The reader of Oregon history will remember that mention is made of the massacre of the Ward train by the Snake Indians near Fort Boise in the autumn of 1854. Major Granville O. Haller, stationed at Fort Dalles, made a hasty expedition into the Snake country, intended to show the Indians that the government would not remain inactive while its citizens were subjected to these outrages. The march served no other purpose than to give this notice, for the guilty Indians had retired into their mountain fastnesses, and the season being late for re-crossing the Blue Mountains, Haller returned to The Dalles. The following summer, however, he led another expedition into the Boise Valley, and following up the trails, finally captured and executed the murderers.

Hardly had he returned to Fort Dalles when news reached him of trouble in the Yakima country. In the spring of 1855 gold had been discovered in the region of Fort Colville, which caused the usual rush of miners to the gold fields, making it difficult for Governor Stevens to restrain his escort from deserting. 1

He proceeded on his mission, informing the tribes of the Upper Columbia, Kettle Falls, Spokanes, Pend d’Oreilles, and Coeur d’Alenes, that on his return he would negotiate with them for the sale of their lands.

But the Indians were not satisfied with their treaty, nor with the influx of white men. About the first of August Pierre Jerome, chief of the Kettle Falls people, declared that no Americans should pays through his country. From Puget Sound several small parties set forth for Colville by the Nisqually pass and the trail leading through the Yakima country by the way of the catholic mission of Ahtanahm, and about the middle of September it was rumored that some of them had been killed by the Yakimas. A. J. Bolon, special agent for the Yakimas, was on his way to the Spokane country, where he expected to meet Stevens on his return from Fort Benton, and assist in the appointed councils and treaties with this and the neighboring tribes. He had passed The Dalles on this errand when he was met by Chief Garry of the Spokanes with these reports, and he at once turned back to investigate them.

The Catholic Mission, near which was the home of Kamiakin, was between sixty and seventy miles in a north-easterly direction from The Dalles, and to this place he determined to go in order to learn from Kamiakin himself the truth or falsity of the stories concerning the Yakimas. 2 Unattended he set out on this business, to show by his coming alone his confidence in the good faith of the tribe, and to disarm any fears they might have of the intentions of the white people. 3 His absence being protracted beyond the time required, Nathan Olney, agent at The Dalles, sent out an Indian spy, who returned with the information that Bolon had been murdered while returning to The Dalles, by the order of Kamiakin, and by the hand of his nephew, a son of Owhi, his half-brother, and a chief of the Umatillas, who shot him in the back while pretending to escort him on his homeward journey, cut his throat, killed his horse, and burned both bodies, together with whatever property was attached to either.

All this Kamiakin confessed to the Des Chutes chief, who acted as spy, saying that he was determined on war, which he was prepared to carry on, if necessary, for five years; 4 that no Americans should come into his country; that all the tribes were invited to join him, and that all who refused would be held to be foes, who would be treated in the same manner as Americans-the adults killed, and the children enslaved. The report of the spy was confirmed by a letter from Brouillette, who wrote to Olney that war had been the chief topic among the Yakimas since their return from the council. 5 It was now quite certain that an Indian war, more or less general, was at hand.

Without any authoritative promulgation, the rumor of the threatened coalition spread, and about the 20th of September returning miners brought the report that certain citizens had been killed in passing through the Yakima country. As soon as it became certainly known, 6 Acting Governor Mason made a requisition upon forts Vancouver and Steilacoom for troops to protect travelers by that route, and also intimated to the commanding officers that, as Governor Stevens expected to be in the Spokane country in September, under the circumstances a detachment of soldiers might be of assistance to him.

Meanwhile Major Raines, who regarded Kamiakin and Peupeumoxmox as the chiefs most to be dreaded, ordered eighty-four men under Haller from Fort Dalles to pass into the Yakima country and cooperate with a force sent from Steilacoom. Haller set forth on the 3d of October. His route lay over a gradual elevation for ten miles north of the Columbia to the summit of the bald range of hills constituting the Klikitat Mountains. Beyond these was the Klikitat Valley, fifteen miles in width, north of which stretched the timbered range of the Simcoe Mountains, beyond which again was the Simcoe Valley, on the northern boundary of which, about sixty miles from The Dalles, was the home of Kamiakin and the Ahtanahm mission, the objective point of the expedition.

It was not until the third day, and when the troops were descending a long hill to a stream skirted with dense thickets of small trees, that any Indians were seen. At this point, about three o’clock in the afternoon, the Indians attacked, 7 being concealed in the thick undergrowth mentioned. There was a sharp engagement lasting until nightfall, when the Yakimas withdrew, leaving Haller with eight killed and wounded men. That night the troops lay upon their arms. In the morning the attack was renewed, the Indians endeavoring to surround Haller as he moved to a bold eminence at the distance of a mile. Here the troops fought all day without water and with little food. It was not until after dark that a messenger was dispatched to The Dalles to apprise Raines of the situation of the command and obtain reinforcements.

The cavalry horses and pack-animals, being by this time in a suffering state, were allowed to go free at night to find water and grass, except those necessary to transport the wounded and the ammunition. Toward evening of the third day the troops moved down to the river for water, and not meeting with any resistance, Haller determined to fall back toward The Dalles with his wounded. The howitzer was spiked and buried, and such of the baggage and provisions as could not be transported was burned. The command was organized in two divisions, the advance under Haller to take care of the wounded, and the rear under Captain Russell to act as guard. In the darkness the guide led the advance off the trail, on discovering which Haller ordered fires to be lighted in some fir trees to signal to the rear his position, at the same time revealing it to the Indians, who, as soon as daylight came, swarmed around him on every side, following and harassing the command for ten miles. On getting into the open country a stand was made, and Haller’s division fought during the remainder of the day, resuming the march at night, Russell failing to discover his whereabouts. When twenty-five miles from The Dalles Haller was met by Lieutenant Day of the 3d artillery with forty-five men, who, finding the troops in retreat, proceeded to the border of the Yakima country merely to keep up a show of activity on the part of the army. Lieutenant W. A. Slaughter with fifty men had crossed the Cascades by the Nachess pass, with the design of reinforcing Haller, but finding a large number of Indians in the field, and hearing that Haller was defeated, prudently fell back to the west side of the mountains.

Such were the main incidents of Haller’s Yakima campaign, in which five men were killed, seventeen wounded, and a large amount of government property destroyed, abandoned, and captured. 8 The number of Indians killed was unknown, but thought to be about forty.

Preparations for war were now made in earnest, both by the military and the citizens, though not without the usual attendant bickering: A proclamation was issued, calling for one company to be enrolled in Clarke County, at Vancouver, and one in Thurston County, at Olympia, to consist of eighty- seven men, rank and file, with orders to report to the commanding officers of Steilacoom and Vancouver, and as far as possible to provide their own arms and equipments. The estimated number of hostile Indians in the field was 1,500. Application for arms was made by Mason through Tilton, the lately arrived surveyor-general, to Sterrett and Pease, commanders respectively of the sloop of war Decatur and the revenue-cutter Jefferson Davis, then in the Sound, and the request granted.

There was organized at Olympia the Puget Sound Mounted Volunteers, Company B, with Gilmore Hays as captain, James S. Hurd 1st Lieutenant, William Martin 2d Lieutenant, Joseph Gibson, Henry D. Cock, Thomas Prather, and Joseph White sergeants; Joseph S. Taylor, Whitfield Kirtley, T. Wheelock, and John Scott corporals-who reported themselves to Captain Maloney, in command of Fort Steilacoom, on the 20th, and on the 21st marched under his command for White River to reinforce Slaughter, quartermaster at Steilacoom, who had gone through the Nachess pass into the hostile country with forty men, and had fallen back to the upper prairies, but who awaited the organization of an army of invasion to return to the Yakima country.

