The arrival of an express at Nashville, with letters from Mr. George S. Gaines to General Jackson and the governor, conveying the distressing intelligence of the massacre at Fort Mims, and imploring their assistance, created great excitement, and the Tennesseans volunteered their services to avenge the outrage. General Jackson, at the head of a large force, passed through Huntsville, crossed the Tennessee at Ditto’s Landing, and joined Colonel Coffee, who had been dispatched in advance, and who had encamped opposite the upper end of an island on the south side of the river, three miles above the landing. Remaining here a short time, the army advanced higher up, to Thompson’s Creek, to meet supplies, which had been ordered down from East Tennessee. In the meantime, Colonel Coffee marched, with six hundred horse, to Black Warrior’s town, upon the river of that name, a hundred miles distant, which he destroyed by fire, having found it abandoned. Collecting about three hundred bushels of corn, he rejoined the main army at Thompson’s Creek, without having seen an Indian. Establishing a defensive depot at this place, called Fort Deposite, Jackson, with great difficulty, cut his way over the mountains to Wills’ Creek, where, being out of bread, he encamped several days, to allow his foraging parties to collect provisions. The contractors had entirely failed to meet their engagements, and his army had for some days been in a perishing condition.

Jackson dispatched Colonel Dyer, with two hundred cavalry, to attack the village of Littefutchee, situated at the head of Canoe Creek, twenty miles distant. They arrived there at four o’clock in the morning, burned down the town, and returned with twenty-nine prisoners, consisting of men, women and children. Another detachment, sent out to bring in beeves and corn, returned with two Negroes and four Indians, of the war party. These prisoners, together with two others brought in by Old Chinnobe and his son, were sent to Huntsville.

The Creeks having assembled at the town of Tallasehatche, thirteen miles from the camp, the commander-in-chief dispatched Coffee, now promoted to the rank of brigadier-general, with one thousand men, with one-half of whom he was directed to attack the enemy, and with the other half to scour the country near the Ten Islands, for the purpose of covering his operations. Richard Brown, with a company of Creeks and Cherokees, wearing on their heads distinguishing badges of white feathers and deer’s tails, accompanied the expedition. Fording the Coosa at the Fish Dam, four miles above the islands, Coffee advanced to Tallasehatche, surrounded it at the rising of the sun, and was fiercely met by the savages with whoops and the sounding of drums–the prophets being in advance. Attacking the decoy companies they were soon surrounded by the troops, who charged them with great slaughter. After a short but terrible action, eighty-four women and children were made prisoners, while the bodies of one hundred and eighty-six warriors were counted upon the field, where unavoidably some women also perished. Many other bodies lay concealed in the weeds. Five Americans were killed and eighteen wounded. Late in the evening of the same day Coffee re-crossed the Coosa and reached headquarters. Not a solitary warrior begged for his life, and it is believed none escaped to the woods. These prisoners were also sent to Huntsville. General Jackson, now forcing his way over the Coosa Mountain, arrived at the Ten Islands, where he began to erect a second depot for supplies, which was protected by strong picketing and blockhouses, and which received the name of Fort Strother.

