Extinction by Reclassification: The MOWA Choctaws of South Alabama and Their Struggle for Federal Recognition

JACQUELINE ANDERSON MATTE

Originally appearing in The Alabama Review, Volume 59, July 2006, pages 163-204. The Alabama Historical Association, founded in 1947, is the oldest statewide historical society in Alabama. The Association sponsors The Alabama Review, two newsletters each year, a state historical marker program, and several Alabama history awards. Our thanks to Jackie Matte and the Alabama Review for allowing us to present her work on Native American Genealogy.

In the 1930s, Carl Carmer, a professor at the University of Alabama and author of Stars Fell on Alabama, traveled around Alabama collecting unusual stories. He said that he chose “to write of Alabama not as a state which is part of a nation, but as a strange country in which I once lived.” 1 One of his stories describes his efforts to determine the ancestry of the so-called Cajuns who lived around Citronelle in southwest Alabama. After encountering the “Cajuns” on a visit to the area, Carmer asked his host about their heritage:

“What’s your theory of the origin of these people?”

“I can tell you as good a one as the next man. Which one do you want to hear?”

“Doesn’t anybody know?”

“Try asking around, just for fun.”

So, for two days, I asked around.

“Long time ago wasn’t no folks on them sand flats. . . .

Them Cajans sprung up right out’n the ground. Some

say they come from animals-coons and foxes and

suchlike-but that ain’t right. Just sprung up out’n the ground.” 2

Jacqueline Anderson Matte is a retired teacher and holds master’s degrees in history and education from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a B.S. from Samford University. She lives in Birmingham. This presidential address was read at the annual meeting of the Alabama Historical Association in Fairhope, April 22, 2006.

Carmer’s story provoked a flurry of interest in the “Cajans,” when in reality they were not Cajun at all. Instead, they were descendants of the indigenous Choctaw Indians of southwest Alabama. Cajun is a nickname given to Acadians, French-speaking immigrants and deportees from Acadia, Canada, who live in Louisiana. Nonetheless, Carmer’s exotic description was an early example of a deluge of articles, papers, theses, and dissertations on southwest Alabama’s so-called Cajuns that appeared between 1930 and 1972. Many of these writings were on the theme of “tri-racial isolates,” an outdated anthropological term used to describe interracial populations that existed outside mainstream society. 3 Anthropologists now consider such a designation unscientific and invalid, although some genealogists are still using it. 4

These accounts are all similar, told so often that their repetitiveness seems to imply validity. Each author has, however, simply echoed the conclusions of previous writers. “No one knows where those people came from,” is a recurrent observation. Rather than conduct historical research to clarify the situation, these authors embellished scanty and questionable data with speculation. Although the southwest Alabama Choctaws consider the term Cajun to be pejorative, it stuck. The name served as a convenient means of distinguishing the group from the surrounding black and white populations. Moreover, once the term was incorporated into the literature, it persisted; a 1948 Smithsonian Institution report, for example, included a description of the “Cajun” Indians of southwest Alabama. 5 Unfortunately, such erroneous descriptions of their identity have been the rule rather than the exception, obscuring the true identity of the Alabama Choctaws.

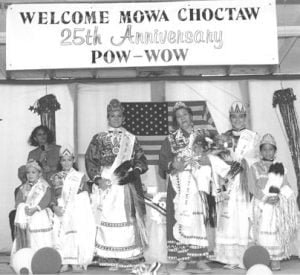

My association with the Choctaw Indians of south Alabama began in 1980 while I was researching and writing the first comprehensive history of Washington County. 6 The previous year they had adopted the designation “MOWA Choctaws,” with the acronym MOWA selected to represent their modern geographic location, an area straddling the county line between Mobile and Washington counties. I contacted their chief because I wanted to include all segments of the county’s population in my book. Evidently, this was the first time they had been asked to tell their own story, because after the Washington County history was published, the tribal chief asked me to help research their history for their petition to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) seeking federal recognition as an Indian tribe.

Federal regulations developed in 1978 outline a procedure for non-recognized Indian tribes to petition the BIA for formal recognition. These regulations require petitioning groups to demonstrate that their members comprise a “community” with internal cohesion, external boundaries, and a distinct Indian identity. To meet the criterion of a distinct Indian identity, the BIA requires petitioners to show an unbroken genealogical paper trail that connects tribal members living today to earlier generations. 7 For the MOWA Choctaws, satisfying this requirement is extremely difficult for at least three reasons. First, the traditional naming practices of Choctaws do not conform to the European pattern of using family names from generation to generation. And even after they began adopting European given names and surnames, the Chotaws did not follow a pattern that would facilitate documentary verification of lineage. In 1916, for example, federal Indian supervisor John T. Reeves reported that the Choctaws “have a peculiar system of nomenclature, usually consisting of a reversal of the Christian and surnames. For instance, the eldest son of Jim Willis is apt to be known as Willis Jim.” This is even further complicated by the occasional practice of naming “a son . . . in toto after some white man. Thus, the second son of John Anderson is liable to be called ‘Joe Welch’ not Joe Welch Anderson, but just plain Joe Welch. Where several generations have transpired it is almost impossible to determine whether a given Indian’s name is Bill William or William Bill.” 8

Second, the U.S. government’s historical documentation of these non-literate people does not record names and race consistently. Government agents in the nineteenth century recorded Indian names phonetically, with no English counterpart, when taking censuses. Consequently, it is virtually impossible to connect individuals recorded in the first Choctaw census, conducted in 1830, with those who were recorded in the census taken twenty-five years later. 9

In the 1855-56 census, Indian agent Douglas H. Cooper recorded the names of the Six Towns Choctaw Indians living in Mobile using only a phonetic spelling of their Choctaw names with no English translation. 10 Without an English name recorded next to a Choctaw name, identification of an individual is elusive if not impossible. Two additional examples of this problem appear in the records of a federal lawsuit involving MOWA ancestors. The Choctaw chief Chish-a-homa was also identified as “Captain Red Post Oak” (his last name evolved into Postoak), and the chief Eli-Tub-bee was identified as “Tom Gibson.” 11 Later, U.S. census takers assigned them the last names of the landowners on whose land they squatted and recorded them as “Free person of color,” “Mulatto,” “Mixed-blood,” or “Colored.” 12 Renée Ann Cramer, a scholar and authority on the politics of tribal acknowledgement, concludes that governmental authorities routinely imposed inappropriate racial classifications on Native Americans: “It is clear that ‘Mulatto’ was used for Indians, even those with no African ancestry; and, in Alabama, since the mid-1800s, ‘Colored’ had been used for similar persons.” 13

The third factor that makes it difficult for the MOWA Choctaws to convince BIA officials that they possess a distinct Indian identity is the reluctance of federal officials to accept oral transmission of family lineage in lieu of documentary evidence. Despite the inconsistencies of Choctaw naming practices and the vagaries of governmental census records, tribal members can nevertheless trace in detail their lineage using knowledge passed orally from generation to generation. 14

As a result of these three factors, it is almost impossible for the MOWA Choctaws-and many other non-recognized tribes as well-to authenticate their Indian racial identity using BIA guidelines. The late Native American rights advocate, Vine Deloria Jr., a Standing Rock Sioux and professor emeritus at the University of Colorado at Boulder, concurs. In his foreword to the 2002 edition of my book They Say the Wind is Red: The Alabama Choctaw Lost in Their Own Land, Deloria declared that “the federal acknowledgement process is confused, unfair, and riddled with inconsistencies. Much of the confusion is due to the insistence that Indian communities meet criteria which, if it had been applied in the past, would have disqualified the vast majority of presently recognized Indian groups.” 15

Nevertheless, unrecognized tribes commit considerable energy and resources in attempts to meet the government’s high threshold. Federal recognition, if granted, enhances a tribe’s potential for federal assistance in health care, housing, education, and business development. There is also the less tangible, but nonetheless compelling, desire by non-recognized groups to establish formal legitimacy for their claims of Indian identity. For the MOWA Choctaws, the latter is of utmost importance because of the discrimination they have endured from white southerners consumed by racism. While some people may believe racism is on the wane in America, it is clear that substantial anti-Indian sentiment persists. 16 When members of the Alabama House of Representatives were considering 1997 legislation authorizing the MOWA Choctaws to hire police officers, some representatives used the occasion to make jokes about “bows and arrows and war paint.” One legislator asked how the Choctaw officers would enforce laws: “How will that be done? Bow and arrow? Spear?” The comments prompted a warning from the speaker that representatives should apologize and refrain from further derogatory comments. 17 Chief Wilford “Longhair” Taylor of the MOWA Choctaws, a member of the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission, responded by explaining to the local press that “rather than using bows and arrows and war paint, we now use computer chips and attaché cases.” 18

