have visited and witnessed the methods of Hampton, join in commending them as just what the Indian needs, while the intercourse between the youth at Hampton and their parents has produced extraordinary interest and demand for educational help from these tribes.”

The importance of this measure was so recognized that even in anticipation of subsequent favorable action upon it by Congress, with a wise cutting of red tape, the “War Department turned over Carlisle Barracks to the Interior, and Captain Pratt was detailed to bring children from the Northern agencies before the frosts came, which would have delayed it another year. The transfer of the post was effected on the centennial anniversary of the battle of White Plains, eliciting from Secretary McCreary a felicitous remark upon the coincidence which on such memorial day gave up to Indian education a post for eighty years used as a training school for cavalry officers to make war chiefly upon Indians.

Taking with him Hampton’s godspeed, and two of his most advanced Dakota boys for interpreters and “specimens,” the captain started for Dakota in September, 1879, returning in a few weeks with eighty-four.

All but two of the St. Augustines from Hampton also accompanied their captain to Carlisle, to form a starting-point of English speech and civilization. One of these young men, a Kiowa, with a companion who had been under instruction at the North went on alone to Indian Territory in advance of Captain Pratt, and by their own influence they gathered forty-two children and youth from their own agency for Carlisle. These, with some more from other agencies in the Territory, were brought by the captain to the school and it opened with one hundred and forty-seven children on the 1st of November, 1879.

The President’s next Message and the report of the Secretary of the Interior again commended to public attention the importance of the -work at Hampton, with the new efforts to which its “promising results” had led at Carlisle and at Forest Grove, Oregon, where arrangements were made for a similar training at a white boarding-school of a number of Indian boys and girls belonging to tribes on the Pacific coast, under charge of Captain Wilkinson, who is making it quite successful under many difficulties.

Additions and changes from time to time have brought the number at Carlisle up to one hundred and ninety-six at the present time, fifty-seven of whom are girls. Besides the Sioux and St. Augustines, there are in lesser numbers other Cheyenne, Arrapaho, and Kiowa; also Comanche, Wichita, Seminole, Pawnees, Keechi, Towaconie, Nez Percés, and Ponca, from Indian Territory; Menomonee from Wisconsin; Iowas, Sacs, and Foxes from Nebraska; Pueblos from New Mexico; Lipan from old Mexico; to which will probably be added fifty Utes from Colorado, the first of the tribe ever in a school. Many of the number are children of chiefs or head-men; among others, of White Eagle, head chief of the Ponca; Black Crow, American Horse, and White Thunder, noted chiefs of the Sioux. The famous old chief Spotted Tail had four boys there and a daughter, with two more distant relatives, but, on his visit to them, took umbrage at finding his half-breed son-in-law no longer needed as interpreter, and went off in a huff, with all his little Spotted Tails behind him. For this hasty action he was called to account, immediately on his return, by his people, who could not understand why, if Carlisle was a bad place, he should not have brought their children away too, and on hearing the other side of the story from the chiefs who had accompanied him, asked to have him deposed for “double talking.” One of the indignant parents, with the mild name of Milk, in writing upon the subject to Captain Pratt, says, with some lactic acidity, “Spotted Tail has been to the Great Father’s house so often that he has learned to tell lies and deceive people.” It is pleasant to add that a judicious letting alone had the due effect, and he has requested the government’s permission to send his children back to Carlisle.

Many visitors go to Carlisle to see the Indians. Some of them, it must be acknowledged, are disappointed. After alighting at the commandant’s office, and being courteously received by Captain Pratt or one of his assistants, the spokesman of the party asks politely if they may “first look about by themselves a little.” Cordial permission given, they set forth, but in the course of half an hour are back again with clouded brows, and the appeal, “We thought we might see some Indians round; can you show us some?” A smile and a circular wave of the hand emphasize the assurance that a score or two of noble red men are within easy eye-range at the moment. Following the gesture with a glance over the green where the boys and girls are passing, perhaps, to their school-rooms, the shade of unsatisfaction deepens, and they explain: “Oh, but I mean real Indians. Haven’t you some real Indians– in blankets, you know, and feathers, and long hair?”

A little allowance must be made for sentiment in human nature, and if these easily disappointed visitors stay long enough they may be gratified with an occasional “real Indian” dance of a gentle type, or without much trouble the well-named maiden Pretty Day might be persuaded to attire herself, as becomes a high-born princess of the plains, in her cherished dress of finest dark blue blanket, embroidered deer-skin leggings, and curiously netted cape adorned with three hundred milk-white elk teeth, each pair of them the price of a pony.

Aboriginal picturesqueness is certainly sacrificed to a great extent in civilization. One who is willing to relinquish the idea, however, of a menagerie of wild creatures kept for exhibition, will not regret to find instead a school of neatly dressed boys and girls, with bright eyes and clean faces, as full of fun and frolic as if they were the descendants of the Puritans.