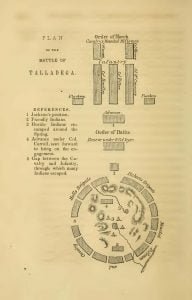

In Lashley’s fort in the Talladega town many friendly Creeks had taken refuge. The war party, in strong force, had surrounded them so effectually that not a solitary warrior could escape from the fort unseen to convey to the American camp intelligence of their critical condition. One night a prominent Indian, who belonged to the Hickory Ground town, resolved to escape to the lines of Jackson by Indian stratagem. He threw over him the skin of a large hog, with the head and legs attached, and placing himself in a stooping position, went out of the fort and crawled about before the camps of the hostiles, grunting and apparently rooting, until he slowly got beyond the reach of their arrows. Then, discarding his swinish mantle, he fled with the speed of lightning to Jackson, who resolved immediately to relieve these people. The commander-in-chief, leaving a small guard to protect his camp and sick, put his troops in motion at the hour of midnight, and forded the Coosa, here six hundred yards wide, with a rocky, uneven bottom. Each horseman carried behind him a footman until the whole army was over. Late that evening he encamped within six miles of Talladega. At four o’clock next morning Jackson surrounded the enemy, making a wide circuit, with twelve hundred infantry and eight hundred cavalry. The hostiles to the number of one thousand and eighty, were concealed in a thick shrubbery that covered the margin of a small rivulet, and at eight o’clock they received a heavy fire from the advance guard under Colonel Carroll. Screaming and yelling most horribly, the enemy rushed forth in the direction of General Roberts’ brigade, a few companies of which gave way at the first fire. Jackson directed Colonel Bradley to fill the chasm with his regiment, which had not advanced in a line with the others; but that officer failing to obey the order, Colonel Dyer’s reserve dismounted, and met the approaching enemy with great firmness. The retreating militia, mortified at seeing their places so promptly filled recovered their former position, and displayed much bravery. The action now became general along the whole line, while the Indians, who had at first fought courageously, were now seen flying in all directions. But owing to the halt of Bradley’s regiment, and the cavalry under Alcorn having taken too wide a circuit, many escaped to the mountains. A general charge was made, and the wood for miles was covered with dead savages. Their loss was very great, and could not be ascertained. However, two hundred and ninety-nine bodies were counted on the main field. Fifteen Americans were killed and eighty-five wounded. The latter were conveyed to Fort Strother in litters made of raw hides. The fort contained one hundred and sixty friendly warriors, with their wives and children, who were all to have been butchered the very morning that Jackson attacked their assailants. Never was a party of poor devils more rejoiced at being relieved. General Pillow, of the infantry; Colonel Lauderdale, of the cavalry; Major Boyd, of the mounted riflemen; and Lieutenant Barton were wounded-the last named mortally. Colonel Bradley was arrested for disobedience of orders, but was released without a trial. Jackson buried his dead and marched back to Fort Strother as rapidly as possible, for he was out of provisions. Arriving there, he was mortified to find none at that point for him. 1

About the time that the Middle and West Tennessee volunteers flocked to the standard of Jackson, a large body of volunteers from East Tennessee rendezvoused to march to the seat of war under Major-General John Cocke. Shortly afterwards General White, commanding a detachment of one thousand men, belonging to Cocke’s force, advanced to Turkey Town. From this place he reported to Jackson that he would, the next day, march in the direction of headquarters and should in the meantime, be glad to receive his orders. The latter ordered him to march to Fort Strother, and protect that place during his absence to Talladega, where, he informed him, he intended immediately to march to the relief of the garrison of Lashley’s fort. While White was on the march to Fort Strother to comply with this requisition, he received a dispatch from General Cocke ordering him to alter his route, and form a junction with him at the mouth of the Chattooga. This order he obeyed, preferring to comply with the commands of Cocke rather than those of Jackson, although the latter was generally considered the commander-in-chief of all the troops from Tennessee. Jackson was shocked at receiving an account of the retrograde march of White, and that, too, at a late hour of night, previous to the battle of Talladega; and it determined him to attack the Indians forthwith, and rush back to Fort Strother, now left with a very feeble protection.

However, before General White had reached Turkey Town, his advance-guard, consisting of four hundred Cherokees and a few whites under Colonel Gideon Morgan and John Lowrey, advanced upon the town of Tallasehatche on the evening of the 3d November, and found that it had that morning been destroyed by Coffee. Collecting twenty of the wounded Indians, they returned with them to Turkey Town.

The mischief’s of a want of concert between the East and West Tennessee troops, growing out of a jealousy of the former and a strong desire to share some of the glory which the latter had already acquired in the few battles they had fought–were in a very few days made quite apparent. Through Robert Graison, an aged Scotchman, the Hillabees (a portion of whom fought Jackson at Talladega) made offers of peace, to which the general immediately and willingly acceded. At that very time, and when Graison had hastened back with the favorable reply of Jackson, General White surrounded the Hillabee town early in the morning and effected a complete surprise, killing sixty warriors and taking two hundred and fifty prisoners. The Hillabees, it is asserted, made not the slightest resistance. At all events, not a drop of Tennessee blood was spilt. The other Hillabee towns, viewing this as flagrant treachery on the part of Jackson, became the most relentless enemies of the Americans, and afterwards fought them with fiendish desperation. The destruction of this town was in pursuance of the orders of General Cocke. White, in marching down, had already destroyed Little Ocfuske and Genalga, both of which had been abandoned by the inhabitants, with the exception of five warriors, who were captured at the former.

General Cocke, having given up the ambition of achieving separate victories, was now prepared to co-operate with Jackson, and for that purpose joined him at Fort Strother with fourteen hundred men. He was sent by the commander-in-chief back to East Tennessee with a portion of his command, whose term of service had nearly expired, with orders to raise fifteen hundred men and rejoin him in the Creek nation.

