Of the early history of this, the principal division of the Teton, nothing is known. During the first years of the last century they were discovered by Lewis and Clark on the banks of the upper Missouri, south of the Cheyenne River, in the present Stanley County, South Dakota. They hunted and roamed over a wide region. and by the middle of the century occupied the country between the Forks of the Platte and beyond to the Black Hills. While living on the banks of the Missouri their villages undoubtedly resembled the skin-covered tipi settlements of the other kindred tribes, and later, when they had pushed farther into the prairie country, there was probably no change in the appearance of their structures. A very interesting account of the villages of this tribe, with reference to their ways of life, after they had arrived on the banks of the Platte, is to be found in the narrative of Stansbury’s expedition, during the years 1849 and 1850.

July 2, 1849, the expedition crossed the South Fork of the Platte, evidently at some point in the western part of the present Keith County, Nebraska, and on the following day “crossed the ridge between the North and South Forks of the Platte, a distance of eighteen and a-half miles.” On July 5 the expedition began moving up the right bank of the North Fork, and after advancing 23 miles encamped on the bank of the river. They had arrived in the region dominated by the Oglala. “Just above us, was a village of Sioux, consisting of ten lodges. They were accompanied by Mr. Badeau, a trader; and having been driven from the South Fork by the cholera, had fled to the emigrant-road, in the hope of obtaining medical aid from the whites. As soon as it was dark, the chief and a dozen of the braves of the village came and sat down in a semicircle around the front of my tent, and, by means of an interpreter, informed me that they would be very glad of a little coffee, sugar, or biscuit. I gave them what we could spare.” This particular band had not suffered very severely from the ailment, but were greatly heartened to receive medicines from the doctor, or “medicine-man,” of the expedition, and when they returned to their village “the sound of the drum and the song, expressive of the revival of hope, which had almost departed, resounded from the medicine lodge, and continued until a late hour of the night.” 1 During this visit some of the Indians told of a larger camp about 2 miles distant, where many were ill with the dreaded malady.

The following morning, July 6, 1849, the expedition resumed its advance up the valley, and soon reached the “upper village,” of which an interesting account is given in the journal. It “contained about two hundred and fifty souls. They were in the act of breaking up their encampment, being obliged to move farther up the river to obtain fresh grass for their animals. A more curious, animated, and novel scene I never witnessed. Squaws, papooses, dogs, puppies, mules, and ponies, all in busy motion, while the lordly, lazy men lounged about with an air of listless indifference, too proud to render the slightest aid to their faithful drudges. Before the lodge of each brave was erected a tripod of thin slender poles about ten feet in length, upon which was suspended his round white shield, with some device painted upon it, his spear, and a buckskin sack containing his ‘medicine’ bag. We continued our journey, accompanied for several miles by the people of both villages. The whole scene was unique in the highest degree. The road was strewn for miles with the most motley assemblage I ever beheld, each lodge moving off from the village as soon as its inhabitants were ready, without waiting for the others. The means of transportation were horses, mules, and dogs. Four or five lodge-poles are fastened on each side of the animal, the ends of which trail on the ground behind, like the shafts of a truck or dray. On these, behind the horse, is fastened a light framework, the outside of which consists of a strong hoop bent into an oval form, and interlaced with a sort of network of rawhide. Most of these are surmounted by a light wicker canopy, very like our covers for children’s wagons, except that it extends the whole length and is open only at one side. Over the canopy is spread a blanket, shawl, or buffalo-robe, so as to form a protection from the sun or rain. Upon this light but strong trellice-work, they place the lighter articles, such as clothing, robes, &c., and then pack away among these their puppies and papooses, (of both which they seem to have a goodly number;) the women, when tired of walking, get upon them to rest and take care of their babies. The dogs also are made to perform an important part in this shifting of quarters. Two short, light lodge-poles are fastened together at the small end, and made to rest at the angle upon the animal’s back, the other end of course, trailing upon the ground. Over his shoulders is placed a sort of pad, or small saddle the girth of which fastens the poles to his sides, and connects with a little collar or breast-strap. Behind the dog, a small platform or frame is fastened to the poles, similar to that used for the horses, upon which are placed lighter articles, generally puppies, which are considered quite valuable, being raised for beasts of burden as well as for food and the chase. The whole duty of taking down and putting up the lodges, packing up, loading the horses, arranging the lodge-poles, and leading or driving the animals, devolves upon the squaws, while the men stalk along at their leisure; even the boys of larger growth deeming it beneath their dignity to lighten the toils of their own mothers.” 2

From the preceding account of the movement of a village of the Oglala it is quite apparent they did not advance in the orderly manner followed by the Pawnee, as described by Murray in 1835, but the dreaded illness from which many were then suffering may have caused the rather demoralized condition of the band. The travois as used at that time was similar to the example shown in plate 14, although the latter was in use by the Cheyenne a generation later. But the frame was not always utilized, and often the tipi, folded and rolled, with other possessions of the family, rested upon the poles or upon the back of the horse.

