The two primary elements of Montana’s grand development were gold and grasses. In a rough country of apparently few resources, the discovery of Alder gulch, resulting in $60,000,000 of precious metal, which that ten miles of auriferous ground produced in twenty years, 1 was like the rubbing of an Aladdin lamp. It drew eager prospectors from Colorado, Utah, and Idaho, who overran the country on both sides of the upper Missouri, and east and west of the Rocky Mountains, many of whom realized, to a greater or less extent, their dreams of wealth. 2 The most important discovery after Alder gulch was made by John Cowan, a tall, dark-eyed, gray-haired man from Ackworth, Georgia, who had explored for a long time in vain, and staked his remaining hopes and efforts on a prospect about half-way between Mullan’s pass of the Rocky Mountains and the Missouri River, in the valley of the Little Prickly Pear River, and called his stake the Last Chance gulch. 3 From near the ground where Helena was located, in the autumn of 1864, John Cowan took the first few thousands of the $16,000,000 which it has yielded, and returned to his native state, where he built himself a sawmill and was wisely content. 4 Hundreds of miners swarmed to Last Chance, and by the first of October the town of Helena was founded and named, and a committee appointed by citizens to lay it off in lots and draw up a set of municipal regulations suited to the conditions of a mining community. 5 From its favorable situation with regard to routes of travel, and other advantages, Helena became a rival of the metropolis of Alder gulch – Virginia City.

Following rapidly upon the discovery of Last Chance gulch were others of great richness, as the Ophir and McClellan, 6 thirty miles from Helena, 7 or the west side of the Rocky Mountains, the Confederate, east of the Missouri River and southeast of Helena, and others. 8

It will be seen that with so large a stream of gold pouring out of the country, with a diminishing population with no exports except the precious metals am a few hides and furs, and with a recklessly extravagant system of government, Montana must be brought to comparative poverty, or at all events, was no better off than other new countries which were without gold mines. This, indeed, was her condition for a number of years, from about 1869 to 1873. But this period was not lost upon its permanent population. These who owned quartz mines and mills, and who had not found them remunerative by reason of defects in machinery or ignorance of methods, took time to right themselves, or found others willing to take the property off their hands at a discount, and make improvements. Those who owned placer claims were driven to construct ditches and flumes whereby the dry gulches and the creek-beds could be mined. The settlers on land claims began to realize that agriculture could be made to pay, whenever a railroad came near enough to carry away the surplus of their fields But the men who were not injured or in any way put back by this period of silent development were the stock-raisers. Their only enemy was the Indian, and him they warned off with rifles. Stock raising in Montana was carried on, as I have shown in a previous chapter, by the Indian traders, before mines were discovered. It cropped up, accidentally, through the trading system, and the practice of buying two worn-out animals of immigrants to Oregon for one fresh one, the two being fit the next year to exchange for four. It was found that the grasses of the country, from the mountaintops to the river margins, were of the most nutritious character; that although the winters were cold, cattle seldom died. The natural adaptability of the county to stock-growing was indicated by the native animals, the mountain sheep, the buffalo, and the wild horse. 9 The sight of the large herds, accumulated by trade, and enlarged annually by natural increase, pointed out an easy and speedy means of acquiring wealth – easier than agriculture and surer than mining. 10 Cattle raising became a great and distinctive business, requiring legislation, and giving some peculiar features to the settlement of the country. 11

W. H. Raymond is said to have been the first drive a herd to the Union Pacific railroad for shipment to the east, and this he did in 1874 without loss.

The only danger to the welfare of the country, from the prominence taken by this business, is that the cattle-owners will continue more and more to oppose themselves to settlement. This they cannot do as successfully in Montana as they have done in Texas, where they have taken possession of the springs and watercourses by the simple preemption of a quarter section of land where the spring occurs. As settlers must have access to water and timber, to control the supply is to drive them away from the region. But in Montana there is a greater abundance of water, and timber also, and consequently not the same means of excluding farmers. Doubtless efforts will be made to obtain the actual ownership of large bodies of land, which the government wisely endeavors to prevent.

The falling-off in the yield of the mines forced development in other directions, so that by the time Montana had railroad connection with eastern markets it was prepared to furnish exports as well as to pay for importing. In 1879, three years before the railroad reached Helena, the farmers of Montana produced not less than $3,000,000 worth of agricultural products, 12 and were supplied with the best labor-saving machinery. They lived well, and were often men of education, with well stored book shelves, even while still occupying the original farm-house built of logs. By the laws of Montana a homestead of the value of $2,500 was exempt from execution and sale. Experience has shown that the grasshopper is the worst, and almost the only, enemy that the agriculturist dreads. This pest appears to return annually for a period of three or four years, when it absents itself for an equal length of time. No complete destruction of crops has ever occurred, their visitations being intermittent as to place – now here, now there; and grain-farmers agree that while the yield and the prices remain as good as they have been, they can support the loss of every third crop. But it is probable that in time the more general cultivation of the earth will be a check, if not destruction, to the Grasshopper.

But whatever the advantages of Montana to the agriculturalist, stock-raiser, or manufacturer of the present or the future – and they are many – it is and must remain preeminently a mining country. A reaction toward an increased production of the precious metals began in 1878, the silver yield being in excess of the gold. 13

Many phenomena are brought forward to account for the climate of Montana, such as the isothermal lines, the chinook wind, and the geysers of Yellowstone park, all of which influences are doubtless felt; but to the lower altitude of the country, as compared with the territories lying south, much of its mildness of climate must be ascribed. Latitude west the Rocky Mountains does not affect climate as it does to the east of that line; nor does it account for temperature to any marked extent on the eastern slope of the great divide, for we may journey four hundred miles north into the British possessions, finding flourishing farms the whole distance; and it is a curious fact that the Missouri River is open above the falls, in Montana, four weeks before the ice breaks up in the Iowa frontier. In all countries seasons vary, with now and then severe winters or hot summers. A great snowfall in the Montana mountains every winter is expected and hoped for. Its depth through out the country is graded by the altitude, the valleys getting only enough to cover the grass a few inches, and for a few days, when a sudden thaw, caused by the warm chinook, carries it off. Occasionally a wind from the interior plains, accompanied by severe cold and blinding particles of ice rather than snow, which fill and darken the air, brings discomfort to all, and death to a few. Such storms extend from the Rocky Mountains to east of the Missouri River; from Helena to Omaha.

