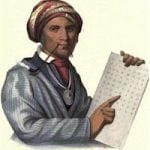

Inventor of the Cherokee Alphabet

The portrait of this remarkable individual is one of great interest. It presents a mild, engaging countenance, entirely destitute of that wild and fierce expression which almost invariably marks the features, or characterizes the expression of the American Indians and their descendants. It exhibits no trace of the ferocity of the savage; it wants alike the vigilant eye of the warrior and the stupid apathy of the less intellectual of that race. The contour of the face, and the whole style of the expression, as well as the dress, are decidedly Asiatic, and might be triumphantly cited in evidence of the oriental origin of our tribes, by those who maintain that plausible theory. It is not merely intelligent and thoughtful, but there are almost a feminine refinement and a luxurious softness about it, which might characterize the features of an eastern sage, accustomed to ease and indolence, but are little indicative of an American origin, or of a mind formed among the wilds of our western frontier.

At an early period in the settlement of our colonies, the Cherokees received with hospitality the white men who went among them as traders; and having learned the value of articles of European fabric, became, in some measure, dependent upon this traffic. Like other Indians they engaged in hostilities against us, when it suited their convenience, or when stimulated by caprice or the love of plunder. But as our settlements approached, and finally surrounded them, they were alike induced by policy, and compelled by their situation, to desist from their predatory mode of life, and became, comparatively, inoffensive neighbors to the whites. The larger number continued to subsist by hunting, while a few engaged in agriculture. Inhabiting a fertile country, in a southern climate, within the limits of Georgia, their local position held out strong temptations to white men to settle among them as traders, and many availed themselves of these advantages. With the present object of carrying on a profitable traffic, and the ulterior view of acquiring titles to large bodies of land, they took up their residence among the Indians, and intermarried with the females of that race. Some of these were prudent, energetic men, who made themselves respected, and acquired influence, which enabled them to rank as head men, and to transmit the authority of chiefs to their descend ants. Many of them became planters, and grew wealthy in horses and cattle, and in negro slaves, which they purchased in the southern states. The only art, however, which they introduced, was that of agriculture; and this but few of the Indians had the industry to learn and practice, further than in the rude cultivation of small fields of corn by the squaws.

In this condition they were found by the missionaries who were sent to establish schools, and to introduce the Gospel. The half-breeds had now become numerous; many of them were persons of influence, using with equal facility the respective tongues of their civilized and savage ancestors, and desirous of procuring for their children the advantages they had but partially enjoyed themselves. By them the missionaries were favorably received, their exertions encouraged, and their schools sustained; but the great mass of the Cherokees were as little improved by these as other portions of the race have been by similar attempts.

Sequoyah, or, as he was commonly called, George Guess, is the son of a white man, named Gist, and of a female who was of the mixed blood. The latter was perfectly untaught and illiterate, having been reared in the wigwam in the laborious and servile habits of the Indian women. She soon became either a widow or a neglected wife, for in the infancy of George, we hear nothing of the father, while the mother is known to have lived alone, managing her little property, and maintaining herself by her own exertions. That she was a woman of some capacity, is evident from the undeviating affection for herself with which she inspired her son, and the influence she exercised over him, for the Indians have naturally but little respect for their female relations, and are early taught to despise the character and the occupations of women. Sequoyah seems to have had no relish for the rude sports of the Indian boys, for when quite young he would often stroll off alone into the woods, and employ himself in building little houses with sticks, evincing thus early an ingenuity which directed itself towards mechanical labors. At length, while yet a small boy, he went to work of his own accord, and built a milk-house for his mother. Her property consisted chiefly in horses and cattle, that roamed in the woods, and of which she owned a considerable number. To these he next turned his attention, and became expert in milking the cows, strain ing the milk, and putting it away with all the care and neatness of an experienced dairyman. He took care of the cattle and horses, and when he grew to a sufficient size, would break the colts to the saddle and harness. Their farm comprised only about eight acres of cleared ground, which he planted in corn, and cultivated with the hoe. His mother was much pleased with the skill and industry of her son, while her neighbors regarded him as a youth of uncommon capacity and steadiness. In addition to her rustic employments, the active mother opened a small traffic with the hunters, and Sequoyah, now a hardy stripling, would accompany these Tough men to the woods, to make selections of skins, and bring them home. While thus engaged he became himself an expert hunter; and thus added, by his own exertions, to the slender income of his mother. When we recollect that men who live on a thinly populated frontier, and especially savages, incline to athletic exercises, to loose habits, and to predatory lives, we recognize in these pursuits of the young Sequoyah, the indications of a pacific disposition, and of a mind elevated above the sphere in which he was placed. Under more favorable circumstances he would have risen to a high rank among intellectual men.