Research to document MOWA eligibility for federal recognition began in 1983 with interviews of community elders. Well-respected members of the tribe volunteered to identify elders “who knew a lot” and to act as liaisons. “Go-betweens” were necessary to facilitate contact between the elders and me-and eventually other researchers-because of the elders’ distrust of “outsiders.” On several occasions, I was asked to wait in the car while the tribal liaison went into the house to “limber them up.” Once the purpose of our visit was explained and the tribal liaison vouched for me, the elders agreed to talk. Word spread throughout the Indian community, and the elders increasingly welcomed us into their homes. With tape recorder and camera, we traveled the back roads from house to house, eventually compiling two hundred hours of interviews. We encountered muddy ruts and sandbeds, and our vehicle got stuck more than once. Neighbors and volunteers came to our rescue and got us moving again every time. Information from the interviews provided clues of where to search for documentation. This search took us to well-kept cemeteries and overgrown, abandoned graveyards to record the births and deaths of MOWA ancestors. We encountered dust, dirt, and mildew in the basements of various county courthouses, where we searched through property-tax records, estate papers, deed books, and court cases. Tribal volunteers and I searched libraries and archives in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Washington, D.C. In 1987, we submitted a two-hundred-page petition, which included copies of the records found in these depositories. 19 Nevertheless, in 2006, after almost three-quarters of a century, Carmer’s question—“What’s . . . the origin of these people”— continues to be an issue in the MOWA Choctaws’ quest for federal recognition.

The MOWA Choctaws are descendants of Native Americans who occupied this territory prior to European discovery. They are situated in an area straddling the county line between south Washington County and north Mobile County in a community wedged between the small southwest Alabama towns of Citronelle, Mount Vernon, and McIntosh. They are descendants of Choctaw Indians who remained in this isolated woodland area after most members of their nation traveled west during the Indian removal of the 1830s. The ancestors of the MOWA settled in the area north of Mobile in two phases. The earlier group chose to fight on the side of the Red Sticks-Creek Indians (Muscogees) who carried bright red war clubs-during the Creek War of 1813-14. After the war ended, they fled to the swamps of south Alabama as refugees and outcasts.

The second phase occurred with the onset of Indian removal in 1830, when portions of the main group of south Alabama Choctaws remained in the area rather than moving west; they eventually joined the Creek War refugees, and the descendants of these two remnant Choctaw groups survive today as the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians.

The Choctaws who sided with the Red Sticks had come under the influence of the great Shawnee Indian leader Tecumseh, who traveled south from the Great Lakes just before the start of the War of 1812, seeking to unite all Indians against the Americans. According to writer Sean Michael O’Brien, “at least sixty-five Choctaw warriors and their families from two small towns on the Tombigbee [River] and Yahnubbee Creek” responded to Tecumseh’s plea to unify all southern tribes against the Americans, even though Choctaw chief Pushmataha said that he would “put to the sword” any Choctaws who fought against the Americans. 20 Fearing that Pushmataha would make good his threat, the Choctaws who fought on the side of the Creek Red Sticks retreated to the swamps between the Tombigbee and Alabama Rivers after the conclusion of the Creek War. 21

For generations, elders told stories of this time period, passing on to young people the tribe’s oral heritage. One of the many accounts, consistently repeated in my interviews with MOWA elders, is that of MOWA ancestor Nancy Fisher, “the Indian woman who swam the river with her baby on on her back.” 22

The tale of her heroic escape from Creek Indians after the battle and massacre at Fort Mims of August 30, 1813, has been told through generations of MOWA Choctaws. Traditionally, the Creeks were on the east side of the Tombigbee River and the Choctaws were on the west side. Various written accounts exist of several Fisher families, both Creek and Choctaw, who lived in the area, along with accounts of people fleeing Fort Mims to safety on the Choctaw side of the river. 23 More specifically, an anonymous letter from Fort Stoddert (near Mount Vernon) dated June 15, 1816, and published in a Mississippi newspaper supports the story of Nancy Fisher’s dramatic escape:

Late Tuesday night, about the rise of the moon, five Creek Indians came to the home of Mrs. Fisher, about fifteen miles below this place on the eastern bank of the river. Three of them fired on a Chactaw [sic], who had been at the same time above Fort Montgomery, engaged in hunting and who was then encamped near Mrs. Fisher’s house. As soon as they had killed him, they fired at the door[,] upon which her daughter [i.e., Nancy Fisher] catched up a child[,] escaped at the opposite door, and the Indians rushed in and fell upon [the] old woman with clubs. Her cries only excited the taunts of the Indians, whose conversation, in the Creek language, was heard by her distracted daughter. The old woman was left for dead; but the daughter got to a canoe and escaped, with the child, to the swamp on the western side of the river, where she soon saw the house buried in flames. 24

The facts of this account-the name Fisher, the time it was written, the location on the river, and the identification of the participants-support the MOWA Choctaws’ oral heritage. Although the BIA’s Branch of Acknowledgement and Research (BAR) has discounted the MOWA’s oral history, this written account shows that recollections passed down through generations of MOWA should not be dismissed as unreliable.

For almost two decades the Choctaws lived in their isolated world. President Andrew Jackson made good on his campaign promise to remove all southern Indians to areas west of the Mississippi River, beginning with the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek of 1830. Although article 14 of the treaty provided for a land allotment of 640 acres for each Choctaw head of family who wanted to stay in their homeland, only sixty-nine family heads were even allowed to sign under these provisions. 25 Of these sixty-nine who managed to sign under the terms of article 14, most were mixed-bloods who knew how to function in both Indian and white worlds, and they sold their allotments to white settlers. The others were to be removed in three phases. Promises broken by the government, plus hardships and diseases encountered by the first group that migrated west, discouraged others from making the trek. Most Choctaws were left to fend for themselves, landless in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. 26

As late as 1852 the mayor of Mobile petitioned President Millard Fillmore on behalf of more than four hundred Choctaws still in the city. 27

The petition-also signed by Choctaw leaders Holli ta nau tubee, Hou cha, Ila tam be`, and Me ha-indicated that the Indians had been waiting since 1832 to be shipped west. 28 When the U.S. government failed to live up to its treaty promises of subsistence, transportation, and land in the West, these Choctaws became discouraged and eventually joined the Choctaw refugees who had lived in the nearby swamps since the end of the Creek War of 1813-14. Oral history, birth and death records, and census records confirm that this second group of Choctaws intermarried with the earlier group. 29 The members of this consolidated group of Choctaws struggled to survive on the margins of white society in south Alabama. Many of the women gathered firewood, sold it on the streets of Mobile, and became known as chumpa girls for the Choctaw word they uttered when offering their firewood for sale. 30 The men hunted and sold game and deerskins. 31 The federal government made several failed attempts to move them west until the outbreak of the Civil War, when all removal activity ceased. Thus the Choctaws who lived in Mobile and Washington Counties were never removed. 32 In 2006 about five thousand of their descendants continue to live along the Mobile-Washington county line, territory that was part of the Choctaw homeland prior to European settlement.

These Choctaws have a profile typical for southeastern Indians. Although some non-Indians realize that not all Native Americans were removed when the U.S. Army marched the tribes west, they know little of the fates of those who remained in the Southeast. Indeed, the fragmentation of the Five Civilized Tribes before, during, and after removal makes their history an intriguing story of persistence and survival. Unfortunately, the effects of this fragmentation have served as justification for refusing to recognize the remnant tribes as real Indians. Many of the Native Americans who successfully remained in the East did so by giving up their Indian identities and becoming citizens of their respective states. But hundreds of small groups of Indian peoples from Virginia to the Texas border resisted both removal and assimilation. Many of the smallest communities were simply not in the way of white settlement, living in the mountains and along bays and rivers where the land was unsuitable for growing cotton or sugar-cane on a large scale. These groups had been self-sufficient before the coming of the white man, and many retained their traditional way of life into the twentieth century. Numerous Indian tribes such as the Tunicas, Chitimachas, Houmas, Appalachees, and many bands of Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles simply blended into the environment and fended for themselves. 33 They had not, as a rule, been party to the tedious negotiations with the federal government and saw no reason to be burdened with the stifling bureaucracy that it represented. Ancestors of today’s MOWA Choctaws remained hidden for decades in the swamps and pine barrens just north of Mobile.