The mean temperature of Helena is 44°, four degrees higher than that of Deer Lodge or Virginia City, these points being of considerable elevation about the valleys, where the mean temperature is about 48°. With the exception of cold storms of short duration, the coldest weather of winter may be set down at l9° below zero, and the warmest weather of summer at 94°. June is rainy, the sky almost the whole of the rest of the year being clear, and irrigation necessary to crops. The bright and bracing atmosphere promotes health, and epidemics are unknown. Violent storms and atmospheric disturbances are rare. 14

The first settlers of Montana had doubts about the profits of fruit culture, which have been dispelled by experiments. Apples, pears, plums, grapes, cherries, currants, gooseberries, raspberries, blackberries, and strawberries bear abundantly, and produce choice fruit at an early age. 15 In the Missoula Valley cultivated strawberries still ripen in November. At the county fair in 1880 over a dozen varieties of standard apples were exhibited, with several of excellent plums and pears. Most of the orchards had been planted subsequently to 1870, and few were more than six years old. Trees of four years of age will begin to bear. At the greater altitude of Deer Lodge and Helena fruit was at this period beginning to be successfully cultivated; but fruit-growing being generally under-taken with reluctance in a new country, it is probable, judging by the success achieved in Colorado, that the capacity of Montana for fruit-culture is still much underrated. All garden roots attain a great size, and all vegetables are of excellent quality. Irrigation, which is necessary in most localities, is easily accomplished, the country in general being traversed by many streams. For this reason irrigation has not yet been undertaken on the grand scale with which it has been applied to the arid lands a few degrees farther south. The desert land act, designed to benefit actual settlers, has been taken advantage of to enrich powerful companies, which by bringing water in canals long distances were able to advance the price of land $10 or $15 per acre. The timber culture act was made use of in the same way to increase the value of waste land. 16 Doubtless the lands thus benefited were actually worth the increased price to these who could purchase them, but the poorer man whom the government designed to protect was despoiled of his opportunity to build up a home by slow degrees by the desire of richer men to increase their fortunes indefinitely. An effort is now being made to induce the government to undertake water storage for the improvement of desert lands.

Citations:

- Strahorn’s Montana, 8; Barrows’ Twelve Nights, 239.[

]

- Among the discoveries of 1864 was the Silver Bow, or Summit Mountain district, on the head waters of Deer Lodge River. It was found in July by Bud. Barker, Frank Ruff, Joseph Eater, and James Ester. The name of Silver Bow was given by these discoverers, from the shining and beautiful appearance of the creek, which here sweeps in a crescent among the hills. The district was 12 miles in length, and besides the discovery claim or gulch, there were 21 discovered and worked in the following 5 years, and about as many more that were worked after the introduction or water ditches in 1869. The men who uncovered the riches of Silver Bow district were, after the original discoverers:

Total number of claims in the district in 1869 was 1,007. There were at this time 7 ditches in the district from 1 to 20 miles in length, aggregating 53 miles, with a total capacity of 3, 100 inches of water, constructed at a cost of $106,000. Deer Lodge New Northwest Nov. 12, 1869.[

]

- R. Stanley of Attleborough, Nuneaton, England, was one of the discovery party. John Crab and D. J. Miller were also of the party. They had come from Alder gulch, where no claims were left for them. They encamped in a gulch where Helena was later placed, but not finding the prospect rich, set out to go to Kootenai. On Hellgate River they met a party returning thence, who warned them not to waste their time. So they turned back, and prospected on Blackfoot River, and east of the mountains on the Dearborn and Maria rivers, until they found themselves once more in the gulch on the Prickly Pear, which they said was “their last chance.” It proved on further trial to be all the chance they desired. Stanley, in Helena City Directory, 1883-4,47-8.[

]

- John Sloss, killed by Indians in 1866, on the Dry fork of Cheyenne River, is also called one of the discoverers of Last Chance gulch.[

]

- George P. Wood, says the Helena Republication Sept. 20, 1866, was the only one of the committee who ever attempted to discharge the duties of his office – an unpaid and thankless service. If Helena shows defects of grade and narrowness of streets in the original plan, it could not be otherwise in a town hastily settled, without surveys, and necessarily conforming to the character of the ground. And, as has frequently been the case, a spring of water determined the question of the first settlement. After the Helena Water Company had constructed a system of water pipes leading to the more level ground, which it did in 1865-6, the town rapidly followed in that direction. A ditch leading from Ten Mile Creek to the mines below town caused a spreading-out in that direction. Hence the irregularities in the plan of Montana’s capital.[

]

- Named after John L. McClellan, the discoverer. Blackfoot City was located on Ophir gulch, discovered by Bratton, Pemberton, and others, in May 1865. In 1872 it had been abandoned to the Chinese.[

]

- Helena was located on Dry gulch, which could not be worked until ditches were constructed. Oro Fino and Grizzly gulches were joined half a mile above the town, forming the celebrated Last Chance. Nelson’s gulch headed in the mountains, and ran into Ten Mile Creek. South from them were a number of rich gulches running into Prickly Pear River. Helena Republican, Sept. 15, 1866.[

]

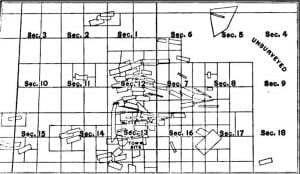

- For 150 miles north and south of Helena, and 100 east and west of the same point, mines of exceeding richness were discovered in 1865 and 1866. First Chance gulch, a tributary of Bear gulch, in Deer Lodge County, yielded nearly $1,000 a day with one sluice and one set of hands. New York gulch and Montana bar, in Meagher County, were fabulously productive. Old Helena residents still love to relate that on the morning of the 18th of August, 1866, two wagons loaded with a half ton each of gold, and guarded by an escort of fifteen men, deposited their freight at Hershfeld & Co.’s banks on Bridge street, this treasure having been taken from Montana bar and Confederate gulch in less than four months, by two men and their assistants, and Helena bankers are still pleased to mention that in the autumn of 1866 a four-mule team drew two and a half tons of gold from Helena to Benton, for transportation down the Missouri River, most of which came from these celebrated mines in one season, and the value of which freight was $1,500, 000. The train was escorted by F. X. Beidler and aids. The treasure belonged to John Shineman, A. Campbell, C. J. Friedrichs, and T. Judson. Helena Republican, Sept. 1. 1866; W. A. Clarke, in Strahorn’s Montana, 9.

