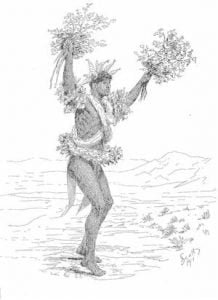

Tablita (Tablet) or Corn Dance, Pueblo of San Domingo, New Mexico, August 1870

The question of physical condition is one less dependent upon diet than the mode of life which renders general development a result, No better test of a high grade of physique could be found than the prolonged and fatiguing dances, lasting for the greater part of as day, indulged in at all of the pueblos. I have witnessed three of these great dances and several minor ones. At San Domingo, August 12, 1890, 200 dancers, male and female, participated, led by 2 choruses, each of 40 male voices. This display being regarded the finest to be seen among pueblos, with the exception of that at Zuñi, I confine my description to the dance as I saw it there, with occasional allusions to those of Santa Clara and Laguna.

The Tablita or corn dance has for its purpose supplication for rain. Most of the choruses chanted by the attendant musicians are invocations to the clouds. The tablet worn by the women upon their heads is figured with the scalloped lines of cumulus clouds, and on either side, and between them a bolt of lightning. In common with many of the old Indian rites among the Pueblos, this also has been utilized by the Catholic Church and made to serve for the support of a church ritual. Early in the day mass is said in the church and a sermon preached. The body of the congregation at these services is usually composed, of visiting Mexicans, the Indians maintaining an indifferent and fluctuating attendance. Throughout the village meanwhile active preparations are in progress for the dance. Feasting and bartering are at their height. Every door is open and food spread, and a welcome ready for any comer. The religions services being ended, unrestrained freedom is proclaimed by the irregular discharge of a dozen muzzle-loading army rifles, and immediately after the statue of the patron saint, a relic of early Spanish art, is hurried at quickstep, to the notes of a violin, from the temporary booth, which in San Domingo, serves in place of the church, to a shrine formed of green boughs and lined with blankets set up in a plaza, Here o it is deposited amid another volley from the muzzle loaders, and the assembly disperses.

In the 2 great estufas of the village most active preparations have been in progress, A descent into one of the se greenrooms was permitted me at Santa Clara. Ascending as ladder to the fiat roof of the estufa, we approached the open skylight in the center, whence issued from below a chorus of voices accompanied by a drum. With uncovered head I followed my guide down the almost perpendicular rungs of a lingo ladder, and stood upon the hard, clay floor of the Indian council chamber. The apartment is 40 feet square, unfurnished save by the adobe fireplace placed beneath the skylight and a few poles suspended from the rafters, upon which hang the garments of the dancers. In the cool tenement, thinly lighted, the athletes move to and fro, perfecting their ensemble with grave deliberation. Neither haste nor confusion is noted; conversation is indulged in sparingly and in low tones. Young lads are given assistance now and then, though this is never asked.

The naked body is first covered with a thin glaze of clay mud, rubbed smoothly over the body many, times more than is necessary to effect an evenly laid ground. This massage lubrication being indulged to the full sensuous delight of the subject he finally stands forth red, yellow, or blue, These under colors are important as designating the line which one is to occupy in the dance; the sriperdecoration is largely a matter of fancy. From the knee to the instep may be repainted another color, but the body and arms are never touched save by bands of ocher, which are here admissible. The face from the outer corner of the eyes and over the cheekbones is clashed with vermilion.

Upon the body thus decorated the details of the scanty costume are applied. Small bunches of red, blue, and yellow feathers are tied to the forelock and fanlike a bang over the eyes. The hair, glossy from its recent washing with soapweed, is freed from its queue bindings and falls at fall length. Around each biceps is bound a bracelet of woven green worsted, 3 inches wide, The waist is covered with a light, white cloth, often a flour sack, the brand rendered available as decoration. Over this, falling from the hips, hangs a narrow woven pouch supporting long strings, each ending in a small ball and reaching to the ankle. From the buttock to the ground trails the skin and tail of a silver gray fox. Below the knee a band of goathide is tied with goat and pig hoofs or tiny sleigh bells attached. The feet are moccasined, the heels fringed with wide tufts of deerhide. Necklaces of coral, turquoise, mother-of-pearl, and silver beads, and sprigs or cedar introduced in the belt and armlets complete the costume.