Extensive research in U.S. government records shows that the MOWA Choctaws’ credentials are solid, and the historical data that identifies them as Indians extends back to the days when their villages were integral parts of the Choctaw Nation. Their ancestors have been documented in U.S. government records as a distinct American Indian community since shortly after the 1830 Indian Removal Act. Two documented descriptions of the Choctaw refugees of the Creek War, one in 1819 by an agent of the U.S. Navy and one in 1824 by a doctor, confirm their continuing presence in the Mobile area before the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. 34 After this treaty was signed, but not fully implemented, Choctaws came to the Mobile area seeking help. Twenty-eight years of correspondence between local and federal officials, dating from 1832 to 1860, documents the Choctaw’s loss of land, the actions of fraudulent government agents, Indian starvation, and the Choctaws’ desire to remain in south Alabama. 35 The 1852 letter that the mayor of Mobile sent to President Millard Fillmore protested ill treatment by federal agents and was signed with a mark (“X”) “on behalf of all the Indians of South Alabama of the Choctaw Nation.” 36

A government Indian school built in 1835 at Mount Vernon, Alabama, near the U.S. Army’s Mount Vernon Barracks, is further proof of the Choctaws’ presence in the area. The school is documented in the federally sponsored Historic American Buildings Survey as “built for Government School for Indians by Indian labor.” Elders recognize the photograph as the “old Weaver School” and can point out its former location in their community on Mobile County Road 96. 37

These Choctaws essentially became fugitives in their own homeland when the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek took away their lands and turned them into squatters. They joined the Choctaw refugees of the Creek War who had earlier settled in the heavily forested, marginally desirable land along the Tombigbee River. The two groups intermarried and maintained a community separated from the surrounding white population. This segregation was partly due to the amalgamation of the Choctaw families who escaped removal, but it was also the result of an intentional retreat from white society in an effort, only partially successful, to escape persecution. Elders have described to me the suffering of their ancestors, who were hunted down and imprisoned. These stories, passed from generation to generation, include horrifyingly specific accounts of atrocities that include brutal murders and dismemberments, with the remains of victims stuffed in gopher holes. They also tell of forbears who were declared black and enslaved or taken west in periodic “Indian round-ups” by government-paid contractors until the start of the Civil War. Similar events are also well documented in books written about Indian policy during the antebellum period. 38

During the Civil War another type of round-up further decimated the ancestors of the MOWA Choctaws. In 1862 the Confederate secretary of war issued an order to enlist all the Indians east of the Mississippi River as scouts. According to an account by S. G. Spann, who commanded a battalion of mounted Confederate cavalry during the war, the Choctaw men were recruited into service at a camp located “at the foot of Stone Street in Mobile.” With the promise of a fifty-dollar bounty, clothes, arms, camp equipage, furnishing, and Enfield rifles, the Choctaw men enlisted and went off to war. Most were killed, but their families remained. 39

After the Civil War, the Choctaws continued to live in the Mobile area, a hidden community virtually unnoticed until their forest habitat became commercially desirable in the second half of the nineteenth century. Their limited interaction with the other residents of the region was on terms dictated by the Reconstruction era’s stark delineation of race. In fact, the modern concept of the American Indian did not exist in postbellum southern society. For one hundred years after the Civil War, laws governing race in the South were for either whites or blacks. Anyone not identified as “pure white” was governed under civil regulations that applied to blacks; Indian identity was submerged. Renée Ann Cramer, an authority on federal Indian policy, concludes that “as a result of the loss of their Indian identity due to classificatory structures, and the decimation of their tribal structures due to Removal, the remnant groups found it difficult to control their own governance, and faced losing the ability to maintain their public ethnic boundaries.” 40 Consequently, American Indians living in the South became a group of people who officially did not exist. They were made, in effect, extinct by reclassification.

Since 1830, few people other than refugees from other Indian communities in the region have wanted to join what became the MOWA Choctaw community. From an Indian perspective the community was a way to hold onto a valued, traditional way of life while living in a sacred place-their ancestral homeland. It provided refuge when they had nowhere else to go. Local non-Indians, however, considered the Choctaw community, the place where they lived, and the people themselves to be marginal. In fact, over time a social and economic wall-an invisible barrier as impenetrable, as one Choctaw elder said, “as the wall built in Berlin, Germany”-was built around the Indian community. 41 This wall limited where they could live, where they could work, whom they could marry, and what they could become.

It confined them to their forest region of refuge in a manner that persisted until the mid-1880s, when timber companies, having clear-cut the major forests of the North, set their aim on the abundant pine forests of Alabama and neighboring states. The years between 1880 and 1920 were a period of cultural transition for American Indian tribes. The Indian community that would become the MOWA Choctaws experienced this transition in the context of the industrialization of the southern woodlands.

The majority of the south Alabama Indians lived as squatters on public land, part of the original Choctaw territory. Before the Civil War, only whites and free people of color were eligible to purchase land. As Indian families grew in the early years, the first communities developed around the homes of leaders who could pass as non-Indian and thus could buy land. Their children and grandchildren built cabins nearby on public land to which they held no legal title. Some men entered the lumber industry when it was still primarily a local business satisfying local demand, with more trees being cut to clear land for farming than for lumber. The longer logs, used for ship spars, were sold in Mobile. One of the Choctaw elders, Roosevelt Weaver, explained how early families worked together cutting logs and getting them to the market in Mobile:

Before any sawmills come in, old man Isaac Johnston run logs in the river and took rafts to Mobile. Men from different families cut the tall timber. They “snaked” the logs to a creek with a team of oxen and rafted the logs together. When the rains came and the creek rose, they climbed on the raft, steered it with 15-foot paddles to keep it in the main stream and out of the woods. My daddy said they always had a tent stretched on the logs, on the front end. That’s where they cook and eat going to Mobile. The log raft was a whole year’s worth of work and if they lost control of it, there would be no payday. 42

This logging activity was ongoing in the 1880s, when northern lumber companies began looking at timberland in southwest Alabama and discovered the Indian families living there. Desiring to gain legal access to the land, which was still owned by the federal government, lumber company officials enlisted the aid of L. W. McRae, a state senator from Washington County, to clear any Choctaw claim to the land. 43

Senator McRae recognized that the residents were Indians. He also realized that Indians had no rights in Alabama and could not own land, but he wanted to bring industry to the region and use the Indians as the labor force. To facilitate the acquisition of the land, he suggested calling the Indians “Cajuns” because he believed they looked like the descendants of the French-speaking Acadians who resettled in Louisiana. 44 By creating a new identity for the Indians as “Cajuns,” they could be listed on the U.S. census, made to pay taxes, and obtain title to land under the terms of the Homestead Act of 1862. With the promise of jobs in the timber industry, the Indians could then be induced to lease the timber rights to their land holdings for the lumber and naval stores industries.