As a memento of early days in Montana, I will cite here some of the nuggets which rewarded the miner’s toil in the placer-mining period. In Brown gulch, 5 miles from Virginia City, the gold was coarse, and nuggets of 10 oz. or more were common. Virginia and Helena Post, Oct. 9, 1866. In 1867 a miner named Yager found in Fairweather gulch, on J. McEvily’s claim, a piece of gold, oblong in shape, with a shoulder at one end, and worn smooth, weighing 15 lbs 2 oz. Virginia Montana Post, May 18, 1867. From McClellan’s gulch, on the Blackfoot River, $30,000 was taken from one claim in 11 days, by 5 men. From a claim, No. 8, below Discovery claim, on the same gulch, $12,584 was taken out in 5 days. The dirt back of Blackfoot City paid from 20 c. to $140 to the pan. Helena Republican, Aug. 26, 1866. From Nelson’s gulch, at Helena, were taken a nugget worth $2,093, found on Maxwell, Rollins, & Co.’s claim, and one worth $1,650 from J. H. Rogers’ claim. From Deitrick & Brother’s claim, on Rocker gulch, one worth $1,800; and on Tandy’s claim three worth $375, $475, and $550, respectively. Almost every claim had its famous nugget. Mining ground was claimed as soon as discovered, and prospectors pushed out in every direction. New placers were found from the Bitterroot to the Bighorn River, but none to excel or to equal these of 1863 and 1864.

The discovery of quartz-ledges was contemporaneous with the discovery of Bannack placers in 1862. A California miner remarked, in 1861, that he counted 7 quartz lodes in one mountain. S. F. Bulletin, Aug. 28, 1861. The first lode worked was the Dakota, which was a large, irregularly shaped vein carrying free gold, varying from three to eight feet in thickness, trending northwest and southeast, dipping to the northeast, and situated in a bald hill near Bannack. Its owners were Arnold & Allen, who proceeded to erect a mill out of such means as were at hand, the iron and much of the wood being furnished by the great number of wagons abandoned at this point by the Salmon River immigrants before spoken of. Out of wagon-tires, in a common blacksmith’s forge, were fashioned six stamps, weighing 400 pounds each. The power used was water, and with this simple and economical contrivance more gold was extracted than with some of ten times the cost introduced later.

The first steam quartz-mill was put up in Bannack in 1863, by Hunkins. Walter C. Hopkins placed a steam-mill on No. 6 Dakota, in August 1866. The Bullion Mining Company of Montana owned a mill in 1866, with. 3 Bullock crushers, and placed it on the New York ledge, Keyser manager. The East Bannack Gold and Silver Mining Company owned a mill in 1866, placed on the Shober ledge; managed by David Worden. The Butterfield mill, and Kirby & Clark mill, were also in operation near Bannack in 1866; and N. E. Wood had placed a Bullock patent crusher on Dakota No. 12, for the New Jersey Company.

The subject of transportation in Montana is one full of interest and even of romance. Taking up the recital at 1804, there was at this time no settled plan of travel or fixed channel of trade. There had been placed upon the Missouri a line of steamers intended to facilitate immigration to Idaho, which was called the Idaho Steam Packet Company. The water being unusually low, or rather, not unusually high, only 2 of the boats reached Fort Benton – the Benton and Cutter, The Yellowstone landed at Cow Island, and the Effie Deans at the mouth of Milk River. The Benton, which was adapted to upper-river navigation, brought a part of the freight left at other places down the river, by other boats, to Fort Benton; but the passengers had already been set afoot in the wilderness to make the best of their way to the mines. Overland Monthly, ii. 379; and a large portion of the freight had to be forwarded in small boats. At the same time there was an arrival at Virginia City of 200 or 300 immigrants daily by the overland wagon-route, as well as large trains of freight from Omaha. Boise City Statesman, Jan. 21, 1865; Portland Oregonian, Sept. 14, 1804. In 1865 there were 8 arrivals of steamboats, 4 of which reached Benton, the other 4 stopping at the mouth of Maria River. In this year the merchants of Portland, desirous of controlling the trade of Montana, issued a circular to the Montana merchants proposing to make it for their interest to purchase goods in Portland and ship by way of the Columbia River and the Mullan road, with improvements in that route of steamboat navigation on Lake Pend d’Oreille, and S. G. Reed of the O. S. K. Company went east to confer with the Northern Pacific R. R. Company. In 1800 some progress was made in opening this route, which in the autumn of that year stood as follows: From Portland to White Bluffs on the Columbia by the O. S. N. Company’s boats; from White Bluffs by stage-road to a point on Clarke fork, where Moody & Co. were building a steamboat 110 feet long by 20 feet beam, called the Mary Moody, to carry passengers and freight across the lake and up Clarke fork to Cabinet landing, where was a short portage and transfer to another steamboat which would carry to the mouth of the Jocko River, after which land travel would again bo resorted to. The time to Jocko would be 7 or 8 days, and thence to the rich Blackfoot mines was a matter of 50 or 60 miles. It was proposed to carry freight to Jocko in 17 days from Portland at a cost of 13 cents per pound. From Jocko to Helena was about 120 miles, and from Helena to Virginia about 90. By this route freight could arrive during half the year, while by the Missouri River it could only come to Benton during a period of from 4 to 6 weeks, dependent upon the stage of water. The lowest charges by Missouri steamer, in 1806, were 15 cents to Benton for a large contract, ranging upward to 18 and 21 cents per pound, or $360 and $420 per ton to the landing only, after which there was the additional charge of wagoning, at the rate of from 5 to 8 cents, according to whether it reached Benton or not, or whether it was destined to Helena or more distant points. Sacramento Record-Union, May 7, 1800. San Francisco merchants offered for the trade of Montana, averring that freight could be laid down there at from 15 to 20 cents per pound overland. S. F. Alta, May 7 and Aug. 11, 1800. Chicago merchants competed as well, taking the overland route from the Missouri. Meanwhile Montana could not pause in its course, and took whatever came. In 1800 there was a large influx of population, and a correspondingly large amount of freight coming in, and a considerable flood of travel pouring out in the autumn. The season was favorable to navigation, and there were 31 arrivals of steamboats, 7 boats being at Fort Benton at one time in June. One, the Marion, was wrecked on the return trip. These boats were built expressly for the trade of St Louis. They brought up 2,000 passengers or more, and 6,000 tons of freight valued at $2,000,000. The freight charges by boat alone amounted to $2,000,000. Some merchants paid $100,000 freight bills; 2,500 men, 3,000 teams, 20,000 oxen and mules were employed conveying the goods to different mining centers. Helena Republican, Sept. 15, 1866; Virginia and Helena Post, Sept. 29 and Oct. 11, 1866; Goddard’s Where to Emigrate, 125. Large trains were arriving overland from the east, both of immigrants and freight, from Minnesota, and conducted by James Fisk, the man who conducted the Minnesota trains of 1862 and 1863, by order of the government, for the protection of immigrants. The plan of the organization seems to have been to make the immigrants travel like a military force, obeying orders like soldiers and standing guard regularly. From Fort Ripley, Fisk took a 12-poond howitzer with ammunition. Scouts, flankers, and train-guards were kept on duty. These precautions were made necessary by the recent Sioux outbreak in Minnesota. The officers under Fisk were George Dart, 1st assist: S. H. Johnston, 2d assist and journalist; William D. Dibb, physician; George Northrup, wagon-master; Antoine Frenier, Sioux interpreter; R. D. Campbell, Chippewa interpreter. The guard numbered 50, and the wagons were marked ‘U. S.’ Colonels Jones and Majors, majors Hesse and Hanney, of the Oregon boundary survey, joined the expedition. The wagon master, Northrup, and 2 half-breeds deserted on the road, taking with them horses, arms, and accoutrements belonging to the government. The route was along the north side of the Missouri to Fort Benton, where the expedition disbanded, having had no trouble of any kind on the road, except the loss of Majors, who was, however, found, on the second day, nearly dead from exhaustion, and the death of an invalid, William H. Holyoke, after reaching Prickly Pear River. In 1864 about 1,000 wagons arrived at Virginia by the central or Platte route. In 1865 the immigration by this route was large. The roundabout way of reaching the mines from the east had incited J. M. Bozeman to survey a more direct road to the North Platte, by which travel could avoid the journey through the South pass and back through cither of the passes used in going from Bannack to Salt Lake. The road was opened and considerably travelled in 1866, but was closed by the Indian war in the following year, and kept closed by order of the war department for a number of years. In July 1866 a train of 45 wagons and 200 persons passed over the Bozeman route, commanded by Orville Royce, and piloted by Zeigler, who had been to the starts to bring out his family. Peter Shroke also travelled the Bozeman route. Several deaths occurred by drowning at the crossing of rivers, among them Storer, Whitson, and Van Shimel. One train was composed of Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin people. In the rear of the immigration were freight-wagons, and detached parties to the number of 300. Virginia Montana Post, July 12, 1860.