Horses thus laden, and with trailing poles on either side, left a very distinctive trail as they crossed the prairie, and as described: “The trail of the Plain Indians consists usually of three paths, close together, yet at fixed distances apart. They are produced as follows: The framework of their lodges or tents are made of long poles which, on a journey, are tied to each side of a pony, and allowed to trail upon the ground. The result is that a long string of ponies, thus laden and following each other, will wear a triple path-the central one being caused by the tread of the ponies, the two outer by the trailing of the lodge-poles.” 3 An illustration of a horse so loaded is given on page 26 and is here reproduced as figure 3. It bears the legend “Sioux Indian Lodges or Tents; one packed for a journey, the other standing,” and, although crude, conveys a clear conception of the subject.

To continue t

he narrative of the Stansbury expedition. The party advanced up the river and pursued their journey to the Great Salt Lake and there wintered. The following year they returned to the east and on September 21, 1850, reached the left bank of the North Fork of the Platte, at a point near the center of the present Carbon County, Wyoming. Describing the site of their encampment that night, near the bank of the Platte: “The place we now occupy has long been a favorite camp-ground for the numerous war-parties which annually meet in this region to hunt buffalo and one another. Remains of old Indian stockades are met with scattered about among the thickets; and the guide informed us, that four years since there were at one and the same time, upon this one bottom, fifteen or twenty of these forts, constructed by different tribes. Most of them have-since been destroyed by fire. As this was the season of the year when we might expect to find them upon their expeditions, we were on the qua vine, lest we should be surprised.” They remained in camp the following day, Sunday, and that evening entered in the journal: “Several herds of buffalo were seen during the day.”

The morning of the 23d was warm and cloudy, and the party soon after leaving their camp forded the river “on a ripple, with a depth of eighteen inches.” The water was clear, with a pebbly bottom. That this location was frequented by Indians was again indicated by the discovery of another great group of “forts,” as told in the narrative: ” Immediately above where we crossed, were about twenty Indian forts, or lodges constructed of logs set up endwise, somewhat in the form of an ordinary skin lodge, which had been erected among the timber by different war-parties: they appeared to be very strong, and were ball-proof.” 4 These strongly constructed lodges will at once recall the rather similar structures which stood at some of the Siouan villages, on the Mississippi below the mouth of the Minnesota, during the early years of the last century.

On September 27, when about midway across the present Albany County, Wyoming, the expedition encountered a large number of Indians belonging to a village a short distance beyond. These proved to be the Oglala. and during the following day the village was visited by Stansbury, who wrote in the journal: “This village was the largest and by far the best-looking of any I had ever seen. It consisted of nearly one hundred lodges, most of which were entirely new, pitched upon the level prairie which borders on the verdant banks of the Laramie. No regular order seemed to be observed in their position, but each builder appeared to have selected the site for his habitation according to his own fancy.

“We rode at once to the lodge of the chief, which was painted in broad horizontal stripes of alternate black and white, and, on the side opposite to the entrance, was ornamented with large black crosses on a white ground. We found the old fellow sitting on the floor of his lodge, and his squaw busily engaged over a few coals, endeavoring to fry, or rather boil, in a pan nearly filled with grease, some very suspicious-looking lumps of dough, made doubtless from the flour they had received from us yesterday. After some further conversation. another chief, named the ‘Iron Heart,’ rose up and invited us to a feast, at his lodge: we accordingly accompanied him, and found him occupying the largest and most complete structure in the village, although I was assured that the Sioux frequently make them much larger. It was intended to be used whenever required, for the accommodation of any casual trader that might come among them for the purpose of traffic, and was accordingly called ‘The Trader’s Lodge.’ It was made of twenty-six buffalo-hides, perfectly new, and white as snow, which, being sewed together without a wrinkle, were stretched over twenty-four new poles, and formed a conical tent of thirty feet diameter upon the ground, and thirty-five feet in height.” This must have been a magnificent example of the tipi of the plains tribes, and is one of the largest of which any record has been preserved.