Having established a new identity for the south Alabama Choctaws, the senator worked with John Everett, a trusted Indian community leader, to help them acquire land through the Homestead Act. 45 Elders tell of horse-drawn wagons and then flatbed trucks loaded with people who were taken to the Washington County seat at St. Stephens, where each one filed homestead papers for 160 acres of land. 46 John Everett learned the timber business quickly. He built a turpentine still, opened a commissary, and hired his Indian relatives as workers. He hired the Indians to work on shares to collect the sap from the pine trees and deliver it to his still. When the processed turpentine was sold at the market in Mobile, the Indians’ share would be used to pay their debts at Everett’s store, where they had charged food and whiskey. When property tax came due, they had no money to pay, so they deeded their land to John Everett. Years later, tribal member Richard Weaver described how the process worked:

John Everett got hold of the land like this. The land wasn’t worth nothing, fifty cents to a dollar an acre was all you paid for it. He kept buying until the first thing he knowed he owned all this country. Old man Everett run a business before he ever got up with the Boykins. Frank Boykin, before he got with John Everett, worked in a store out there at Fairford Lumber Company, a bunch of Englishmen owned all of that land, about 100,000 acres. Everett and Boykin, that’s what they called their business. So, John and Frank bought all the land they could find and got a contract with Taylor Lowenstein to hang it with turpentine cups [tap trees and collect sap] and folks here worked for them. Dick Boykin run the store at Calvert, and if you worked for Boykin and Everett you could go down to that store and get anything you wanted. He [Dick Boykin] talked to the people and filled their orders. They [the Indians] didn’t have a list cause they couldn’t write, you know. But when a fellow got in a tight and couldn’t pay the grocery bill, well they give him a little money and took the homestead deed. They moved the families out of the woods and give them a few acres along Topton Road. I remember a time when John Everett and Frank Boykin both, back in 1922, they was both recognized to be worth $1 million cash apiece, both was a millionaire. They had thirty-five turpentine stills running at one time, all in Baldwin County, Mobile County, and Washington County. When John Everett fell dead in 1929, when the people’s bank went broke, the Boykins just took it all. They let the people live on the land, farm and raise cows. Mr. Frank let them stay as long as they worked for him. In 1933, when all these depression times was, Mr. Frank run for congressman. He was elected and went to Washington, D.C. His brother run the business, Mr. Rob. He worked all of my people in this part of the country. 47

As locals such as McRae, Everett, and Boykin were manipulating the south Alabama Choctaws for their own advantage, the ancestors of the MOWAs also found their lives disrupted by the incursion of northern timber companies into the area. The advent of timbering on an industrial scale brought new opportunities for employment on logging crews, but it also exposed the Choctaws to the outside world and required them to relocate to railheads and other sites in the area that they had traditionally avoided. The clear-cut timbering techniques of the northern companies meant that the creeks and rivers were no longer adequate for transporting lumber to ports, so the companies had to build rail lines and establish adjacent lumbering camps. Locals employed as loggers had little choice but to move to the camps and mingle with the new faces that the timber companies brought to the area to augment the local labor force. Moreover, the arrival of outside timber companies brought an end to traditional selective harvesting practices (clearing for farming and felling selected trees for specialized uses such as masts and spars) in favor of clear-cutting vast tracts of land, which gradually destroyed the forest environment that had supported the Choctaws’ hunting and gathering practices for over a century. 48

Thus by 1930, the lives of the south Alabama Choctaws had been forever changed, and more changes loomed. During the Great Depression, the economic consequences of being a south Alabama Choctaw Indian continued to increase. It was after Everett died and Boykin took over the business that he moved the Choctaw families out of the forest and relocated them to clusters of houses along county roads. Boykin told the Choctaws that they would each be given a deed to forty acres and a house; that they could hunt and plant gardens on their land; that they could work for the company cutting timber or dipping turpentine; and that they could charge provisions at the company store-as long as they worked for him. At the end of the month, their wages usually did not cover what they owed, so they became indebted to the company. To secure the debt, Boykin’s company held their deeds.

One Choctaw elder recently recalled the details of how he became indebted and lost his land: “It was like this. I owed nine dollars at the company store and couldn’t pay it. The bossman had the deed to my forty acres and kept it in his pocket. He would pat his pocket and say, ‘When you pay up, I’ll give you the deed.’ I never did get paid up and I never got my deed. I had to keep working for him though, because I had a family to feed.” 49

This was true of the majority because, if the Indians tried to work for another employer, Boykin told them that he would notify the federal government that they were Indians and have them sent west. 50 He used this threat to acquire land from Indians who would not willingly sign their land over to him. One Indian who was reluctant to sell had the misfortune of trespassing on Boykin’s land, where he shot a doe deer.

Boykin threatened to report him to the federal authorities for illegal hunting unless he let him have the land. 51 This threat exploited a persistent fear by many Choctaws that they would be forcibly removed to Oklahoma by the federal government because their ancestors had been unable or unwilling to avoid removal under the terms of article 14 of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. This tactic of intimidation was effective, of course, because Boykin understood that threats to reveal their presence to authorities would only matter to people who identified themselves as Choctaw Indians and believed that the prospect of removal still loomed.

By the 1920s, when the major forests were cut over, the lumber companies moved on. The Great Depression was at hand, which affected everyone. Choctaw elders referred to these years as the “starving time.” Their land was gone, their Choctaw identity was obscured, and their forest refuge was destroyed. Without the cover of the forest, game animals, which were a major source of food, became scarce. Choctaws were without work, living on small plots of cutover land and at the edge of white communities, whose citizens scorned them. This ostracism continues today, to some extent. Local white skeptics question how much Indian blood they really have. 52

Although these Choctaws lost their land, were denied their identity, received little formal education, and were kept in debt peonage, there is nevertheless documentary evidence of their continuous history in the area. Documentation abounds in land records, missionary records, census records, birth and death certificates, sworn court testimony, government correspondence, military records, medical studies, anthropological descriptions, and the correspondence of Congressman Frank Boykin. An excerpt from a recently discovered letter he wrote to one of his colleagues in 1960 confirms their presence:

We have a lot of wild Indians . . . here. Well, we sent them . . . to Oklahoma, after having them in captivity here a long time. Well, I still have a lot of them and they work for us. They can see in the dark and they can trail a wounded deer better than some of our trail dogs. 53

Thus Boykin describes the Choctaws as descendants of Indians who escaped removal and remained in the area that they currently inhabit. Although Boykin’s use of the term “wild Indians” is insulting, it is, nevertheless, an indisputable description of them as an Indian community.

The strongest evidence of the MOWA Choctaws’ Indian ancestry is not, however, found in written documents; it is found in their lives. Their ancestors passed to them their Choctaw Indian identity and traditions, persevering and preserving their heritage despite a long history of persecution and discrimination. Interviews with elders reveal stories of survival by hunting, fishing, trapping, and sharing the kill; rituals related to marriage, birth, and death; customs associated with gardening, medicinal plants, logging, dipping turpentine, and restricted communication with outsiders; and ancestral relationships told generation to generation. 54

Despite hardships, the Choctaw Indian community north of Mobile persisted as a system of social relationships solidified within ceremonial gathering areas, churches, schools, cemeteries, and kin-based villages. Reduced in numbers, and increasingly a dominated minority in their own homeland, the ancestors of the MOWA Choctaws made new alliances. The most important of these were with Protestant missionaries, who did not seek land or power; they wanted converts. These missionaries sought to educate and prepare lay preachers among the Indians, and from that time until today, MOWA community leaders often have been mission-educated ministers. 55

In the 1920s, the Alabama Baptists began a mission ministry in Washington County among “American Indians of Choctaw heritage, under the overall program of missions to American Indians.” 56 In the 1930s, Methodist mission work with “Indian Cajuns” began in Mobile County. 57

Missionary teachers taught school in Indian churches and boarded in the homes of tribal members. The desire for learning was strong among the Indian people; uneducated as a result of segregation laws, they knew that education provided a means of dealing with affairs in the non-Indian world. Eventually, after the missionaries appealed to school superintendents in Mobile and Washington counties, the Indian schools began receiving limited state and county assistance, which marked the beginning of a separate school system for Indians in Mobile and Washington counties. Thus the two counties maintained three school systems-one for whites, another for African Americans, and a third for Indians. This arrangement persisted until the 1960s, when the campaigns of the civil rights movement ultimately brought an end to Alabama’s system of segregated public schools. 58 Because their schools were not accredited, Indian children had to leave the state to get a high school education. As early as the 1950s, some went to preparatory school at Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma, at a time when only Indian students were allowed to enroll. 59 Some of these students went on to college and returned home to teach in their schools and preach in their churches. They became leaders in the Indian community and arranged for young people to attend the Mississippi Choctaw Reservation’s Choctaw Central High School, a tribal school for American Indian students.