A party of young Kentuckians who left home with Gov. Smith’s party became detached and wandered about for 100 days, 35 of which they were forced to depend on the game they could kill. They arrived at Virginia City destitute of clothing, on the 13th, 14th, and 15th of December. Their names were Henry Cummings and Benjamin Cochran of Covington; Austin S. Stuart, Frank R. Davis, A. Lewis, N. T. Turner, Lexington; Henry Yerkes, Danville; P. Sidney Jones, Louisville; Thomas McGrath, Versailles; J. W. Throckmorton and William Kelly of Paris. Virginia and Helena Post, Dec. 20, 1866.

The Indians on the Bozeman route endeavored to cut off the immigration. Hugh Kikendall’s freight train of 40 six-mule teams was almost captured by them, ‘passing through showers of arrows.” It came from Leavenworth, arriving in September. Joseph Richards conducted 52 wagons loaded with quartz machinery from Nebraska City to Summit district, for Frank Chistnut and had but 1 mule stolen. J. H. Gildersleeve, bringing out 3 wagon loads of goods for himself, lost 9 horses by the Indians near Fort Reno. J. Dilmorth brought out 8 loaded wagons from Leavenworth; J. H. Marden 5, from Atchinson, for Brendlinger, Dowdy, and Kiskadden of Montana. J. P. Wheeler brought out 6 wagons loaded at the same place for the same firm. F. R. Merk brought 13 wagons from Lawrence, Kansas. Alfred Myres 7 wagons, for Gurney & Co. D. and J. McCain brought 11 wagons from Nebraska City, loaded with flour, via Salt Lake. E. R. Horner brought out 8 wagons loaded at Nebraska City for himself. The Indians killed 2 men, and captured 5 mules belonging to the train. William Ellinger of Omaha brought out 4 wagons. A. F. Weston of St Joseph, Missouri, brought out 8 wagons, loaded with boots and shoes, for D. H. Weston, of Gurney & Co. Thomas Dillion left Plattsmouth, Nebraska, for Virginia City, May 26th, with 23 wagons for Tootle, Leach, & Co.; Dillon was killed by the Indians on Cedar fork, near Fort Reno. A train of 19 wagons belonging to C. Beers and Vail & Robinson had 90 mules captured on the Bighorn River. The wagons remained there until teams could be sent to bring them in. Phillips & Freeland of Leavenworth arrived with 14 loaded wagons in September; and 5 wagons for Bernard & Eastman. R. W. Trimble brought out 17 wagons for Hanauer, Solomon, & Co. Nathan Floyd of Leavenworth, bringing 5 wagons loaded with goods for himself, was killed by the Indians near Fort Reno, and his head severed from his body. A train of 26 wagons, which left Nebraska City in May with goods for G. B. Morse, had 2 men killed near Fort Reno, on Dry fork of Cheyenne River. Pfouts & Russell of Virginia City received 40 tons of goods in 17 wagonloads, this season. At the same time pack-trains from Walla Walla came into Helena over the Mullan road, which had been so closed by fallen timber, decayed or lost bridges, and general unworthiness as to be unfit for wagon travel, bringing clothing manufactured in San Francisco, and articles of domestic production. Heavy wagon trains from Salt Lake, with flour, salt, bacon, etc., arrived frequently. So much life, energy, effort, and stir could but be stimulating as the mountain air in which all this movement went on. The freighter in these days was regarded with far more respect than railroad men of a later day. It required capital and nerve to conduct the business. Sometimes, but rarely, they lost a whole train by Indians, or by accident, as when Matthews, in the spring of 1866, lost a train by the giving way of an ice jam in the Missouri, which flooded the bottom where he was encamped, and carried off all his stock. Montana Scraps, 4