After due proclamation, Mason issued a commission to Charles H. Eaton to organize a company of rangers, to consist of thirty privates and a complement of officers. 9 The company was immediately raised, and took the field on the 23d to act as a guard upon the settlements, and to watch the passes through the mountains. On the 22d a proclamation was issued calling for four companies, to be enrolled at Vancouver, Cathlamet, Olympia, and Seattle, and to hold themselves, after organizing and electing their officers, in reserve for any emergency which might arise. James Tilton was appointed adjutant-general of the volunteer forces of the territory, and Major Raines, who was about to take the field against the Yakimas, brigadier-general of the same during the continuance of the war. Company A of the Mounted Volunteers organized in Clarke county was commanded by William Strong, and though numbering first, was not fully organized until after Company B had been accepted and mustered into the service of the United States. Special Indian agent B. F. Shaw, who took the place of Bolon, was instructed by Mason to raise a company and go and meet and escort back Governor Stevens. Several companies were raised in Oregon, as I have elsewhere related, J. W. Nesmith being placed in command, with orders to proceed to the seat of war and cooperate with Raines.

On the 30th of October Raines marched for the Yakima Country, having been reinforced by 128 regulars and 112 volunteers from Washington, including Strong’s company of 63 and Robert Newell’s company of 35 men, making a force of about 700. On the 4th of November Nesmith, with four companies of Oregon volunteers, overtook Raines’ command, proceeding with it to the Simcoe Valley, where they arrived on the 7th. Little happened worth relating. There was a skirmish on the 8th, in which the Oregon volunteers joined with the regulars in fighting the Indians, who, now that equal numbers were opposed to them, were less bold. When it came to pursuit, they had fresh horses and could always escape. 10 They were followed and driven up the Yakima, to a gap through which flows that stream, and where the heights had been well fortified, upon which they took their stand; but on being charged upon by the regulars, under Haller and Captain Augur, fled down the opposite side of the mountain, leaving it in possession of the troops, 11 who returned to camp. The Indians showing themselves again on the 10th, Major Armstrong of the volunteers, with the company of Captain Hayden and part of another under Lieutenant Hanna, passed through the defile and attempted to surround them and cut off their retreat; but owing to a misunderstanding, the charge was made at the wrong point, and the Indians escaped through the gap, scattering among the rocks and trees. On the 10th all the forces now in the Yakima country moved on toward the Ahtanahm mission, skirmishing by the way and capturing some of the enemy’s horses, but finding the country about the mission and the mission itself quite deserted. After a few more unimportant movements Nesmith proceeded to Walla Walla, to hold that valley against hostile tribes, while Raines, leaving his force to build a block-house on the southern border of the Yakima country, reported in person to General Wool, who had just arrived at Vancouver with a number of officers, fifty dragoons, 4,000 stand of arms, and a large amount of ammunition. Wool ordered the troops in Oregon to be massed at The Dalles to await his plan of operations, which, so far as divulged, was to establish a post at the Walla Walla to keep in check the other tribes while prosecuting war against the Yakimas. An inspection of the troops and horses, however, revealed the fact that many of the soldiers were without sufficient clothing, and that few of their animals were fit for service. The quartermaster was then directed to procure means of transportation from the people of the Willamette, but owing to the heavy drain made upon them in furnishing the volunteer force, wagons and horses were not to be had, and they were ordered from Benicia, California, and boats and forage from San Francisco. Before these could arrive the Columbia was frozen over, and communication with the upper country completely severed; but not before Major Fitzgerald with fifty dragoons from Fort Lane had arrived at The Dalles, 12 and Keyes’ artillery company had been sent to Fort Steilacoom to remain in garrison until the return of milder weather.

The ice remained in the lower Columbia but three weeks, and on the 11th of January 1856, the mail steamer brought despatches informing Wool of Indian disturbances in California and southern Oregon, which demanded his immediate return to San Francisco. While passing down the river he met Colonel George Wright, with eight companies of the 9th infantry regiment, to whom he assigned the command of the Columbia River district; and at sea he also met Lieutenant Colonel Silas Casey, with two companies of the same regiment, whom he assigned to the command of the Puget Sound district.

Colonel Wright was directed to establish his headquarters at The Dalles, where all the troops intended to operate in the upper country would be concentrated; and as soon as the ice was out of the river, and the season would permit, to establish a post in the neighborhood of Fort Walla Walla, and another at the fishery on the Yakima River, near the crossing of the road from Walla Walla to Fort Steilacoom; and also an intermediate post between the latter and Fort Dalles, the object of the latter two posts being to prevent the Indians taking fish in the Yakima or any of its tributaries, or the tributaries of the Columbia. The occupation of the country between the Walla Walla and Snake rivers, and on the south side of the Columbia, it was believed, would soon bring the savages to terms.

During this visit, as indeed on some other occasions both before and after, Wool did not deport himself as became a man occupying an important position. He censured everybody, not omitting Raines and Haller, but was particularly severe upon territorial officers and volunteers. He ordered disbanded the company raised by order of Mason to go to the relief of Governor Stevens returning from the Blackfoot country 13 although Raines put forth every argument to induce him to send it forward. This conduct of Wool was bitterly resented by Stevens, who quoted the expressions used by Wool in his report to the departments at Washington, and in a letter to the general himself. 14 The effect of Wool’s course was to raise an impassable barrier between the regular and volunteer officers, and to leave the conduct of the war practically in the hands of the latter.

Meanwhile affairs on the Sound were not altogether quiet. From the rendezvous at Nathan Eaton’s house, on the 24th of October, 1855, went nineteen rangers under Captain Charles Eaton to find Leschi, a Yakima-Nisqually chief; who was reported disaffected; but the chief was not at home. Encamping at the house of Charles Baden, Eaton divided his company and examined the country, sending Quartermaster Miller 15 to Fort Steilacoom for supplies. While reconnoitering, Lieutenant McAllister and M. Connell, 16 of Connell’s prairie, were killed, and the party took refuge in a log-house, where they defended themselves till succor came.

Elsewhere a more decisive blow was struck. As early as the 1st of October Porter had been driven from his claim at the head of White River Valley, and soon afterward all the farmers left their claims and fled to Seattle with their families, where a block-house was erected. Soon after the sloop of war Decatur anchored in front of Seattle, the commander offering his services to assist and defend the people in case of an occasion arriving; Acting-governor Mason, who had made a tour of White ”Valley without meeting any signs of a hostile demonstration, endeavoring to reassure the settlers, they thereupon returning to gather their crops, of which they stood much in need.

The Indians, who were cognizant of all these movements, preserved a deceitful quiet until Maloney and Hays had left the valley for the Yakima country, believing that they were doomed to destruction, while the inhabitants left behind were to become an easy prey. On the morning of the 28th, Sunday, they fell upon the farming settlements, killing three families of the immigration of 1854, H. H. Jones and wife, George E. King and wife, W. H. Brannan, wife and child, Simon Cooper, and a man whose name was unknown. An attack was made upon Cox’s place, and Joseph Lake wounded, but not seriously. Cox, with his wife and Lake, fled and escaped, alarming the family of Moses Kirkland, who also escaped, these being all the settlers who had returned to their homes. The attack occurred at eight o’clock in the morning, and about the same hour in the evening the fugitives arrived at Seattle, twenty-five miles distant. On the following morning a friendly Indian brought to the same place three children of Mr Jones, who had been spared, and on the same day C. C. Hewitt, with a company of volunteers, started for the scene of the massacre to bury the dead, and if possible, rescue some living.

That the settlers of the Puyallup below the crossing did not share the fate of those on White River was owing to the warning of Kitsap the elder, 17 who, giving the alarm, enabled them to escape in the night, even while their enemies prowled about waiting for the dawn to begin their work of slaughter. From the Nachess River Captain Maloney sent despatches to Governor Mason by volunteers William Tidd and John Bradley, who were accompanied by A. B. Moses, M. P. Burns, George Bright, Joseph Miles, and A. B. Rabbeson. They were attacked at several points on the route, Moses 18 and Miles 19 losing their lives, and the others suffering great hardships.