College-educated Choctaws, many returning with master’s and doctoral degrees, have assumed leadership positions and have made a huge impact on their community. As one teacher said, “This was important because the Indian pupils had some of their own people with whom to identify. The parents had someone now whom they could trust to read and write for them. Now we had people who could organize plans to implement goals for our people, one of which was to vote.” 60

The enactment of civil rights laws in the 1960s represented a turning point for the MOWA Choctaws; they could avail themselves of significant opportunities not available to previous generations, who were classified as non-white and therefore subject to Jim Crow laws. Several reporters who wrote about the Choctaws in earlier periods speculated that if the color bar were ever dropped, the Choctaw Indians’ identity, and indeed the community itself, would soon disappear. 61

These predictions could not have been more wrong. With racial discrimination outlawed, expressions of Indian identity among the Choctaws intensified rather than declined. Public resurgence of the Choctaws’ identity can be understood when compared to George Pierre Castile’s analysis of the expansion and contraction of ethnicity in Persistent Peoples: Cultural Enclaves in Perspective: “While persecution can serve to reduce membership temporarily, it also serves, as many have noted, to increase the strength of the identification of the post-persecution membership. As long as a minimal, ‘adequate’ mechanism survives, suitable for the transmittal of the symbol sets to new members, the enclave persists-although many of its members may not.” 62

Indian schools are one example of this phenomenon. Leaders of the local Choctaw community prevented an attempt in 1970 to close all Indian schools in Mobile and Washington counties because of the Indian majority in the schools. 63 Determined to save their schools, the MOWAs worked together to gain political strength and influence. They obtained a federal court order mandating that one Indian school in each county remain in operation.

Evidence that education was the key to throwing off the scourge of discrimination can be found in the federally funded Indian education programs in the public schools in both Washington and Mobile counties. 64 In 2005, Calcedeaver Elementary School ranked third out of the 778 elementary schools in the state in the Alabama Reading Initiative, with 97 percent of the students reading at or above grade level. 65

In the past, members of the Choctaw community who wanted a college education had no choice but to go out of state, and today some young Choctaws still choose to attend American Indian colleges in other parts of the country. Increasingly, however, more Choctaw students are attending colleges and universities in Alabama and are attaining enviable records of achievement. One such student, Heather Wilkerson, graduated from the University of Mobile in 2004. She finished in three years with a 4.0 grade point average. Wilkerson was described in the Mobile Register as “UM’s ‘perfect’ graduate.” 66

Although the Alabama Choctaws managed to keep their schools, their economic situation did not improve. The arrival of chemical plants in the 1950s did not bring employment to local Choctaws. In the late 1960s tribal leaders contacted the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, established in 1965, which led to negotiations with the industries in the area regarding employment for Indians. 67 Although a few got jobs at the chemical companies, most worked with their extended families planting pine seedlings for the local timber company. Extended families also obtained income by participating in seasonal migrant farm work. For the majority, living conditions did not improve. 68

During the 1970s the Choctaws did receive a limited federal concession of their existence. Of particular importance was a report by the American Indian Policy Review Commission (AIPRC), which described the four thousand Choctaws in Mobile and Washington counties as a “non-recognized tribe.” 69 Congress had created the AIPRC in 1975 to examine the historical and legal background of federal-Indian relations and to determine if policies and programs should be revised. The commission found that the results of non-recognition were devastating for Indian communities, leading frequently to total loss of land and deterioration of cohesive, effective tribal governments and social organizations. Non-recognized Indians, the AIPRC concluded, represent a sort of underclass within an underclass. In comparison with members of recognized tribes, they tend to be poorer, less educated, and prone to greater health problems. Most are landless, or have been reduced to extremely small tribal holdings. The AIRPC report notes that at the local level tribes that are not recognized by the federal government frequently comprise caste-like groups simply because they are not white. This status generally confers recognition of a negative sort, especially in the South. Most tellingly, the commission charged that budgetary considerations, not the framework of the law, had frequently determined federal Indian policy. The commission recommended the creation of federal regulations establishing criteria for conferring recognition on non-recognized Indian groups. 70

The new Federal regulations created as a result of the AIRPC’s recommendations provided local Choctaw community leaders with a long-awaited opportunity to formally re-establish their identity.

Recognized tribes, fearing the possibility of reductions in their federal funding, wanted to tighten the definition of the word Indian and succeeded in obtaining a regulatory provision requiring state recognition as a precondition to federal recognition. 71 Therefore, before they could apply for federal recognition as an Indian tribe, the south Alabama Choctaws would have to secure recognition from the state. 72 In 1979 the Choctaw leaders obtained the support of their representative in the state legislature, J. E. Turner, who secured the passage of legislation that created a commission to support the needs and interests of Native Americans in Mobile and Washington counties. Despite the cumbersome official name of the body-“the Mowah Band of the Choctaw Indian Commission”-the fourteen-member commission was empowered “to deal fairly and effectively with Indian affairs [and] to bring local, state and federal resources into focus for the implementation of meaningful programs for Indian citizens” in the two counties. This legislation became the basis for state recognition of the MOWA Choctaws. 73

After the state of Alabama formally recognized the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians as an Indian tribe, it became eligible for the services in education, healthcare, housing, childcare, and eldercare that the federal government provides for American Indians. 74

To facilitate these programs and others, the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission (AIAC) was created in 1984. AIAC acts in a liaison/advocacy role between the various departments of governments and the Indian people of the nine state-recognized tribes and represents more than 38,000 American Indian families who are residents of the state of Alabama. 75

The MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians opened its first tribal office in 1980 and began the process of seeking federal recognition from the BIA. MOWA Choctaws are, and have always been, a self-governing community following the traditional habits of their ancestors rather than the rigid institutional organization that the federal government requires of recognized Indian tribes. They believe that traditional ways are more straightforward and enable the community to meet the needs of its members, whereas the institutional process serves only people who fit into rigidly defined categories of assistance. Thus their political and social profile does not always fit into the neat and narrow categories required by the federal recognition process. The refusal of the BIA’s Bureau of Acknowledgment and Research (BAR) to credit oral history, and its determination to have a comprehensive, documented account of tribal life, distorts the history of petitioning groups, making a tribe unrecognizable to both its own members and to other Native Americans. Specifically, critics charge that the BAR’s criteria for federal recognition conform to white society’s ideas of the characteristics that impart lawful form to an Indian tribe. Consequently, obtaining federal recognition requires a tribe to abandon or modify its traditional pattern of social organization in favor of an alien pattern, thereby changing their social reality to legal fiction. 76 American Indians are the only people in this country who have to prove to the United States government that they are who they say they are.

Although the Alabama legislature officially recognized the MOWA Choctaws as a tribe in 1979, as did the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs in 1991, the Bureau of Indian Affairs denied their federal acknowledgment petition (FAP) in 1997. As MOWA chief Wilford “Longhair” Taylor observed in his testimony before the House Committee on Resources in March 2004, “The Federal recognition process was designed to take two years, but in reality the process often places a petitioning group in an endless ‘loop’ of research and expense that, for most tribes, is overwhelming.” 77 Chief Taylor noted that seven years passed before the MOWA Choctaws’ initial petition was processed in 1991, and ten more years went by before the final determination report was completed. If the years needed to undertake the research the BIA requires for documentation are included, the average time for a tribe to complete the process is more than twenty years, at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars. 78

The ultimate irony for the MOWA Choctaws is that the isolation, discrimination, and persecution that forged the bonds of their common identity continue to impede their ability to obtain official recognition as an Indian community. The BAR denied their petition for federal recognition primarily because of insufficient written documentation by outsiders substantiating the reality of their history and their lives. 79 Recent articles by scholars on this subject contend that the issues of gaming and race are pivotal factors in determining whether a non-recognized tribe receives federal recognition. 80 In her review of Mark Edwin Miller’s book Forgotten Tribes: Unrecognized Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process (Lincoln, Neb., 2004), Sara-Larus Tolley notes that Miller “argues that the BAR has made several confused rulings because of racial ancestry biases; and he stresses that gaming has worked to ‘retard refor[mation] of the FAP.'” 81 Renée Ann Cramer concurs: “Certainly, gaming success has resulted in a threat to tribal acknowledgment claims. Across the nation, gaming has provided resources and power for some recently recognized tribes, while casting shadows on the legitimacy of other petitioning groups. . . . [R]esources generated by the gaming tribes can be effectively used to help or hinder the efforts of unrecognized groups in the region.” 82 The latter has been true for the MOWA Choctaws. Leaders of the Alabama Poarch Creeks and the Mississippi Choctaws, both of whom are federally recognized and operate casinos, oppose federal recognition of the MOWA Choctaws. 83

At this juncture, it is important to make the point that the MOWA Choctaws did provide the BAR with substantial documentation of the type that is acceptable to the bureau in these matters. The clear evidence provided to the federal agency should have been more than sufficient to meet BAR standards and obtain federal recognition for the MOWA Choctaws.