The tribe to which he belonged, being in the habit of wearing silver ornaments, such as bracelets, arm-bands, and broaches, it occurred to the inventive mind of Sequoyah, to endeavor to manufacture them; and without any instruction he commenced the labors of a silversmith, and soon became an expert artisan. In his intercourse with white men he had become aware that they possessed an art, by means of which a name could be impressed upon a hard substance, so as to be comprehended at a glance, by any who were acquainted with this singular invention; and being desirous of identifying his own work, he requested Charles Hicks, afterwards a chief of the Cherokees, to write his name. Hicks, who was a half-blood, and had been taught to write, complied with his desire, but spelled the name George Guess, in conformity with its usual pronunciation, and this has continued to be the mode of writing it. Guess now made a die, containing a facsimile of his name, as written by Hicks, with which he stamped his name upon the articles which he fabricated.

He continued to employ himself in this business for some years, and in the meanwhile turned his attention to the art of drawing. He made sketches of horses, cattle, deer, houses, and other familiar objects, which at first were as rude as those which the Indians draw upon their dressed skins, but which improved so rapidly as to present, at length, very tolerable resemblances of the figures intended to be copied. He had, probably, at this time, never seen a picture or an engraving, but was led to these exercises by the stirrings of an innate propensity for the imitative arts. He became extremely popular. Amiable, accommodating, and unassuming, he displayed an industry uncommon among his people, and a genius which elevated him in their eyes into a prodigy. They flocked to him from the neighborhood, and from distant settlements, to witness his skill, and to give him employment; and the untaught Indian gazed with astonishment at one of his own race who had spontaneously caught the spirit, and was rivaling the ingenuity of the civilized man. The females, especially, were attracted by his manners and his skill, and lavished upon him an admiration which distinguished him as the chief favorite of those who are ever quick-sighted in discovering the excellent qualities of the other . sex.

These attentions were succeeded by their usual consequences. Genius is generally united with ambition, which loves applause, and is open to flattery. Guess was still young, and easily seduced by adulation. His circle of acquaintance became enlarged, the young men courted his friendship, and much of his time was occupied in receiving visits, and discharging the duties of hospitality. On the frontier there is but one mode of evincing friendship or repaying civility drinking is the universal pledge of cordiality, and Guess considered it necessary to regale his visitors with ardent spirits. At first his practice was to place the bottle before his friends, and leave them to enjoy it, under some plea of business or disinclination. An innate dread of intemperance, or a love of industry, preserved him for some time from the seductive example of his reviling companions. But his caution subsided by degrees, and he was at last prevailed upon to join in the bacchanalian orgies provided by the fruits of his own industry. His laborious habits, thus broken in upon, soon became undermined, his liberality increased, and the number of his friends was rapidly enlarged. He would now purchase a keg of whisky at a time, and, retiring with his companions to a secluded place in the woods, become a willing party to those boisterous scenes of mad intoxication which form the sole object and the entire sum of an Indian revel. The common effect of drinking, upon the savage, is to increase his ferocity, and sharpen his brutal appetite for blood; the social and enlivening influence ascribed to the cup by the Anacreontic song, forms no part of his experience. Drunkenness, and not companionship, is the purpose in view, arid his deep potations, imbibed in gloomy silence, stir up the latent passions that he is trained to conceal, but not to subdue. In this respect, as in most others, Sequoyah differed from his race. The inebriating draught, while it stupefied his intellect, warmed and expanded his benevolence, and made him the best natured of sots. Under its influence he gave advice to his comrades, urging them to forgive injuries, to live in peace, and to abstain from giving offense to the whites, or to each other. When his companions grew quarrelsome, he would sing songs to amuse them, and while thus musically employed would often fall asleep. Guess was in a fair way of becoming an idle, a harmless, and a useless vagabond; but there was a redeeming virtue in his mind, which enabled it to react against temptation. His vigorous intellect foresaw the evil tendencies of idleness and dissipation, and becoming weary of a life so uncongenial with his natural disposition, he all at once gave up drinking, and took up -the trade of a blacksmith. Here, as in other cases, he was his own instructor, and his first task was to make for himself a pair of bellows; having effected which, he proceeded to make hoes, axes, and other of the most simple implements of agriculture. Before he went to work, in the year 1820, he paid a visit to some friends residing at a Cherokee village on the Tennessee river, during which a conversation occurred on the subject of the art of writing. The Indians, keen and quick-sighted with regard to all the prominent points of difference between themselves and the whites, had not failed to remark, with great curiosity and surprise, the fact that what was written by one person was understood by another, to whom it was delivered, at any distance of time or place. This mode of communicating thoughts, or of recording facts, has always been the subject of much inquiry among them; the more intelligent have sometimes attempted to deter the imposition, if any existed, by showing the same writing to different persons; but finding the result to be uniform, have become satisfied that the white men possess a faculty unknown to the Indians, and which they suppose to be the effect of sorcery, or some other supernatural cause. In the conversation alluded to, great stress was laid on this power of the white man on his ability to put his thoughts on paper, and send them afar off to speak for him, as if he who wrote them was present. There was a general expression of astonishment at the ingenuity of the whites, or rather at their possession of what most of those engaged in the conversation considered as a distinct faculty, or sense, and the drift of the discussion turned upon the inquiry whether it was a faculty of the mind, a gift of the Great Spirit, or a mere imposture. Guess, who had listened in silence, at length remarked, that he did not regard it as being so very extraordinary. He considered it an art, and not a gift of the Great Spirit, and he believed he could invent a plan by which the red men could do the same thing. He had heard of a man who had made marks on a rock, which other white men interpreted, and he thought he could also make marks which would be intelligible. He then took up a whetstone, and began to scratch figures on it with a pin, remarking, that he could teach the Cherokees to talk on paper like white men. The company laughed heartily, and Guess remained silent during the remainder of the evening. The subject that had been discussed was one upon which he had long and seriously reflected, and he listened with interest to every conversation which elicited new facts, or drew out the opinions of other men. The next morning he again employed himself in making marks upon the whetstone, and repeated, that he was satisfied he could invent characters, by the use of which the Cherokees could learn to read.