In the interim, Captain Maloney, still in ignorance of these events, set out with his command to return to Steilacoom, whence, if desired, he could proceed by the way of The Dalles to the Yakima Valley. On reaching Connell’s prairie, November 2d, he found the house in ashes, and discovered, a mile away from it, the body of Lieutenant McAllister. On the morning of the 3d fifty regulars under Slaughter, with fifty volunteers under Hays, having ascertained the whereabouts of the main body, pursued them to the crossing of White River, where, being concealed, they had the first fire, killing a soldier at the start. The troops were unable to cross, but kept up a steady firing across the river for six hours, during which thirty or more Indians were killed and a number wounded. One soldier was slightly wounded, besides which no loss was sustained by the troops, regular or volunteer.

Maloney remained at Camp Connell, keeping the troops moving, for some days. On the 6th Slaughter with fifty of Hays’ volunteers was attacked at the crossing of the Puyallup, and had three men mortally wounded, 20 and three less severely.

The officer left in command of Fort Steilacoom when Maloney took the field was Lieutenant John Nugen. Upon receiving intelligence of the massacre on White River, he made a call upon the citizens of Pierce county to raise a company of forty volunteers, who immediately responded, a company under Captain W. H. Wallace reporting for service the last of October.

By the middle of November the whole country between Olympia and the Cowlitz was deserted, the inhabitants, except the volunteers, comprising half the able-bodied men in the territory, having shut themselves up in block-houses, and taken refuge in the towns defended by home-guards. 21

Special Indian agent Simmons published a notice on the 12th of November, that all the friendly Indian: within the limits of Puget Sound district should rendezvous at the head of North Bay, Steilacoom, Gig Harbor, Nisqually, Vashon Island, Seattle, Port Orchard, Penn Cove, and Oak Harbor; J. B. Webber being appointed to look after all the encampments above Vashon Island; D. S. Maynard to look after those at Seattle and Port Orchard; R. C. Fay and N. D. Hill to take in charge those on Whidbey Island, as special agents. H. H. Tobin and E. C. Fitzhugh were also appointed special agents. The white inhabitants were notified that it might become necessary to concentrate the several bands at a few points, and were requested to report any suspicious movements on the part of the Indians to the agents. By this means it was hoped to separate the friendly from the hostile Indians to a great extent, and to weaken the influence of the latter. At this critical juncture, also, Governor Douglas, of Vancouver Island, sent to Nisqually the Hudson’s Bay Company’s steamer Otter, an armed vessel, to remain for a time, and by her also fifty stand of arms and a large supply of ammunition to General Tilton, in compliance with a request forwarded by Acting-governor Mason, November 1st.

The volunteer forces called out or accepted having all reported for service, Captain Maloney arranged a campaign which was to force the friendly Indians upon their reserves, and to make known the lurking-places of their hostile brethren. Lieutenant Slaughter was directed to proceed with his company to White and Green rivers; Captain Hewitt, who was at Seattle with his volunteers, was ordered to march up White and Green rivers and place himself in communication with Slaughter; while Captain Wallace occupied the Puyallup Valley within communicable distance, and Captain Hays took up a position on the Nisqually River, at Muck prairie, and awaited further orders. Lieutenant Harrison, of the revenue-cutter Jefferson Davis, accompanied the expedition as first Lieutenant to Slaughter’s command. Upon the march, which began on the 24th of November, Slaughter was attacked at night at Bidding’s prairie, one mile from the Puyallup, and sustained a loss of forty horses during a heavy fog, which concealed the movements of the Indians. On the morning of the 26th E. G. Price of Wallace’s company, while attending to camp duty, was shot and killed by a lurking foe. The chiefs who commanded in the attack on the night of the 25th were Kitsap and Kanascut of the Klikitats, Quiemuth and Klowowit of the Nisquallies, and Nelson of the Green River and Niscope Indians. During two nights that the troops were encamped on this prairie the Indians continually harassed them by their yells, and by crawling up out of the woods which surrounded the little plain, and under cover of the fog coming close enough to fire into camp in spite of the sentries, who discharged their pieces into the surrounding gloom without effect. Being reinforced on the 26th with twenty-five men of the 4th artillery, just arrived at Fort Steilacoom, Slaughter divided his force, Wallace’s company encamping at Morrison’s place, on the Stuck, where they remained making sorties in the neighborhood, while the main command were occupied in other parts of the valley, no engagement taking place, as the Indians kept out of way in the day-time, which the heavy forest of the Puyallup bottoms rendered it easy to do.

Thus passed another week of extremely disagreeable service, the weather being both cold and rainy. On the 3d of December Lieutenant Slaughter, with sixty men of his own command and five of Wallace’s, left Morrison’s for White River, to communicate with Captain Hewitt, and encamped at the forks of White and Green rivers, on Brannan’s prairie, taking possession of a small log house left standing, and sending word to Hewitt, who was encamped two or three miles below, to meet him there. While a conference was being held, about seven o’clock in the evening of the 4th, the troops permitting themselves a fire beside the door to dry their sodden clothing, the Indians, guided by the light, sent a bullet straight to the heart of Slaughter, sitting inside the doorway, who died without uttering a word. They then kept up a continuous firing for three hours, killing two non-commissioned officers, and wounding six others, one mortally. 22 Nothing that had occurred during the war cast a greater gloom over the community than the death of the gallant Slaughter.

Captain E. D. Keyes, whom Wool had left in command at Port Steilacoom, now notified Mason that it was found necessary to withdraw the troops from the field, as the pack-horses were worn down, and many of the men sick. This announcement put an end for the time to active operations against the Indians, and the troops went into garrison at such points as promised to afford the best protection to the settlers, while the volunteers remained at places where they might assist, waiting for the next turn in affairs.

The snow being now deep in the mountain passes, communication with the Indians east of the Cascades was believed to be cut off; and as the Indians west of the mountains had ceased to attack, there seemed nothing to do but to wait patiently until spring, when General Wool had promised to put troops enough into the field to bring the war to a speedy termination. Thus matters moved along until the companies mustered into the service of the United States on the Sound were disbanded, their three months’ time having expired.

For several weeks the citizens of Seattle had been uneasy, from the belief that the friendly Indians gathered near that place were being tampered with by Leschi. About the 1st of January, 1856, it was discovered that he was actually present at the reserve, making boasts of capturing the agent; and as the authorities very much desired to secure his arrest, Keyes secured the loan of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s steamer Beaver, and sent Maloney and his company to seize and bring him to Fort Steilacoom. But as the Beaver approached the shore to effect a landing, Leschi drew up his forces in battle array to meet the troops, who could only land in squads of three or four from a small boat. Finding that it would not be safe to expose his men in such a manner, and having no cannon to disperse the Indians, Maloney was compelled to return to Steilacoom without accomplishing the object of the expedition.

Keyes then determined to make another effort for the capture of Leschi, and embarking for Seattle in the surveying steamer Active, James Alden commanding, endeavored to borrow the howitzer and launch of the Decatur, which was refused by the new commander, Gansevoort, upon the ground that they were essential to the protection of the town, and must not go out of the bay. Keyes then returned up the Sound to procure a howitzer from the fort, when Leschi, divining that his capture had been determined upon, withdrew himself to the shades of the Puyallup, where shells could not reach him.

Captain Gansevoort took command of the Decatur on the 10th of December, 1855, three days after she had received an injury by striking on a reef, then unknown, near Bainbridge Island, and it became necessary to remove her battery on shore while repairing her keel, a labor which occupied nearly three weeks, or until January 19th, when her guns were replaced. Very soon after a young Dwamish, called Jim, notified Gansevoort that Indians from the east side of the mountains, under Owhi, had united with those on the west side under Coquilton, with the design of dividing their threes into two columns, and making a simultaneous attack on Steilacoom and Seattle, after destroying which they expected to make easy work of the other settlements.