In brief, the BAR accepts that Indians remained in the area inhabited by the MOWA Choctaws today after the 1830 Indian Removal Act. It also accepts that the MOWA Choctaw community demonstrates a clear lineage from late-nineteenth-century core ancestors with Indian traditions.

The crux of the denial is that the MOWA ancestors who lived as a separate community in the mid- to late nineteenth century cannot be documented according to BAR guidelines through records produced by the non-Indian people who persecuted them. By denying the petition, the BAR is, in effect, saying that the MOWA Choctaws are non-Indians. But it defies reason that a group of non-Indians in the second half of the nineteenth century would voluntarily adopt Indian traditions that would only invite persecution. Even if such self-destructive individuals existed, then it would mean that another unidentified Indian group in the MOWA Choctaw area taught these non-Indians their foreign traditions.

Such a scenario is as far-fetched and irrational as the BAR’s decision to base its final, negative determination on only one criterion-genealogy. The BAR requirements state that if a tribe cannot prove by U.S. government-generated documents that its members descend from more than one ancestor who was a member of a historic tribe, the BAR then issues a negative determination without addressing the other six criteria. 84 The MOWA Choctaw ancestors had Indian traditions because they were Indian.

It is disappointing that the BAR, part of a federal Indian agency, places so little value on oral traditions, the means by which American Indians and other non-literate peoples have passed their history to the next generation. Disregarding these traditions demonstrates disrespect for their venerated elders and more generally, disrespect for Indian cultural traditions. Moreover, the persistence of the MOWAs oral history, passed down through generations to multiple descendants, could only have been motivated by a desire to preserve their heritage. Tribal member Cedric Sunray-a graduate of Haskell Institute and the University of Kansas, where he earned an advanced degree in American Indian languages-put it well in a presentation to the MOWA Tribal Council:

When elder after elder recounts the same story in a relatively similar fashion . . . how can we discount it? How could an entire group of elderly people be convinced to lie and falsify such a long story? They would need to go against their own collective beliefs, have meetings to get their stories “on the same page” and then, with a straight face, lie to anthropologists and BAR officials. No one could possibly believe that the senior population of the MOWA community organized to this level with the intent to mislead the BAR. 85

Having rejected the validity of MOWA oral history, the BAR also allowed racial bias to guide its dismissal of the written documentation provided with the MOWA petition. The 1910 U.S. census for Washington County, for example, contains marginal notes that document the Indian identity of local Choctaw families. The census enumerator, a local white citizen named J. B. Cater, initially identified several residents of the Fairford precinct as “In[dian]” but subsequently changed their racial designation to “mixed.” Cater’s marginal notes explain his use of the term mixed, but they also emphasize the Indian ethnicity of his neighbors: “These people entered as mixed are composed of Indian, of Spanish, some of them French, some with White, and some with Negro. The prevailing habits are Indian. Called ‘Cajun.'” 86

Between 1917 and 1918, ancestors of the MOWA Choctaws registered for the World War I draft in Mobile and Washington Counties, and the draft registration cards identify them as “Indian,” “Indian Citizen,” or of “Indian decent” [sic] depending on the version of the registration form used. 87 The 1920 census identified ancestors of the MOWA Choctaws as “French and Indian.” Birth and death certificates from around this time period also identified them as Indian. 88 Moreover, the U.S. census for 2000 is unequivocal in its description of them as Indian. In its race code list, the Census Bureau assigned code C12 to the “Mowa Band of Choctaws” under the category “American Indian and Alaska Native,” subcategory “Choctaw.” 89 The BAR should accept the contemporary classification by the United States federal government of the MOWA Choctaws as American Indian.

The MOWA Choctaws’ experience with the BAR has made it clear that the federal recognition process is rife with politics and bias. Former Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Kevin Gover, who signed off on the negative determination of MOWA Choctaws’ petition, perhaps states it better than anyone can. He is quoted in Connecticut’s Hartford Advocate as saying, “The tribal recognition process should be ‘fair, open, objective, and neutral. . . . [O]ur present system lacks these features and we need an impartial commission.’ . . . Today the tribal recognition process is ‘dehumanizing’ and ‘insulting.’ . . . [I]magine having to prove to the government who you are.” 90

The issue of federal acknowledgment is thoroughly discussed by Renée Ann Cramer, who compares the experiences of Indians in two geographic regions-the Deep South and the Northeast-and specifically, Alabama and Connecticut. She notes that Alabama has seven state-recognized tribes, but only the Poarch Band of Creeks has received federal recognition. The other six have sought federal recognition, “but none so aggressively as the MOWA Choctaw.” 91

The MOWAs, however, are still waiting. In the summer of 2005, they learned that they no longer have any other recourse with the BIA/BAR process. Their only hope for federal recognition is with the U.S. Congress or through litigation. A step toward recognition through congressional acknowledgement was taken on July 28, 2005, when Jo Bonner, congressman from the Alabama first district, introduced a bill titled the Mowa Band of Choctaw Indians Recognition Act. 92

Congressman Bonner’s bill was referred to the House Committee on Resources, where it remains as of July 2006. Ultimate approval of the proposal will prove difficult because of a variety of factors such as heavy demands on the federal acknowledgement process from the many southeastern tribes seeking recognition, charges of corruption at the BIA, scandals involving tribal lobbyists, and elimination of blood quantum requirements for some federal tribes (which creates larger tribal populations and places greater financial burdens on the BIA). Moreover, federally recognized tribes who operate profitable casinos in the vicinity of south Alabama-the Mississippi Choctaws and Poarch Creek-continue to oppose federal recognition of the MOWA, fearing that their gambling revenue might suffer should the MOWAs open their own casinos. Against such odds, the MOWA Choctaws’ quest to secure federal recognition seems like a long shot at best. Yet they persist in their efforts, convinced that federal recognition offers the best hope for improving the lives of tribal members, roughly 80 percent of whom live in poverty. 93

The MOWA Choctaws contend that the BAR does not objectively evaluate tribal petitions, because, in the words of researcher Sara-Larus Tolley, “the process (and the definition of tribe being applied) is fundamentally flawed.” 94 Nevertheless, Chief Taylor continues to aggressively seek federal recognition for his people. He draws inspiration from a 1991 statement made by his late father, Leon Taylor, a revered elder, to the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs: “Today, I am Choctaw. My mother was Choctaw. My Grandfather was Choctaw. Tomorrow, I will still be Choctaw.” 95

Carl Carmer never received a satisfying answer to his question “What’s . . . the origin of these people?” I offer this essay as my Chata Imissa-my Choctaw offering. It is my answer to Carmer’s question.

Copyright 2006 Alabama Historical Association. Used by permission. May not be copied for distribution without permission of copyright holder.

Citations:

- Carl Carmer, Stars Fell on Alabama (New York, 1934), xiv.[↩]

- Ibid., 258. Most Choctaw creation stories say the Choctaw people emerged from a hole in Nanih Waiya, a large mound in Winston County, Mississippi; see Jesse O. McKee and Jon A. Schlenker, The Choctaws: Cultural Evolution of a Native American Tribe (Jackson, 1980), 5-12.[↩]

- Laura Frances Murphy, “Among the Cajans of Alabama,” Missionary Voice, November 1930, 22; Laura Frances Murphy, “Mobile County Cajans,” Alabama Historical Quarterly 1 (Spring 1930): 76–86; Laura Frances Murphy, “The Cajans at Home,” Alabama Historical Quarterly 2 (Winter 1940): 416–27; Laura Frances Murphy, “The Cajans of Mobile County, Alabama” (master’s thesis, Scarritt College, 1935); Horace Mann Bond, “Two Racial Islands in Alabama,” American Journal of Sociology 36 (January 1931): 552–67; R. Clay Bailey, “The Strange Case of the Cajuns,” Alabama School Journal 48 (April 1931): 8; Clatis Green, “Some Factors Influencing Cajun Education in Washington County, Alabama,” (master’s thesis, University of Alabama, 1941); Edward T. Price Jr., “Mixed-Blood Populations of Eastern United States as to Origins, Localizations, and Persistence” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1950); Bibb Bowles Huffstutler, “Oral Anomalies in School Children of an American Triracial Isolate: A Frequency Study” (master’s thesis, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1965); Richard Severo, “The Lost Tribe of Alabama,” Scanlan’s Monthly, March 1970, 81–88; B. Eugene Griessman, “The American Isolates,” American Anthropologist n.s. 74 (June 1972): 693–94; B. Eugene Griessman and Curtis T. Henson Jr., “The History and Social Topography of an Ethnic Island in Alabama” (paper, annual meeting of the Southern Sociological Society, Atlanta, Georgia, 1974), copy in possession of author; Gary Minton and B. Eugene Griessman, “The Formation and Development of an Ethnic Group: The ‘Cajans’ of Alabama” (paper, annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Mexico City, November 19, 1974), available though the Education Resources Information Center, ERIC No. ED133119; George Harry Stopp Jr., “The Impact of the 1964 Civil Rights Act on an Isolated ‘Tri-Racial’ Group” (master’s thesis, University of Alabama, 1971); Calvin L. Beale, “An Overview of the Phenomenon of Mixed Racial Isolates in the United States,” American Anthropologist 74 (June 1972): 704–10.[↩]