Full of this idea, he returned to his own home, at Will’s town, in Will’s valley, on the southern waters of the Coosa river, procured paper, which he made into a book, and commenced making characters. His reflections on the subject had led him to the conclusion, that the letters used in writing represented certain words or ideas, and being uniform, would always convey to the reader the same idea intended by the writer provided the system of characters which had been taught to each was the same. His project, there fore, was to invent characters which should represent words; but after proceeding laboriously for a considerable time, in prosecution of this plan, he found that it would require too many characters, and that it would be difficult to give the requisite variety to so great a number, or to commit them to memory after they should be invented. But his time was not wasted; the dawn of a great discovery was breaking upon his vision; and although he now saw the light but dimly, he was satisfied that it was rapidly increasing. He had imagined the idea of an alphabet, and convinced himself of the practicability of framing one to suit his own language. If it be asked why he did not apply to a white man to be taught the use of the alphabet already in existence, rather than resort to the hope less task of inventing another, we reply, that he probably acted upon the same principle which had induced him to construct, instead of buying, a pair of bellows, and had led him to teach him self the art of the blacksmith, in preference to applying to others for instruction. Had he sought information, it is not certain he could have obtained it, for he was surrounded by Indians as illiterate as himself, and by whites who were but little better informed; and he was possessed, besides, of that self-reliance which renders genius available, and which enabled him to appeal with confidence to the resources of his own mind. He now conceived the plan of making characters to represent sounds, out of which words might be compounded a system in which single letters should stand for syllables. Acting upon this idea, with his usual perseverance, he worked diligently until he had invented eighty-six characters, and then considered that he had completely attained his object.

While thus engaged he was visited by one of his intimate friends, who told him he came to beg him to quit his design, which had made him a laughing-stock to his people, who began to consider him a fool. Sequoyah replied, that he was acting upon his own responsibility, and as that which he had undertaken was a personal matter, which would make fools of none beside himself, he should persevere.

Being confirmed in the belief that his eighty-six characters, with their combinations, embraced the whole Cherokee language, he taught them to his little daughter, Ahyokah, then about six years of age. After this he made a visit to Colonel Lowry, to whom, although his residence was but three miles distant, he had never mentioned the design which had engaged his constant attention for about three years. But this gentleman had learned, from the tell tale voice of rumor, the manner in which his ingenious neighbor was employed, had regretted the supposed misapplication of his time, and participated in the general sentiment of derision with which the whole community regarded the labors of the once popular artisan, but now despised alphabet maker. “Well,” said Colonel Lowry, “I suppose you have been engaged in making marks.” “Yes,” replied Guess; “when a talk is made and put down, it is good to look at it afterwards.” Colonel Lowry suggested, that Guess might have deceived himself, and that, having a good memory, he might recollect what he had intended to write, and suppose he was reading it from the paper. “Not so,” rejoined Guess; “I read it.”