The plan might have succeeded as first conceived, Hewitt’s company being disbanded about this time, and the Decatur being drawn up on the beach; but some Indian scout having carried information of the condition of the man-of-war to the chiefs, it was decided that the capture of the ship, which was supposed to be full of powder, would be the quickest means of destroying the white race, and into this scheme the so-called friendly Indians had entered with readiness.

Gansevoort, feeling confident that he could rely upon Jim’s statement, prepared to meet the impending blow. The whole force of the Decatur was less than 150 men and officers. Of these a small company was left on board the ship, while 96 men, eighteen mariners, and five officers did guard duty on shore.

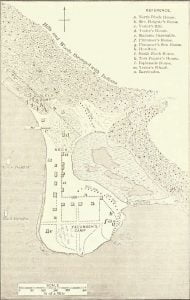

Seattle at this time occupied a small peninsula formed by the bay in front, and a wide and deep swamp at the foot of the heavily wooded hills behind. The connection of the peninsula with the country back was by a narrow neck of land at the north end of the town, and the Indian trail to lakes Washington and Union came in almost directly opposite Yesler’s mill and wharf, where a low piece of ground had been filled in with sawdust. The only other avenue from the back country was by a narrow sand-spit on the south side of the Marsh, which was separated from the town only by a. small stream. Thus the longer line of defense was actually afforded by the swamp, and the points requiring a guard were those in front of the sand-spit and the lake trail; and it was thus that Gansevoort disposed of his force, three divisions being placed to guard the southern entrance, which was most exposed, and one directly across the northern trail.

For two nights guard had been maintained, when on the 24th the Active reappeared at Seattle, having on board Captain Keyes, Special Agent Simmons, and Governor Stevens, just arrived from east of the mountains after his escape from the hostile combination in that country. It does not appear in the narratives whether or not they had a howitzer on board. Leschi, at all events, had already left the reservation. Next day the Active proceeded down the Sound to visit the other reservations, and learn the condition and temper of the Indians under the care of agents, and Captain Gansevoort continued his system of guard-posting.

On the beach above Yesler’s mill, and not far from where the third division, under Lieutenant Phelps, was stationed, was the camp of a chief of the Dwamish tribe, known to the white settlers as Curley, though his proper name was Suequardle, who professed the utmost friendship for his civilized neighbors, and was usually regarded as honest in his professions, the officers of the Decatur reposing much confidence in him. On the afternoon of the 25th another chief from the lake district east of Seattle, called Tecumseh, came into town with all his people, claiming protection against the hostile Indians, who, he said, threatened him with destruction should he not join them in the war upon the settlers. He was kindly received, and assigned an encampment at the south end of town, not far from where the first, second, and fourth divisions were stationed, under Lieutenants Drake, Hughes, and Morris, respectively.

At five o’clock in the afternoon the Decatur crew repaired to their stations, and about eight o’clock Phelps observed, sauntering past, two unknown Indians, of whom he demanded their names and purpose, to which they carelessly answered that they were Lake Indians, and had been visiting at Curley’s encampment. They were ordered to keep within their own lines after dark, and dismissed. But Phelps, not being satisfied with their appearance, had his suspicions still further aroused by the sound of owl-hooting in three different directions, which had the regularity of signals, and which he decided to be such. This impression he reported to headquarters at Yesler’s house, and Curley was dispatched to reconnoiter. At ten o’clock he brought the assurance that there were no Indians in the neighborhood, and no attack need be apprehended during that night.

Two hours after this report was given, a conference was held at Curley’s lodge, between Leschi, Owhi, Tecumseh, and Yark-Keman, or Jim, in which the plan was arranged for an immediate attack on the town, the ‘friendly’ Indians to prevent the escape of the people to the ships in the bay, 23 while the warriors, assembled to the number of more than a thousand in the woods which covered the hills back of town, made the assault. By this method they expected to be able to destroy every creature on shore between two o’clock and daybreak, after which they could attack the vessels.

Fortunately for the inhabitants of Seattle and the Decatur’s crew, Jim was present at this council as a spy, and not as a conspirator. He saw that he needed time to put Gansevoort on his guard, and while pretending to assent to the general plan, convinced the other chiefs that a better time for attack would be when the Decatur’s men, instead of being on guard, had retired to rest after a night’s watch. Their plans being at length definitely settled, Jim found an opportunity to convey a warning to the officers of the Decatur. The time fixed upon for the attack was ten o’clock, when the families, who slept at the blockhouse, had returned to their own houses and were defenseless, “with the gun standing behind the door, 24 as the conspirators, who had studied the habits of the pioneers, said to each other.

During the hours between the conference at Curley’s lodge and daylight, the Indians had crept up to the very borders of the town, and grouped their advance in squads concealed near each house. At 7 o’clock the Decatur’s men returned to the ship to breakfast and rest. At the same time it was observed by Phelps that the non-combatants of Curley’s camp were hurrying into canoes, taking with them their property. On being interrogated as to the cause of their flight, the mother of Jim, apparently in a great fright, answered in a shrill scream, “Hiu Klikitat copa, Tom Pepper’s house! hi-hi-hiu Klikitat!” that is to say, “There arc hosts of Klikitats at Tom Pepper’s house,” which was situated just at the foot of the hills where the sand-spit joined the mainland, and which was within range of Morris’ howitzer.

Instead of being allowed to breakfast, the men were immediately sent ashore again, and given leave to get what rest they could in the loft of Yesler’s mess-house, where refreshments were sent to them, while Captain Gansevoort ordered a shell dropped into Tom Pepper’s house, to make the Indians show themselves if there. The effect was all that could have been anticipated. The boom of the gun had not died away when the blood-curdling war-whoop burst from a thousand stentorian throats, accompanied by a crash of musketry from the entire Indian line. Instantly the four divisions dashed to their stations, and the battle was begun by Phelps’ division charging up the hill east of Yesler’s mill, while those at the south end of town were carrying on a long-range duel across the creek or slough in that quarter. Those of the citizens who were prepared. also took part in the defense of the place. Astonished by the readiness of the white men and the energy of the charge, the Indians were driven to the brow of the hill, and the men had time to retreat to their station before the enemy recovered from their surprise.

Had not the howitzer been fired just when it was, in another moment the attack would have been made without warning, and all the families nearest the approaches butchered before their defenders could have reached them; but the gun provoking the savage war cry betrayed their close proximity to the homes of the citizens, who, terrified by the sudden and frightful clamor, fled wildly to the block-house, whence they could see the flames of burning buildings on the outskirts. A lad named Milton Holgate, brother of the first settler of King county, was shot while standing at the door of the block-house early in the action, and Christian White at a later hour in another part of the town. Above the other noises of the battle could be heard the cries of the Indian women, urging on the warriors to greater efforts; but although they continued to yell and to fire with great persistency, the range was too long from the points to which the Decatur’s guns soon drove them to permit of their doing any execution; or if a few came near enough to hit one of the Decatur’s men, they were much more likely to be hit by the white marksmen.

About noon there was a lull, while the Indians rested and feasted on the beef of the settlers. During this interval the women and children were taken on board the vessels in the harbor, after which an attempt was made to gather from the suddenly deserted dwellings the most valuable of the property contained in them before the Indians should have the opportunity, under the cover of night, of robbing and burning them. This attempt was resisted by the Indians, the board houses being pierced by numerous bullets while visited for this purpose; and the attack upon the town was renewed, with an attempt on the part of Coquilton to bear clown upon the third division in such numbers as to annihilate it, and having done this, to get in the rear of the others. At a preconcerted signal the charge was made, the savages plunging through the bushes until within a few paces before they fired, the volley delivered by them cluing no harm, while the little company of fourteen marines net them so steadily that they turned to shelter themselves behind logs and trees, in their characteristic mode of fighting. Had they not flinched from the muzzles of those fourteen guns-had they thrown themselves on those few men with ardor, they would have blotted them out of existence in five minutes by sheer weight of numbers. But such was not to be, and Seattle was saved by the recoil.