Moving in a southeastward direction from the great village, they passed many mounted Indians killing buffalo, and later in the day passed another Oglala village of some 50 lodges, moving southward. The surface of the prairie for many miles was strewn with the remains of buffalo, which had been killed by the Indians and from which only choice pieces had been removed. 5 They were now ascending the western slopes of the Black Hills, and approaching the region dominated by the Cheyenne, and two days later, September 29, 1850, were a short distance south of a village of the latter tribe.

The region just mentioned, the southeastern part of Wyoming, was traversed by a missionary who, July 24, 1835, encountered a party of 30 or 40 mounted Indians. “They were Ogallallahs, headed by eight of their chiefs, clad in their war habiliments, and presenting somewhat of a terrific appearance. They told us their whole village was only a few hours travel ahead of us, going to the Black Hills for the purpose of trading.” Late the following day the party overtook the Indians, “consisting of more than two thousand persons. These villages are not stationary, but move from place to place, as inclination or convenience may dictate. Their lodges are comfortable, and easily transported. They are constructed of eight or ten poles about eighteen feet long, set up in a circular form, the small ends fastened together, making an apex, and the large ends are spread out so as to enclose an area of about twenty feet in diameter. The whole is covered with their coarse skins, which are elk, or buffalo taken when they are not good for robes. A fire is made in the centre, a hole being left in the top of the lodge for the smoke to pass out. All that they have for household furniture, clothing, and skins for beds, is deposited around according to their ideas of propriety and convenience. Generally not more than one family occupies a lodge.” 6

Fort Laramie was reached by the Stansbury expedition on July 12, 1849, after advancing about 100 miles beyond the Oglala villages passed six days before. The fort stood on the emigrant road, and was likewise a great gathering place of the neighboring Indians. An interesting account of the visit of a party of emigrants just four years before is preserved: “Our camp is stationary to-day; part of the emigrants are shoeing their” horses and oxen; others are trading at the fort and with the Indians. In the afternoon we gave the Indians a feast, and held a long talk with them. Each family, as they could best spare it, contributed a portion of bread, meat, coffee or sugar, which being cooked, a table was set by spreading buffalo skins upon the ground, and arranging the provisions upon them. Around this attractive board, the Indian chiefs and their principal men seated themselves, occupying one fourth of the circle; the remainder of the male Indians made out the semi-circle; the rest of the circle was completed by the whites. The squaws and younger Indian formed an outer semi-circular row immediately behind their dusky lords and fathers.” 7 This was June 25, 1845. and the account of the gathering of emigrants and Indians is followed by a brief description of the fort itself which is of equal interest: ” Here are two forts. Fort Laramie, situated upon the west side of Laramie’s fork, two miles from Platte river, belongs to the North American Fur Company. The fort is built of adobes. The walls are about two feet thick, and twelve or fourteen feet high, the tops being picketed or spiked. Posts are planted in these walls, and support the timber for the roof. They are then covered with mud. In the centre is an open square, perhaps twenty-five yards each way, along the sides of which are ranged the dwellings, store rooms, smith shop, carpenter’s shop, offices. &c., all fronting upon the inner area. There are two principal entrances; one at the north, the other at the south.” 8

Outside the fort proper, on the eastern side, stood the stables, and a short distance away was a field of about 4 acres where corn was planted. “by way of experiment.” About 1 mile distant was a similar though smaller structure called Fort John. It was then owned and occupied by a company from St. Louis, but a few months later it was purchased by the North American Fur Company and destroyed. Such were the typical “forts,” on and beyond the frontier during the past century. The Indians would gather about the fort, their skin tipis standing in clusters over the surrounding prairie. Such groups are shown in plate 24a, b. These two very interesting photographs were made during the visit of the Indian Peace Commission to Fort Laramie in 1868, and it is highly probable the tipis shown in the pictures were occupied by some of the Indians with whom the commissioners treated.

The Black Hills lay north and west of the region then occupied by the Oglala, and although it is known that the broken country was often visited and frequented by parties of Indians in quest of poles for their tipis, yet it seems doubtful if any permanent settlements ever stood within the region. Dodge, in discussing this question, said: “My opinion is, that the Black Hills have never been a permanent home for any Indians. Even now small parties go a little way into the Hills to cut spruce lodge-poles, but all the signs indicate that these are mere sojourns of the most temporary character.