The barracks stand on a knoll half a mile from the town. From the upper piazza of the commandant’s quarters the eye sweeps over a beautiful landscape. Spurs of the Blue Ridge circle it in front and rear, from five to eight miles away, the old town lies down in the hollow, green fields stretch between, and the little “Tort Creek” winds its very tortuous way round the post grounds and through a grove of old trees. Beyond the flag-staff in front of the house is the parade-ground, where the boys drill and the girls play. A pretty sight it is to see the merry little crowd enjoying a game of ball, or with heads up and toes trying to turn out, taking off the boys’ “setting-up drill,” with shouts of laughter, finishing all up properly with the difficult achievement of touching fingers to toes without bending the knees.

Long brick buildings, ranged in a hollow square `with double sides, are variously occupied by schoolrooms and quarters for students and teachers, offices, dining room, kitchen, hospital, etc. The large stables of the garrison have been, for the most part, converted into workshops and a gymnasium. A little wooden chapel has been put up for the school, simply a long room, well lighted and furnished with settees but this has been all the building needed. So many substantial edifices, in tolerable order to start with, have been a great advantage. This is especially noticeable in the school building, two stories high like the rest, the upper half of which affords four school-rooms, each fifty feet by twenty-four, and two recitation-rooms of half the length. All are furnished with comfortable desks, blackboards, and all the conveniences of a well-ordered school. The lower story, containing the same room, allows for doubling the number of students, which is the captain’s desire.

A walk through these pleasant classrooms is of great interest. Each contains from thirty to forty pupils, under the constant care, for the most part, of one teacher, who, as may be imagined, hasher hands full to keep all busy and quiet, but who does it, somehow, to a remarkable degree. As at Hampton, the great object is to teach English, and then the rudiments of an English education, and the methods employed are similar.

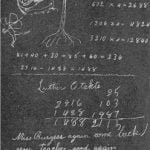

The results possible can not be more fairly shown than by a slate not fairly shown than by a slate not gotten up for the occasion, but filled with the day’s work of one of the pupils–not the best offered, but chosen because it was the work of a little Sioux boy of twelve or thirteen. who, seven months and a half before, had never had any schooling in any language, and did not know a word of English, nor how to make a letter or a figure. He evidently did know how to make pictures, as most of his race do. The blackboards of an Indian recitation-room are usually rich in works of art illustrative of the clay’s doings, or memories of home life.

The industries, agricultural and mechanical, are under, the charge of master-workmen; a skilled farmer, carpenter, wagon-maker, and blacksmith, harness maker, tinner, shoemaker, baker, tailor, and printer. All the boys not learning trades are required to work in turn on the farm. Twelve acres of arable land belong to the post, and twelve more have been rented–two hundred could well be used. The articles manufactured in the shops are taken by government for the agencies. Under this wise encouragement they have already turned out wagons and farm implements, dozens of sets of harness, hundreds of dozens of tinware, and numbers of pairs of shoes, besides doing all the mending, and making all of the girls’ clothing and most of the boys’ underwear.

The amount of students’ work on these varies. No-waste is allowed; the masterwork men do the cutting out and planning for the most part, but the apprentices are brought forward as fast as possible, and the masters say they are up to any apprentices. Indeed, the enthusiastic master-tinsmith put a challenge into a Carlisle paper, which was not taken up, offering to back Roman Nose, one of the St. Augustines, against any apprentice with no longer practice, for $100 a side. One of the Young Sioux shoemakers took his father’s measure when he visited the school, and sent him by mail, after he went home, a pair of boots made entirely by himself.

The two printer apprentices are practiced chiefly upon. the monthly “organ” of the school, the Eadle-Keatah-toh (Morning Star), a very interesting little sheet. One of the bays, however, Samuel Townsend, a Pawnee from Indian Territory, prints a tiny paper, the School News, of which he is both editor and proprietor, writing his own editorials and correcting his owls proof.

The girls’ industrial room makes as good showing as the boys’. Many have learned to sew by hand, and some to run the sewing-machine. Virginia, daughter of the Kiowa chief Stumbling Bear, made a linen shirt, with bosom, entirely by herself, washed and ironed it herself, and sent it to her father. Two Sioux girls have made calico shirts for their fathers. Mending is very neatly done. At Carlisle, as at Hampton, the tender maidens sweeter industry with sentiment, and carefully rummage the darning basket for the stockings of the boys they like the best.

The young St. Augustine from Hampton who went to Indian Territory to collect pupils for Carlisle, took wise advantage of the opportunity to bring back a sweetheart for himself. His naive account of the affair to the captain makes a good companion piece to the Hampton love-letter.