I have attempted to give some idea of the getting to Montana. But many of these who came in the spring, or who had been a year or more in the country, returned in the autumn. The latter class availed themselves of the steamers, which took back large numbers, at the reasonable charge of $60 and $75. The boats did not tarry at Benton, but dropped down the river to deeper water, and waited as long as it would be safe, for passengers. A small boat, called the Miner, belonging to the Northwest Fur Company, was employed to carry them from Benton to the lower landings. The Luella was the boat selected to carry the 2½ millions of treasure from Confederate gulch, of which I have before spoken. She left Benton on the 16th of August, and was 7 days getting down to Dophan rapids, 250 miles below, where it was found necessary to take out the bulk-head, take off the cabin doors, and land the passengers and stores, to lighten her sufficiently to pass her over the rapids. Helena Republican, Aug. 30, 1866. What an opportunity for Indians or road agents! She escaped any further serious detention, passing Leavenworth Oct. 8th, and St Joseph Oct. 10th, as announced in the telegraphic despatches in Virginia and Helena Post, Oct. 16th. The expedient was resorted to of building fleets of mackinaw boats, such as were used by the fur companies, and either selling them outright to parties, or sending them down the river with passengers. Riker and Bevins of Helena advertised such boats to leave September 10th, in the Republican of the 1st. J. J. Kennedy & Co. advertised ‘large-roofed mackinaw’ to Omaha, ‘with comfortable accommodations and reasonable charges;’ also boats for sale carrying 10 to 30 men. Jones, Sprague, & Nottingham were another mackinaw company; and W. H. Parkeson advertised ‘bullet proof’ mackinaws. That was a recommendation, as bullets were sometimes showered upon these defenseless craft from the banks above. Three men, crew of the first mackinaw that set out, were killed by Indians. Another party of 22 were fired upon one morning as they were about to embark, and 2 mortally wounded, Kendall of Wisconsin and Tupsey on New York, who were left at Fort Sully to die. In this and subsequent years many home returning voyages were intercepted and heard of no more. The business in the autumn of 1866 was lively. Huntley of Helena established a stage line to a point on the Missouri 15 miles from that place, whence a line of mackinaw boats owned by Kennedy, carried passengers to the falls in 25 hours. Here a portage was made in light wagons. On the 3d day they reached Benton, where a final embarkment took place. At least 1½ millions in gold dust left Benton on mackinaws in one week. One boat carried passengers and $50,000 in treasure. A party of 45, which down on the steamer Montana, carried $100,000. A party of Maine men carried away $50,000 and Munger of St. Louis $25,000. Professor Patch of Helena, with a fleet of 7 large boats and several hundred passengers, carried away $1,000,000. They were attacked above Fort Rice by 300 Indians whom they drove away. These home returning miners averaged $3,000 each, which I take to be the savings of a single short season.

A new route was opened to the Missouri in 1866, by mackinaws down the Yellowstone. A fleet of 16 boats, belonging to C. A. Head, carried 250 miners from Virginia City. It left the Yellowstone canon Sept. 27, and travelled to St Joseph, 2,700 miles, in 28 days. St. Joseph Herald, Nov. 8, 1866. The pilot boat of this fleet was sunk at Clarke fork on the Yellowstone, with a loss of $2,500. The expedition had in all $500,000 in gold dust.

It was projected to open a new wagon-route from Helena to the mouth of the Musselshell River, 300 miles below Benton. The distance by land, in a direct line, was 190 miles. The Missouri and Rocky Mountain Wagon Road and Telegraph Company employed 20 men under Miles Courtwright to lay it out, in the autumn, to Kerchival City, a place which is not now to be found on map. The object was to save the most difficult navigation and open up the country. S. F. Call, Jan. 12, 1866; Virginia and Helena Post, Nov. 8, 1866. The Indians interrupted and prevented the survey of this road. An appropriation was made by congress in 1865 for the opening of a road from the mouth of the Niobrara River, Nebraska, to Virginia City, and Col. J. A. Sawyer was appointed superintendent. Helena Republican, Aug. 18, 1866. This would have connected with the Bozeman route. Its construction through the Indian country was opposed by Gen. Cook.

Such were the conditions of trade and travel in Montana in 1866. There were local stage lines in all directions and better mail facilities than the countries west of the Rocky Mountains had enjoyed in their early days. The stage line east of Salt Lake had more or less trouble with the Indians for 10 or 15 years. In 1867 travel was cut off and the telegraph destroyed. The Missouri, treacherous and difficult as it was, proved the only means of getting goods from the east as early as May or June. The Waverley arrived May 25th, with 150 tons of freight and as many passengers. Silver City Avalanche, June 15, 1867. She was followed by 38 other steamboats, with freight and passengers; and in the autumn there was the same rush of returning miners that I have described, carrying millions with them out of the treasure deposits of the Rocky Mountains. The Imperial, one of the St. Louis fleet, had the following experience: She started from Cow Island, where 400 passengers, who had come down from Benton on mackinaws, took passage Sept. 18th with 15 days’ provisions. She readied Milk River Oct. 4th, out of supplies in the commissary department. The river was falling rapidly, and this, with the necessity for hunting, caused the boat to make but 20 miles in one entire week. The Sioux killed John Arnold, a miner from Blackfoot, and a Georgian, while out hunting. The passengers were compelled to pull at ropes and spars to help the boat along. Every atom of food was consumed, and for a week the 400 subsisted on wild meat; then for three days they had nothing. At Fort Union they obtained some grain. Still making little progress, they arrived at Fort Sully Nov. 14th, the weather being cold and ice running. At this place 14 of the passengers took possession of an abandoned mackinaw boat, which they rigged with a sail, and started with it to finish their voyage. They reached Yankton, Dakota, Nov. 22d, where they took wagons to Sioux City, and a railroad thence. The Imperial was at last frozen in the river and her passengers forced to take any and all means to get away from her to civilization. Virginia Montana Post, Jan. 18, 1868. A train of immigrants came over the northern route this year, Capt. P. A. Davy, commanding; Major William Cahill, adjutant; Capt. J. D. Rogers, ordnance and inspecting officer; Capt. Charles Wagner, A. D. C; and captains George Swartz, Rosseau, and Nibler. The train was composed of 60 wagons, 130 men, and the same number of women and children. Captain Davy had loaded his wagons so heavily that the men, who had paid their passage, were forced to walk. They had a guard of 100 soldiers from Fort Abercrombie. St Cloud Journal, Aug. 10, 1867. This train arrived safely. The fleet down the Yellowstone this year met with opposition from the Indians just below Bighorn River, and had one man, Emerson Randall, killed. There were 67 men and 2 women in the party, who reached Omaha without further loss.