As if to make up for having lost their opportunity, the Indians showered bullets upon or over the heads of the man-of-war’s men, to whose assistance during the afternoon came four young men from Meigs’ mill, the ship’s surgeon, Taylor, and two others, adding a third to this command, besides which a twelve-pounder field-gun was brought into position on the ground, a discharge from which dislodged the most troublesome of the enemy in that quarter.

In the midst of the afternoon’s work, Curley, who had been disappointed so far of his opportunity to make himself a place in history, and becoming excited by the din of battle, suddenly appeared upon the scene, arrayed in fighting costume, painted, armed with a musket and a bow in either hand, which he held extended, and yelling like a demon, pranced oddly about on the sawdust, more ludicrous than fear-inspiring, until, having exhausted some of his bravado, he as suddenly disappeared, thus giving testimony that his friendship for the white race was no greater than his courage.

This defiance of his quondam friends came from anticipating an occasion to distinguish himself at a later hour of the day. Toward evening the assailing Indians were discovered placing bundles of inflammable materials under and about the deserted houses, preparatory to a grand conflagration in the evening, by the light of which the Indians on the reservation and those in the two camps on the beach at Seattle were to assist in attacking and destroying the blockhouse with its inmates. This information, being gathered by scouts, was brought to Gansevoort in time, who resorted to shelling the town as a means of dispersing the incendiaries, which proved successful, and by ten o’clock at night firing had ceased on both sides.

Shells had much more influence with the savages than cannon-balls; for they could understand how so large a ball might fell a tree in their midst, but they could not comprehend how a ball which had alighted on the ground, and lain still until their curiosity prompted an examination, should ‘shoot again’ of itself with such destructive force. 25 What they could not understand must be supernatural, hence the evil spirits which they had invoked against the white people had turned against themselves, and it was useless to resist them. In short, they felt the heavy hand of fate against them, and -bowed submissive to its decree. When the morning of the 27th dawned the hostile force had disappeared, taking what cattle they could find; “the sole results,” says Phelps, whom I have chiefly followed in the narration of the attack on Seattle, “of an expedition which it had taken months to perfect, and looking to the utter annihilation of the white settlers in that section of the country.” I have it from the same authority that news of the attack was received at Bellingham Bay, a hundred miles distant, in seven hours from its commencement, showing the interest taken in the matter by the tribes all along the Sound. Their combination was to depend upon the success of the movement by Leschi and Owhi, and it failed; therefore they concealed their complicity in it, and remained neutral.

Leschi, however, affected not to be depressed by the reverse he had sustained, but sent a boastful message to Captain Gansevoort that in another month, when he should have replenished his commissary department, he would return and destroy Seattle. This seeming not at all improbable, it was decided to erect fortifications sufficiently ample to prevent any sudden attack; whereupon H. L. Yesler contributed a cargo of sawed lumber with which to erect barricades between the town and the wooded hills back of it. This work was commenced on the 1st of February, and soon completed. It consisted of two wooden walls five feet in height and a foot and a half apart, filled with earth and sawdust solidly packed to make it bullet-proof. 26 A second block-house was also erected on the summit of a ridge which commanded a view of the town and vicinity, and which was armed with a rusty cannon taken formerly from some ship, and a six-pounder field-piece taken from the Active, which returned to Seattle on hearing of the attack. An esplanade was constructed at the south end of the town, in order to enable the guns stationed there to sweep the shore and prevent approach by the enemy from the water-front; clearing and road-building being carried on to make the place defensible, which greatly improved its appearance as a town.

On the 24th of February 1856, the United States steamer Massachusetts arrived in the Sound, commander Samuel Swartwout assuming the direction of naval matters, and releasing the Active from defensive service at Seattle, where for three weeks her crew under Johnson had assisted in guarding the barricades. About a month later another United States steamer, the John Hancock, David McDougall commander, entered the Sound, making the third man-of-war in these waters during the spring of 1856. The Decatur remained until June. In the mean time Patkanim had stipulated with the territorial authorities to aid them in the prosecution of the war against the hostile tribes. For every chief killed, whose head he could show in proof, he was to be paid eighty dollars, and for every warrior, twenty. The heads were delivered on board the Decatur, whence they were forwarded to Olympia, where a record was kept. 27

In April a large body of Stikines repaired to the waters of the gulf of Georgia, within easy distance of the American settlements, and made their sorties with their canoes in any direction at will. On the 8th the John Hancock, being at Port Townsend, expelled sixty from that place, who became thereby much offended, making threats which alarmed the inhabitants, and which were the occasion of a public meeting on the following day to request the governor and Commander Swartwout to send a war-steamer to cruise between Bellingham Bay and the other settlements on the lower Sound and Fuca Sea. 28 During the whole summer a feeling of insecurity and alai in prevailed, only alleviated by the cruising of the men-of- war. That they still infested these waters at midsummer is shown by the account of Phelps of the departure of the Decatur from the Sound in June, which he says was “escorted by our Indian friends, representatives from the Tongas, Hydah, Stickene, and Shineshean tribes,” until abreast of Victoria. They were glad to see the vessel depart.

In October a small party of Stikines attacked a small schooner belonging to one Valentine, killing one of his crew in an attempt to board the vessel, and severely wounding another. They were pursued by the Massachusetts, but escaped. At the same time other predatory detachments of a large party landed at different points, robbing the houses temporarily vacated by the owners, and not long afterward visited the Indian reservation near Steilacoom and carried off the potatoes raised by the reserve Indians. At the second visit of the robbers to the reservation, the Nisquallies killed three of the invaders, in consequence of which much alarm existed.

Swartwout then determined to drive them from the Sound, and overtaking them at Port Gamble on the 20th, found them encamped there in force. Wishing to avoid attacking them without sufficient apparent provocation, he sent a detachment under Lieutenant Young in a boat to request them to leave the Sound, offering to tow their canoes to Victoria, and inviting a few of the principal chiefs to visit the ship. To these proposals they returned insolent answers, gesticulating angrily at the officers and men, challenging them to come ashore and fight them, which Young was forbidden to do.

A second and larger expedition was fitted out to make another attempt to prevail upon the Indians to depart, by a display of strength united with mildness and reason, but with no better effect, the deputation being treated with increased contempt. The whole of the first day was spent in useless conciliation, when, finding his peaceable overtures of no avail, Swartwout drew the Massachusetts as close as possible to their encampment, and directly abreast, and stationed the Traveler, a small passenger-steamer running on the Sound at this time, 29 commanded for this occasion by Master’s mate Cummings, with the launch of the Massachusetts commanded by Lieutenant Forrest, both having field-pieces on board, above the Indian encampment, where their guns would have a raking fire upon it. Early in the following morning Lieutenant Semmes was ordered to take a flag of truce and reiterate his demand of the day before, pointing out to the Indians the preparations made to attack them, and the folly of further resistance. They were still determined to defy the power which they underrated because it appeared suppliant, and preparations were made for charging them and using the howitzer, which was carried on shore by the men in the launch wading waist-deep in water. Even after the landing of the men and gun they refused to consider any propositions looking to their departure, but retired to the cover of logs and trees with their arms, singing their war songs as they went.

When there could no longer be any doubt of their warlike purpose, an order was given to fire the Traveler’s field-pieces, which were discharged at the same instant that a volley blazed out of the muzzles of sixty guns in the hands of the Indians. The ship’s battery was then directed against them, and under cover of the guns, the marines and sailors on shore, led by Forrest and Semmes, charged the Indian encampment situated at the base of a high and steep hill surrounded by a dense undergrowth and by a living and dead forest almost impenetrable. The huts and property of the Indians were destroyed, although a desperate resistance was made, as futile as it was determined. After three hours the detachment returned on board ship, firing being kept up all day whenever an Indian was seen. During the afternoon a captive woman of the Stikines was sent on shore to offer them pardon, on condition that they would surrender and go to Victoria on the Massachusetts, their canoes being destroyed; but they answered that they would fight as long as one of them was left alive. However, on the morning of the 22d the chiefs made humble overtures of surrender, saying that out of 117 fighting men 27 had been killed and 21 wounded, the rest losing all their property and being out of provisions. They were then received on board the Massachusetts, fed, and carried to Victoria, whence their passage home was assured.