- Virginia Easley DeMarce, “‘Verry Slitly Mixt’: Tri-Racial Isolate Families of the Upper South—A Genealogical Study,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 80 (March 1992): 5–35. According to field notes in my possession, provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), DeMarce was the BIA genealogist who in 1987 discredited the MOWA Choctaws’ petition for federal acknowledgment.[↩]

- William Harlen Gilbert, “Surviving Indian Groups of the Eastern United States,” Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for 1948 (Washington, D.C., 1949), 407-38.[↩]

- Jacqueline A. Matte, The History of Washington County: First County in Alabama (Chatom, Ala., 1982), 124-29.[↩]

- The regulations took effect October 2, 1978; see “Procedures for Establishing that an American Indian Group Exists as an Indian Tribe,” Federal Register 43, no. 172 (September 5, 1978): 3961-64. The regulations outlined seven mandatory criteria for acknowledgement; see ibid., 3963. The seven criteria have been revised somewhat over the years but remain essentially the same as those that appeared in 1978. For the current version, consult “Procedures for Establishing that an American Indian Group Exists as an Indian Tribe,” Code of Federal Regulations, title 25, sec. 83.7 (April 1, 2005). The Code of Federal Regulations is available online at http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/ECFR?page=browse.[↩]

- House of Representatives, Additional Land and Indian Schools in Mississippi . . . Report of John T. Reeves . . . , 64th Cong., 2d sess., 1916, H. Doc. 1464, p. 25. See also Jacqueline Anderson Matte, They Say the Wind is Red: The Alabama Choctaw; Lost in Their Own Land, new ed. (Montgomery, 2002), 125.[↩]

- For the 1830 Choctaw census, known as the Armstrong Roll, see American State Papers, 8, Public Lands 7:1-139. Known commonly as the Cooper Roll, the census of 1855-56 can be found at “Six Towns Clan, Jasper and Newton Counties, Miss. and Mobile, Ala.,” Entry No. 260; “Choctaw Roll of Choctaw Families, residing East of the Mississippi river and in the States of Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama, made by Douglas H. Cooper, U.S. Agent for Choctaw, in conformity with Order of Commissioner of Indian Affairs, dated May the 23rd, 1855”; Choctaw Removal Records (microcopy), 1 reel, A40; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C. It is also available online through the USGenWeb Census Project at https://accessgenealogy.com/native/cooper/index.htm (hereafter cited as Cooper Roll).[↩]

- Cooper Roll.[↩]

- “The Choctaw Nation of Indians vs. the United States”: Evidence for Claimant in the United States Court of Claims, Dec. Term, A.D. 1881 (Washington, D.C., [1882?]), 815-17, 828. I first consulted these records in the early 1980s at the General Land Office, Suitland, Maryland, but I saw only the first of two volumes. I subsequently discovered that the Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City, holds volumes one and two. This case was decided in 1886; see 22 Ct. Cl. 489, decided December 15, 1886.[↩]

- Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 81-83. Tribal member Sancer Byrd, drawing on stories he learned from his forebears, recalls that Indians, like blacks, “didn’t have no names. Back yonder Indians had to take the name of the white man.” Ibid, 82.[↩]

- Renée Ann Cramer, Cash, Color, and Colonialism: The Politics of Tribal Acknowledgment (Norman, Okla., 2005), 116. My research using oral history, census records, and Dawes Roll applications supports this conclusion.[↩]

- Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 53.[↩]

- Ibid., 10.[↩]

- Cramer provides several examples of anti-Indian rhetoric: “In the state of Washington, the Republican Party adopted a year-2000 platform that originally contained provisions calling for the military occupation of Indian lands and forced assimilation and removal authorizing of reservation inhabitants. . . . A 1999 paid advertisement in a South Dakota newspaper declared ‘open season’ on Indians in the state, urging hunters to ‘thin out’ the Indian population, or, as the writer put it, ‘worthless Red Bastards, Dog Eaters, Gut Eaters, Prairie Niggers, and F_____ Indians.’ While advocating the use of ‘bloodthirsty, rabid hunting dogs,’ the advertisement recommended finding Indians in bars and liquor stores (caution is urged, since ‘bullets may ricochet and hit civilized white people’), in lines for welfare services and government food distribution, and in city alleys littered with ‘trails of empty wine bottles,’ ‘disposable diapers,’ and ’empty books of food stamps.'” See Cramer, Cash, Color, and Colonialism, 57.[↩]

- “MOWA Chief Slams Lawmakers’ Belittling Remarks,” Mobile Register, March 18, 1997.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 154.[↩]

- Sean Michael O’Brien, In Bitterness and in Tears: Andrew Jackson’s Destruction of the Creeks and Seminoles (Westport, Conn., 2003), 55; Gideon Lincecum, “Life of Apushimataha,” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society 9 (1906): 479. Lincecum’s narrative is supported by references to “disaffected Choctaws” found in correspondence and other documents from the Creek War era. See John Pitchlynn to Willie Blount, September 18, 1813; George Smith to Andrew Jackson, November 23, 1813; John McKee to Jackson, January 6, 1813 [i.e., 1814]; and McKee to Jackson, January 26, 1814; all in Andrew Jackson Papers, 78 microfilm reels (Washington, D.C., 1961), reels 6-8. See also “Narrative, December 5, 1813,” John McKee Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; David Holmes to Turner Brashears, August 3, 1813, Executive Journals, 1798-1817 (Series 491, available on microfilm, MF 5125), Mississippi Territorial Governor’s Papers (formerly Record Group 2), Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; and John McKee to G. S. Gaines, January 2, 1814, Records of the Fifth Auditor, box 1, account 475, Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group 217, NARA.[↩]

- O’Brien notes that “Descendants of these rebel Choctaws-known today as the MOWA Choctaw-still live in the marshlands north of Mobile where the warriors and their families retreated after the conclusion of the Creek War”; In Bitterness and in Tears, 55-56.[↩]

- Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 35.[↩]

- H. S. Halbert and T. H. Ball, The Creek War of 1813 and 1814, ed. Frank L. Owsley Jr. (1895; repr., Tuscaloosa, Ala., 1969), 143-76; Albert James Pickett, History of Alabama and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period (1851; repr., Birmingham, 1962), 528-49.[↩]

- Washington Republican and Natchez Intelligencer, July 10, 1816.[↩]

- Andrew Jackson to John Coffee and John H. Eaton, August 27, 1830, with enclosure, Andrew Jackson to “Friends & Brothers of the Choctaw Nation,” August 26, 1830; folder, Choctaw 1830; Miscellaneous Choctaw Records, 1825-58; Records Relating to Indian Removal; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs; Record Group 75; NARA. “Choctaw Nation of Indians vs. the United States.” Anthony Winston Dillard, “The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek between the United States and the Choctaw Indians in 1830,” Transactions of the Alabama Historical Society 3 (1898-99): 99-106.[↩]

- William Armstrong to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, April 27, 1847; Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1881 (microcopy), frames 226-27, reel 188, M234A; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75; NARA (hereafter cited as M234A, Letters Received by OIA). According to historian Daniel Usner, some “Choctaws never left the Lower Mississippi Valley at all, with several communities remaining scattered in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama”; Daniel H. Usner Jr., American Indians in the Lower Mississippi Valley: Social and Economic Histories (Lincoln, Neb., 1998), 116.[↩]