A movement was made in 1873 to open a road from Bozeman to the head of navigation on the Yellowstone, and to build a steamer to run thence to the Missouri; also to get aid from the government in improving the river. The first steamboat to ascend the river any distance was the Key West, which went to Wolf rapids in 1873, the Josephine reaching to within 7 miles of Clarke fork in 1874. Lamne built the Yellowstone, at Jeffersonville, Indiana, in 1876. She was sunk below Fort Keogh in 1879. In 1877, 14 different boats ascended above the Bighorn, and good were wagoned to Bozeman. It was expected to get within 150 miles of Bozeman the following year.

In 1868, 35 steamers arrived at Benton with 5,000 tons of freight. One steamer, the Amelia Poe, was sunk 30 miles below Milk River, and her cargo lost. The passengers were brought to Benton by the Bertha. This year the Indians were very hostile, killing wood-cutters employed by the steamboat company, and murdering hunters and others. There was also a sudden dropping in prices, caused by the Northwest Transportation Company of Chicago, which dispatched its boats from Sioux City, competing for the Montana trade, and putting freight down to 8 cents a pound to Benton, in gold, or 2 cents in currency. This caused the St Louis merchants to put freights down to 8 cents. Montana Democrat. The president of the Chicago Company was Joab Lawrence, an experienced steamboat man, with Samuel Do Bow agent. This reduction effectually cut off competition on the west side of the Rocky Mountains, and rendered the Mary Moody and the Mullan road of little value to the trade of Montana. This accounts, in fact, for the apathy concerning that route. For a short period there was a prospect of the Pend d’Oreille Lake route being a popular one, but it perished in 1868. Overland Monthly, ii. 383-4. In 1874 delegate Maginnis introduced a bill in congress for the improvement of the Mullan road, which failed, as all the memorials and representations of the Washington legislature had failed. There was a new era begun in 1869, when the Central and Union Pacific railroads were joined. There were still 28 steamers loaded for Montana, 4 of which were burned with their cargoes before leaving the levee at St Louis. This fleet was loaded before the completion of the road. Had the Bozeman route been kept open there would have been communication with the railroad much earlier; but since the government had chosen to close it, and to keep a large body of hostile Indians between the Montana settlements and the advancing railroad, it was of no use before it reached Ogden and Corinne. The advent of the railroad, even as near as Corinne, caused another reduction from former rates to 8 cents per pound currency from St Louis and Chicago by rail, to which 4 cents from Corinne to Helena was added. The boats underbid, and 24 steamers brought cargoes to Fort Benton, 8 of which belonged to the Northwest Company; but in 1870 only 8 were thus employed; in 1871, only 6; in 1872, 12; and in 1873 and 1874, 7 and 6. Conspicuous among the freighting companies which made connections with railroad points was the Diamond railroad, George B. Parker manager, which in 1880 absorbed the Rocky Mountain Despatch Company, shippers from Ogden, and made its initial point Corinne. Corinne Reporter, May 21, 1870. When the Northern Pacific rail road reached the Missouri at Bismarck, the Diamond railroad made connection with it by wagon train, thus compelling the U. P. R. B. to make special rate to Ogden for Montana, the charge being $1.25 per cwt. without regard to classification, when Utah merchants were being charged $2.50 for the same service Montanians chose to sustain the northern route. Deer Lodge New Northwest Aug. 22, 1874. In 1879 there were 1,000 teams on the road between Bismarck and the Black Hills, and Montana merchants were unable to get their goods brought through in consequence of this diversion of transportation. Helena Herald, Oct. 18, 1879. Many efforts were made from time to open a wagon road to the east by way of the Yellowstone, which failed for reasons that appear in the history of Indian affairs. These difficulties only disappeared at the N. P. R. R. advanced. Steamboat trade had a revival after the falling off mentioned above. In 1877, 25 steamers arrived at Benton with 5,283 tons of freight. Small companies engaged in steam boating later. The completion of the Northern Pacific placed transportation on a basis of certainty, and greatly modified its character.[

]

- I find frequent references to the black horse of Montana, which is described as a beautiful and fleet creature, the last of which has disappeared from the plains. In the Missoula Pioneer, June 29, 1872, is an animated account of the manner of pursuing and taking them by the Indians – the Indian sentinels, the flying blackbird, the clouds of dust which helped to betray the creatures to their capture or their death, for they often died in the struggle, strangled by the lasso, and exhausted with running and with dread – and of the killing of the last of the race, a mare, by the writer. She was killed for stealing, or enticing away other horses. ‘She stood 14 hands high, glossy black, not one white hair, but two, one on the edge of each sphere of her brain; her mane twisted in hard heavy locks, of which I keep two, each 3½ feet long; her neck and limbs clean, hard, wiry; her hoofs concave, thin, hard, and steep; her sharp, oblique shoulder and wither, straight, delicate face, and right-angled upper lids – soon told why she was so fast and spirited.’[

]

- John Grant owned, in 1866, 4,000 head of cattle and between 2,000 and 3,000 Indian horses, and was worth $400,000. H. Ex. Doc, 45, 20, 38th cong. 1st sess.[

]

- Montana Cattle Ranching[

]

- Wheat 400,000 bushels, oats 600,000, barley 60,000, corn 12,000, vegetables 500,000, hay 65,000 tons. Strahorn’s Montana, 90. In 1880 Montana produced 470,000 bushels of wheat, 900.000 of oats, 40,000 of barley. Farmers’ Resources of the Rocky Mountains, 110.[

]

- The most famous silver districts were those of Butte in Silver Bow, Philadelphia in Deer Lodge, Glendale in Beaverhead and Jefferson in Jefferson County. In May 1864 Charles Murphy and William Graham discovered the Black Chief lode, which they called the Deer Lodge, in the Silver Bow district. Soon after, G. O. Humphreys and William Allison discovered the Virginia, Moscow, and Missoula leads. The Black Chief was an enormous ledge, extending for miles. Copper also was found in the foothills, and soon a camp of seventy-five or a hundred men had laid the foundations of Butte at the head of Silver Bow Creek. But they had neither mills nor smelters, and but for the finding of good placer diggings by Felix Burgoyne, would have abandoned the place. In 1866 a furnace for smelting copper was erected by Joseph Ramsdall, William Parks, and Porter Brothers. In1875, the time having expired when the discoverers could hold their claims without performing upon them an amount of labor fixed by a law of congress, and no one appearing to make these improvements, W. L. Farlin relocated thirteen quartz claims southwest from Butte, erected a quartz-mill, and infused a new life into the town. Five years afterward a substantial city, with five thousand inhabitants, occupied the place of the former shabby array of miners’ cabins. From twenty quartz-mills, arastras, roasters, and smelters, $l,500,000 was being annually turned out, and the thousands of unworked mines in the vicinity could have employed five times that number. The Alice mine, which begun with a twenty-stamp mill, in 1881 used one of sixty stamps in addition, crushing eighty tons of ore daily. The vein was of great size, depth, and richness. While the Alice may be taken as the representative silver mine of Butte, the Moulton, Lexington, Anaconda, and many others produced well. Eastern capital has been used to a great extent to develop these mines. The silver ores of this district carried a heavy percentage of copper, and some lodes were really copper veins carrying silver.