Swartwout in his report to the navy department expressed the conviction that after this severe chastisement the northern Indians would not again visit the Sound. In this belief he was mistaken. On the night of the 11th of August, 1857, they landed on Whidbey Island, went to the house of I. N. Ebey, shot him, cut off his head, robbed the premises, and escaped before the alarm could be given. This was done, it was said, in revenge for the losses inflicted by the Massachusetts, they selecting Ebey because of his rank and value to the community. 30

Numerous depredations were committed by them, which nothing could prevent except armed steamers to cruise in the Fuca strait and sea. 31 Expeditions to the Sound were made in January, and threats that they would have five heads before leaving it, and among others that of the United States inspector at San Juan Island, Oscar Olney. They visited the Pattie coal mine at Bellingham Bay, where they killed two men and took away their heads. They visited Joel Clayton, the discoverer of the Mount Diablo coal mines of California, living at Bellingham Bay in 1857, who narrowly escaped, and abandoned his claim on account of them. 32 Several times they reconnoitered the block-house at that place, but withdrew without attacking. These acts were retaliatory of the injury suffered in 1856. 33

Immediately on learning what had occurred in the Yakima, country, in October 1855, Indian agent Olney, at The Dalles, hastened to Walla Walla in order, if possible, to prevent a combination of the Oregon Indians with the Yakimas, rumors being in circulation that the Cayuses, Walla Wallas, and Des Chutes were unfriendly. He found Peupeumoxmox encamped on the north side of the Columbia, a circumstance which he construed as unfavorable, although by the terms of the treaty of Walla Walla the chief possessed the right for five years to occupy a trading post at the mouth of the Yakima River, or any tract in possession for the period of one year from the ratification of the treaty, which had not yet taken place. 34

Olney declared in his official communications to B. R. Thompson at this time, that all the movements of Peupeumoxmox indicated a determination to join in a war with the Yakimas. Thompson was not surprised, because in September he had known that Peupeumoxmox denied having sold the Walla Walla Valley, and was aware of other signs of trouble with this chief. 35

At this critical juncture the Hudson’s Bay Company’s officers, McKinlay, Anderson, and Sinclair, the latter in charge of the fort, in conference with Olney, decided to destroy the ammunition stored at Walla Walla to prevent its falling into the hands of the Indians; accordingly a large amount of powder and ball was thrown into the river, for which Olney gave an official receipt, relieving Sinclair of all responsibility. He then ordered all the white inhabitants out of the country, including Sinclair, who was compelled to abandon the property of the company contained in the fort, 36 valued at $37,000, to the mercy of the Indians, together with a considerable amount of government stores left there by the Indian commissioners in June, and other goods belonging to American traders and settlers.

Colonel Nesmith, of the Oregon Mounted Volunteers, on returning to The Dalles, reported against a winter campaign in the Yakima Valley, saying that the snow covered the trails, that his animals were broken down and many of his men frost-bitten and unfit for duty, so that 125 of them had been discharged and allowed to return to their homes. In the mean time the left column of the regiment had congregated at The Dalles, under Lieutenant-Colonel James K. Kelly, and Governor Curry ordered forward Major M. A. Chinn to Walla Walla, where he expected to meet Nesmith from the Yakima country.

On learning of the general uprising, while en route, Chinn concluded it impossible to enter the country, or form a junction with Nesmith as contemplated; hence he determined to fortify the Umatilla agency, whose buildings had been burned, and there await reinforcements. Arriving there on the 18th of November, a stockade was erected and named Fort Henrietta, after Major Haller’s wife. In due time Kelly arrived and assumed command, late reinforcements giving him in all 475 men.

With 339 men Kelly set forth for Walla Walla on the night of December 2d. On the way Peupeumoxmox was met at the head of a band of warriors displaying a white flag. After a conference the Indians were held as prisoners of war; the army marched forward toward Waiilatpu, and in an attack which followed the prisoners were put to death. Thus perished the wealthy and powerful chief of the Walla Wallas. 37

A desultory fight was kept up during the 7th and 8th, and on the 9th the Indians were found to have rather the best of it. 38 On the 10th, however, Kelly was reinforced from Fort Henrietta, and next day the Indians retired, the white men pursuing until nightfall. A new fortification was erected by Kelly, two miles above Waiilatpu, and called Fort Bennett.

It was now about the middle of December, and Kelly, remembering the anxiety of Governor Curry to have him take his seat in the council, began to prepare for returning to civil duties. Before he could leave the command he received intelligence of the resignation of Nesmith, and immediately ordered an election for colonel, which resulted in the elevation to the command of Thomas R. Cornelius, and to the office vacated by himself of Davis Layton. The place of Captain Bennett was filled by A. M. Fellows, whose rank in his company was taken by A. Shepard, whose office fell to B. A. Barker. With this partial reorganization ended the brief first chapter in the volunteer campaign in the Walla Walla Valley.

On the evening of the 20th Governor Stevens entered the camp, having made his way safely through the hostile country, as related in the preceding chapter. His gratitude to the Oregon regiment was earnest and cordial, without that jealousy which might have been felt by him on having his territory invaded by an armed force from another. 39 He remained ten days in the Walla Walla Valley, and finding Agent Shaw on the ground, who was also colonel of the Washington militia, a company of French Canadians was organized to act as home-guards, with Sidney S. Ford captain, and. Green McCafferty 1st Lieutenant. Shaw was directed to have thrown up defensive works around the place already selected by Kelly as the winter camp of the friendly Indians and French settlers, and to protect in the same manner the settlers at the Spokane and Colville, while cooperating with Colonel Cornelius in any movement defensive or offensive which he might make against the Indians in arms. He agreed with the Oregon officers that the Walla Walla should be held by the volunteers until the regular troops were ready to take the field, and that the war should be prosecuted with vigor.

Before leaving Walla Walla, Governor Stevens appointed William Craig his aid during, the Indian war, and directed him to muster out of the service, on returning to their country, the sixty-nine Nez Percé volunteers enrolled at Lapwai, with thanks for their good conduct, and to send their muster-rolls to the adjutant-general’s office at Olympia. Craig was directed to take measures for the protection of the Nez Percé against any incursions of the hostile Indians, all of which was a politic as well as war measure, for so long as the Nez Percé were kept employed, and flattered, with a prospect of pay in the future, there was comparatively little danger of an outbreak among them. Pleased with these attentions, they offered to furnish all the fresh horses required to mount the Oregon volunteers for the further prosecution of the campaign.

Kelly resigned and returned to Oregon, though afterward again joining his command. Stevens hastened to Olympia, where he arrived the 19th of January, finding affairs in a deplorable condition, all business suspended, and the people living in blockhouses. 40 He was received with a salute of thirty-eight guns.

The two companies under Major Armstrong, whom Colonel Nesmith had directed to scour the John Day and Des Chutes country, while holding themselves in readiness to reinforce Kelly if needed, employed themselves as instructed, their services amounting to little more than discovering property stolen from immigrants, and capturing ‘friendly’ Indians who were said to be acting as go-betweens.

During the remainder of December the companies stationed in the vicinity of The Dalles made frequent sorties in the direction of the Des Chutes and John Day countries, and were thus occupied when Kelly resigned his command, who on returning to Oregon City was received with acclamations by the people, who escorted him in triumph to partake of a public banquet in his honor, regarding him as a hero who had severed a dangerous coalition between the hostile tribes of southern Oregon then in the field and those of Puget Sound and northern Washington.