- “Petition in behalf of all the Indians of South Alabama of the Choctaw Nation to Hon. Milliard Fillmore, President of the United States,” August 17, 1852, frames 42-47, reel 172, M234A, Letters Received by OIA.[↩]

- George S. Gaines to Gen. Geo. Gibson, June 30, 1832; Entry 201, Letters Received, 1831-36; Records of the Commissary General of Subsistence, 1830-37; Records Relating to Indian Removal, 1817-86; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75, NARA. “Committee Report,” February 1, 1832, General Files (Series 1), box 1, envelope 4, folder 1, document 29 in Records of the Mayor and Board of Aldermen (Record Group 2), Mobile Municipal Archives, Mobile, Alabama.[↩]

- Washington County Birth Records, 1920-41, Washington County Death Records, 1920-40, Records of Washington County, Alabama Department of Archives and History (ADAH), Montgomery. For cemetery records, see Robert P. Stockton and Barbara Waddell, The History of Washington County: First County in Alabama; Volume II (Easley, S.C., 1989).[↩]

- Chumpa has two meanings, “sweet” and “offer to sell”; see Cyrus Byington, A Dictionary of the Choctaw Language, ed. John R. Swanton and Henry S. Halbert (Washington, D.C., 1915).[↩]

- Charles Lanman, Adventures in the Wilds of the United States and British American Provinces (Philadelphia, 1856), 2:190-97; James Stuart, Three Years in North America (New York, 1833), 2:122-23; Gordon Baylor Cleveland, “Social Conditions in Alabama as seen by Travelers, 1840-1850: Part 1,” Alabama Review 2 (January, 1949): 13-16; Caldwell Delaney, The Story of Mobile (Mobile, 1953), 77-78; Frederika Bremer, The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America, 1849-1851 (New York, 1853), 1:11. Copies of sketches depicting Choctaws in Mobile in 1851 are in the “Indians” vertical file, Local History Division, Mobile Public Library. The 1850 painting Choctaw Belle by portrait artist Phillip Romer provides striking visual evidence of a Choctaw presence in Mobile before the Civil War. For an image of the painting and a description of Romer’s work, see E. Bryding Adams, ed., Made in Alabama: A State Legacy (Birmingham, Ala., 1995), 157-58.[↩]

- James M. Glenn, “Choctaw Indians Still Make Homes in South Alabama Counties: Familiar Figures in Small Towns,” Birmingham News, May 15, 1927; H. Austill, “White Man’s Friend: Choctaw Chief Pushmataha, a Native Great Man,” Mobile Daily Register, August 21, 1897; Frances Beverly, “The Red Man in Mobile History,” typescript prepared under the auspices of the Federal Writers Project, ca. 1935, “Cajuns” vertical file, Local History Division, Mobile Public Library.[↩]

- Tony Horwitz, “Apalachee Tribe, Missing for Centuries, Comes Out of Hiding,” Wall Street Journal, March 9, 2005.[↩]

- “James Leander Cathcart Journal,” in Jean Strickland and Patricia N. Edwards, comps., Residents of the Southeastern Mississippi Territory, bk. 4, Three Journals (Moss Point, Miss., 1996), 48-49; Lincecum, “Life of Apushimataha,” 479.[↩]

- George S. Gaines to Hon. T. Hartley Crawford, September 22, 1844, reel 1, frames 903-08; William Armstrong to T. Hartley Crawford, November 9, 1845, reel 185, frame 1088; William Armstrong to W. Medill, November 26, 1845, reel 185, frames 1094-95; “One Hundred Red Men” to George S. Gaines, December 6, 1849, reel 171, frames 642-48; James Y. Blocker to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, November 11, 1851, reel 171, frames 741-43; J[ohn] Bragg to Luke Lea, December 29, 1851, reel 171, frames 755-64; William Fisher, to Col. P[hilip] Phillips, January 20, 1854, reel 187, frames 605-06; Douglas H. Cooper to George W. Manypenny, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, May 3, 1856, reel 174, frame 333; Charles E. Mix, Acting Commissioner to William Barksdale, September 3, 1860, reel 176, frames 13-17, 165-66; all in M234A, Letters Received by OIA. The manuscript of the Cooper Roll (cited above at note 9), documents that Choctaws were in Mobile in the 1850s, but the reference to Mobile was dropped from the typed version of the Cooper Roll, “Census of Eastern Choctaws Prepared by Douglas H. Cooper, 1856,” in the records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75, at the National Archives.[↩]

- “Petition in behalf of all the Indians of South Alabama of the Choctaw Nation to Hon. Milliard Fillmore, President of the United States,” August 17, 1852, frame 42-47, reel 172, M234A, Letters Received by OIA.[↩]

- The records of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) at the Library of Congress contain three images of the school by photographer E. W. Russell, March 19 and April 23, 1935; see survey number HABS AL-125, “Indian Schoolhouse, County Road 96 (Old Saint Stephens Road), Mount Vernon, Mobile County, AL,” photograph numbers ALA 49-MOUV 4-1, 4-2, and 4-3, Historic American Buildings Survey Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. The HABS photographs are available online at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/habs_haer/. The Indian school documented at Mount Vernon by HABS is the forerunner of present-day Calcedeaver Elementary School; the name Calcedeaver was adopted when three Indian schools were consolidated into one: Calvert, Cedar Creek, and Weaver.[↩]

- Angie Debo, The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic (1934; repr., Norman, Okla., 1972), 24 -57; Grant Foreman, Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians (1932; repr., Norman, Okla., 1982), 19-104; R. A. Lafferty, Okla Hannali (Garden City, N.Y., 1972), 28; Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 57-63.[↩]

- S. G. Spann, “Choctaw Indians as Confederate Soldiers,” Confederate Veteran 8 (1905): 560-61.[↩]

- Cramer, Cash, Color, and Colonialism, 117.[↩]

- Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 70.[↩]

- Roosevelt Weaver, interview by author, McIntosh, Alabama, July 2, 1986.[↩]

- Matte, History of Washington County, 437. McRae served as a state senator from Washington County from 1892 to 1895.[↩]

- McRae’s role in the creation of the “Cajun” identity was documented in a 1950 dissertation by Edward Thomas Price Jr.: “The name Cajan is almost certainly picked up from the Louisiana corruption of ‘Acadian,’ namely ‘Cajun.’ The difference in spelling is only a matter of practice on the part of those who have put the name in writing. (Some insist on the term ‘Cajan nigger,’ and a few diehards refuse to recognize any position or blood beyond that accorded the negro.) According to local tradition the first to apply the name to the Alabama people was State Senator L. W. McRae, who wished to dignify this strange group of his constituents with a name, which had been previously lacking. . . . Supposedly he found some resemblance to the more famous Louisiana Cajuns. This story was confirmed by Senator McRae’s son, Malcolm McRae, who dated the act as about 1885. The term is regularly used at the present, though displeasing to its objects.” See Price, “Mixed-Blood Populations of Eastern United States,” 54-55.[↩]

- Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 93. John Everett owned a store across from Charity Chapel Church. He and his half-brother, W. H. Ryan (children of Florentine Reed, the daughter of Eliza Reed and Francis Pargado), also operated a sawmill and a turpentine still.[↩]

- “Appendix C-MOWA Homesteads,” Ibid., 185-87.[↩]

- Richard Weaver, interview by author, Mount Vernon, Alabama, August 18, 1983.[↩]

- Matte, The Say the Wind is Red, 53.[↩]

- Lewis Simpson, interview by author, McIntosh, Alabama, April 16, 2004.[↩]

- Roosevelt Weaver, McIntosh, Alabama, interview by author, July 2, 1986.[↩]

- See Tensaw Land and Timber Company, Inc. v. Bessie Rivers, et al. in the Circuit Court of Mobile County, in Equity No. 13685; decided on appeal, Tensaw Land and Timber Company v. Rivers, 244 Ala. 657 (Ala. Sup. Ct., 1943).[↩]

- “Of Turpentine, Timber and Chemical Plants,” Mobile Register, December 18, 2001.[↩]

- Frank Boykin to Sam McGee, August 14, 1960, copy in possession of author.[↩]

- Matte, They Say the Wind is Red, 12. Elders were interviewed by author, 1983-86.[↩]