While the principal actors are thus being made up, the leader of the chorus, squatted upon the ground and surrounded by his 40 singers, is leading a final rehearsal. Again and again is the intonation criticized and the gestures practiced. The magic influence of deep-toned harmony makes rapid impress upon susceptible natures. In rapt gaze the coal black eyes flash with lustrous fire, nostrils dilate, the gleam of handsome rows of teeth breaks out now and then with an expression of ecstasy which captures the entire figure, heads are swaying from side to side, and lips drool in the happy frenzy which has overtaken the group. But the master, like the typical leader of music the world round, is unmoved, displeased, despotic. To the singers, led by the rapid and changeless bass drum beat, the chants they are practicing seem to possess almost electrifying power.

Now come rain! Now come rain!

Fall upon the mountain; sink into the ground.

By and by the springs are made

Deep beneath the hills.

There they hide and thence they come,

Out into the light; down into the stream.

The arms are extended above the head, the fingers are given a fluttering motion, and the hands slowly lowered. This is frequently repeated. A violent storm and slanting rain, the rush of a tornado and lightning dashes are occasionally indicated, but the gentle rain with its sweeping motion seems to be the favorite.

Another chorus is thus translated:

Look to the hills! Look to the hills!

The clouds are hanging there,

They will not come away;

But look, look again. In time they will come to us

And spread over all-the pueblo.

Another chorus, which is the main one daring the entire day, is as follows:

Look at us! Look at us!

Notice our endurance!

Watch our steps and time and grace,

Look at us! Look at us!

The women, who have been arraying themselves at their own homes, are now descending the broad ladder in groups of 2 and 3. The tablita, or headdress, worn by them is put on in the estufa. It is a light board, 9 by 14 inches, set upright and cut at the bottom to fit the head. It is painted malachite green, and notched on either side like stairs toward an apex at the top. Little posts tufted with feathers are left on either side of the acute angle thus made. The center of the tablet is cut out in the shape of a short mallet audits surface decorated with figures of clouds on either side, lightning between these, and below the serpent, which is an object of worship throughout the pueblos. The young men assist in tying on these unwieldy- appendages, for which much care is necessary to render it possible for them to be carried hi an upright position. They are similar to Moqui or Zuñi manufacture. They then select for them sprigs of pine and cedar stems, a bunch for each hand. These attentions of husbands to wives and of the young lover to the idol of his affections form one of the most charming pictures to be seen among the Pueblos. This is the day for marriages, which are performed early in the morning at the church. These Indians always receive the rite of baptism, marriage, and burial from the Catholic Church. At San Domingo 10 happy brides and grooms, all under 20 years, took part in the dance. The women mature early, are uniformly pretty, and are blessed with remarkable chest and waist development. Fatigue under physical effort is unknown to them.

I selected for my point of observation a broad, second story platform.

From the end of the main street the rapid approach of 6 figures, fantastically decked, is the announcement that the, sights of the day have begun, These figures are buffoons, or, as the translation of the Indian word signifies, grandfathers, having all the punitive privileges of the patriarchal head of a family. Freelances they are, piercing with the broad point of their practical jokes any victim from the ranks of the spectators. Even the governor is not exempt. Their mirth, however, is harmless, seldom pressed further than the incarceration of seine hapless innocent, led off amidst loud fulminations against his reputation, or the unbending of some absorbed onlooker whose super dignity renders him a target.

The disguise of these clowns renders them unrecognizable; mouths are expanded by broad lines of paint, imparting a grinning expression. Their eyes flash flames of vermilion. Straws and cornhusks are crammed promiscuously through their hair, which, being arranged a la pompadour, forms a heavy mass on the head. This, together with the whole body, is “grayed” as a sign of age by a wash of ground gypsum. Over the arms and legs bands of light purple clay, followed by the horizontal lines of the body decoration, give a zebra appearance, which adds to the grotesqueness of the figure.