As many of the 1st regiment of Oregon Mounted Volunteers who had served in the Yakima and Walla Walla campaigns were anxious to return to their homes, Governor Curry issued a proclamation on the 6th of January, 1856, for a battalion of five companies to be raised in Linn, Marion, Yamhill, Polk, and Clackmas Counties, and a recruit of forty men to fill up Captain Conoyer’s company of scouts, all to remain in service for three months unless sooner discharged. Within a month the battalion was raised, and as soon as equipped set out for Walla Walla, where it arrived about the first of March.

Colonel Cornelius, now in command, set out on the 9th of March with about 600 men to find the enemy. A few Indians were discovered on Snake River, and along the Columbia to the Yakima and Palouse, which latter stream was ascended eight miles, the army subsisting on horseflesh in the absence of other provisions. Thence Cornelius crossed to Priest’s Rapids, and followed down the east bank of the Columbia to the mouth of the Yakima, where he arrived the 30th, still meeting few Indians. Making divers disposition of his forces, with three companies on the 31st Cornelius crossed the Columbia, intending to march through the country of Kamiakin and humble the pride of this haughty chief, when he received news of a most startling nature. The Yakimas had attacked the settlements at the Cascades of the Columbia.

Early in March Colonel Wright, now in command at Vancouver, commenced moving his force to The Dalles, and when General Wool arrived in Oregon about the middle of the month, he found but three companies of infantry at Vancouver, two of which he ordered to Fort Steilacoom, a palpable blunder, when it is recollected that there was a portage of several miles at The Cascades over which all the government stores, ammunition, and other property were compelled to pass, and where, owing to lack of transportation above, it was compelled to remain for some length of time, this circumstance offering a strong motive for the hostile Klikitats and Yakimas, whose territory adjoined, to make a descent upon it. So little attention was given to this evident fact that the company stationed at The Cascades was ordered away on the 24th of March, and the only force left was a detachment of eight men, under Sergeant Matthew Kelly, of the 4th infantry, which occupied the block-house erected about midway between the upper and lower settlements, by Captain Wallen, after the outbreak in October. 41 A wagon-road connected the upper and lower ends of the portage, and a wooden railway was partly constructed over the same ground, an improvement which the Indian war had rendered necessary and possible. On Rock Creek, at the upper end of the portage, was a sawmill, and a little below, a village of several families, with the store, or trading house, of Bradford & Co. fronting on the river, near which a bridge was being built connecting an island with the mainland, and also another bridge on the railroad. At the landing near the mouth of Rock Creek lay the little steamer Mary, the consort of the Wasco, and the first steamboat that ran on the Columbia between The Cascades and The Dalles. At the lower end of the portage lived the family of W. K. Kilborn, and near the blockhouse the family of George Griswold.

All that section of country known in popular phraseology as The Cascades, and extending for five miles along the north bank of the Columbia at the rapids, is a shelf of uneven ground of no great width between the river and the overhanging cliffs of the mountains, split in twain for the passage of the mighty River of the West. Huge masses of rock lie scattered over it, interspersed with clumps of luxuriant vegetation and small sandy prairies. For the greater part of the year it is a stormy place, subject to wind, mist, snow, and rain, but sunny and delightful in the summer months, and always impressively grand and wild.

At half-past eight o’clock on the morning of the 26th of March, General Wool having returned to California and Colonel Wright having marched his whole force out from The Dalles, leaving his rear unguarded, the Yakimas and Klikitats, having waited for this opportunity to sweep down upon this lonely spot, suddenly appeared at the upper settlement in force. The hour was early and the Mary had not yet left her landing, her crew being on their way to the boat. At the mill and the bridges men were at work, and a teamster was hauling timber from the mill.

Upon this scene of peaceful industry, in a moment of apparent security, burst the crack of many rifles, a puff of blue smoke from every clump of bushes alone revealing the hiding-places of the enemy, who had stationed themselves before daylight in a line from Rock Creek to the head of the rapids, where the workmen were engaged on the bridges. At the first fire several were wounded, one mortally. Then began the demoniacal scene of an Indian massacre, the whoops and yells of the attacking party, the shrieks of their victims as their hurried flight was interrupted by the rifle-ball, or their agonies were cut short by the tomahawk. At the mill, B. W. Brown, his wife, a girl of eighteen years, and her young brother were slain, scalped, and their bodies thrown into the stream. So well concerted and rapid was the work of destruction that it was never known in what order the victims fell. Most of the men at work on the bridges, and several families in the vicinity, escaped to bridges, store, which being constructed of logs afforded greater security than board houses.

It chanced that only an hour before the attack nine government rifles and a quantity of ammunition had been left at Bradford’s to be sent back to Vancouver. With these arms so opportunely furnished, the garrison, about forty in number, eighteen of whom were capable of defense, made preparations for a siege. The Indians, having taken possession of a bluff; or bench of land, back of and higher than the railroad and buildings, had greatly the advantage, being themselves concealed, but able to watch every movement below.

In order to counteract this disadvantage, the stairs being on the outside of the building, an aperture was cut in the ceiling, through which men were passed up to the chamber above, where by careful watching they were able to pick off an Indian now and then. A few stationed themselves on the roof, which was reached in the same way, and by keeping on the river side were able to shelter themselves, and get an occasional shot. 42 Embrasures were cut in the walls, which were manned by watchful marksmen, and the doors strongly barricaded.

While these defenses were being planned and executed, James Sinclair of the Hudson’s Bay Company, who happened to be at The Cascades, the door being opened for an instant, was shot and instantly killed by the lurking enemy. 43 A welcome sound was the `Toot, toot!’ of the Mary’s whistle, now heard above the din of war, showing that the steamer had not been captured, as it was feared-for upon this depended their only chance of obtaining succor from The Dalles.

The escape of the Mary was indeed a remarkable episode in that morning’s transactions. Her fires were out, only a part of her crew on board, and the remainder on their way to the landing, when the Indians fired the first volley. Those on shore were James Thompson, John Woodard, and James Herman. Holding a hurried consultation, Thompson and Woodard determined on an effort to save the boat, while Herman ran to the shelter of the woods and up the bank of the river. While hauling on the lines to get the boat out into the stream, the Indians pressed the two gallant men so closely that they were forced to quit their hold and seek the concealment of the neighboring thickets. The steamer was then attacked, the fireman, James Unsay, being shot through the shoulder; and the cook, a negro, being wounded, in his fright jumped overboard and was drowned. The engineer, Buckminster, having a revolver, shot an Indian, and the steward’s boy, John Chance, finding an old dragoon pistol on board, also dispatched an Indian, firing from the hurricane-deck.

In the midst of these stirring scenes the steamer’s fires were started, and Hardin Chenoweth, going up into the pilothouse and lying flat upon the floor, backed the boat out into the river, though the wind was blowing hard down stream. It was at this moment of success that the Mary’s whistles, sharp and defiant, notified the people in the store that she was off to The Dalles for help, and which sustained their spirits through the many trying hours which followed. The boat picked up the families of Vanderpool and Sheppard, who came out to her in skiffs, and also Herman of their own crew, after which she steamed rapidly up the river.

When the men on the bridges rushed into Bradford’s store three men were left upon the island, who afterward attempted to reach that refuge without being discovered by the Indians. Those on the lookout in the store could see that it was impossible, and shouted to them to lie down behind the rocks. Findlay, the first man admonished, obeyed. The Indians had now reached the island; and as Bailey, another workman who had not heard or not obeyed the caution, came running, he was mistaken for one of the enemy pursuing Findlay, and fired on, receiving a wound in the leg and arm. Both, however, sprang into the water; and although Bailey came near being carried over the falls, they reached the landing in front of the store and were hastily admitted. The third man, James Watkins, in attempting to follow, was discovered and shot through the arm. He dropped behind a rock, his friends shouting to him to lie still and they would rescue him; but they were not able to do so, and his wounds being too long neglected, he died.

In the mean time the mill, lumberyard, and several houses had been burned, and the assailants endeavored to fire the store by projecting upon it brands of pitch- wood and hot irons. They also threw stones and missiles of various kinds to dislodge the men on the roof, but the distance from which these missiles were sent rendered them comparatively harmless, the occasional fire which took in the shingles being promptly extinguished by brine from a pork barrel carefully poured on with a tin cup, no water being obtainable.