“Long time ago, in my home, Indian Territory, I hunt and I fight. I not think about the girls. Then you take us St. Augustine. By-and-by I learn to talk English. I try to do right. Everybody very good to me. I try do what you say. But I not think about the girls. Then I go Hampton. There many good girls. I study. I learn to work. But I not think about the girls. Then I come Carlisle. I work hard; try to help you. By-and-by you send me Indian Territory for Indian boys and Indian girls. I go get many fifteen. I see all my people, my old friends. But I not think about the girls there. But Laura, she think. She tell me she be my wife. I bring her here, Carlisle. She know English before. She study and sew. Now Laura’s father dead, since come here. Now I think all the time, I think who take care of Laura? I think, by-and-by I find place to work near here; I work very hard. I take care of Laura.”

Besides this frank damsel, who “thinks” to so much purpose, he brought with him a bright little sister of his own, and several brothers and sisters of the other St. Augustines, all of whom are among the most promising of the Carlisle pupils.

Carlisle, like Hampton, has met with much sympathy from its neighbors. It is illustrated, with other points, in an item which appeared in a Carlisle paper during the visit of the Sioux chiefs: “A few mornings since we noticed one of the young Indian men passing in the direction of the post-office, and at his side a comely Indian maiden. The day being warm, the young man carried a huge umbrella to shield them from the sun. Only a short distance in front of them several Indian chiefs were stalking along, wrapped in blankets, and bare-headed. The contrast was so striking that it attracted the attention of many persons on the street. And the conclusion was irresistibly forced upon all who noticed the incident that the Indian school is proving a great success.”

The visit of the Sioux chiefs to Carlisle was prolonged to eight or ten days, and, with the exception of Spotted Tail’s uncomfortable episode, was pleasant and profitable to all.

Accompanying the party was one Indian named Cook, who, not being a chief, had not been invited to come at government expense, so he came at his own expense, all the way from Dakota, to see his little girl at the Carlisle school. He was greatly pleased with her surroundings and progress, and the day after he arrived went out into the town and bought her a white dress, a pair of slippers, and a gold chain and cross. Arrayed in these gifts, he took his precious “Porcelain Face” out with him to have their photographs taken to carry home.

Both Hampton and Carlisle afford excellent opportunity for study of race character. The chief conclusion will be that Indian children are, on the whole, very much like other children, some bright and some stupid, some goad and solve perverse, all exceedingly human. The untamed shyness, so much ill the way of their progress, seems to be as marked in the half-breeds as in those of full blood, unless they have been brought up among white people. It wears off fastest in the younger odes, in constant meeting with strangers, and association with new companions. A certain self-consciousness and sensitive pride is left which is not a bad point in the character. A quick sense of humor is its correlative, perhaps, and both may result from the trained and inherited keenness of observation which appreciates both the fitting and the incongruous.

The pupils at Carlisle and Hampton are in constant receipt of letters from their parents and friends, written some in picture hieroglyphics, some in Sioux, and some, through their interpreters, in English, but all expressive of earnest desire for their progress in school. Abort a hundred of theca letters were sent to the Indian Department by Captain Pratt, forty of which were referred to the Senate in answer to Senator Teller’s resolution against compulsory education for the Cheyenne. Indian sentiments on education expressed by themselves, and the real effect upon Indian parents of sending their children to a white man’s school, no one need question who reads the following specimens of these letters; translated from the Sioux:

“Pine Ridge Agency, Dakota, April 15, 1850.

“My Dear Son,

I send my picture with this. You see that I had my War Jacket on when taken, but I wear white man’s clothes, and am trying to live and act like white men. Be a good boy. We are proud of you, and will be more so when you come back. All our people are building houses and opening up little farms all over the reservation. You may expect to see a big change when you get back. Your mother and all send love.

“Your affectionate father,

“Cloud Shield.”

“Rosebud Agency, January 4, 1880

“My Dear Daughter,

Ever since you left ate I have worked hard, and put up a good house, and am trying to be civilized like the whites, so you will never hear anything bad from me. When Captain Pratt was here he came to my house, and asked me to let yon go to school. I want you to be a good girl and study. I have dropped all the Indian ways, and am getting like a white man, and don’t do anything but what the agent tells me. I listen to him. I have always loved you, and it makes me very happy to know that yon are learning. I get my friend Big Star to write.

If you could read and write, I should be very happy.

Your father,

Brave Bull

“Why do yon ask for moccasins? I sent you there to be like a white girl, and wear shoes.”

A small Indian girl who wanted to exhibit her knowledge of a good big English word, announced that she had come East to be “cilyized.” I hope I have shown sufficiently that it is the effort of Hampton and Carlisle not to sillyize the Indian. Let us not, on the other hand, sillyize ourselves. One great lesson of the missionary work of fifty years has been to work with nature and not against nature; the next must be to be content with natural results. We forget that we our ourselves but the saved remnant of a race. I can not do better on this point for both schools than to quote from an address of General Armstrong: ” The question is most commonly asked, Can Indians be taught? That is not the question. Indian minds are quick; their bodies are greater care than their minds; their character is the chief concern of their teachers. Education should be first for the heart, then for the health, and last for the mind, reversing the custom of putting the mind before physique and character. This is the Hampton idea of education.”