A large bustle of cloths is bestuck with turkey buzzard feathers and upheld by a girdle about the waist. A tortoise shell, with a string of pig toes hanging either from the belt or about the leg, provides the wearer with an accompaniment to his never ceasing activities. The tour by these 6 clowns, singing as they move in close line through the center of each street in the village, is watched with great interest by the spectators, who walk in crowds by their side or arrange themselves thickly along the housetops, and so keep them in view until they disband. This disbanding is done like a flash, the 6 scattering in as many directions, disappearing through doors, up ladders, down skylights, to reappear behind fleeing women and screaming infants. But in contrast with such reckless confusion is the measured advance of 2 solid lines of figures slowly pouring out of the crater of the estufa like an army of ants aroused from their citadel. No shout welcomes their oncoming, though the bearer of the lofty pole, crowned with sacred eagle plumes and hung with flying regalia, lowers it now and again to the awaiting crowds. Awe and reverence are expressed in the contemplation of the scene. Crowded about their leader the chorus attends the head of the column, and when the end of the long line has cleared the estufa the drummer, covering with his eye the completed display, commences with a sudden staccato rap from his single stick a quickstep beat, which does not cease for the rest of the day. At this signal every left feet, in the procession is instantly raised and every right arm extended, to fall again as instantly. The feet are planted squarely on the ground, heel and toe striking together, and, tufted as they are with a broad fringe of deerskin, the action calls to mind the stamping of a heavy horse with shaggy fetlocks. Dry gourds, containing parched corn, are carried by the men in the right hand, so that every extended motion with that arm is accompanied by a rattle. The women follow implicitly the lead of the men, and besides this, their only occupation is to beat time in swaying motion from side to side with the sprigs of piñon. While the men elevate their feet from 6 to 8 inches, the women barely raise theirs from the ground, but proceed with a shuffling movement. This rapid treadmill exercise has continued for 5 minutes, and hardly as many feet of ground have been covered from the spot where the dance commenced, The impression of what at first was fascinating by its great precision is getting monotonous, when suddenly the drumhead is struck close to the edge, a slightly higher tone is produced, and the dancers dwell for an instant on one foot and then proceed. The relief to both spectator and participant thus introduced is of wonderful effect. It is, in fact, the salvation of the dance. The chorus is meanwhile led by a high falsetto voice in a monotone of weird incantations, Each member crowds toward the center, stamping hard as he does so, and giving tongue with all the fervor of a put of hounds in sight of the quarry. The neck veins have become whipcords, eyes are strained and protruding, and above heads stretch hands and arms tossed in loose and sweeping gestures.

At the end of 40 minutes the front of the second column of 96 dancers, led by a chorus of 40 voices, makes its slow approach from the other estufa. As the standard bearers meet the staves are lowered, and when the 2 columns are parallel the drum of the second gives the signal for its singers and dancers to commence. The first chorus thereupon stops, its columns of dancers retiring slowly to the music of the second. It returns to the shelter of its own estufa, to reappear from a side alley near the dancing ground after an interval of 40 minutes. Upon each return new figures are introduced in the dance, sonic very intricate and decorative, calling to mind parts of the Virginia reel and the lancers.

As the day wears on the throngs of spectators in the plaza are thinned by attractions outside the village. A favorite gambling game is played with stones representing horses of a corral with as many gates as players, into which the horses are taken according to the throw made with stinks serving for dice, The great event of the day, and second in importance to the dance itself; is the chicken race, A cock is buried in the sand, with his head and neck protruding. At this the horsemen ride at fall gallop from a distance of 15 yards, striving to lay hold of the agile prize as they pass, When the cock is unearthed, the whole cavalcade starts in pursuit of the hero and his screeching victim, who when caught must pass the prize to the one outriding him. Thus the race continues until miles of country have been covered, usually in a circuit and in sight of the spectators, and until nothing remains of the dismembered fowl.

It is now late in the afternoon. The sun has burned its slow course almost to the dim, blue limit of the distant hills. The dance has continued since 10:30, but the last hour was entered upon with greater courage and gusto than the first. Countless lines of perspiration, marking their way from shoulder to ankle, have effaced most of the decorations of the body. The dust arising from the trampled arena has sifted into every crevice of the adornments of the morning, but though the splendor of the ritual lids departed, none of its exacting requirements are neglected. The dancers are still oblivious of all surroundings. Backs are rigid, gestures are calm, eyes abased, and the heavy hair of men and women, blown by the ever freshening currents from the south, rises and falls to the movement of their bodies in instant time with the resolute tones of the chorus.