Cable district, twenty-five miles northwest of Butte, took it name from the Atlantic Cable gold mine, which yielded 920,000 from 100 tons of quartz, picked specimens from which weighing 200 pounds contained $7,000 in gold.

Northwest of the Cable district was the Silver district of Algonquin, on Flint Creek, where the town of Philipsburg was placed. Here were the famous Algonquin and Speckled Trout mines, with reduction-works created by the Northwest Co. In 1881 a body of ore was found in the Algonquin, which averaged 500 ounces to the ton of silver, with enough in sight to yield $2,000,000. The Hope, Comanche, and other mines in this district wore worked by a St Louis company, and produced bullion to the amount of from $300,000 to $500,000 annually since 1877. The Granite furnished rock worth seventy-five dollars per ton.

Philipsburg was laid out in 1867, its future being predicated upon the silver bearing veins in its vicinity. The first mill, erected at a great expense by the St Louis and Montana Mining Company, failed to extract the silver, which for years patient mine owners had been reducing by rude arastras and hand machinery to prove the value of their mines, and the prospects of Philipsburg were clouded. A home association, called the Imperial Silver Mining Company, was formed in 1871, which erected a five-stamp mill and roaster, and after many costly experiments, found the right method of extracting silver from the ores of the district. The stamps of their mill being of wood were soon worn out, and the company mad contracts with the St Louis company’s mill to crush the ore from the Speckled Trout mine, the machinery having to be changed from wet to dry crushing, and two new roasting-furnaces erected, the expense being borne by the Imperial Company.

The process which was adopted in this district is known as the Reese River chloridizing process. The ore, after being pulverized, dry, is mixed with 6 per cent of common salt, placed in roasting-furnaces – 1,200 pounds to each furnace – and agitated with long-handled iron hoes for 44 hours, while subjected to a gradually increasing heat. After being drawn and cooled, the pulp is amalgamated in Wheeler pans. The wet pulp, agitated in hot water and quicksilver, after four hours is drawn into large wooden vats called settiers, with revolving arms, from which it passes through a small pan, where the last of the amalgam which may have escaped is saved. It is then retorted and turned into bullion. The cost of milling and roasting the ore was $40 per ton, and the yield $125. Eight tons per day of 24 hours was the capacity of the works. Deer Lodge New Northwest, June 22, 1872. The salt used in reducing ores in Montana is chiefly brought from the Oneida salt-works of Idaho.

In 1876 the St Louis company took $20,000 worth of silver bullion from 157 tons of the Hope ore, and the average yield of medium ore was rated at $65 per ton. As a result of the profitable working of the mines of this district, the population, which in 1872 was little over 200, by 1886 had doubled. In every direction from Flint Creek, the valley of which is a rich agricultural region, the hills are full of minerals. At Philipsburg there is about four per cent of gold in the bullion. North from there the gold increases, until near Beartown it is almost pure. Between Philipsburg and the mouth of Flint Creek veins carrying silver, gold, copper, and iron abound.

In Lewis and Clarke County the quartz gold mines held their own. The Whitlatch Union after producing $3,500,000 suspended, that its owners might settle some points of difference between them, and not from any want of productiveness. About twenty-five miles northwest of Helena was the Silver Creek or Stemple district, the most famous of whose mines of gold is the Penobscot, discovered by Nathan Vestal, who took out $100,000, and then sold the mine for $400,000. The mines in this district produce by milling about ten dollars per ton on an average. The Belmont produced with a twenty-stamp mill $200,000 annually, at a profit of nearly half that amount. The Bluebird, Hickory, Gloster, and Drum Lemond were averaging from ten to twelve dollars to the ton.

Silver mines were worked at Clancy, eighteen miles south of Helena. At AVickes, twenty-five miles south, were the most extensive smelting-works in Montana, erected by the Alta-Montana Company, which had a capital stock of $5,000,000, and calculated to treat all classes of ores in which silver and lead combined. Silver was discovered on Clarke fork of the Yellowstone in 1874, and F. D. Pease went to Pa in the spring of 1875 to arrange for erecting smelting works; but Indian troubles prevented mining in that region until 1877, when the Eastern Montana Mining and Smelting Company erected furnaces. In 1873 the famous Trapper silver lode was discovered, followed immediately by others in the vicinity.

As a rule, the ores of Montana are easily worked. The rock in which auriferous and argentiferous veins occur is limestone or granite, often granite capped with slate. The presence of lead and copper simplifies the process of the reduction of silver, and in general the character of Montana galena ores does not differ greatly from those of Utah, Colorado, eastern Nevada, and Idaho. No lead mines have been worked, though they exist in these territories, but the lead obtained from their silver ores furnished, in 1875, half of that used in the United States, which was 61,473 tons. Copper lodes are abundant and large, and are found near Butte, at White Sulphur Springs, and in the Musselshell country, as well as in several other parts of the country. Iron is found in a great number of places. Deer Lodge County has an iron mountain four times larger than the iron mountain of Missouri. Fine marble, excellent building stone, fire-clay, zinc, coal, and all the materials of which and with which men build the substantial monuments of civilization, are grouped together in Montana in a remarkable manner, when it is considered that the almost universal estimate of a mineral country is that it is unfit for the attainment of the greatest degree of refinement and luxury, and that when the precious metals are exhausted, nothing worth remaining for in the country will be left.