In a few hours the want of water became a fresh source of torment. Of the forty persons shut up in the small compass of the lower story of the building, four were wounded, one dead, and the majority of the whole were women and children. The only liquids in the place were two dozen bottles of ale and a few bottles of whiskey, which were exhausted in the course of the day, and all were waiting impatiently for the cover of darkness to bring some water from the river. But the Indians had reserved a new warehouse and some government property to be burned during the night to furnish light for their operations, and to prevent the escape of the besieged. In this extremity a Spokane, brought up by Mr Sinclair, volunteered to procure the needed water. Stripping himself naked, he threw himself on the slide used for loading boats, and slipping down to the river, returned with a bucketful for the wounded. The second day and night were passed like the first, no more water being procured until the morning of the 28th, when, the fires of the enemy having died out, the Spokane again ventured to the river, and this time filled two barrels, going and coming with incredible swiftness. The steamer not yet having returned, and fears being entertained of her capture, the body of Sinclair was shoved down the slide into the river by the same faithful servant.

While these scenes were being performed at the upper Cascades, the people below were also experiencing a share in the misfortunes of their neighbors. The first intimation of an attack at the blockhouse was hearing a few shots, and the shouts of men running from above warning others. Five of the little garrison of nine were in the fort at that moment. Hastening down-stairs they found one of their comrades at the door, shot through the hip. The embrasures were opened, and the cannon run out and fired at the Indians, who could be seen on a hill in front. Immediately afterward the citizens came fleeing to the fort for protection, drawing the fire of the Indians, which was returned by the soldiers until all left alive were sheltered. Firing from both sides continued for four hours, when, seeing that the Indians were about to burn a large building, Sergeant Kelly again dispersed them with the cannon. Toward night a soldier who had been wounded near the blockhouse in the morning made his way in and was rescued. During the night the Indians attempted to fire the blockhouse, without success, prowling about all night without doing much damage. During the forenoon of the 27th three soldiers made a sortie to a neighboring house, and returned safely with some provisions. In the afternoon the cannon was again fired at a large party of Indians who appeared on the Oregon side of the river, which served the purpose of scattering them, when four of the soldiers and some of the citizens sallied out to bring in the dead and wounded, and to search the deserted houses for arms and ammunition. 44

At the lower Cascades no lives were lost in the attack. On the morning of the 26th W. K. Kilborn, who owned and ran an open freight-boat on the Columbia, walked up to the lower end of the portage railroad to look for a crew of the Cascade Indians °to take his boat up the rapids to that point, but was met by a half-Spanish Indian boy whom he had known on French Prairie in the Willamette Valley, and who endeavored to show him that it was unsafe for him to be in the neighborhood, because the Yakimas and Klikitats had been about the lodges of the local Indians the night before. Kilborn took the lad with him to the office of Agent G. B. Simpson, close by, where he still persisted in imploring them to fly, telling them they were surrounded by hostile Indians on every side. At that instant came the boom of the cannon at the block-house above, and the half-breed darted down the road to give the alarm to the families below, followed by Kilborn, who was soon overtaken by a mounted man crying, “Run for your lives, they are fighting at the blockhouse! 45 On reaching his boat he found his family and that of Hamilton already on board, and instantly put off, a few men who had guns remaining to protect their property. As he was about to land for some purpose a short distance below, these men shouted to him, “Do not land; here they come!” and hearing the report of small arms, he kept on down the river, arriving at Vancouver before dark with the news of the outbreak.

In the mean time the men who had remained to protect their property were in a perilous situation. They at first entertained the idea of barricading the government wharf-boat, but having no ammunition, were obliged to abandon it. They remained on guard, however, until the Indians, having marauded their way down, began firing on them from the roof of a zinc house, which afforded a good position, when, finding it useless to remain longer, they pushed out into the river with a schooner and some bateaux lying at the landing, Thomas Pierce being wounded before attaining a safe distance, and proceeded down the river. Two men who at the first alarm fled to the mountains stole down at night and escaped in an old boat which they found at the landing to the south side of the river, where they lay hidden in the rocks until relief came.

When the news of the attack on The Cascades was received at Vancouver great consternation prevailed, it being reported that Vancouver was the objective point of the Yakimas, and there were not men enough at that post to make a good defense after sending the succor demanded at The Cascades. As there had been no communication between the upper and lower towns, the extent of the injury done at the former place could only be conjectured. The commanding officer, Colonel Morris, removed the women and children of the garrison, the greater part of the ammunition, and some other property to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fort for greater safety, while he refused arms to the captain of the volunteer home-guard, 46 in obedience to the orders of General Wool.

At an early hour of the 27th the steamboat Belle was dispatched to The Cascades, conveying Lieutenant Philip Sheridan with a detachment of the single company left by Wool at Vancouver. Meeting on the way the fugitives in the schooner and bateaux, they volunteered to return and assist in the defense of the place, and were taken on board the steamer. At ten o’clock the Belle had reached the landing at the lower end of the portage, stopping first on the Oregon side, where Sheridan and a part of his command proceeded up the river on foot to a point opposite the upper town to reconnoiter, where he learned from the Cascade Indians the state of affairs at that place, and also that the blockhouse had been attacked. Sheridan returned and landed his men on the Washington side, dispatching a canoe to Vancouver for more ammunition.

The Indians did not wait to be attacked. While the troops and howitzer were disembarking on a large sand island, Sheridan had two men shot down, and was compelled to retreat some distance from the cover of the Indians, the steamer dropping down in company. A council of war was then held, and it was decided to maintain their ground, which was done with much difficulty, through the remainder of the day, the troops not being able to advance to the relief of the block-house, although the diversion created by the arrival of troops caused a lull in the operations of the Indians against that post.

A company of thirty men was raised in Portland on the evening of the 26th, by A. P. Dennison and Benjamin Stark, aids to Governor Curry, which was augmented at Vancouver by an equal number of volunteers, and proceeded to the lower Cascades in the steamer Fashion, arriving somewhat later than the Belle, and being unable to render any assistance, for the same reason which prevented the regular troops from advancing-too numerous an enemy in front. They landed, however, and sent the steamer back, which returned next day with forty more volunteers, and a recruit of regulars, all eager for a fight.

The boat also brought a supply of ammunition from Vancouver, which being placed upon a bateau was taken up opposite the blockhouse where Sheridan intended to cover his men while they landed, with the howitzer. But just at this moment a new factor entered into the arrangement of the drama, which gave to all a surprise.

When the Mary arrived at The Dalles on the 26th, Colonel Wright had already moved from the post, and was encamped at Five-Mile Creek, so that information of the attack on the Cascades did not reach him before midnight. At daylight he began his march back to The Dalles, with 250 men, rank and file, and by night they were on board the steamers Mary and Wasco, but did not reach the Cascades before daylight of the 28th, on account of an injury to the steamer’s flues, through having a new fireman since the wounding of Lindsay on the 26th.

Just as the garrison in the store were brought to the verge of despair, believing the Mary had been captured, not knowing of Sheridan’s arrival at the lower Cascades, having but four rounds of ammunition left, and having agreed among themselves, should the Indians succeed in firing the house, to get on board a government flat-boat lying in front of Bradford’s and go over the falls rather than stay to be butchered- at this critical moment their eyes were gladdened by the welcome sight of the Hary and Wasco, steaming into the semicircular bay at the mouth of Rock Creek, loaded with troops. A shout went up from forty persons, half dead with fatigue and anxiety, as the door of their prison was thrown open to the fresh air and light of day.

No sooner had the boats touched the shore than the soldiers sprang up the bank and began beating the bushes for Indians, the howitzer belching forth shot over their heads. But although the Indians had fired a volley at the Mau as she stranded for a few moments on a rock at the mouth of the creek, they could not be found when hunted, and now not a Yakima, or Klikitat was to be seen.