Georgia, no less patriotic than Tennessee, soon came to the relief of her brethren of the Mississippi Territory. Brigadier General John Floyd crossed the Ockmulgee, Flint and Chattahoochie, and advanced near the Tallapoosa with an army of nine hundred and fifty militia and four hundred friendly Indians, piloted by Abram Mordecai, the Jew trader of whom we have so often had occasion to speak. Before sunrise, on a cold frosty morning, Floyd attacked the Creeks, who were assembled in great force at the town of Auttose, which was situated on the east bank of the Tallapoosa, at the mouth of the Calebee Creek. Booth’s battalion, which composed the right column, marched from the center; Watson’s composed the left, and marched from its right. Upon the flanks were the rifle companies of Adams and Merriweather, the latter commanded by Lieutenant Hendon. The artillery, under Captain Thomas, advanced in the road in front of the right column. General Floyd intended to surround the town by throwing the right wing on Calebee Creek, at the mouth of which he was informed the town stood, and resting the left on the river bank below it; but the dawn of day exhibited, to his surprise, a second town, about five hundreds yards below. It was now necessary to change the plan of attack, by advancing three companies of infantry to the lower town, accompanied by Merriweather’s rifles, and two troops of light dragoons commanded by Captains Irwin and Steele. The remainder of the army marched upon the upper town, and soon the battle became general. The Indians at first advanced, and fought with great resolution, but the fire from the artillery, with the charge of the bayonets, drove them into the out-houses and thickets, in rear of the town. Many concealed themselves in caves cut in the bluff of the river, here thickly covered with cane. The admirable plans of General Floyd for the extermination of the foe were not properly executed, owing to the failure of the friendly Indians to cross the Tallapoosa to the west side, and there cut off all retreat. The difficulty of the ford and the coolness of the morning deterred them, as they stated; but fear, in all probability, was the prime cause. They now irregularly fell back to the rear of the army. However, the Cowetas, under McIntosh, and the Tookabatchas, under the Mad Dragon’s Son, fell into the ranks, and fought with great bravery. The hour of nine o’clock witnessed the abandonment of the ground by the enemy, and the conflagration of the houses. From the number of bodies scattered over the field, together with those burnt in the houses and slain on the bluff, it is believed that two hundred must have perished, among whom were the Kings of Tallase and Auttose. The number of buildings burned, some of which were of fine Indian architecture and filled with valuable articles, amounted to about four hundred.

The Americans had eleven men killed and fifty-four wounded. The friendly Indians had several killed and wounded. Important services were rendered by Adjutant-General Newman, the aids Majors Crawford and Pace, and the surgeons Williamson and Clopton. Major Freeman, at the head of Irwin’s cavalry and part of Steele’s, made bold charges upon the Indians, completely routing them. The companies led on by Captains Thomas, Adams, Barton, Myrick, Little, King, Broadnax, Cleveland, Cunningham, Lee and Lieutenant Hendon, fought with gallantry. Brigadier-General Shackleford performed efficient services in successfully bringing the troops into action, and Adjutants Montgomery and Broadnax exhibited activity and courage. The battalion of Major Booth was properly brought into action, and that of Major Watson fought with commendable spirit. The cavalry under Irwin, Patterson and Steele, charged with success when opportunities were afforded. Great heroism was displayed by Quartermaster Terrill, who, though badly wounded, escaped after his horse was shot under him. The horse of Lieutenant Strong was shot under him, and he made a narrow escape. In seven days the troops had marched one hundred and twenty miles, and fought this battle. Being now sixty miles from the depot of provisions, and the rations of the troops being nearly exhausted, Floyd, after the dead had been interred and the wounded properly attended, began the retrograde march to Fort Mitchell, upon the Chattahoochie. On ascending Heydon’s Hill, a mile east of the battleground, many of the Creeks rallied and fiercely attacked his rear, but after a few rounds they were dispersed. 2

Citations:

- A portion of the Talladega battlefield is now (1851) embraced within the limits of the beautiful and flourishing American town of that name, which contains a population of near two thousand, and is situated in a delightful valley, with magnificent mountain scenery in view.[↩]

- Upon the campaigns of the Tennesseans, under Jackson and Cocke, and the Georgians, under Floyd, I have consulted the various works and public documents upon the late war, such as the lives of Jackson by Kendall, Cobbett, Eaton and Waldo; Russell’s “History of the War,” Breckenridge’s History of the Late War, and the various American State Papers.[↩]