The next day Colonel Lowry rode over to the house of Guess, when the latter requested his little daughter to repeat the alpha bet. The child, without hesitation, recited the characters, giving to each the sound which the inventor had assigned to it, and per forming the task with such ease and rapidity that the astonished visitor, at its conclusion, uttered the common expression ” Yoh!” with which the Cherokees express surprise. Unwilling, however, to yield too ready an assent to that which he had ridiculed, he added, “It sounds like Muscogee, or the Creek language;” meaning to convey the idea that the sounds did not resemble the Cherokee. Still there was something strange in it. He could not permit himself to believe that an illiterate Indian had invented an alphabet, and perhaps was not sufficiently skilled in philology to bestow a very careful investigation upon the subject. But his attention was arrested; he made some further inquiry, and began to doubt whether Sequoyah was the deluded schemer which others thought him.

The truth was, that the most complete success had attended this extraordinary attempt, and George Guess was the Cadmus of his race. Without advice, assistance, or encouragement ignorant alike of books and of the various arts by which knowledge is disseminated with no prompter but his own genius, and no guide but the light of reason, he had formed an alphabet for a rude dialect, which, until then, had been an unwritten tongue ! It is only necessary to state, in general, that, subsequently, the invention of Guess was adopted by intelligent individuals engaged in the benevolent attempt to civilize the Cherokees, and it was determined to prepare types for the purpose of printing books in that tongue. Experience demonstrated that Guess had proved himself successful, and he is now justly esteemed the Cadmus of his race. The conception and execution are wholly his own. Some of the characters are in form like ours of the English alphabet; they were copied from an old spelling-book that fell in his way, but have none of the powers or sounds of the letters thus copied. The following are the characters systematically arranged with the sounds.

Alphabet omitted because I do not have a Cherokee font.

Sounds represented by vowels:

| a as a | in father, or short as a in rival |

| e as a | in hate, or short as e in met |

| i as i | in pique, or short as i in pit, |

| o as aw | in law, or short as o in not |

| u as oo | in fool, or short as u in pull |

| v as u | in but, nasalized. |

Consonant Sounds:

| g nearly as in English, but approaching to k. d nearly as in English, but approaching to t. h, k, l, m, n, q, s, t, w, y, as in English.Syllables beginning with g except s, have sometimes the power of k; A, S, O, are sometimes sounded to, tu, tv; and syllables written with the t1, except £, sometimes vary to d1. (I know the symbols are wrong, if you can provide the proper ones, please let me know) |

Guess completed his work in 1821. Several of his maternal uncles were at that time distinguished men among the Cherokees. Among them was Keahatahee, who presided over the beloved town, Echota, the town of refuge, and who was one of two chiefs who were killed by a party of fourteen people, while under the protection of a white flag, at that celebrated place. One of these persons observed to him, soon after he had made his discovery, that he had been taught by the Great Spirit. Guess replied, that he had taught himself. He had the good sense not to arrogate to himself any extraordinary merit, in a discovery which he considered as the result of an application of plain principles. Having accomplished the great design, he began to instruct others, and after teaching many to read and write, and establishing his reputation, he left the Cherokee nation in 1822, and went on a visit to Arkansas, where he taught those of his tribe who had emigrated to that country. Shortly after, and before his return home, a correspondence was opened between the Cherokees of the west and those of the east of the Mississippi, in the Cherokee language. In 1823, he determined to emigrate to the west of the Mississippi. In the autumn of the same year, the general council of the Cherokee nation passed a resolution, awarding to Guess a silver medal, in token of their regard for his genius, and of their gratitude for the eminent service he rendered to his people. The medal, which was made at Washington city, bore on one side two pipes, on the other a head, with this inscription “Presented to George Gist, by the General Council of the Cherokee nation, for his ingenuity in the invention of the Cherokee Alphabet.” The inscription was the same on both sides, except that on one it was in English, and on the other in Cherokee, and in the characters invented by Guess. It was intended that this medal should be presented at a council, but two of the chiefs dying, John Ross, who was now the principal chief, being desirous of the honor and gratification of making the presentation, and not knowing when Guess might return to the nation, sent it to him with a written address.

Guess has never since revisited that portion of his nation which remains upon their ancient hunting-grounds, east of the Mississippi. In 1828, he was deputed as one of a delegation from the western Cherokees, to visit the President of the United States, at Washing ton, when the likeness which we have copied was taken.

The name which this individual derived from his father was, as we have seen, George Gist; his Indian name, given him by his mother, or her tribe, is Sequoyah; but we have chosen to use chiefly in this article, that by which he is popularly known George Guess.