In 1879 the United States assay office was opened at Helena, congress having enacted that the secretary of the treasury might constitute any superintendent of a mint, or assayer of an assay office, an assistant treasurer to receive gold coin and bullion on deposit. The assay office was a relief to miners, who had been forced to send their bullion east at exorbitant charges. The silver export aggregated in1879 $6,635,022. The non-mineral exports, after ten years of territorial existence, were as follows:

Buffalo robes, 6,500 @ $5 $327,500

Antelope, deer, elk, bear, wolf, and other skins @ 50 cents a lb. . . . 50,000

Beaver, otter, mink, etc 20,000

Flint hides, 400,000 lbs @ 12 cents 60,000

Sheep peltries 5,000

Wool, 100,000 lbs @ 35 cents 35,000

Cattle, fat, @ $27.50, 3,500 head 101,250

Stock-cattle @ $20, 1,000 head 20,000Total $608,750

Deer Lodge New Northwest, April 30, 1875.There was received at Omaha, in 1876, over $60,000,000; $27,000,000 in silver bullion, handled by express, besides a large amount sent as freight. The gold handled was $25,000,000. The Omaha smelting- works furnished $5,000,000. Of the silver, $10,000,000 was in coin, about half of which was returned. Of the whole, the Black Hills furnished $2,000,000; Colorado, Montana, and Idaho the rest. Omaha Republican, in Bozeman Avant-Courier, Feb. 8, 1877.

An agricultural, mechanical, and mineral association was incorporated in Dec. 1867, which held its first fair from the 6th to the 12th of Sept., 1868, at Helena. Governor Smith was the first president; Sol Merideth, vice-president; W. E. Cullen, secretary; J. T. Forbes, treasurer; J. F. Farber, W. L. Irvine, W. S. Travis, C P. Higgins, W. L. Vantilburg, J. B. Campbell, and Philip Thorn, directors. Helena Montana Post, March 17, 1868. A territorial grange was organized soon after. Missoula County held its first fair in 1876. It will be seen that, under the conditions set forth as existing previous to the opening of railroad communication, no matter what its facilities for agriculture, Montana would not establish a reputation as a farming country. Nevertheless it was gradually corning to be better understood in this respect with each succeeding year. It has been demonstrated that new soils are the most highly productive, the yield of grain, and particularly of vegetables, being often astonishingly great in the territories. Therefore I pass over the numerous instances of enormous garden productions, to the statement that as a wheat country virgin Montana was not surpassed, and all the cereals except corn yielded largely. In the higher valleys grain was likely to fail on account of frost, but in not too elevated parts the yield was from thirty to fifty bushels per acre. Wheat averaged thirty bushels and oats seventy-fire. The following table in Strahorn’s Montana, 82, is valuable, as recording the names of pioneer agriculturists, with their locations:

A. O. England, Missoula Valley

Robert. Vaughn, Sun River Valley

M. Stone, Ruby Valley

Brockway, Yellowstone Valley

Brigham Reed, Gallatin Valley

Marion Leverich, Gallatin Valley

William Reed, Prickley Pear Valley

Charles Rowe, Missouri Valley

Con. Korhs, Deer Lodge Valley

John Rowe, Gallatin Valley

Robert Barnett, Reese Creek Valley

S. Hall, Ruby ValleyThe soldiers at Fort Ellis in the Gallatin Valley raised all the vegetables to feed the five companies stationed there, thereby saving the government between $7,000 and $8,000. General Brisbin, who was for a long time in command of that post, was one of the most enthusiastic writers on the resources of the country, contributing articles to the American Agriculturist and other journals, which were copied in the Montana newspapers. See Helena Herald, Jan. 2, 1879. Rye raised by B. F. Hooper of Bowlder Valley produced grains ½ larger than the ordinary size, plump, gold-tinted, and transparent as wheat – 65 pounds to the bushel. Three quarts of seed yielded 10 bushels of grain, sown in the spring. This seed is said to have come from some grains taken from the craw of a migratory bird killed in Oregon in 1863. Virginia Montana Post, Jan. 29, 1868.

As in every country, the valleys were first settled. What the uplands, now devoted to grazing, will produce remains to be demonstrated in the future. Although it is generally thought that comparative altitude is an important factor in the making of crops, it is now pretty well understood that where bunch grass grows wheat will grow as well.

The average altitude of Montana is less by 2,260 feet than the average altitude of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico. Official reports make the mean elevation of Montana 3,900 feet; of Wyoming 6,400; of Colorado 7,000; and of New Mexico 5,300. Of Montana’s 145,780 square miles, an area of 51,000 is less than 4,000 feet above the sea; 40,700 less than 3,000. The towns are either in mining districts, which are high, or in agricultural districts, which are lower; therefore the following list of elevations is indicative of the occupations of the inhabitants:

Argenta. 6,337

Beaverhead 4,404

Bighorn City 2,831

Boetler’s Ranche 4,873

Bozeman 4,900

Butte 5,800

Bannack 5,896

Beaverstown 4,942

Blackfoot Agency 3,1 09

Bowlder 5,000

Brewer’s Springs 4,957

Camp Baker 4,538

Carroll 2,247

Deer Lodge 4,546

Fort Benton 2,780

Fort Shaw 6,000

Fish Creek Station 4,134

Fort Ellis 4,935

Gallatin City 4,838

Helena 4,266

Hamilton 4,342

Jefferson 4,776

Lovell 5,405

Montana City 4,191

Missoula 3,900

Nevada City 5,548

Sheridan 5,221

Salisbury 4,838

Virginia City 2,824

Whitehall 4,639It will be observed by a comparison with the preceding table that an altitude of nearly 5,000 feet, as at Bozeman, Fort Ellis, and Gallatin City, does not affect the production of cereals unfavorably. Sun River Valley near Fort Shaw, at a considerably greater altitude, produces 100 bushels of oats to the acre.[

]

- An earthquake was felt at Helena in the spring of 1869, which did no damage; a tornado visited the country in April 1870- both rare occurrences. In 1868, which was a dry year, Deer Lodge Lake, at the base of the Gold Creek Mountains, was full to the brim, covering 50 or 60 acres. In 1870, with a rainy spring, it had shrunk to an area of 100 by 150 feet. The lake has no visible outlet, but has a granite bottom. Deer Lake New Northwest, May 27, 1870. Thirty miles from Helena is the Bear Tooth Mountain, standing at the entrance to the Gate of the Mountains canon. Previous to 1878 it had two tusks fully 500 feet high, being great masses of rock 300 feet wide at the base and 150 feet on top. In February 1878 one of these tusks fell, sweeping through a forest, and leveling the trees for a quarter of a mile. Helena Independent, Feb. 14, 1878.[

]

- One of the largest fruit-growers in the country was D. W. Curtiss, near Helena. He came from Ohio about 1870 a poor man. In 1884 he owned his farm, and marketed from 4,000 to $7,000 worth of berries and vegetables annually.[

]

- Early Montana Farmers[

]