“The ‘teepe, or lodge, may be regarded as the Indian’s house, the wickup as his tent. One is his permanent residence, the other the make-shift shelter for a night. Except in one single spot, near the head of Castle Creek, I saw nowhere any evidence whatever of a lodge having been set up, while old wickups were not unfrequent in the edge of the Hills. There is not one single teepe or lodge-pole trail, from side to side of the Hills, in any direction, and these poles, when dragged in the usual way by ponies, soon make a trail as difficult to obliterate as a wagon road, visible for many years, even though not used.” 9

Col. R. I. Dodge, from whose work the preceding quotation has been made, was in command of the military escort which formed part of the expedition into the Black Hills during the summer of 1875. The traces of the lodges which had stood near the head of Castle Creek. as mentioned in 1875, undoubtedly marked the position of the small encampment encountered by the Ludlow party the previous year. In the journal of that expedition, dated July 26, 1874, is to be found this brief mention: “In the afternoon occurred the first encounter with Indians. A village of seven lodges, containing twenty-seven souls, was found in the valley. The men were away peacefully engaged in hunting; the squaws in camp drying meat, cooking, and other camp avocations. Red Cloud’s daughter was the wife of the head-man, whose name was One Stab. General Custer was desirous they should remain and introduce us to the hills, but the presence among our scouts of a party of Rees, with whom the Sioux wage constant war, rendered them very uneasy and toward nightfall, abandoning their camp, they made the escape. Old One Stab was at headquarters when the flight was discovered, and retained both as guide and hostage. The high limestone ridges surrounding the camp had weathered into castellated forms of considerable grandeur and beauty and suggested the name of Castle Valley.” 10 Red Cloud, whose daughter is mentioned above, was one of the greatest chiefs and warriors of the Oglala; born in 1822 near the forks of the Platte, and lived until December, 1909.

Although there may never have been any large permanent camps within the Black Hills district, nevertheless it is quite evident the region was frequented and traversed by bands of Indians, who left well-defined trails. Such were discovered by an expedition in 1875 and after referring to small trees which had been bent down by the weight of snow the narrative continued: “The snow must be sometimes deep enough to hide trails and landmarks, as the main Indian trails leading through the Hills were marked by stones placed in the forks of the trees or by one or more sets of blazes, the oldest almost overgrown by the bark.” 11 And in the same work 12 , when treating of the timber of the Hills, it was said: “The small slender spruce-trees are much sought after by the Indians, who visit the Hills in the spring for the purpose of procuring them for lodge-poles.”

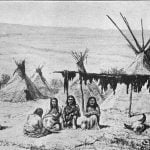

In another work Dodge described the customs of the tribes with whom he had been in close contact for many years. The book is illustrated with engravings made from original drawings by the French artist Griset, and one sketch shows a few Indians, several tipis, and frames from which are hanging quantities of buffalo meat in the process of being dried. 13 This suggests the scene at Red Cloud’s camp. The original drawing is now reproduced as plate 1, the frontispiece.

Citations:

- Stansbury, Howard, An Expedition to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah. Philadelphia, 1855, pp. 41 45.[

]

- Stansbury, Howard, An Expedition to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah. Philadelphia, 1855, pp. 45-47.[

]

- Bell, William A., New Tracks in North America. London, 1870, pp. 25-26.[

]

- Stansbury, Howard, An Expedition to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah. Philadelphia, 1855, pp. 243-246.[

]

- Stansbury, Howard, An Expedition to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah. Philadelphia, 1855, pp. 254-257.[

]

- Parker, Samuel, Journal of an Exploring Tour Beyond the Rocky Mountains . .. in the years 1835, 36, and 37. Ithaca, N.Y., 1842, pp. 66-67.[

]

- Palmer, Joel, Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains to the Mouth of the Columbia River … 1845 and 1846. Cincinnati, 1847, pp. 25-26.[

]

- Palmer, Joel, Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains to the Mouth of the Columbia River … 1845 and 1846. Cincinnati, 1847, pp. 27-28.[

]

- Dodge, Richard Irving, The Black Hills. New York, 1876, pp. 136-137.[

]

- (Ludlow, William, Report of a Reconnaissance of the Black Hills of Dakota, made in the Summer of 1874. Washington, 1875, p. 13.[

]

- Newton, Henry and Jenney, Walter P., Report on the Geology and Resources of the Black Hills of Dakota. Washington, 1880, p. 302.[

]

- Newton, Henry and Jenney, Walter P., Report on the Geology and Resources of the Black Hills of Dakota. Washington, 1880, p. 323[

]

- Dodge, Richard Irving, The Plains of the Great West. New York, 1877, p. 353.[

]